A spectre is haunting the 20th century - the spectre of comics. It was probably not the most popular media of that era, and certainly not the most respectable. It remains, however, the most emblematic. All at once, comics was the home of industrialized visual art; of serialization as an audience draw; of workers' rights abuses; of broad stereotypes and broader gags. Tim Hensley’s Detention No. 21 is a singular object which tries to encompass the eternity of that medium. It’s the story of comics as the story of the 20th century as the story of America. It’s ‘how we got here’. It’s also pretty good.

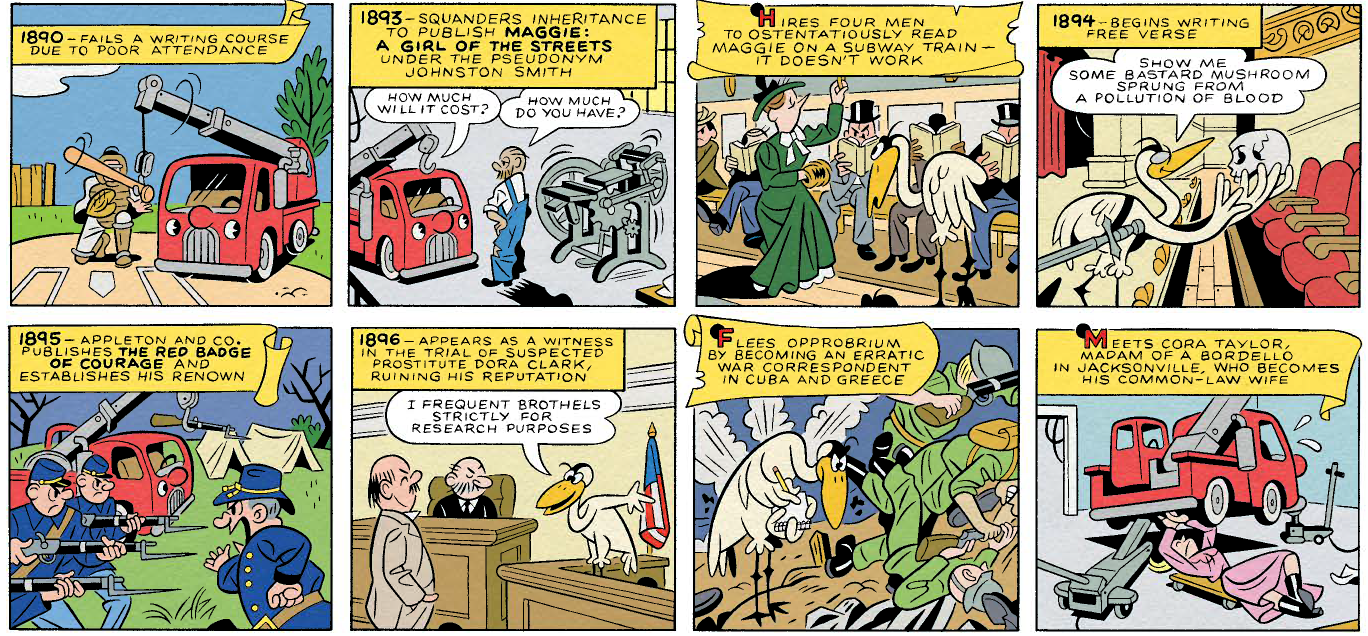

We’ll begin near the end: one and a half pages toward the back of Detention are dedicated to a biography of the American writer Stephen Crane. This makes sense, considering the bulk of the book is dedicated to an adaptation, in faux-Classics Illustrated style, of Crane’s Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893). The biography playfully begins by featuring Crane not as a person but two beings - a crane (the bird) and a crane (the mechanical device). The first of these pages is an extremely funny piece in which events from Crane’s life–all the highlights one could expect from a comics biography–are reimagined to fit either visual representation. The death of Crane’s father in 1880 is shown as an older bird being eaten by an alligator. Crane’s first meeting with his common-law wife, Cora, is shown as a female mechanic working on the underside of a vehicle.2 As expected, the first page ends with Crane’s death in 1900: “Riddled with debt, vomits blood[.]"

However, instead of stopping, the ‘biography’ continues for another half a page, in which time and events become jumbled: the panels move back and forth across time and space, from 1899 to 1908 to 1790. The ‘facts’ they present become just as jumbled and disconnected from reality as the visual representation - Crane’s father apparently invented LifeSavers candy in 1903 (just 23 years after his death, according to the previous page). The final panel of that sequence brings the two forms of Crane together, bird and vehicle, in a way that refuses to make any sense given anything that occurred previously.

This brings to mind Hensley’s previous outing, Sir Alfred No. 3,3 which likewise used the real details of famous person’s life as a springboard to play with, and to comment upon, the comics form. As Ken Parille wrote in his 2016 analysis of Sir Alfred, the work (and Hensley) seems thoroughly preoccupied with attempts made by the comics medium to translate and adapt other art forms, and likewise preoccupied with the people who made them. Comics, in Detention, becomes the defining art form of the 20th century because it can’t make sense of things. Because it is commercialized and industrialized. Because it transforms the ‘high art’ of Crane’s literature into the stuff of the masses.

In Sir Alfred there’s a small section dedicated to DC Comics’ The Adventures of Bob Hope series, which lasted almost two decades but managed to contain “not a single accurate biographical detail.” Another panel from the same section mentions Hitchcock’s inspiration for The Man Who Knew Too Much. By his own account,4 the movie first came to be as a result of reading a silent comic strip - unmentioned by name, but easily recognized as Punch artist H. M. Bateman’s “The One-Note Man” (1921). After mentioning this (true) statement, Sir Alfred then follows with a panel of Hitchcock reading a comic book of himself “comprised entirely of facts.” Needless to say, that comic book is made up.

These Classics Illustrated or Picture Stories from the Bible-type series sought to make make works from other, more worthy mediums into comics. Which meant: taking these critically-lauded stories and cutting them, rearranging them, omitting certain things. Reading a comics version of Moby-Dick (I have read about half a dozen) has as much to do with reading Melville’s novel as Hensley’s biography had to do with Crane’s actual life story: you might get the general shape of the thing, but you miss out on its depth. Even if the adaptation is a good comic by itself (such as the 1990 Bill Sienkiewicz version of Moby-Dick), it never quite manage to be the thing itself - the map is not the territory.

Which brings us back, all the way around, to Maggie: A Girl of the Streets. The cover of Detention boldly exclaims about its main adaptation subject: “Not one word has been omitted / But in fact several.” Stephen Crane died in 1900, which is symbolically important for what Hensley is doing here. ‘Comics’ as an art form was already a thing by that time, in historical terms; people can argue back and forth whether Hogarth or Töpffer or Hokusai ‘count’, but Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley did run during Crane's lifetime. Nevertheless, ‘comics’ was not yet a culture, an industry as we understand it, when Crane died. All these disparate creations, one-off cartoons and long-running serials, only became a cohesive whole later.

In Detention, Crane’s death becomes a breaking point in history, after which things become comics-ized. Which means: non-linear, cartoonish, and full of falsehoods. The biography goes off the rails. The original Maggie, comparatively, is as emblematic of American naturalism as any other novel you can point to,5 and seeks to present nothing less than the hard truths of life ‘on the streets’, in contrast to whatever falsehoods the characters, or the reader, might hold. Though he dramatized, Crane wanted to avoid melodramatics; everywhere his characters go, everything they choose to do, should be free of varnish. We should believe these people could exist right across the street. The titular Maggie, while not so much the protagonist (her no-good brother Jimmie gets the lion’s share of the text), nonetheless has all the signifiers of a romantic heroine that rises above her circumstances. Which makes it all the more painful when reality hits her in the face.

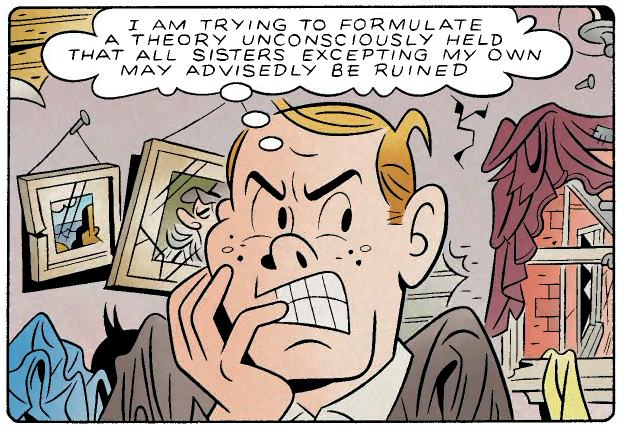

In one of the rare cases in which Hensley straightforwardly represents the text, he uses the opening line of Chapter 5 of the novel: “The girl, Maggie, blossomed in a mud puddle.” Unlike all the low-level trash around her, Maggie has something special that allows her to shine… or so she would like to believe. By the end of the novel, Maggie is just as besmirched as everyone else - at least in the minds of the people around her, who see her as a ‘ruined’ woman who has “gone to the devil.”6 She’s dead, though her hopes for greener pastures died long before her body. There was no other option for Maggie, because the streets that gave her life also held her back. No matter how much she struggles, she cannot escape her circumstances. Like Madame Bovary, she is a prisoner of her own romantic notions, who discovers life does not operate on novel-logic.

This is a rather grim outlook on life; a counterbalance to the American Dream of success-through-perseverance and innate worthiness presented in the popular works of Horatio Alger. However, Crane’s book wasn’t just a response to popular culture, or an attempt to copy the success of European authors. Writing honestly about the lives of the urban poor was becoming more accepted by that time, especially considering how turn-of-the-century America was itself becoming more urbanized. Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives came out three years before Maggie, in 1890, and appears to be a direct influence. Riis’ description of certain women who grew up in the New York City tenements might as well introduce Maggie herself: “And yet it is not an uncommon thing to find sweet and innocent girls, singularly untouched by the evil around them[.]”

But for all its investigative value, there’s something deeply unpleasant about Riis’ book. Not in its descriptions of the living conditions among the least well-off, which are grim but necessary, but in some of the conclusions Riis gleans from his urban excursions. Riis’ descriptions of various nationality-based enclaves, from ‘Chinatown’ to ‘Jewtown’ are filled with racial observations that makes one shudder today, even if they tend towards the positive rather than the negative. Riis is like a visitor looking at the human zoo: the lions do this, the zebras do that. This kind of metaphor only works if you consider people to be socialized in the same way as other species. Reading through Riis' book, one gets the feeling that these enclaves are inescapable and natural, a genuine outcropping of various ethnic groups’ normal state of being. This is mirrored in Crane’s point of view in Maggie, in which the very notion of bettering one’s status is considered as laughable as leaping tall buildings. Alger’s 19th century heroes had become the Supermen of the 20th - an impossible ideal to strive for, and an illusion of freedom for people forever held back by the social condition.

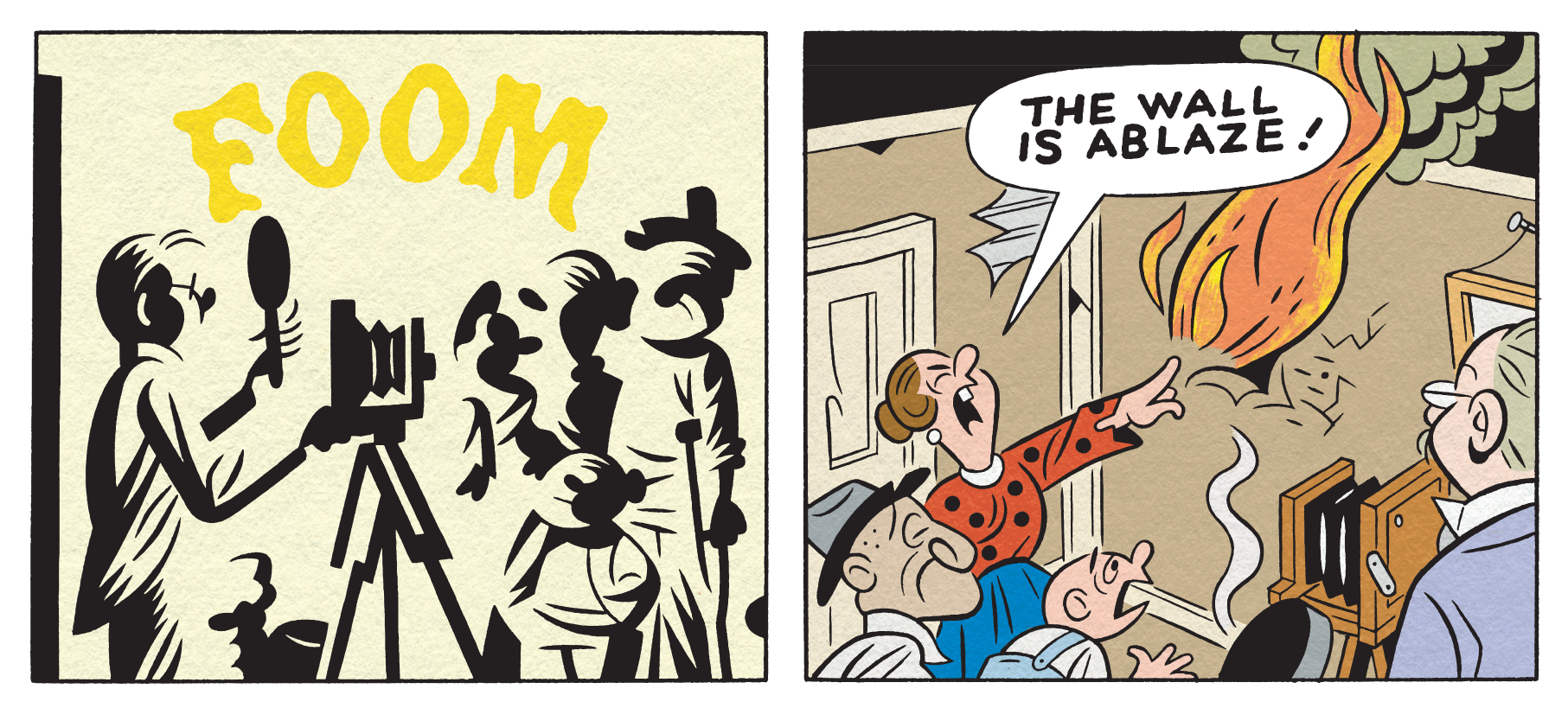

Detention certainly seems aware of these connections between Crane, Riis and American history. Another of the short semi-strips in the back of the book stars Riis himself. Also an important figure in the development of flash photography,7 Riis is presented by Hensley as a hapless disaster magnet. His new-fangled camera technology brings ruin upon its subjects, setting whole apartments on fire. Classic cartoon mishaps. We only see two pages' worth of “Jacob Riis: Muckraker” strips, but it’s enough to imagine dozens and hundreds more, each based on the same formula and ending with Riis torching some poor family’s house with his camera.

There’s something inherently fitting in the transformation of people like Riis and Crane into comic figures (which is to say, also comedic figures). Robert Warshow, one of the first in America to write about comics seriously, observed in 1946 that “the comic strip has no beginning and no end, only an eternal middle.” We meet these characters when they are already defined, and we accompany them on a journey without end. A character doesn’t so much ‘develop’ as it simply becomes more like itself. That this is considered comforting, something one can return to daily with the same certainty as the rising sun, is a commentary on America itself. The desire for things to remain as they are: a non-threatening social continuity.8 Riis and Crane wrote about people stuck in their circumstances. Little coincidence that so many of the protagonists of early 20th century comic strips were down-on-their-luck people, as were the majority of the readers. The ‘other half’ read more Comics than Crane. Hensley turns these authors into comic figures themselves. Even the solemn dignity of death is taken away, as seen in Hensley's Crane biography.

Another strong point Parille made about Sir Alfred is the manner in which the visual figure of Alfred Hitchcock is based on the Little Lulu character Tubby. To quote Parille: "It seems natural, almost inevitable, that Hitchcock should receive the kind of ‘cartoon treatment’ that Hensley gives him since he had already given it to himself." Slave to his character-defining passions, unable to learn or grow, with his 28 similar suits and his iconic profile,9 Hitchcock was already halfway there. Of course, Hitchcock was a real human being who grew old and changed (and died), but he sought to shape the perception of himself in a manner that preserved the ‘character’ of Hitchcock in the public’s eye. He sought to become a comic strip character - unchanging and unending. This trend continues in Detention, which freely utilizes familiar figures and architypes. As Joe McCulloch notes: “characters (or character types) from throughout the first half of comics history are deployed by Hensley as if they are actors taking the stage in period dress.”

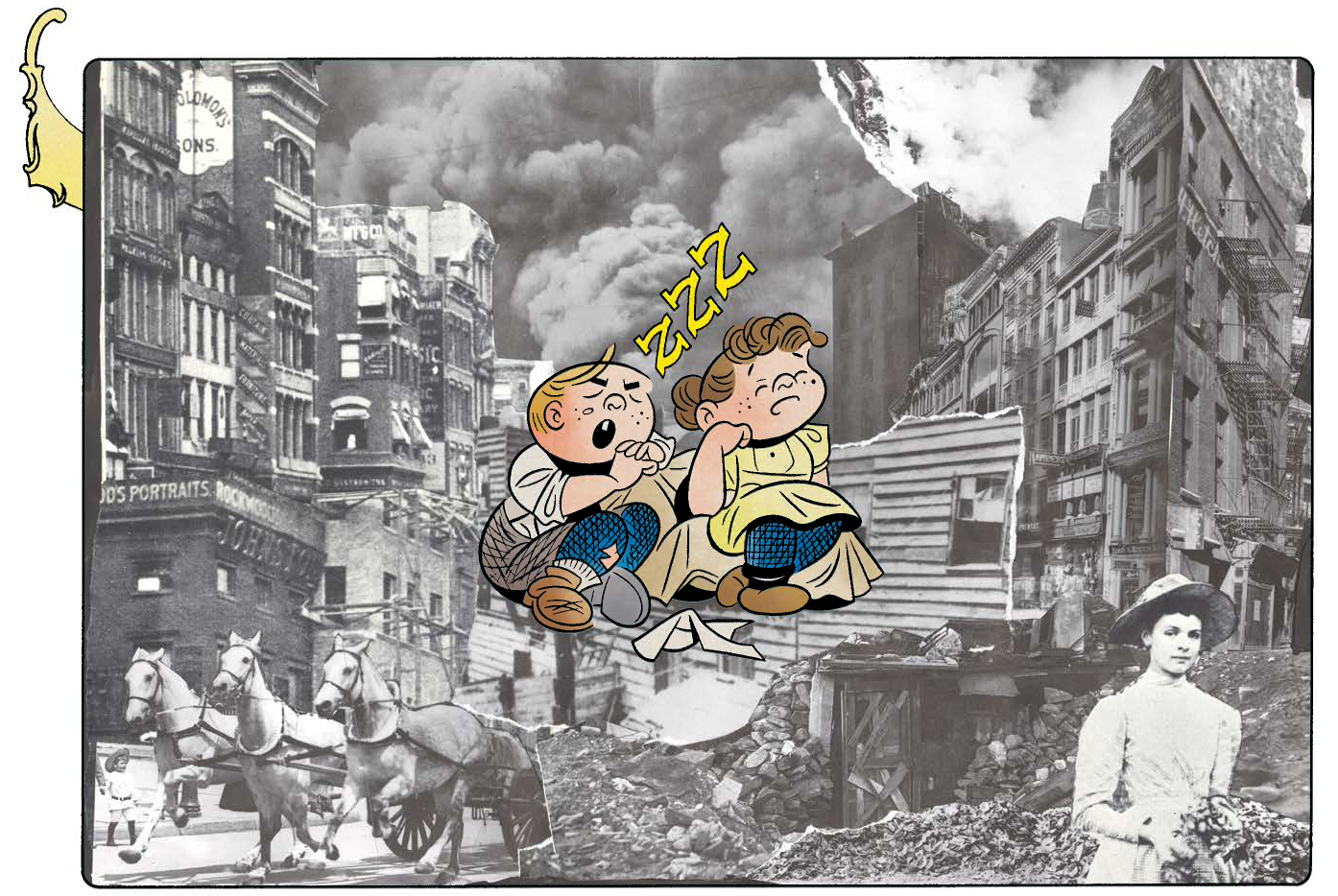

Whatever claim to realism the original story had, already shaken by Hensley's exaggerated comedic theatrics, is blown apart when we see the Yellow Kid dancing on the page, like casting Brad Pitt in a neorealist drama. Yet, astonishingly, under Hensley’s pen this all makes perfect sense. Hensley is not mocking Crane and Riis, nor does he mock comics itself.10 Riis’ and Crane’s work, their clear-eyed look at the realties of American poverty, made sense for the 19th century. In Detention, comics becomes the emblematic art form of the 20th century, the best way to engage with the confused nature of reality. The 20th century, in America at least, is the century of Urbanism: the end of the process Riis charted in the twilight of the 19th. And comics, as a medium, is defined by urban space. As the academic Benjamin Fraser remarked in his Visible Cities, Global Comics: Urban Images and Spatial Form (University Press of Mississippi, 2019), describing Joost Swarte's cover art to the second issue of RAW: “Not only is comics linked with industrial production and artistic representation in this image, it is also directly connected with the city, whose form it likewise reveals and conceals.”

In his version of Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, Hensley manages to convey the same ideas Crane had struggled with. He adapts the essence of the novel, not its outward form. His streets are no less dirty, his men no less cruel, his social pressure cooker no less crushing. Hensley simply does it with tools that were not yet fully-formed when Crane had died. If anything, the comics version of Maggie helps to emphasize the dire situation of the urban poor. After all, these iconic strip characters are as ‘locked in’ to their circumstances as the people Riis described. Happy Hooligan will always be a poor hobo, because being a poor hobo defines who he is. Not for him is Alger's happy ending. Jared Gardner’s Projections: Comics and the History of Twenty-First Century Storytelling (Stanford University Press, 2012), a book which seeks to explore the growth of comics as a mirror held to the 20th century, describes an early Happy Hooligan thusly: "One comic from 1902 offers 'a peep ahead' into the future, where Happy and his brother travel on rockets in a landscape defined by still greater speed, dangers, and possibilities. Despite the advances in technology, nothing in fact has changed: Happy ends up as he always does, as the reader is promised he will continue to do into the infinite future." Nothing, in fact, has changed. Nothing can change. Is there a more damning statement?

There’s just 40 pages to Detention No. 2. Yet somehow it appears that within these 40 pages (most of which are based on someone else’s words), Hensley has managed to compress the entirety of early comics history - as if serving the whole medium up on a platter, to explore the transition between the 19th and 20th centuries in America, the way that comics relates to our ability to understand and digest the nature of modern reality. The confusing faux-biography made up of half-remembered truths and outright falsehoods might as well have been any other historical thread in social media.

I am not sure if it’s right to say that comics had ‘made’ our present,11 but it certainly seems to embody it. One shouldn’t forget that behind all the cheap laughs (and some laughs should be cheap; the affordable price was part of the appeal of the comics section) there were hard truths lying in wait. Hogan’s Alley might be a funny place, but it’s funny in a bleak sort of way, where the death of child could easily be a punchline. These comics could also tell us how the other half lives.

* * *

- There is no issue #1. That is another layer of the gag - you can’t make sense of the serialization, just as you cannot make sense of the stories it tells.

- For a work of such intellectual heft, I appreciate Hensley's enthusiasm in going for some cheap, vulgar laughs. This is comics, after all.

- A work that I find less enjoyable, if still highly valuable, in its disjointed form. However, I cannot pretend this is not partly due to my incomplete Hitchcock knowledge; Sir Alfred works best if one knows Hitchcock’s movies and biography inside and out. Detention, comparatively, is occupied mostly with a singular work by a short-lived author - and, from personal testimony, the main body of the work functions just as well if you are not familiar with Maggie beforehand.

- Assuming one choses to believe Hitchcock, a man seemingly as desperate to control his public image as he controlled his movie sets.

- Unless you point to McTeague.

- One of the finest moments in Detention is a panel with a close-up on Jimmie’s face as he thinks: “I am trying to formulate a theory unconsciously held that all sisters excepting my own may advisedly be ruined.” His face has that slightly familiar expression of cartoon characters when they are caught a lie, the big open mouth with two large rows of teeth, lips turned slightly down and eyes beading all the way to right. Usually a comedic device, Hensley instead turns it into a crushing moment in which society’s entire chauvinistic tendency is shown as an ‘ain’t I stinker?’ moment. Cognitive dissonance brought up, only to be easily dismissed.

- Several panels throughout Detention contain cartooned images superimposed atop old pictures of urban scenery - the collage of reality giving way to the cartoon form. It's as if Hensley is intentionally drawing our attention to the 'fakeness' of comics.

- The American academic Arthur Irving Gates recognized the addictive nature of the comics strip format and other habit-forming newspaper features in a 1921 article for the magazine Circulation: “A stronger, more reliable, more permanent source of satisfaction is the familiar—the attraction of the things to which we are adjusted by habit…. Once the habit gets under way, it takes care of the separate acts of the future…. It requires but little ingenuity to enlist these fundamental characteristics of human nature in the service of the newspaper.”

- Is there any more common advice for character design in comics than to have easily identifiable silhouette?

- At least, not beyond what it deserves. We are not quite at the Chris Ware level of performative self-loathing.

- To quote the novelist Jarett Kobek, himself quoting the critic and podcaster Jeff Lester, in his book I Hate the Internet (We Heard You Like Books, 2016): “[…] the comic book industry more or less conquered the world. And I’m not just talking about the proliferation of superhero movies or whatever: I mean the practices of the industry–dubious labor practices obscured by an endless supply of wiling freelances, the emphasis of brand over individuals… the constant need for content–are now how so many other industries operate.”