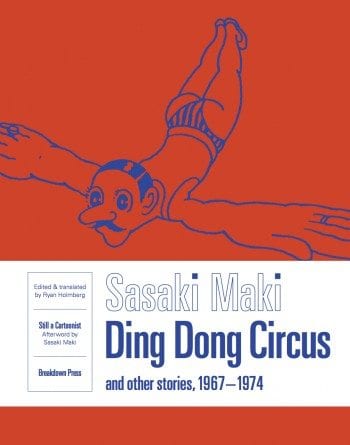

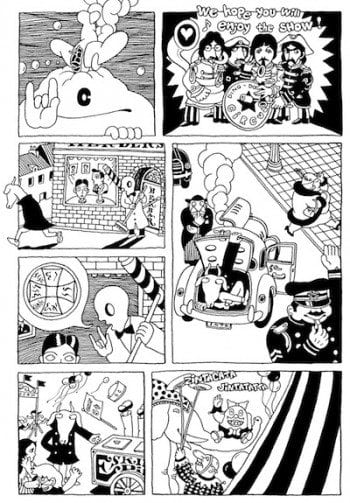

What you see to the right is the cover of the latest manga title from Breakdown Press: Sasaki Maki's Ding Dong Circus and Other Stories, 1967-1974. It was organized and translated by me, has an autobiographical essay in the back by the artist, and was sponsored, like the previous two Breakdown manga titles, by the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures.

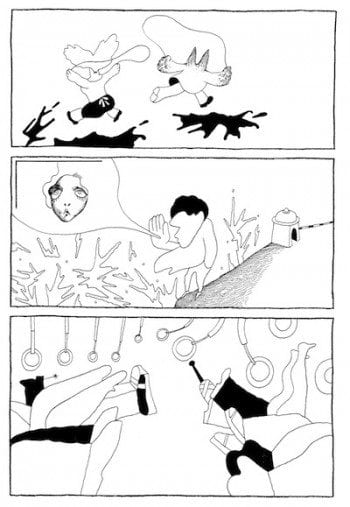

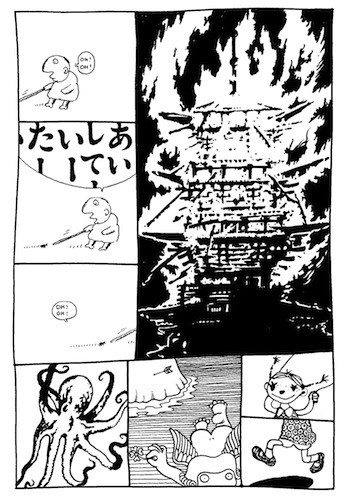

As the blurb on an inside flap explains, “This collection presents, for the first time in English, the best of Sasaki Maki’s work, mainly from alt-manga super magazine Garo. Drawn between 1967 and 1974, the fifteen stories here follow Sasaki’s groundbreaking exploration of collage methods in comics storytelling, weaving through references to R&B, rock ‘n’ roll, the Vietnam War, Andy Warhol, the Summer of Love, the Beatles, British humour, and the wacky world of Japanese consumerism. Ding Dong Circus demonstrates what manga fans already knew: that in Sasaki Maki, Japan can claim not only a pioneer in experimental comics, but one of the world’s masters of Pop Art and a trenchant avant-garde critic of the Sixties.”

I breathe a heavy sigh of relief that this book is finally coming out. I say “finally,” not because Breakdown dragged their feet or anything like that, but because I have wanted to do an English-language edition of Sasaki Maki’s work for almost ten years now, but was stifled at various turns. Dan Nadel might recall me coming to his Carroll Gardens studio around 2007 to propose the project. “It’s really hard to sell this avant-garde material that doesn’t have any narrative,” he said to me, pushing instead Sugiura Shigeru, Takeshi Nemoto, and Terry Johnson ... all of whom, of course, are master storytellers. [Editor's note: I think I was using code for: "I'm not that into this stuff." Avant-garde non-narrative is my middle name.] So I shoved off with a free copy of The Ganzfeld and tried for a few years to be a university professor before the same Mr. Nadel fished me out of the academic ghetto and gave me a shot at living in the comics world slum. He got his Sugiura book (serves him right), soon after which PictureBox was placed into cryogenic freeze, leaving me scurrying to find new patrons.

Around the same time, an acquaintance in Delhi expressed interest in publishing manga. He said he wanted to do something crazy (and something that wouldn’t be axed by Indian censors), so I proposed Sasaki Maki. He said okay, cool, great, and much to my surprise, Sasaki Maki and his agent gave the thumbs-up to a publishing venture that was sure to make them less money than the cost of the phone call to tell me yes. What turned them on, I think, was the simple bizarreness of the idea of avant-garde manga in India. (Maki is a big Beatles fan, by the way.) I liked that idea too. I had this fantasy of the book printed either by one of the Muslim print shops in Mumbai who do these rad purple-green-pink posters that you find glued to highway pylons in the Muhammad Ali Road area, or this silkscreen outfit in Agra that I discovered upon seeing its posters for a touring magic show in Chittor.

For better or worse, my Delhi collaborator slithered away and the book never happened. As luck would have it, some months later I met the bearded boys of Breakdown Press while on a research grant in England from SISJAC, and got them to take on the Sasaki Maki project, and since then much besides. Now ten years and five countries later, the book is coming out. There is a number of people I can thank for help making it happen, but there’s only person I can imagine dedicating it to, and that is myself ten-plus years ago. Because it was a younger me that was happily deluded by Sasaki Maki’s artiness into thinking that he could write a successful art history dissertation on alternative manga.

Sasaki Maki was not the first Garo artist I got into (that would have been Tsuge Yoshiharu or Shirato Sanpei), but he was the first I tried to write about seriously, outside of the classroom anyway (I wrote a seminar paper on Shirato’s Ninja bugeichō for John Whittier Treat my first year in grad school), and with the interests of the art world and art history in mind. Sasaki Maki’s work also became a doorway to meeting a number of professional colleagues in comics without whom I’d be nowhere. I first learned about Maki via a brief discussion of “The Vietnam Debate” (1968) in Natsume Fusanosuke’s Manga and War (Manga to sensō, 1997). That Maki work became the focus of a paper I did for the Whitney Independent Study Program in 2004, which turned into the essay reprinted below. While translating “The Vietnam Debate” for the Breakdown collection, it blew my mind all over again: deceptively simple, strategically superficial, and utterly brutal if read attentively with a little knowledge of contemporary Japan. Situationist détournement was too caught up in jargon to ever do anything so effective.

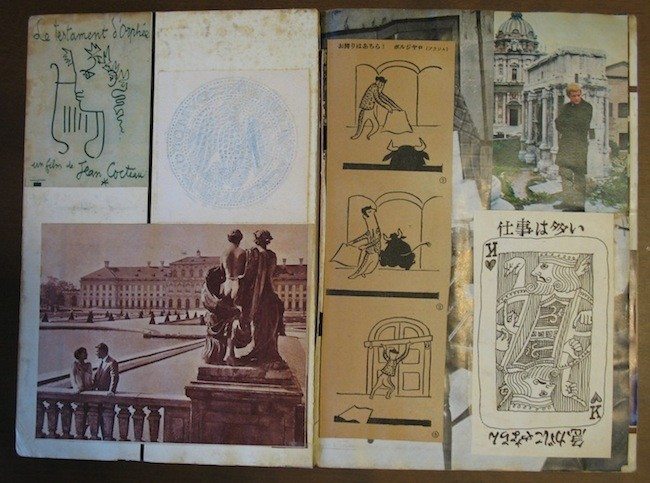

While trying to contact Sasaki Maki through a Garo fan page in Japan, former Ax editor Asakawa Mitsuhiro got in touch with me to help, and has been selflessly helping me ever since. Years later I ended up at Gakushuin University on a postdoc, coincidentally under the guidance of the same Natsume Fusanosuke who wrote Manga and War, and who turned out to be a maniacal Sasaki Maki fan. When it comes to my relationship with Natsume-sensei, I have done far more taking than giving. But once, I think, my demanding gaijin-ness might have seemed worth the hassle when I asked him to accompany me to interview Sasaki Maki in 2011. I got in no more than ten words the entire interview, as the silver-haired and normally gentlemanly Natsume jabbered away like a schoolchild, clearly enamored with finally meeting one of his youth idols. I would be like that if I got to interview, maybe, David Yow. Anyway, I sat nodding in the corner, repeating a-sō and naruhodo ne, while diligently stuffing my mouth with these tasty little cookies Sasaki Maki’s daughter had made. My “a-ha” moment was when Sasaki Maki showed us his scrapbook (see photo), and suddenly his visual imagination and art historical roots became clearer.

Pretty soon, I am headed back to Tokyo to work on some writing and translation projects looking at the intersection between Pop art, manga, music, and the American military presence in Japan from the 50s and 70s. The goal is to bring together, in book form, some of the articles I have written over the years on cartoonists like Saitō Takao, Hayashi Seiichi, Sugiura Shigeru, and Sasaki Maki, and art world artists like Haraguchi Noriyuki and Shinohara Ushio. The idea is to go back and do properly what I could only do poorly when I first started writing on Garo and Sasaki Maki, and that is to bridge manga and contemporary art in a way that doesn’t reduce one to the caricature of the other. I have some other projects to finish before throwing myself into that, but in the meantime I can get the ball rolling in the right direction, while marking the publication of Ding Dong Circus, by going back to my own beginnings as a manga historian and taking a look at one of the first serious essays I wrote about Garo: “Hear No, Speak No: Sasaki Maki Manga and Nansensu, circa 1970,” Japan Forum 21 (1) 2009.

Another reason I am reprinting this essay here is that, otherwise, most people interested in Sasaki Maki and Garo won’t have a chance to read it. While Japan Forum is a superb journal, it is published by Taylor & Francis, which means that to download my article legally you either need to shell out 40 USD to the publisher or belong to a library wealthy enough to afford access to expensive academic journals. In a world where almost no one is making money on their writing (the humanities in academia), and where a “peer review journal” (whatever that means today) can be done more effectively and cheaply online, I see no good reason to let research get locked up by these academic outfits. According to the Taylor & Francis site, the original version of my article has 91 views since it was published in 2009. I suspect people have read it through other channels, but at a meager 91 views obviously Taylor & Francis is not doing their job in spreading knowledge. I know I write for a niche audience, but I also know there are more people than that who like to read about strange manga – so here you go.

While I disagree with some of the things I wrote in the original essay, and no longer appreciate the style (was smoking a lot of weed in those days, reading lots of Samuel Beckett, and feeling very NYC art world intellectual), I am reprinting the essay as is, with a handful of comments on how I think differently now and where I might take this essay once I return to Tokyo and shift full time into championing manga as the king of Sixties Pop.

(cont’d)