The recently completed Punisher: Soviet (the first issue of which was already reviewed on The Comics Journal by Matt Seneca) is a weird series. Were it not for the fact that is a real comic-book series, with familiar names on the cover, including the ever-prolific Garth Ennis and the better-than-ever Jacen Burrows, I would suspect this story of being a piece of fanfiction. This isn’t the Punisher’s story. He’s just a witness, an Ishmael, to the story of Valery Stepanovich. Stepanovich is a former Soviet soldier who’s out for revenge against the officer who sold him and his men out.

You see, this is the story of the one man the Punisher respects. A hard-as-nails soldier who can confide in Frank Castle - knowing the two share some invisible soldiery connection. Valery is so badass the Russian mob is actually convinced he’s the Punisher (hence the pair's initial meet-cute). From story beats alone it’s the type of thing I would expect to see in a tale uploaded by a Russian teenager unto fanfiction.net; yet here it is, black and white and red on paper.

Still, even though Ennis is basically using The Punisher brand as an excuse to indulge in his Soviet war stories proclivities Punisher: Soviet turns out to be a hell of a ride, and very much in the vein of previous works from Ennis like 303, World of Tanks: Citadel and Battlefields: Night Witches. At this stage of his career, three decades in (and having done nothing else since the age of 18), Ennis' storytelling instincts are strong enough that he can never quite fuck up in the same way other professionals manage to. Ennis knows how to think up a story, how to break it into a script, how to execute his ideas. Even a work as minor as, say, Red Team has more forward momentum and thematic resonance to it than 99% of the things in the direct market. It’s like a Donald E. Westlake thrillers once he hit his stride – Garth's work just has a groove to it that keeps it readable. No matter the publisher, no matter the artist (and Ennis had worked with both the best and the most mediocre the direct market has to offer). Ennis writes comics that work.

The other thing that makes this series work is Burrows’ art. I know I’m in the minority, especially among The Comics Journal critical crew, but I was never a big fan of his previous works. It is true that there were many impressive moments in Providence, especially as the series nears its apocalyptic finale. The amount of research Burrows invested in the architecture and clothing of the time period must have been maddening. One could also never deny Burrows’ willingness to go for broke with nastiness (see – the village bombing scene in 303, the rape scenes in Neonomicon or any other page of Crossed). Still, I always found his figure-work a bit static and lacking in elegance. There's a certain dull edge even to his most vicious moments. Reading Punisher: Soviet made me reconsider. The old faults now appear to me the result of bad coloring, drowning a fine line in murk, making the bodily texture rubbery and dull and robbing faces of clear expression.

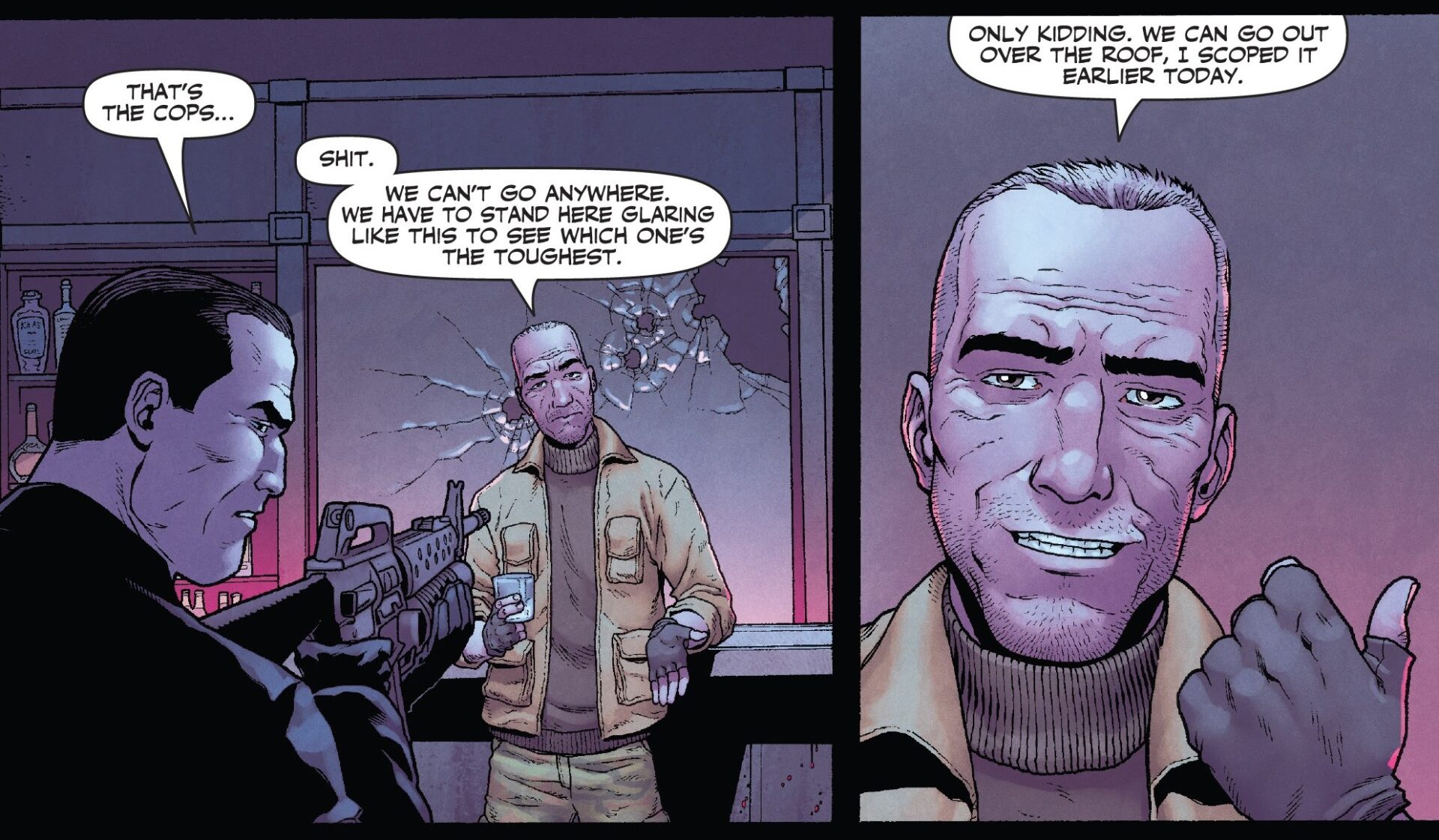

Punisher: Soviet is colored by Nolan Woodard and inked by Guillermo Ortego. They do justice to Burrows’ work, accentuating his strengths and moderating his weaknesses. There’s particular great bit of cutting in the first issue: Punisher leaves a bunch of explosives in his van and descends into the underground while some gangsters open fire. In the next page he goes back up we see only the result of the explosion. Superbly restrained by Burrows’ standards, but bloody enough to be exciting. The art is simply methodical and straightforward, as befitting for an Ennis story, avoiding all clutter and treating all human cruelty as natural byproduct of existence. Burrows neither delights nor is repulsed by what he depicts. This makes him, possibly, the most appropriate art on a Punisher series ever (not ‘the best,’ just ‘most appropriate’).

The success of Burrows’ work on Punisher: Soviet, and the way it compliments Garth’s usual interests (‘hard men pay for the mistakes of their masters') brought me to another recent Soviet-themed six-issue series written by Ennis. Sara, from TKO Studios, which was drawn by Steve Epting. Now, Epting is certainly a higher-profile artist than Burrows, especially in direct market terms. He’s been in comics just as long as Ennis has, and he's worked for DC, Image, First, Crossgen and Marvel - where he made a name for himself drawing the fifth Captain America volume (the one with the Winter Soldier).

Epting has all of the chops you’d want for an action-adventure artist. He’s got strong figure-work, he’s got style and energy and knows how to do a big exciting splash-page. Epting even comes ready-made with experience in drawing World War II-era tech and uniforms. Still, despite the pedigree Sara doesn’t quite work for me the way Soviet did. In story terms we are closer to territory Ennis loves to play with it: It’s a World War II series, the hell known as ‘the Russian front.’ The series follows the titular Soviet sniper, part of an all-female unit, as she ventures past enemy line day after day to collect targets. Sara is just like Ennis’ typical male protagonists, a professional killer whose thoughts are occupied only by battle strategies and her place in long history of human bloodshed. Usually, when Ennis writes female protagonists they have to deal with a lot of chauvinistic bullshit, so we’ll understand that this hard world is even harder for them, but here it’s mostly put to the side.

Sara’s most important trait, just like Valery Stepanovich, is that she’s the common ground soldier. A tool used by a higher powers that fail to appreciate her. It’s a common theme in military fiction. Armchair generals that laugh and smoke cigars while the corporal dies in the mud. The reason it is so common is because it feels right and true; an extension of a civilian's familiarity of how bosses often treat their employees (only with bullets instead of lost e-mails). Indeed, one wouldn’t be too surprised to learn that the big twist ending involves Sara learning her family was killed not by German forces but by her own people, causing her to lose whatever little faith she had left in the system she serves. She nevertheless completes her final assignment, killing a top enemy sniper, with a particularly well-established Chekhov's gun (or grenade, in this case). It’s the sort of professionalism one can expect from Ennis, but it never quite reaches the levels of insight into faulty systems we can find in his better works.

While the lack of grittiness in there in the story, nothing in the script would prevent this from being a PG-13 film, which is really apparent in Epting’s art. Everyone is just too pretty. All the women look like they could be models, with their symmetrical faces and well-kept hair. Even Vera, whose characterization is that she’s big and scary and violent (a blunt instrument among blunt instruments) just looks slightly lumpy. None of them looks like they’ve been through a harsh Russian winter, never-mind a harsh Russian war.

In the hands of another writer this could’ve been a major plot-point. These women are part of a propaganda effort, but Sara (the series) puts this notion to aside almost as quickly as Sara (the character). She’s here to kill Nazis, not to play for the camera. Problematically, the lack of self-acknowledgment means that the series does tend to become that which it criticizes: it’s too pretty, and it's too clean. For all the technical details, the makes of rifles and tanks, the right ranks on the right uniforms, I just don't buy the world it depicts. Sara can talk all she want about the war being ugly and mean, but the art doesn’t sell her words. It feels like a Hollywood movie. It might be the right kind of movie, a classic TCM feature with all the stars a grandfather remembers in black and white, but it’s a movie nonetheless. Not a war story, but the story of other war stories. Familiar.

Which is not to say that Sara is bad. Again, Ennis doesn’t really write ‘bad’ anymore. Nor is the art a complete waste. I like the bit in chapter 2 where Sara learns to snipe and the opposing soldiers' faces simply turn into a small cloud of red mists. Epting is also superior to Burrows at presenting depth. His panels have more layers to them, making him better suited for the long scenes of characters staring silently at the abyss, waiting for it to twitch. Yet for all the skills at play, Sara just doesn’t give me what I want. Nor does it give me what I think the creators are capable of.

Both works (and the other Soviet-themed comics I mentioned earlier) speak to Ennis’ general interest as a writer. Garth Ennis is a war story writer. He writes lots of other stuff - horror (A Walk through Hell), comedy (Dicks), crime (Red Team) – but almost everything he writes ends up touching on war in some way. There will be a veteran character, or a backstory involving some shady politician selling illegal weapons, or something else to that effect. Chris Hedges wrote “War is the force that gives us meaning,” and Ennis seems to take this notion to heart.

Ennis is also a writer with sharp interest in American society and Americana, part of a crop of British writers who made it their mission to explore American psyche (Moore, Milligan, Morrison). Even when he’s writing about the Soviets you feel like he’s writing about America: This is what happens when a mighty Empire topples, this what happens when you make war into a business.

Valery Stepanovich and Frank Castle can bond because they’ve both been through the shit (Vietnam, Afghanistan). This bond also presents to us a particular trait of Ennis: he’s very good at judging societies. The “Valley Forge, Valley Forge” arc in Punisher: MAX and the sister series, Fury: My War Gone Bye, are two of the frankest and most brutal examinations of American foreign policy throughout the 20th century. It features the kind of stuff you expect to be found in a Marxist thesis read by 200 people, not something published by a subsidiary of Disney.inc.

Yet Ennis can never quite be the true cynic he wishes he were, like his creative father John Wagner. He loves his hard men (and women) too much, and throughout Punisher: Soviet we see numerous flashbacks to Stepanovich’s service and the narrative takes it in stride that he and his comrades did terrible things to the people of Afghanistan. The story only becomes scornful when the villain, an officer who (naturally) never saw combat, is introduced. The climax of the story punishes him by teaching him what the men he betrayed had gone through. John Wagner could judge the choices these hard man make, the death they deal along the way, whereas Garth Ennis looks up to them a bit too much.

Possibly it has to do with the fact that he never served in the armed forces. For all his knowledge and research, and you can be quite sure he knows his guns better than Kenichi Sonoda, there’s always some element of ‘respect the troops’ creeping into his writing. This is especially true when dealing with the Russian soldier whose suffering his legendary. Enemy on the front, political officers at the back and commanders all too willing to plug the enemies’ barrels with bodies if needs be. In both Soviet and Sara the ability to endure horror, to become the tool that cuts through it, is a virtue independent of context. It matters little what the soldier is fighting for, only that he fights well and that he do not betray his comrades.

Sara falters, I think, because the art ends up agreeing with Ennis, playing up the heroic affect of the story. Sara’s final sacrifice might be written as her going with her own truth, and against the wishes of her superiors, but in the it has the look of the propaganda effort she so despised. Punisher: Soviet is just ugly all the way through, which is the way it ought to look. It is also just the right type of ugly, a matter-of-fact way which reveals what we all are inside. A mix of blood, meat and bones, barley held together by the skin which gives us a semblance of humanity. Ennis simply sees deeper into us.