Ron Goulart, one of the key links among science fiction, comics, pulp fiction, detective fiction and fandom, died Friday, Jan. 14, at the age of 89.

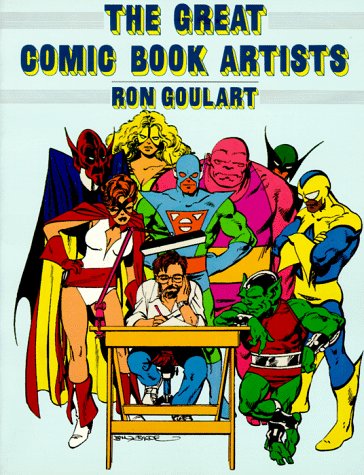

He was such a prolific writer that it’s doubtful any complete bibliography exists, but it’s safe to say that he published more than 180 books of fiction and nonfiction in his lifetime, often writing under pseudonyms. He produced three books about comics in 1986 alone and a total of at least 17 books of historical commentary in his lifetime (including The Hardboiled Dicks: An Anthology and Study of Pulp Detective Fiction – 1965; Cheap Thrills: An Informal History of the Pulp Magazines – 1972; The Adventurous Decade: Comic Strips in the Thirties – 1975; The Great Comic Book Artists – 1986; Focus on Jack Cole – 1986; Ron Goulart’s Great History of Comic Books – 1986; The Dime Detectives – 1988; The Comic Book Reader’s Companion – 1993; The Funnies: 100 Years of American Comic Strips – 1995; Comic Book Culture: An Illustrated History – 2000; Comic Book Encyclopedia – 2004; and Alex Raymond: An Artistic Journey – 2016).

In the area of fiction, he wrote more than 26 stand-alone novels (including Clockwork Pirates – 1971; When the Waker Sleeps – 1975; The Enormous Hourglass – 1976; The Robot in the Closet – 1981; A Graveyard of My Own – 1985; and Now He Thinks He’s Dead – 1992). But he really liked working with ongoing characters and created or contributed multiple novels to at least 13 fictional series (including Flash Gordon, The Phantom, Vampirella, Avenger, John Easy, Barnum System, Odd Jobs, Inc. and Fragmented America). He was ghost writer of several of the pulp novels attributed to “Kenneth Robeson”, as well as the TekWar novels and TekWar comic books, based on outlines supplied by William Shatner, whose name was on the books.

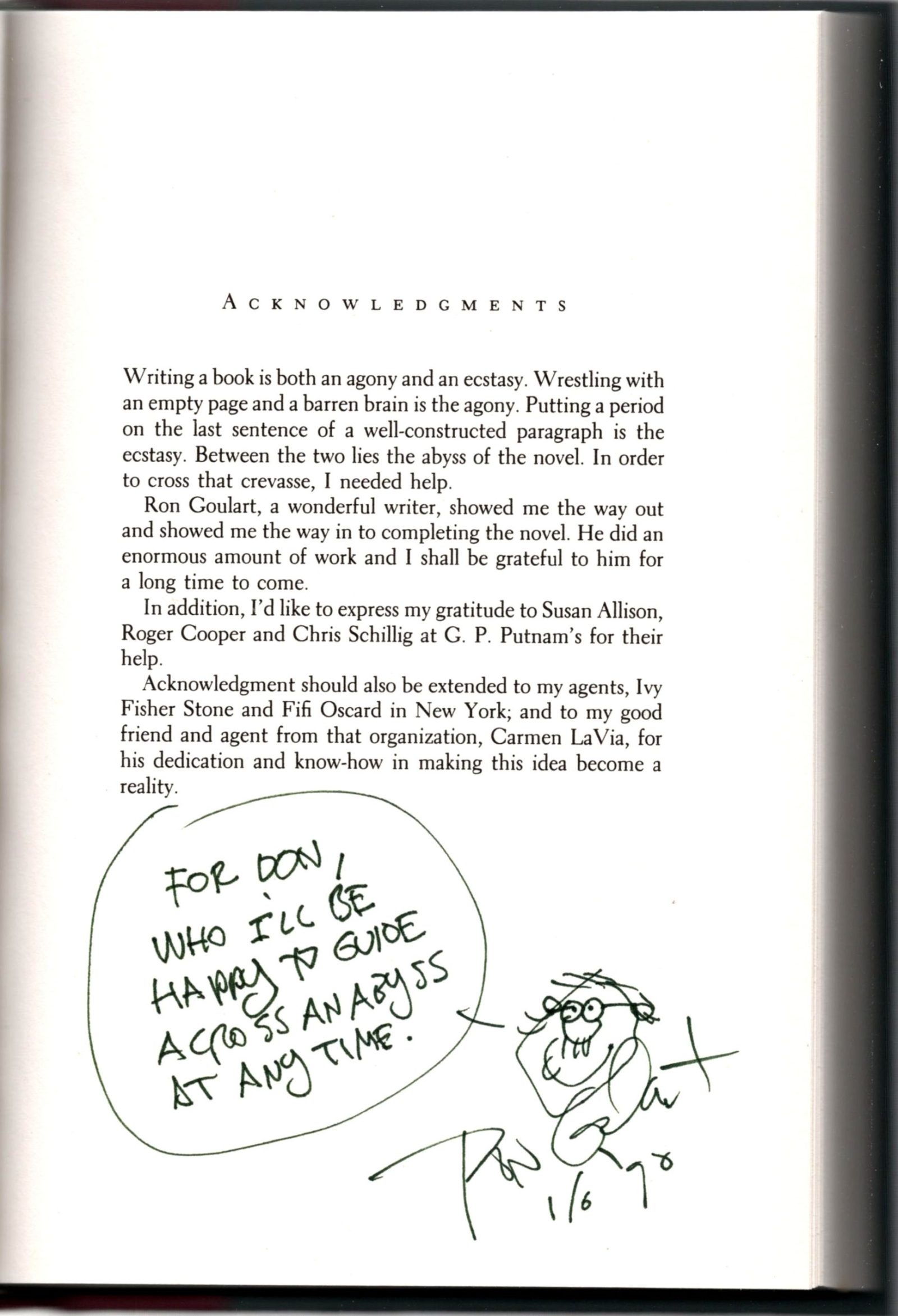

Maggie Thompson, who co-edited Comics Buyer’s Guide with her husband, Don, told TCJ, “His friends knew that Ron wrote the TekWar adventures, but he refused to autograph the title page of our copy, when we asked him. Though he was usually nice enough to autograph things for us, he commented that the only creator information on that page was that of William Shatner. We pointed out that his name did appear on the Acknowledgements page. Hah!”

Maggie Thompson, who co-edited Comics Buyer’s Guide with her husband, Don, told TCJ, “His friends knew that Ron wrote the TekWar adventures, but he refused to autograph the title page of our copy, when we asked him. Though he was usually nice enough to autograph things for us, he commented that the only creator information on that page was that of William Shatner. We pointed out that his name did appear on the Acknowledgements page. Hah!”

In addition, Goulart wrote the comic strip Star Hawks with artist Gil Kane, scripts for five different TV series (Monsters, Welcome to Paradox, Tales from the Darkside, ThunderCats and TekWar), adaptations of classic SF for Marvel Comics and countless short stories (including at least eight story collections) and magazine articles, including a column for The Twilight Zone Magazine. Novelizations by Goulart include books of the 1978 film Capricorn One, the 1978-79 Battlestar Galactica TV series, and, oddly, two 1970s blaxploitation films featuring the character Cleopatra Jones.

He was born Ronald Joseph Goulart on Jan. 13, 1933 (living to see his 89th birthday the day before he died) in Berkeley, California. His affection for popular culture grabbed him at an early age and he began corresponding with The Saint creator Leslie Charteris while still in junior high school, where he was staging and starring in plays about heroic figures like Robin Hood. His “Letters to the Editor” parody, written, while a student, for UC Berkeley’s humor magazine The California Pelican, became his first professional publication, appearing in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1962.

Thompson said, “Don and I had admired Ron’s work when we were both just science-fiction fans, separately enjoying ‘Letters to the Editor’ when it first appeared, introducing readers like us to his wonderful wordplay. I no longer recall how it was that we first met Ron — or even whether it was via correspondence or at a convention. But he was a never-ending source of information and delight. In any case, he contributed an article on comics pioneer James Swinnerton to our Comic Art #4 (December 1962) fanzine — and that article was based on information he’d gathered from Swinnerton himself. In the years that followed, we were continually amazed at and delighted by his knowledge, painstaking research and insights about the entire pop-culture universe, as well as his interactions with some of the giants of the field of comic art. By the late 1980s, he was providing CBG with installments of such series as ‘Funnies in the Thirties’, ‘Funnies in the Forties’, ‘Before Superman’, and ‘Old Original Super-Heroes’.”

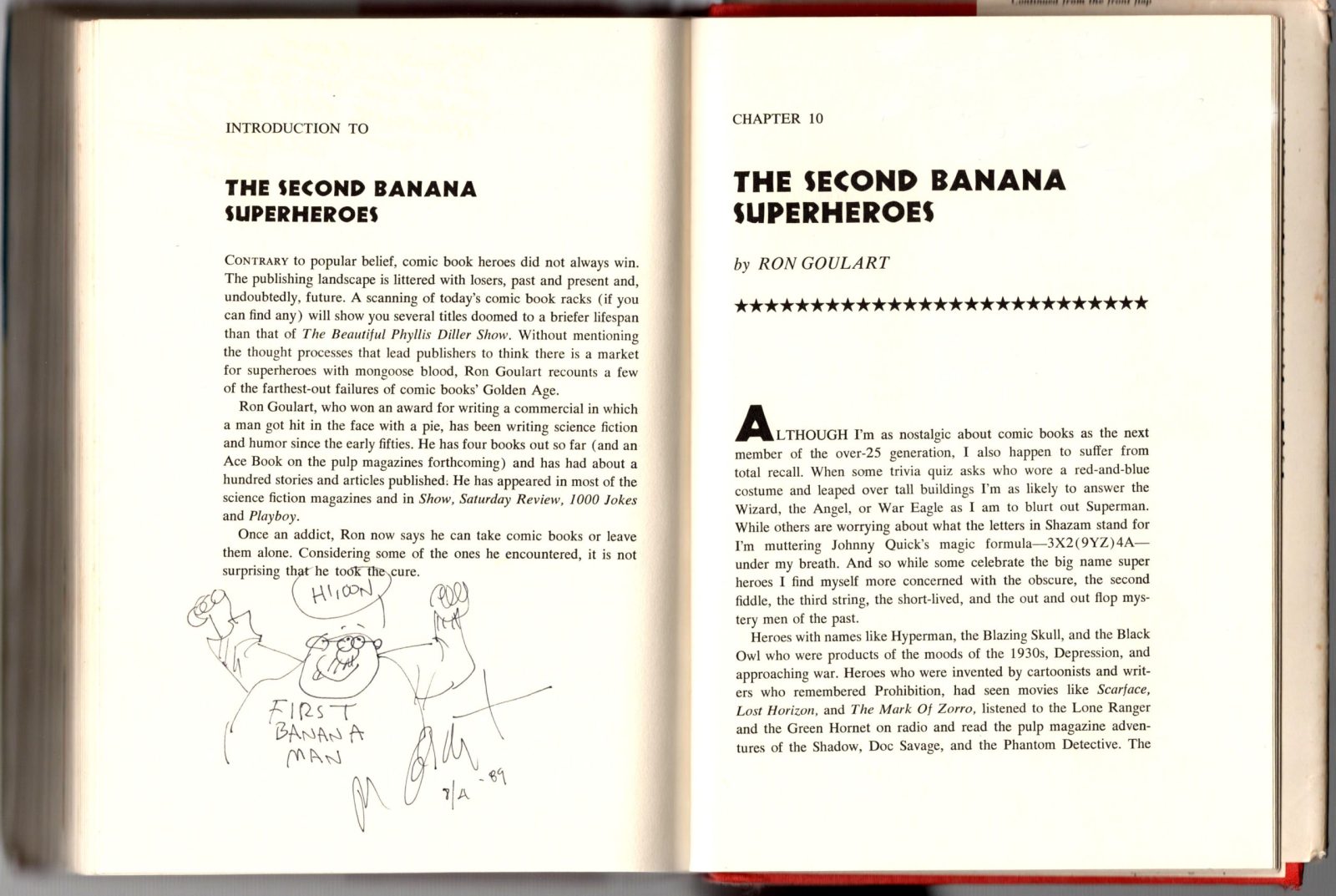

She added, “Ron didn’t contribute to the original All in Color for a Dime series of nostalgic Golden Age comics articles that ran in Dick and Pat Lupoff’s Xero science-fiction fanzine, but he was a natural choice to provide a comprehensive article, when it came time for the eventual 1970 book publication. His ‘The Second Banana Superheroes’ feature therein reminded readers of the plethora of other super-characters of that early era. As did his ‘The Second Banana Strikes Again!’ in The Comic-Book Book three years later.”

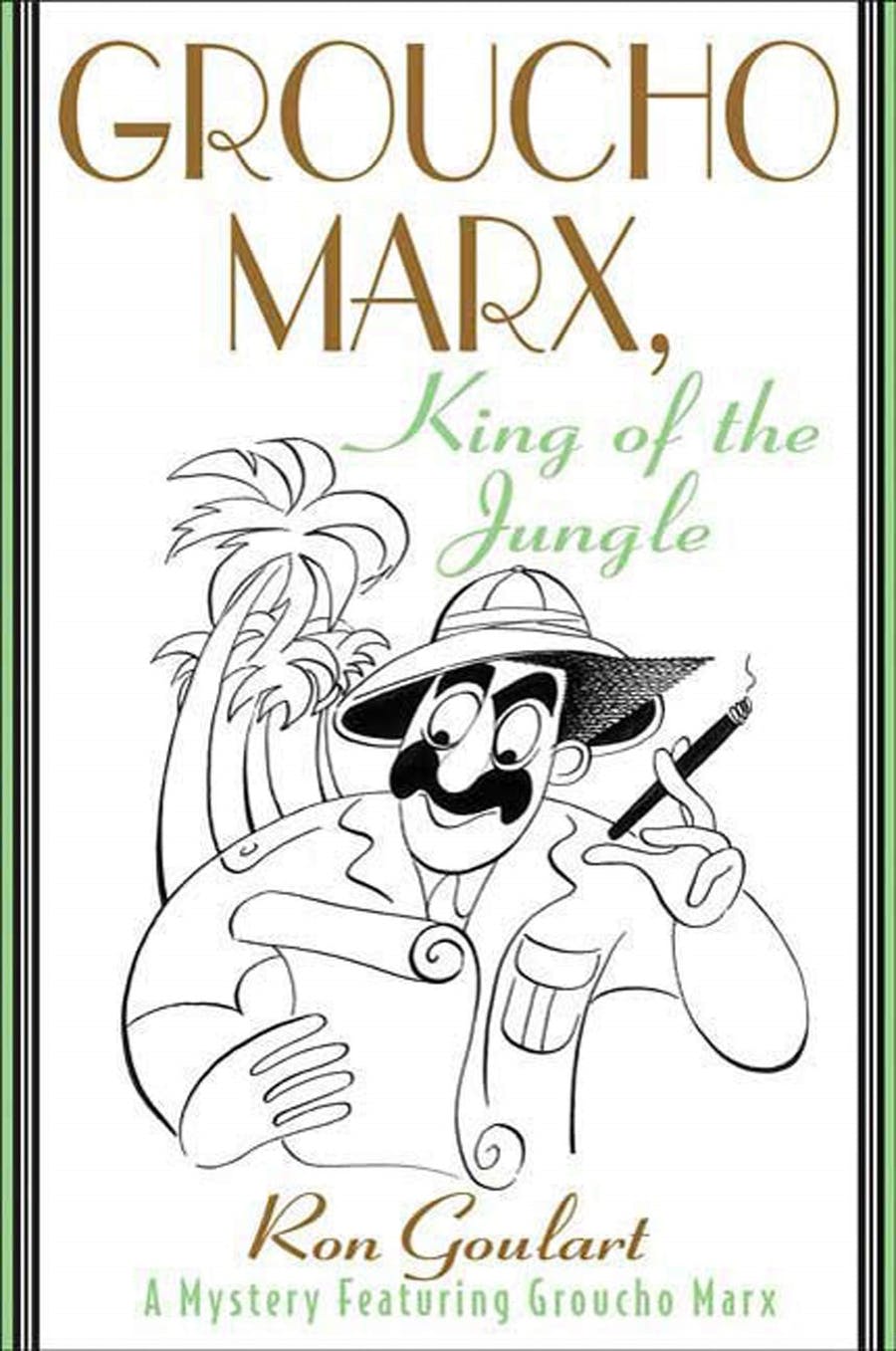

His day job after graduation was with an ad agency, where he created the Chex Press newspaper parody that appeared on boxes of Ralston Purina’s Rice Chex, Wheat Chex and Corn Chex cereal in the 1960s. Goulart’s time in the advertising business may have instilled in him the straight-faced sense of absurdity that characterized much of his fiction. His name might not be found among the first tier of canonical science-fiction or mystery writers, but it’s hard to think of a writer who seemed to be having—and offering—more fun than Goulart. He was, after all, the creator of a series of mystery novels with Groucho Marx in the detective role.

Thompson said, “When he signed his writing—whether in casual letters or in more formal autographs—Ron went to the extra effort of adding a self-portrait and, sometimes, more. When he autographed my copy of Groucho Marx, Private Eye, he added Groucho. When I asked what his approach had been when it came to providing conversation for his detective, he commented that the trick had been to pay attention to the way the star talked when he was not being scripted by someone else: when he was, in short, talking as Groucho himself, not as (for example) Rufus T. Firefly or Otis B. Driftwood.”

Goulart was nominated for a Nebula Award for “Calling Dr. Clockwork”, which appeared in Amazing Stories in 1965. His 1970 novel After Things Fell Apart, which formed the basis of his Fragmented America series, was nominated for an Edgar Award and came in 16th place in the science-fiction and fantasy Locus Awards. And his Comic Book Culture book came in fifth place in the Locus Awards. But, tellingly, the one major award that Goulart actually received for a specific work (After Things Fell Apart) was the 1971 Pat Terry Award for Humour in Science Fiction from the Sidney Science Fiction Foundation. Humor was something that suffused his work and his interactions with friends throughout his life. Reviewing Goulart’s story collection Broke Down Engine: And Other Troubles with Machines in 1971, The New York Times described his work as containing “a bleak but bracing sense of humor.”

He had a sharp ear for the trappings and habits of genre and popular culture. The award that perhaps most naturally gravitated to Goulart was the broadly defined Inkpot Award for contributions to “comics, science fiction, film, television, animation and fandom services,” which was presented to him at the 1989 San Diego Comic-Con International.

Goulart was a regular guest at the NYC Paperback and Pulp Fiction Expo and other collector-oriented conventions and maintained a strong bond with his readers because he had an appreciation for the stories, characters and artifacts that had become a part of their lives. But Goulart did not just acquire a library of books; he collected tropes, images, character types, devices, twists, themes, settings and technologies and redistributed them into the reading world in the form of endlessly proliferating fictional permutations — and almost always did so with a knowing wink. For Goulart, these narrative elements and heroic icons formed a toy box that he never tired of playing in. His ability to effortlessly mix and match pieces from different genres may be why he is the only author ever to be nominated for an Edgar Award by the Mystery Writers of America on the basis of a science-fiction novel.

Fantagraphics Publisher Gary Groth, who published Goulart’s Focus on Jack Cole and edited Goulart’s contributions to the print Comics Journal, offered the following remembrance: “I got to know Ron because we both lived in Connecticut at the same time, maybe 20 minutes away from each other, and our circle of friends overlapped — oh, and our vocations as well. He was one of the triumvirate of early, autodidactic, non-academic comics historians (with Bill Blackbeard and Rick Marschall), and I published his historical writing in The Comics Journal (which I edited) and Nemo (which Rick Marschall edited) in the ’80s and ’90s. Professionally, working with him was stress-free: I could always rely on him to deliver solidly researched, well-written essays on time.

Fantagraphics Publisher Gary Groth, who published Goulart’s Focus on Jack Cole and edited Goulart’s contributions to the print Comics Journal, offered the following remembrance: “I got to know Ron because we both lived in Connecticut at the same time, maybe 20 minutes away from each other, and our circle of friends overlapped — oh, and our vocations as well. He was one of the triumvirate of early, autodidactic, non-academic comics historians (with Bill Blackbeard and Rick Marschall), and I published his historical writing in The Comics Journal (which I edited) and Nemo (which Rick Marschall edited) in the ’80s and ’90s. Professionally, working with him was stress-free: I could always rely on him to deliver solidly researched, well-written essays on time.

“When I met him, circa 1980, he was already an established professional in the SF and comics professions and I think he regarded me as an amusing upstart who was sympatico with his own slightly esoteric interests (for example, in 1986, we published a monograph he wrote on Jack Cole; no one else would have written it or published it then, but us). I never read his fiction, but his histories, many of which I did read, were always first rate. The Star Hawks strip he wrote for Gil Kane was probably the best-written adventure strip at the time; a testament to his intelligence and congeniality is that he was one of the few writers Kane worked with that Kane respected, enjoyed collaborating with and liked personally.

“Young as I was when I met Ron, he treated me as an equal and what I remember most about him personally is his humility, generosity, good-naturedness and dry wit. It is customary to refer to the dead as humble, but Ron was humble to the point of self-deprecation, so much so that I often got off the phone feeling badly that he did not hold himself in higher regard. True, he was not an A-list SF author; he was more of a journeyman, and he knew it. Our conversations were always easy going, but he made one telling comment that I haven’t forgotten. He said that he would love to be able to write high falutin’ litcrit of the kind he would read in the Journal (he was referring specifically to the criticism of Carter Scholz, who also, coincidentally, was a science-fiction novelist), but that he chose a different path — or a different path chose him. He said it with some humor but some seriousness as well, and there was an amiable acceptance in his voice that stuck with me, and maybe a tinge of regret; I’d always wanted to delve more deeply into that with him, but never found the time, of course. He was a pleasure, and I regret, as I always do, that I didn't work with him and talk to him more than I did.”

Living with his wife, Frances Sheridan Goulart (a noted author of books about nutrition), in Ridgefield, Connecticut, Goulart continued to bring pulpy early-20th-century sensibilities into the new century: the most recent book in his Groucho series, Groucho Marx, King of the Jungle was published in 2005. A collection of his mystery stories, Adam and Eve on a Raft, was released in 2001. Several new installments of his Harry Challenge series appeared between 2001 and 2012, mostly in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, with a Harry Challenge collection published in 2015. His Alex Raymond book was released in 2016. He continued to contribute comic-book scripts featuring The Phantom for the Moonstone line and, later, Hermes Press, the most recent collected in Hermes’ The Phantom: President Kennedy’s Mission in 2020.

Goulart had been ill, however, and Steve Lewis of the Mystery*File website (to which Goulart had contributed) reported the author had entered an assisted living home about a month before his death.

Goulart is survived by his wife and his two sons, Sean-Lucien and Steffan Eamon.