There’s a contradiction inherent to the mythic figure of the cowboy. As conceived in American fiction (as opposed to reality), he is an enlightening force: the long arm of white civilization reaching into the untamed lands and making them safe for more of his kind. He walks into the wilderness and makes it safe for city building. Yet, at the same time, he also represents a suspicion of the same civilization he is meant to serve. Recall that famous ‘go west’ quote, often attributed to Horace Greely: “Washington is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting and the morals are deplorable.” The mission of the cowboy is to create the conditions in which the cowboy is no longer necessary - in doing so, creating a lesser group of wimp and weakling men.

Clint Eastwood once summed up the western to author Michael Munn as “A period gone by, the pioneer, the loner operating by himself, without benefit of society. It usually has something to do with some sort of vengeance; he takes care of the vengeance himself, doesn't call the police. Like Robin Hood. It's the last masculine frontier.” You can just hear the yearning in his voice, even though he recognizes it is nothing more than a myth. Fittingly enough, his Pale Rider (1985) features an early establishing shot of the villains, a mining corporation, blasting away at rock with high-pressure hoses, technology despoiling the land (as opposed to the good old-fashioned despoiling of the land done by settlers).

Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West is utterly contemptuous of the evil businessman Morton, whose plot to build a railroad jumpstarts the plot, but it holds a degree of respect for his helper Frank, a killer of women and children. “So you found out you're not a businessman after all,” asks Charles Bronson's protagonist as the villain approaches. “Just a man,” Frank replies. “An ancient race," Bronson muses. “Other Mortons will be along, and they'll kill it off.” The end of these people, their way of life, is understood as a grand tragedy. Never mind that this way of life is all violence and bloodshed, never mind that it never truly existed. The myth matters.

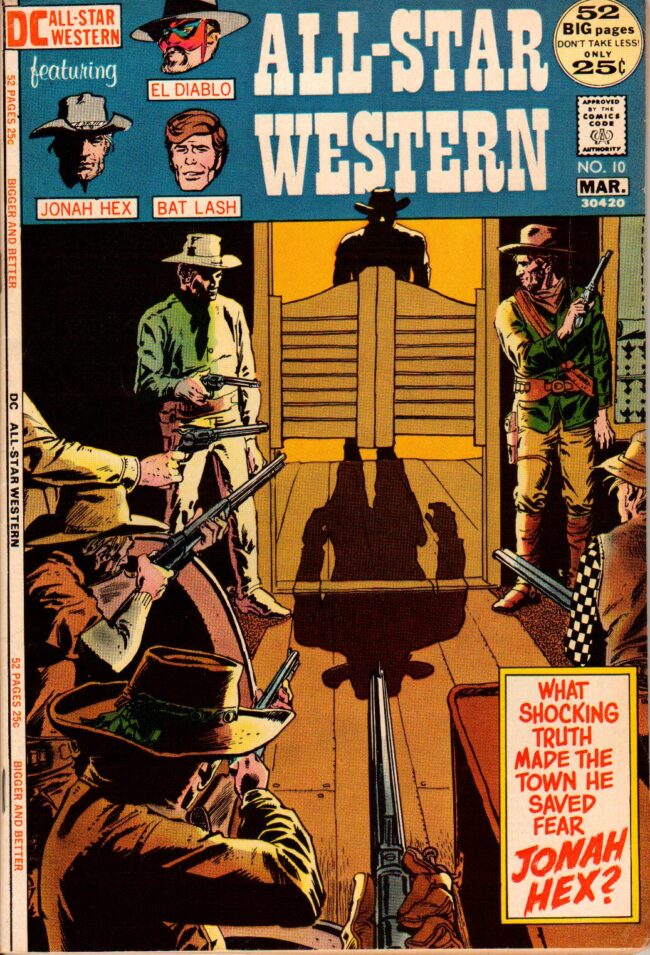

Many other westerns throughout the years -- films, TV shows, books, comics -- have tried to grapple with this contradiction and found themselves unable to square the circle. Which is why I was quite happy to put my hands on Weird Western Tales: Jonah Hex Omnibus, a collection of the character’s early adventures (before he got his own title). These original shorts, features in the anthologies All-Star Western and Weird Western Tales, gain their strength by rejecting any notion of sophistication and self-justification. As envisioned by creators John Albano and Tony DeZuniga, the scar-faced bounty hunter is a conflict-free killer. He gets a job to kill someone and he kills them. Sometimes the people doing the hiring try to betray him, and so he kills them. Rarely, very rarely, he finds a good cause – in which case he just might kill the bad people free of charge. Hex doesn’t necessarily have morals, but he has standards, and a degree of professional pride.

There’s something wonderful about the pretense-free nature of these stories. The cities are corrupt, yes, but the frontier as well. The simple, honest folk of the westward expansion are just as big a bunch of assholes as the various robbers and killers that plague them; and the biggest asshole of them all is Hex himself. A man whose hideous face hides… often equally as ugly a soul. Nothing solemn about him or the way he acts. An ugly man for an ugly world. This world is given form by DeZuniga, who said that he first envisioned the character based on an anatomical chart: "When I went to my doctor, I saw this big chart, this beautiful chart of the human anatomy... I saw the anatomy of the figure was split in half, straight from head to toe, half. Half his skeleton was there, half his nerves and muscles. That’s where I got the idea it won’t be too bad if his distortion would be half."

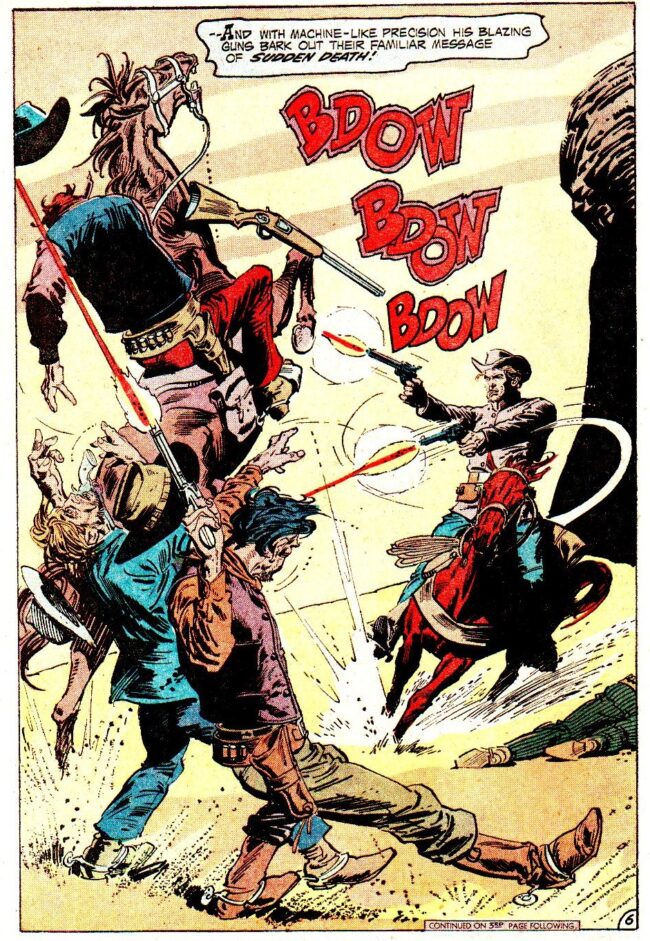

DeZuniga’s lines are strong, his geography is always clear, the characters are often centered within each panel. In the many shootouts, one is never lost as to who is shooting whom (and why they are shooting). It’s classic storytelling befitting a classic western. That many of the side characters are cliché types -- the eager young boy, the tempting woman, the evil gang leader, the cowardly sheriff -- only helps the unusual Hex stand out in the crowd. His scars are neither exaggerated nor underplayed; they are the mark of someone who shows outwardly what everyone else around him is on the inside.

DeZuniga is the main reason to read these stories, his pencils taking a fair share of not just the storytelling burden, but also of expressing the philosophy behind Jonah Hex as both a character and a concept. While he doesn’t draw a particularly large percentage of this collection, his spirit carries throughout as replacements are brought in. The great José Luis García-López feels a bit too clean when it comes to pinch hitting, his world too nice, his Jonah too pretty. Noly Panaligan, however, is probably the most successful of the substitutes – lots of big movements and dramatic poses, large crowd scenes and backgrounds full of life.

Albano, possibly understanding this (and possibly just playing along with the short story format), is content to get out the way. His stories are as plain as they come, serving up the expected excuses for one gunfight after another. His Jonah doesn’t really have a backstory – no past, nor a future. Even the Confederate background developed by later writers is nothing but a suggestion of the character design. Hex might’ve just stolen that grey coat, or it might be just a random coat that looks like a uniform a bit. If he has any ideas about the shape of these United States, Hex doesn’t share them with the readers or other characters. Actions speak louder than words, of course, and are far more exciting to look at. These Jonah Hex stories are all about the excitement.

Sadly, roughly halfway through this volume, Albano is replaced by Michael Fleischer, who is probably the writer most identified with the character to this day, carrying on from Weird Western Tales to the 92-issue Jonah Hex series, plus its 18-issue science fiction sequel Hex. From what little I've read of his work, Fleischer is an over-writer, the type who forever throws added complications to their plots, worlds and characters. It can work -- Haywire (1988-89) is one the unsung jams of mainstream American comics -- but the result can also be tiring to read.

The joy of the early Jonah Hex stories are in their simplicity and straightforwardness. Done-in-one tales of brutality, stripped down to the very essential nature of the western story formula. Fleischer attempts to build up on these foundations, not realizing that everything he adds to the character is unnecessary. His attempts to engage with ‘larger themes’ are embarrassing at best, ugly at worst, in the manner of 20th century westerns that realized that maybe what the settlers did to Native Americans is wrong, but can only come out with some mealy-mouthed ‘both sides should stop the violence.’

Under Fleischer, Hex’s Confederate military career becomes a dominating factor in the series; a long-running subplot involves a shadowy figure seeking to take revenge for something done during the war. I mean the Civil War, of course: the one in which our protagonist was on the pro-slavery side. Not that there aren’t ways to depict a protagonist who fought for a terrible cause -- about 70% of Garth Ennis’ career wouldn’t exist otherwise -- but the problem is that Fleischer doesn’t really do it well. Hex is shocked by the cruelty of southern slaveholders (despite living there for ages), and then he’s shocked by the savagery of northern troops. Both sides are thus established as equally bad, and we can move on. If you can’t engage with the moral implications of a character’s decisions, you are better off avoiding them.

Again, what worked in the earlier shorts was that all of these ideas simmered beneath the surface, expressed mainly through the artwork and the sheer man-is-wolf-to-man brutality of the setting. By bringing it out into the light, Fleischer reveals the exact same set of problems as other westerns – trying to both celebrate the manliness of his protagonist, while engaging cerebrally in what he has done. So, Hex fought for a terrible cause (and continues to carry that emblem), but he fought for it well, which should be commendable because... reasons. Manly reasons.

The people hunting down Hex throughout Fleischer’s stories are themselves all ex—Confederates. It’s important to the story to let us know that Hex never truly betrayed them; they are after him due to a misunderstanding, which is pretty odd for a character who was presented earlier as a kind of scoundrel who had personal code of honor (rather than national one). This is faux depth, mistaking backstory for the actual psychology of a character: Fleisher adds more and more history to Hex, but none of it makes him more compelling (call it “The Wolverine Effect” if you will), nor does it better explain his actions throughout past and future tales.

Likewise, Fleischer’s treatment of Native American characters suffers from exactly the same type of ‘both sides-ism’ – in which the whites might have struck the first blows, but rough elements within Native tribes keep resisting an offer of peace. An offer mediated by Jonah Hex, of course, the one white man the Natives can trust because he’s just that tough and noble an hombre. Richard Slotkin’s Gunfighter Nation, one of the best books one can read about American pop culture, recognizes this recurring character type as ‘the man who knows Indians’, an American architype going back to days of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales: “As the 'man who knows Indians,' the frontier hero stands between the opposed worlds of savagery and civilization, acting sometimes as mediator or interpreter between races and cultures but more often as civilization’s most effective instrument against savagery—a man who knows how to think and fight like an Indian, to turn their own methods against them.”

Hex’s own empathy with the Native Americans in these stories can only extend so far. They are human now, instead of thoughtless monsters to be slain by white heroes, but are forever seen through the prism of victimhood (of their own savagery, rather than the settlers’ violence). Hex becomes just another Jimmy Stewart figure (think Delmer Daves’ Broken Arrow), a radical guise over reactionary ideas.

In The American Monomyth, Robert Jewett and John Shelton Lawrence spend quite a lot of time on the figure of the cowboy in popular cinema, and the way it’s been echoed through the years under different guises: the tough cops who care about results (not regulations); the vigilante killers who step up where the system fails (because cops aren’t violent enough); and (of course) the superheroes. All of them poured in the same mold, all of them carrying the inherent self-contradicting nature of the cowboy. In order to defend civilization, you must reject the very things (rules, regulation, civil discourse) that make it into a civilization. This is a circle that cannot be squared, and is thus endless in its acceleration, the threats becoming more dire and justifying more extreme action from the protagonists.

The inevitable conclusion, that maybe ‘civilization’ isn’t peaceful, and that violence is a calculated part of its existence, is never quite reached. Fleischer’s stories are always on the precipice of something deeper, without ever taking the dive. Maybe it’s unfair to expect Fleischer to succeed where so many others tried and failed (especially considering the limitations imposed on monthly comics); maybe it's best to simply enjoy the comics as an endless parade of shoot-y violence - one cannot deny that these stories almost always look good.

Albano made it work by recognizing the limitations of both genre and form; the early stories cut away from all the clutter until only the essential formula was left. It might not have been an ideal road toward a long-running series, but it was fantastic as long it lasted. By attempting to break out of these limitations, Fleischer made the Jonah Hex character into what it is today: undoubtedly a success story in terms of American comics -- how many other western heroes you can name in the American market? -- but lacking the purity of Albano’s tales. Fleischer’s Hex is the one everybody knows, quite likely because it is exactly so familiar and comforting a version of the Western hero – telling the readers the story they want to hear, rather when what they ought to hear.

* * *

Front page detail from Weird Western Tales #19 (Sept./Oct. 1973), pencils & inks by Luis Dominguez.