Mark Newgarden, the co-author of the forthcoming How to Read Nancy, chatted with the editors of the new book, To Laugh That We May Not Weep: The Life and Art of Art Young. Their discussion follows below. -The Editors

My introduction to Glenn Bray was as a 13-year-old cartoon nut, eagerly stuffing an envelope addressed to Sylmar, California with one dollar cash for GJDRKZLXCBWQ COMICS (the beloved all-Wolverton digest —which I still own to this day, complete with original spiffy mailing envelope.)

Glenn, can you give us some background on your journey as a collector, curator and editor and the ever-refining aesthetic that has guided you?

Glenn: I think that almost everything I’m attracted to visually, leads right back to Kurtzman’s Mad.

I’m very happy with the interview within the book on my collection, The Blighted Eye, also published by Fantagraphics Books (plug!) It was through Doug Harvey’s endless nagging that I pinpointed my obsession with printed matter —when I was about 5 years old, seeing a Kellogg’s giveaway booklet illustrated by Vernon Grant. The bells went off in my eyes; the work was SO personal, lively and colorful, it hit me more than any music did at the time.

Growing up in a small suburb, I had a great friend who, like me, also had a hoard of old comics. We riffed on each other’s knowledge and likes/dislikes, so the seeds of seeking “good” materials was planted early on. My mom urged me to read ANYTHING rather than sit in front of the TV, and comic books were a part of the house (we had subscriptions to both Little Lulu and Donald Duck comics.). Then by chance, some neighborhood kid offered to trade me his 2 binders full of a complete run of Mad comics. This was probably about 1956 and I was 8 years old. It was the Kurtzman “Hey Look!” pages and Basil Wolverton’s “Mad Reader” that shook me to my core. That was a real hit, and I’ve been “chasing the dragon” ever since.

When and how did you first encounter Art Young’s work —and where does it fall for you on that aesthetic spectrum?

I bought a copy of Art Young’s Inferno at one of the large book fairs out in LA in the mid-1990s. Looking back earlier, I already had reference books that had maybe one Art Young image in them. But seeing just one drawing didn’t jumpstart my interest.

When the internet came around and booksellers were just an email away, I started locating more Art Young. Around 2003 I saw that Argosy Bookstore had an original on their website, but it was a political one. I wanted those damned DEVILS! I kept after the person in charge of the art department until they stumbled upon materials in the warehouse they had completely forgotten about. So, weirdly, I became more interested in Art Young via his original artwork, rather than the printed page. This was the complete opposite of how I saw and collected Basil Wolverton, Carl Barks, Harvey Kurtzman etc.

When the internet came around and booksellers were just an email away, I started locating more Art Young. Around 2003 I saw that Argosy Bookstore had an original on their website, but it was a political one. I wanted those damned DEVILS! I kept after the person in charge of the art department until they stumbled upon materials in the warehouse they had completely forgotten about. So, weirdly, I became more interested in Art Young via his original artwork, rather than the printed page. This was the complete opposite of how I saw and collected Basil Wolverton, Carl Barks, Harvey Kurtzman etc.

My collecting journey led me to get up close and personal with my comic book idols…and I got to meet and work with those three comic book legends. Art Young was dead 5 years when I was born. I regret not having the chance to meet him. I consider Young to be the Harvey Kurtzman 50 years before Kurtzman was. Both started with the “QUESTION AUTHORITY” attitude, which I subscribe to.

What was it about Young’s work that set him apart from his numerous contemporaries?

Glenn: It took me awhile to really understand how “modern” his style was. I’ve recently been researching old New Yorker magazines (1925-1940), and found that Young was rarely used. His work was “out of sync” with what the editor considered at the time to be “chic” and contemporary. For my money, Art Young is one of the most gifted graphic artists ever to hold a pen. Name anyone else that can draw hands or trees as well!

We were having a brunch get-together with Drew and Kathy Friedman awhile back, when I was still submerged in working on the Young book. Drew kept asking me what was so great about Young. I told him I now thought he was as important as Robert Crumb, and in his time was just as relevant and conscious as Crumb was. I got that steely-eyed Drew stare you never want to be on the receiving end of.

I’ve known (and actively avoided) that stare for over 35 years now!

Frank, your concentration has been in the field of comic books: as a writer, editor and scholar. But you’ve also written extensively on newspaper strips and Hollywood animation, especially on the work of Fred “Tex” Avery (and in my estimation, you are the absolute go-to guy on everything John Stanley.) Can you tell us a little bit about how you became interested in Young and involved in this ambitious project?

Frank Young: Art Young was on that list in my head called “Great Cartoonists Whom I Admire, Based on Two or Three Images I Keep Seeing Over and Over Again.” I saw these images in older books about comics history, poorly reproduced but visible enough to give me the idea that this fellow was important. I also aligned him with Harvey Kurtzman. There’s a similar life in their ink lines. But as with so many towering figures in an ignored art form, there wasn’t any Art Young to pore over as I developed my critical and thematic eye towards comics.

In the 1990s and 2000s, I served my infamous term as managing ed on The Comics Journal, begun comics scholarship blogs, and came into contact with some great people. My work on John Stanley led me to meet Art Spiegelman, Michael Barrier, Glenn Bray and you, to name a few. While David Lasky and I worked on our graphic novel The Carter Family: Don’t Forget This Song, Spiegelman invited me to be on the board of advisors of The Toon Treasury of Classic Children’s Comics. My involvement in that project led to many good things.

Visiting the home/museum of Glenn Bray and Lena Zwalve in summer 2013, through our mutual friend Carol Lay, was a religious experience. The first thing Glenn showed me was the original art for the cover of Mad #11. From there on, it was a staggering tour of his extensive collection of original art, comics, artwork, books, etc. I wonder if Carol realized how much of an impact this visit would have on my life...this kid was in the candy store by which all candy stores are judged. I flashed back to my one visit to Bill Blackbeard's chaotic den in San Francisco. Glenn's collection is organized, curated and attractively presented. From bound volumes of 1940s comics to impeccably stored originals to shelves of work by cartoonists familiar and unknown to me, this is the best hoard of significant comics work I've yet encountered.

Despite this overwhelm, my eye kept going to some gorgeous wash drawings, framed on the wall--images from Art Young's 1927 book Trees at Night. Once I indicated interest in Young's work, Glenn showed me about 100 pieces from his large collection of originals. As we pored over these drawings, with their masterful control of pen, brush, conte crayon and wash, the message of Young's work struck me. It wasn't only about the artwork. This work was alive and relevant. I had to keep reminding myself that most of these pieces were approaching 100 years old. This sudden exposure to a sleeping giant was powerful. I wanted to see all his work, and know who he was. This was cartooning and illustration I connected to in a major way.

I especially liked his work of the 1930s, which resembles Harvey Kurtzman's 1950s work in its linear energy. But all of it--even the more formal and ornate work of the late 19th century--had an effect on me. "There needs to be a book of these," I said, many times that afternoon. Glenn and I kept in touch, and talked further about the idea of doing a book on Young. We pitched it, and ultimately, Fantagraphics went for it.

Meanwhile, Glenn loaned me copies of Art Young's two volumes of memoirs and musing, On My Way and His Life And Times, plus his '30s masterpiece, Art Young's Inferno. Since I was to write the centerpiece of the book--a biographical essay that would offer the reader a road map to the book's contents, and an understanding of the artist--I studied up on Young's life and pored over his work, and hoped to connect the work and the creator in a meaningful way.

Who was Art Young? (As a 20th century political artist and as a voice of conscience?)

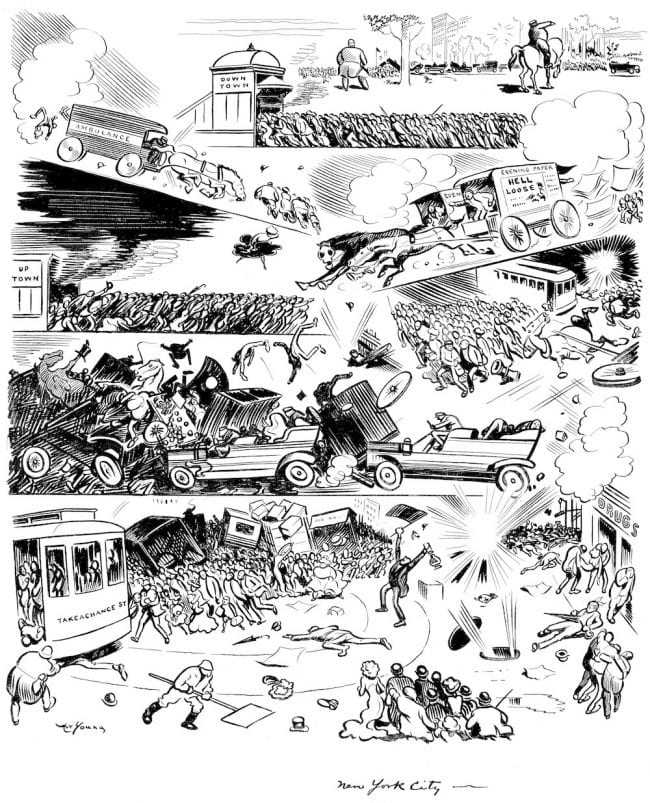

Frank: Art Young is a prime example of the gentle but powerful voice sometimes seen in American media. He never raises his voice to the shout level we’re used to in 2017 mass media. He makes his points persuasively but allows the viewer to draw their own conclusion. Young’s cartoons always ask: how do you feel about this?

Whether the viewer agrees or not, they have been presented with his viewpoint in the least rancorous way. When he has a harder edge to his presentation (“Holy Trinity,” “Having Their Fling” and the cartoons from 1934’s Inferno) there is always a sense of the human comedy, and of careful consideration of the entire issue—not an impulsive blurt, as we’re used to via the thing that calls itself “president” and the sound-bites that batter our souls every day.

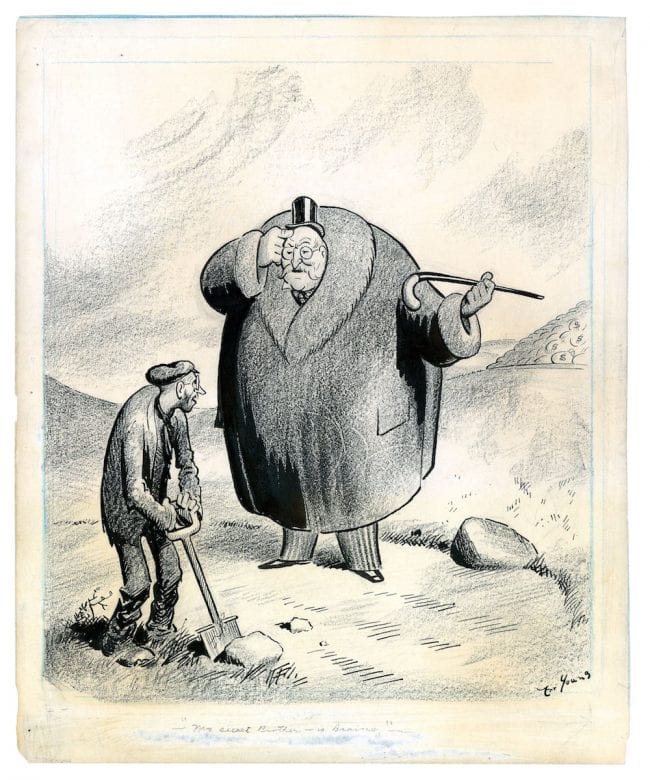

His villainous figures are deluded and misled, but they’re seldom outright monsters. We can still laugh at their buffoonery. I think of that cartoon with the caption, “My secret, brother, is brains!” (p. 111 of the book) The grotesquerie of that over-stuffed plutocrat—who anticipates the distended animals in Tex Avery’s King-Size Canary—is laughable, but the foibles behind that gluttonous frame show the tiniest hint of fondness in Young’s eyes. Tsk, tsk, he seems to say; there but for fortune and good sense.

What discoveries did you make as you researched your subject?

Frank: I never fully understood the patriotic and xenophobic hysteria that hit World War I-era America until I researched the details of Art Young’s trials. The accounts of intense xenophobia and the rhapsodic propaganda seemed familiar. I was reminded of the fever-pitch of anti-Middle East sentiment that sprang up after 9/11, and of Trump’s trumpeting about the proposed wall at the Mexican border. The most powerful lesson, overall, was my understanding that history seems doomed to repeat itself in America. Our people and politicians make the same bad choices, with the same bad effects, and it seems no lesson is ever learned. That is why so many of Art Young’s cartoons could be run on today’s op-ed page of the newspaper (assuming any papers still exist with the guts to print his work).

I can't think of another American cartoonist who was tried for sedition. Can you give us some background?

Frank: Young's legal troubles began in 1913 when he and The Masses co-founder Max Eastman brought attention to the fact that the Associated Press was suppressing or downplaying news about a violent labor strike at a West Virginia coal mine. The AP charged Young and Eastman with libel twice. The case was dismissed when it was obvious that their observations were true.

An editorial written in reaction to the first trial sparked a second libel suit from the AP. When Young and Eastman's lawyer threatened a The Masses expose of the AP's practices, that suit was quietly dropped.

Young and Eastman returned to their normal lives. By 1916, America's isolationist stance towards the first World War seemed on shaky ground. Woodrow Wilson got elected on his promises that he would keep America out of the war. Three weeks into his presidency, Wilson declared war on Germany. America went slightly mad with xenophobia and a frenzy of patriotism.

Young's response was his infamous cartoon "Having Their Fling," in which he shows what, in his heart, the war was really about. The Masses was already suffering; some issues were suppressed from mail distribution, as they were in violation of the 1917 Espionage Act.

One month after "Having Their Fling" appeared in The Masses, Young, Eastman and other employees were charged with "conspiracy to obstruct the recruiting and enlistment service of the US" under the Espionage Act, due to the publication of "seditious articles cartoons and poems.” If convicted, they would receive 20-year sentences and fines of up to $10,000 each.

Young and Eastman went through two court trials in 1918. Each time, a hung jury resulted in a mistrial. Though Young was never again charged, he exited the trials shaken and with his professional reputation damaged. Former clients wouldn't hire him. People he considered friends now shunned him. He would eventually shake off his pariah status, but the trials took a toll.

A final question: the timing for To Laugh That We May Not Weep could probably not be better. What is it about Art Young’s work that resonates today?

A final question: the timing for To Laugh That We May Not Weep could probably not be better. What is it about Art Young’s work that resonates today?

Frank: Art Young’s humanity—the soul of kindness—offers us a sense of hope as it acknowledges the train-wreck around us. 2017 has been a nightmarish year, but a study of Art Young’s work reassures us that America has been through similar horrors and survived. While there is an understandable lessening of hope compared to, say, the days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, there is still hope. To realize that hope, we must be more humane beings. We must step back from corporatization, mindless consumption, greed and the hard shell we put around ourselves and be decent, caring individuals.

Art Young shows us one way to speak up without ranting or foaming at the mouth. Most of us experience political discourse via rants and ravings on Facebook, which may turn out to be the worst possible forum for such a discussion. Instead of shouting matches or physical conflicts, I wish the antifa protesters would paper buildings with blow-ups of Art Young cartoons--or create new work inspired by Young’s voice. (These images are in the public domain, gang, so go for it!)

It’s a tall order, and I hope younger Americans can rise to the occasion. The voice and artistry of Art Young can help us remember to keep a sense of perspective, and that to flippantly villainize a person or agenda isn’t enough. We need to take a deeper look and find a humane voice in our response.

Glenn: I advise you to:

- Look at the cover and title.

- See the double spread of “In A World Of Plenty”

- Read the essay by Art Spiegelman.

If you don’t “get it” by then, you are probably a Trump-kin.