Open a Paris door and you never know what you'll find. One in the Latin Quarter, for example, hides a mini-Pompeii of caricature. That its images survived at all is a shock. But far more startling are the names they link: Oscar Wilde, Emile Zola, Édouard Manet… Tom & Jerry.

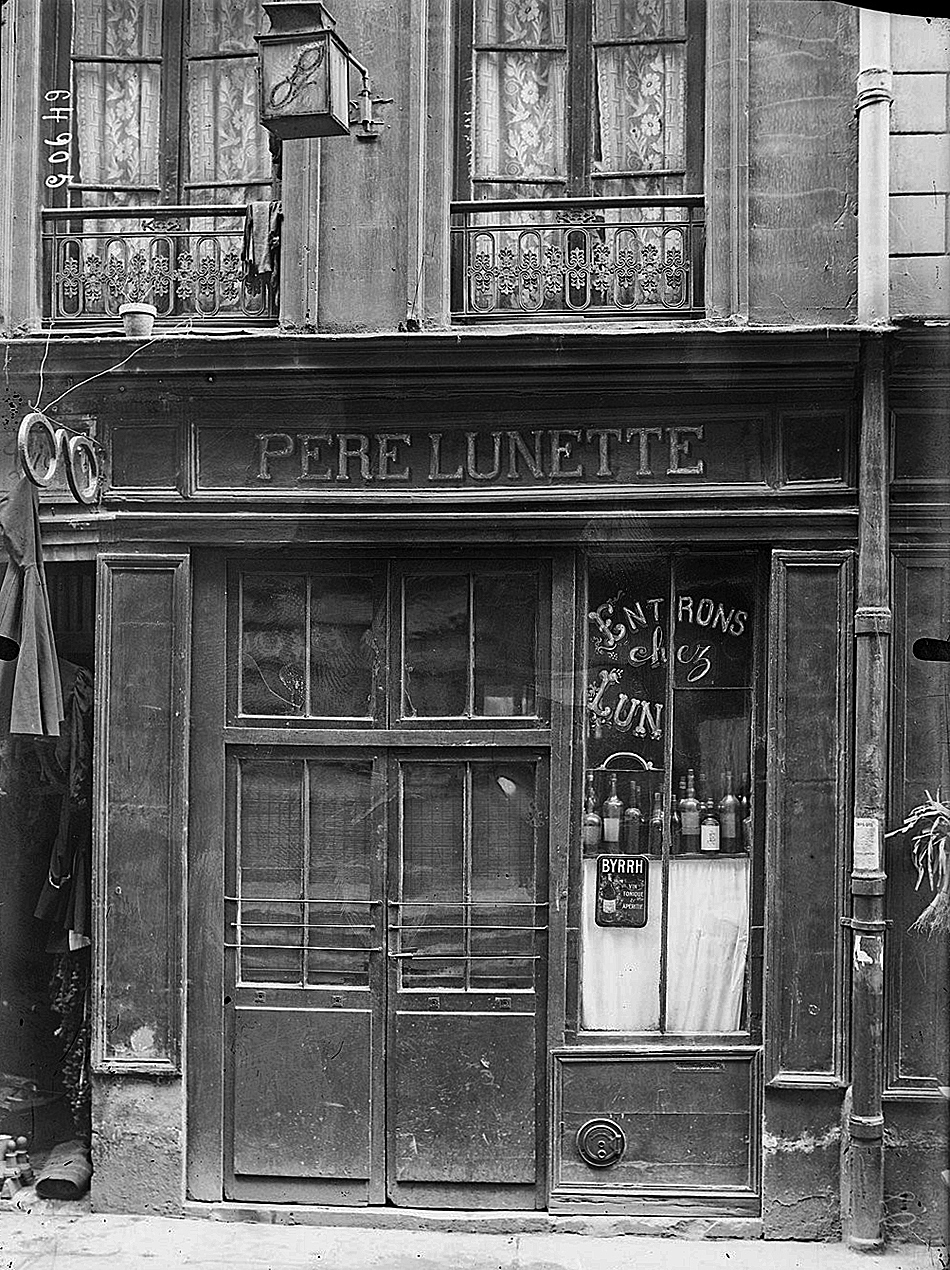

Between 1840 and 1908, this little spot was a bar called Père Lunette. Père Lunette was a bouge, a dive where locals went to get hammered. It was just one of hundreds but, as journalist Louis Barron wrote in 1883, "Its originality is that it is illustrated."

In fact, the bar had a second originality. For Louis Barron was not just a journalist. He defected from the Army to revolution and, in 1871, fought for the Paris Commune. This saw him deported for six years to an island 16,000 miles from France. There, in the Pacific Ocean, he and his fellow prisoners cobbled together a comic journal. They baptized it "The Illustrated Parisian" (Le Parisien illustré).

Such was the secret life inside Père Lunette: comic art born of militant politics. For, although the bar served society's lowest, it also welcomed socialists, anarchists and Communards. Outsiders drew its cartoons and radicals featured in them. "Become righteous, O politicians," joked a columnist, "and you too can win a place in Père Lunette's rogues' gallery." Père Lunette watched caricature evolve and it witnessed the art's most troubled hours. Its art personifies laughter as resistance.

Père Lunette's building arose in 1839, a watershed moment in satirical history. Via papers like La Caricature and Le Charivari, comic art had muscled its way into political life. Art was also important to its architect, an entrepreneur called Antoine Vivenel (1799-1862). Vivenel, who collected Old Master prints, gave his rural birthplace its own museum. The bar in his new building opened circa 1840, under a boss by the name of Lefèvre. Lefèvre's round glasses saw him nicknamed "Père Lunette" ("Daddy Spectacles") and his pince-nez became the bar's insignia.

Many Paris bars had painted walls; murals at the nearby Château Rouge starred a guillotine. But Père Lunette was different because all its art was satirical. If most of these visual jests are long gone, many descriptions of them remain. The cartoons featured left-wing politicians, writers and celebrities depicted as animals, ogling nudes or (in the case of one Alfred Naquet) waving scissors. It was Naquet – drawn with his feet on a heart – who, in 1884, legalized divorce.

Laughter was critical to those who drank here. The bar's initial regulars were chiffoniers, rag-and-bone men who scavenged through the garbage with sticks. During the 19th century, as Antoine Compagnon has written, Paris was "a kingdom of re-use, recycling and reselling." Everything was trafficked, from old clothes and bones to the table scraps from cafés. Prowling in the dark for such assets was abject. But, at the time of Père Lunette's opening, artists saw chiffoniers as "philosophers" – night owl bohemians with independent minds. The idea appears in work by C. J. Traviès, Honoré Daumier and Charles Baudelaire.

This Paris was a world in which everything had its price. Via prostitution and dissection, that included human bodies. As "public women" grew more and more ubiquitous, Père Lunette happily served prostitutes.

Nineteenth century prostitution had countless names. According to their class, working girls were "lolottes", "cocottes", "grisettes", "lorettes" and "nanas". During the 1840s, Père Lunette's clientele included grisettes, the calculating young girls mocked by Henry Monnier (1799-1877) in "The Grisettes" and "Grisettes in Hell". In 1853, painter Charles Jacques was struck by the youth of prostitutes around the bar. Almost all, he told Edmond de Goncourt, were "dykes (gouines) between 11 and 16."

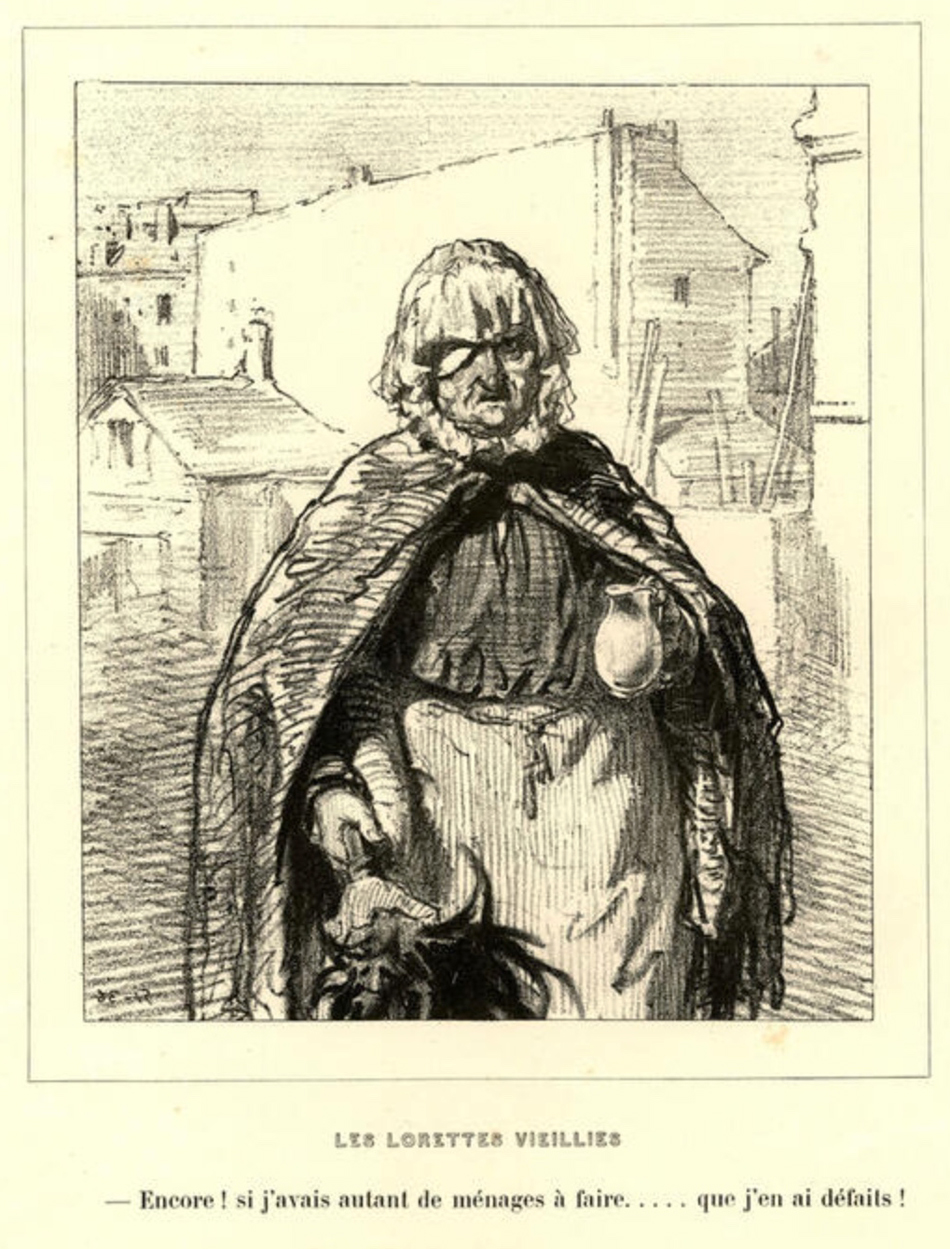

Prostitutes and chiffoniers had their own cartoonist: Sulpice Guillaume Chevalier (1804-1866). Chevalier, who signed his work "Paul Gavarni", showed the lorettes' transgressions were not only sexual; they also liked rude speech, drink and cigars. Twenty years after his death, prostitutes remained prime customers at Père Lunette and, by then, the goodtime girls were long in the tooth. Yet they weren't viewed as ruins. They were seen as characters out of Gavarni's The Whores Grow Old.

Although Père Lunette was notorious, anyone could drink there. Once you opened the door, you found a crowded bar that faced a narrow bench of imbibers. A fence topped by glass created a longer room in back. This was known as "the Senate" and reserved for regulars. Here, says 19th century specialist Jean-Didier Wagneur, "The walls were totally covered in cartoons and caricatures."

Even the bar's regulars appeared on its walls, but their images too were political. An aged regular called "Diogenes", for instance, was depicted with a ragpicker's lamp and stick. That Diogenes who drank in the bar lit streetlights. But, because of the ragmens' role as "philosophers", the name Diogenes was slang for 'chiffonier'. The cartoon's caption, This lantern's bound to earn less than Rochefort's!, poked fun at a radical weekly called La Lanterne.

Everyone who wrote about Père Lunette mentions its smell. One policeman called it "a mixture of bad breath and rotgut fumes… combined with acrid smoke from the pipes in every mouth." This fog, claimed Louis Barron, made it hard to see. But to him the drawings were "delicious… the utterly frank naturalism of the miserable."

Père Lunette's neighborhood was certainly miserable. The bar sat in "La Maube", on the edge of the Latin Quarter. Its name derived from a market center, the Place Maubert, which is still there today.1 But the stalls which once sold scrap metal and skeleton keys now sell fancy cheese and fancier wine. Long gone are La Maube's mégotiers, who dealt in tobacco pried from cigarette butts.

Père Lunette's street, the rue des Anglais, dates from the 12th century. It was shortened twice, but the stub that remained could never be reformed. It stayed, as playwright Oscar Méténier wrote, "narrow, filthy, stinking and dark." The minute night falls, he adds, "an army in tatters arrives, a human flood of harlots, ragmen and ruffians … The street becomes a mass that heaves in the darkness… yapping, screaming, arguing and crying foul."

These were Père Lunette's art-loving regulars. Their dive of choice tallies 300 square feet which one report describes as "a hallway" (another, "an intestine"). Le Figaro's Albert Wolff said it was "like trying to drink in an omnibus." In 1895, American war reporter Richard Harding Davis griped that Père Lunette was "very small to enjoy so widespread a reputation."

But the bar intrigued crime writer George Grigson. Its back room, he wrote, "is what Père Lunette refers to as its 'museum'. Those caricatures inside are less repellent in their execution than in their pornography." A woman Grigson met claimed she helped paint them. ("At one point she worked for the illustrated weeklies. But these days she trades all her art for absinthe… her hand can barely trace those drawings used to settle her tab.")

More than one journalist met the same woman. Three years later, Albert Wolff reports that she is "still young, with curly hair and… an interesting face." She also turns up in Pío Baroja's novel Los Últimos Románticos ("The Last Romantics", 1908). One of its characters takes his friends to "Padre Lunette", where they learn that much of its art came "from a female hand."

Drunks – men, women and children – were endemic to La Maube and anyone who knew the area knew them. This was the case with habitué Alfred Delvau (1825-1867), a left-wing writer and lexicographer. In 1864, Delvau characterized Place Maubert as "a human swamp." By that time, however, Baron Haussmann was redesigning Paris and those who needed work poured in from rural France. One of these ex-provincials was Emile Zola, who lived two blocks away from the bar. Zola was 20 and, like countless others, struggling to pay the rent on a garni. Garnis were shabby, semi-furnished rooms, crammed into some of Paris' oldest buildings.

The garnis around La Maube were grimmer than its bars. Thus, for a newcomer, bars were a better place to while away the nights. They were known as "débits de consolation", "consolation" being slang for their eau-de-vie (cheap brandy). Between 1854 and 1900, per capita intake of such hard liquor soared, rising from 1.5 to 4.5 liters a year. But, until World War I, the term "alcohol" (alcools) applied only to distilled liquors – not boissons hygiéniques ("healthy drinks") such as wine, beer and cider. When it came to total alcohol consumption, by 1900 that was 17 liters per person per year.

A similar separation applied to drunkenness (ivresse). People who were tipsy on wine displayed an "ivresse gaie et bon enfant": intoxication that was gay and "well-mannered". But, especially when it came to the working class, getting sloshed on spirits produced an "ivresse lourde et imfâme": a base, repugnant stupor.

There were many terms for a bar like Père Lunette, tags that signalled its ambiance. A "caboulot" was a low joint filled with posers and a "bastringue" one that offered music. A "taudis" was a shack and a "tapis franc" served criminals. Newspapers used the catchall term "cabaret" but humble folk called their locals "bousingots" and "bibines". 2 The poorest clients drank shots known as tord-boyaux ("innard twisters") or casse-poitrines ("chest crushers"). In a charcoal scrawl on its wall, Père Lunette warned that all drinks came "without government warranty." Clients obeyed the bar's painted rule "PAY WHEN YOU'RE SERVED."

This may seem like an unpromising source for art. Yet nothing, as it happens, is further from the truth. Not only was the bar's "museum" famous. Its community also played roles in Édouard Manet's painting Olympia and Zola's L'Assommoir – each a landmark work that modernized its medium.

The bar's art apotheosis, however, was political. During 1870, in just six months, France declared and lost a war with Prussia. For two-thirds of that time Paris was besieged, severed completely from the outside world. Officially, the country was now a Republic, but its government fled the capital for Bordeaux. Most of Paris' well-off residents followed, with workers and the poor left to starve and freeze alone. After the Siege there were new elections, but the majority they returned was royalist. The hungry, destitute capital became enraged. On March 18, 1871, Paris declared herself an independent Commune.

There was now a younger "Père" at Père Lunette. He was Pierre-Louis Berry, 29, and he kept his bar open through the Siege. (Thanks to the capital's huge reserve cellars, starving Parisians never lacked for drink.) As with every drinking spot, government spies kept tabs on him. But, as the Siege progressed, such efforts flagged and militant meetings sprang up in places like Père Lunette. "We're going to settle every score with the bourgeoisie!" cried a typical speaker. "In life they never wanted community… Now we'll have it …WE'LL DIE TOGETHER!"

The Prussian blockade of goods crippled the comic press, so Siege cartoons could only appear on single sheets. Publishers made these into "series", issuing them day-by-day and sometimes hour-by-hour. The cartoon mania this engendered was surreal, with drawings hung on ropes along the streets, stuck on walls and even pasted over windows. Artists worked in teams, cranking out "Actualités" ("Newsflashes").

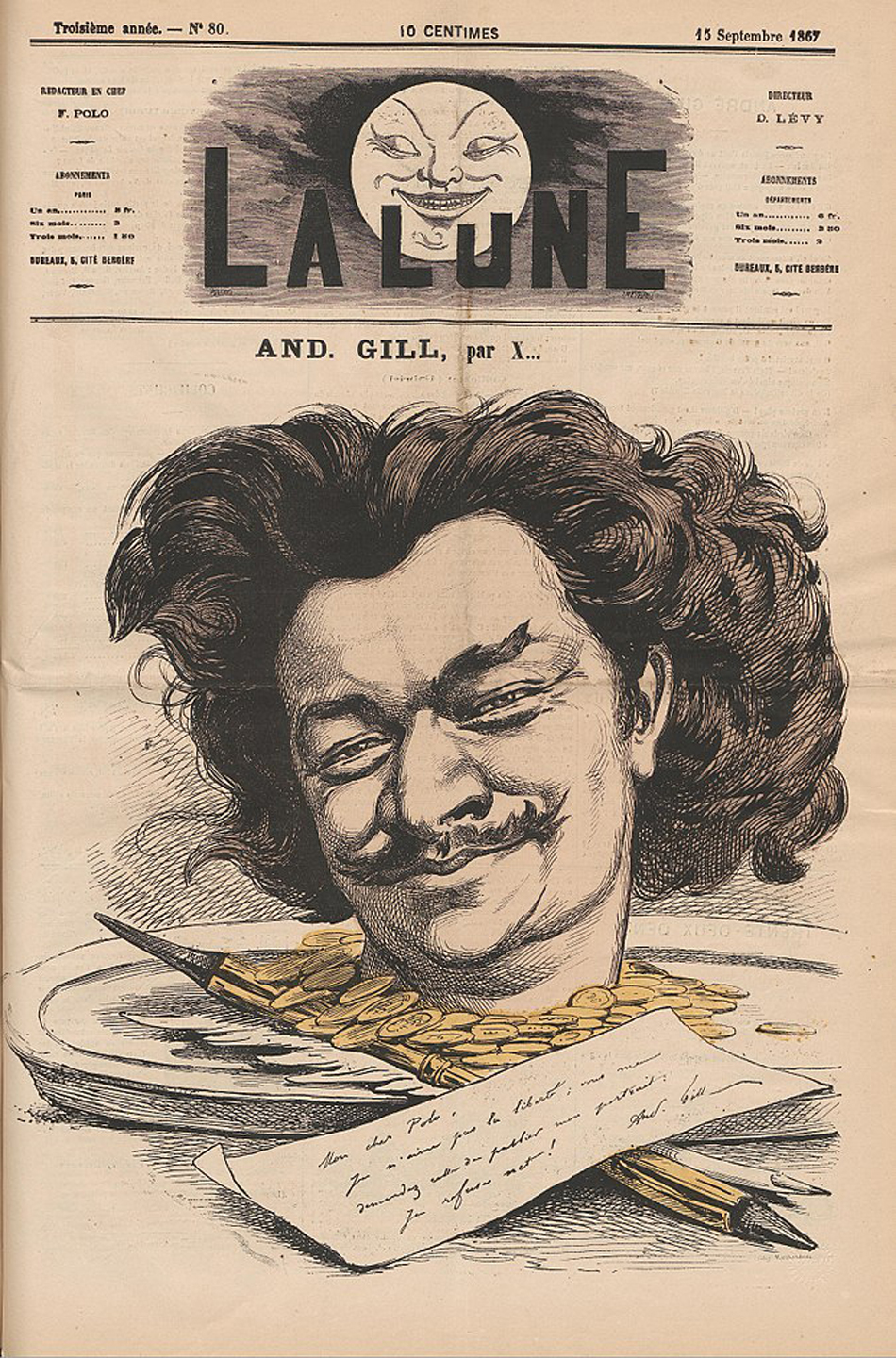

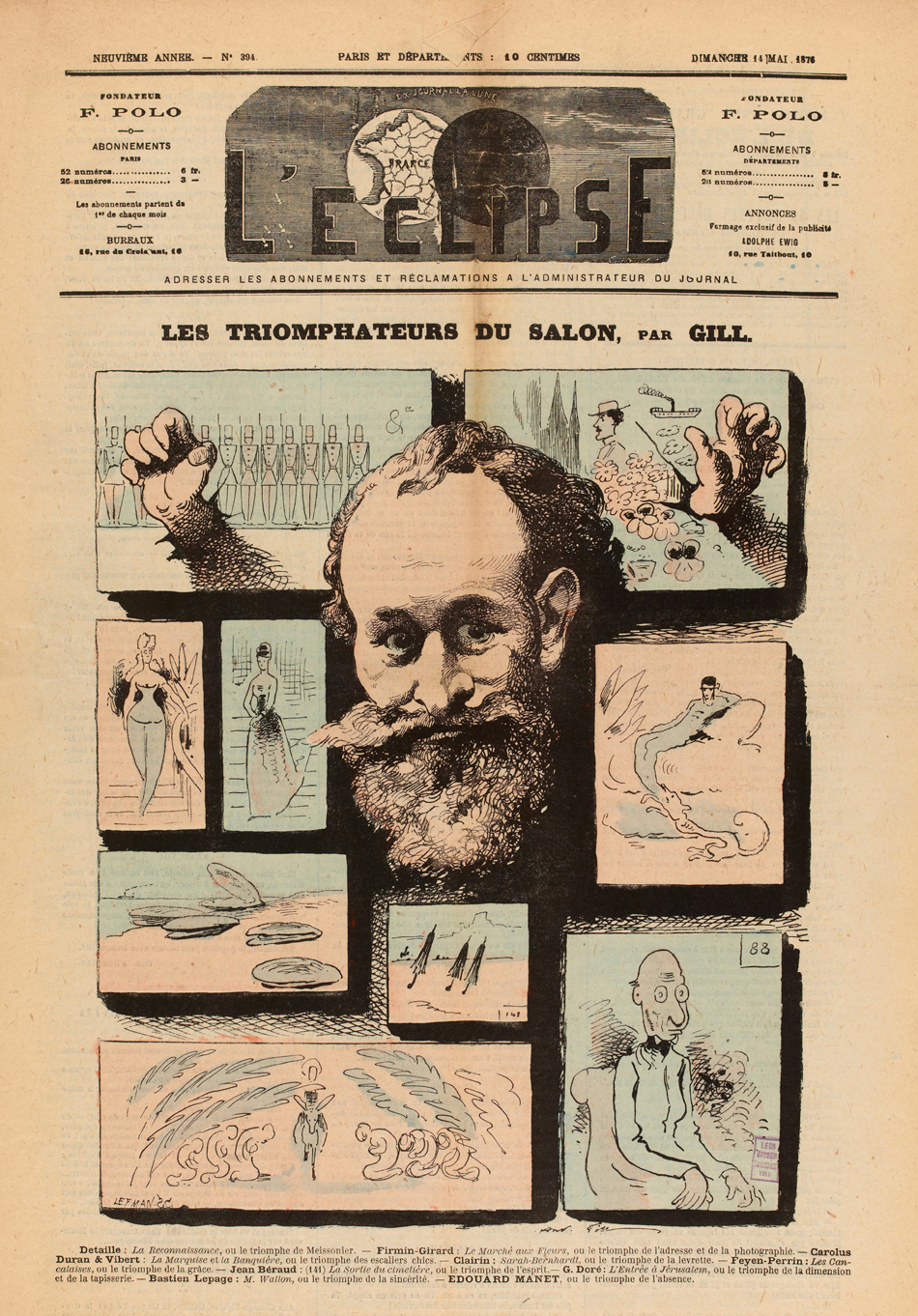

A few cartoonists tried to relaunch their papers, one of the most prominent being André Gill (Louis-Alexandre Gosset de Guînes, 1840-1885). The kind of celebrity Parisians knew in the street, Gill both lived and worked in the Latin Quarter. He held court at Au Tonneau, two blocks from Père Lunette.

Gill could not revive his weekly. But, steps away from the bar, the artist M. E. Rosambeau launched one called La Flêche ("The Arrow"). Three other comic journals – Le Charivari, Georges Pilotell's La Caricature politique and Le fils du Père Duchêne – appeared sporadically. As the Siege worsened, all the satire grew more savage. In reaction, on March 11, 1871, Pilotell's paper was banned, as were any further comic publications.

This return to censorship helped launch the Commune. Eleven weeks into it, the French government forces attacked their fellow citizens. They bombarded Paris, then invaded her – and they murdered thousands in the streets. Commanders ordered kangaroo courts, passed summary sentences, then held executions. (On Place Maubert, three hundred people were "tried" in a café and shot.) Between May 21 and May 28, there were 17,000 "official" deaths. But thousands more were slain – no one really knows how many – and thousands were deported. Setting the city ablaze as they fled, the Communards destroyed and damaged many landmarks.

Nothing in civic life escaped the outcome. For eight years, the government abandoned Paris for Versailles (until 1977, Paris was even denied a mayor). Censorship was reinstated and pro-Commune images banned, causing the loss of countless caricatures and cartoons.

But Père Lunette refused to disown its rebel art. One of its most beloved caricatures, for instance, was of feisty Communard Louise Michel. This militant feminist (now deported) was popular in the bar. During the Siege, one of the regulars helped her raise medical funds. The man in question, says Michel's biographer, was "six feet tall and strong as a horse". He may have been the Communard Jean Allemande, a typesetter who – with his mother – ran a nearby bouge.

Nine years later, after an amnesty, Louise Michel returned. At the head of an anarchist march, she was arrested again – in Place Maubert. She had ordered marchers to loot the bakeries, crying "Don't just demand bread, break in and take it!"

Cartooning boomed around Père Lunette. Its neighborhood was home to many printers (a trade notorious for the way employees drank). Most of these firms produced generic forms and texts. But Louis Jossu, across from the bar, specialized in "Death Notices" (advertised on the building). Other printer neighbours were Paul Eugène Lanoüe, Jean-Baptiste Bulla and François-Desiré Gosselin. Lanoüe sold theatrical cartoons, including those by Étienne Carjat. Bulla, too, made comic prints – from classics like J.J. Grandville's Métamorphoses du Jour (1854) and Cham's Cours de Hygiene (1862). Cartoons printed by Gosselin, a lifelong socialist, helped launch 1848's Revolution.

Closest to the bar were printers of opposing politics. Théodore Moronval's anti-Communard cartoons came from his "Dépôt Central de l'Imagerie Populaire" ("Central Registry of Working-Class Visions"). But radical Jean-Marie Grognet, 36, made a name out of Actualités. His cartoonist Farolet drank at Père Lunette and became a star of its "museum". Farolet's signature remains on the wall.

Another bar regular was Alexandre Dupendant. Dupendant, 38, worked as a lithographer. But he was better known as a local bohemian, an ardent Communard and a cartoonist. He survived the murderous purge but refused to flee his Quarter. At the age of 51, that was where he died.

The Commune left Paris littered with burnt-out buildings, unburied bodies and unruly graphic art. Returning residents blamed this all on the working class and, specifically, on their love of drink. They saw cartoonists and Communards as "apostles of absinthe", filled with low-rent booze and class hatred. Their women were pigeonholed as "petroleuses", fictive pyromaniacs blamed for setting the city alight.

Much of this propaganda spread through print. Along with graphics of the ravaged city, anti-Communard cartoons replaced Actualités. They included best-sellers like Cham's "Follies of the Commune" (Les Folies de la Commune), Bertall's "Those Communards" (Les Communeux), Henri Demare's Communardia and Dubois' "Paris Under the Commune" (Paris sous la Commune). All hammered home that the Communards were losers, big names only in little bars like Père Lunette.

Emile Zola, however, disagreed. Now a recognized author, he both fled the Siege and opposed the Commune. But Zola had spent thirteen years in the Latin Quarter, much of it minutes away from Père Lunette – and he critiqued these stereotypes ferociously. The government shuttered a paper just for printing him, but Zola got revenge with his novel L'Assommoir (1876).

Set in another poor area, the Goutte d'Or, L'Assommoir tells of lives destroyed by drink.3 The scandal it provoked was monumental, but the book is famous because it changed literature. This was not because of Zola's point that drink was killing, not "consoling" the poor. It was because his marginal characters spoke in their own voices. Zola took care to verify this "dialect" and one of his references was Alfred Delvau's Dictionnaire de la Langue Verte. Delvau may have provided the book's title, via his entry "ASSOMMOIR: A synonym for the most abject of bars".

The verb assommer means "to stun or knock senseless". Zola made it a household word and, in the process, turned every cabaret and bouge into an "assommoir". More importantly, he ushered in naturalism – a new type of writing based on first-hand knowledge.

L'Assommoir's crude slang and casual sex stupefied readers. Critics lambasted it as "foul" and "filthy" while cartoonists pictured Zola in chamber pots. But its characters turned up everywhere, on plates and posters, menus and souvenirs. Among the art at Père Lunette, wrote George Grigson, the fascinating reprobates "occupied a central place."

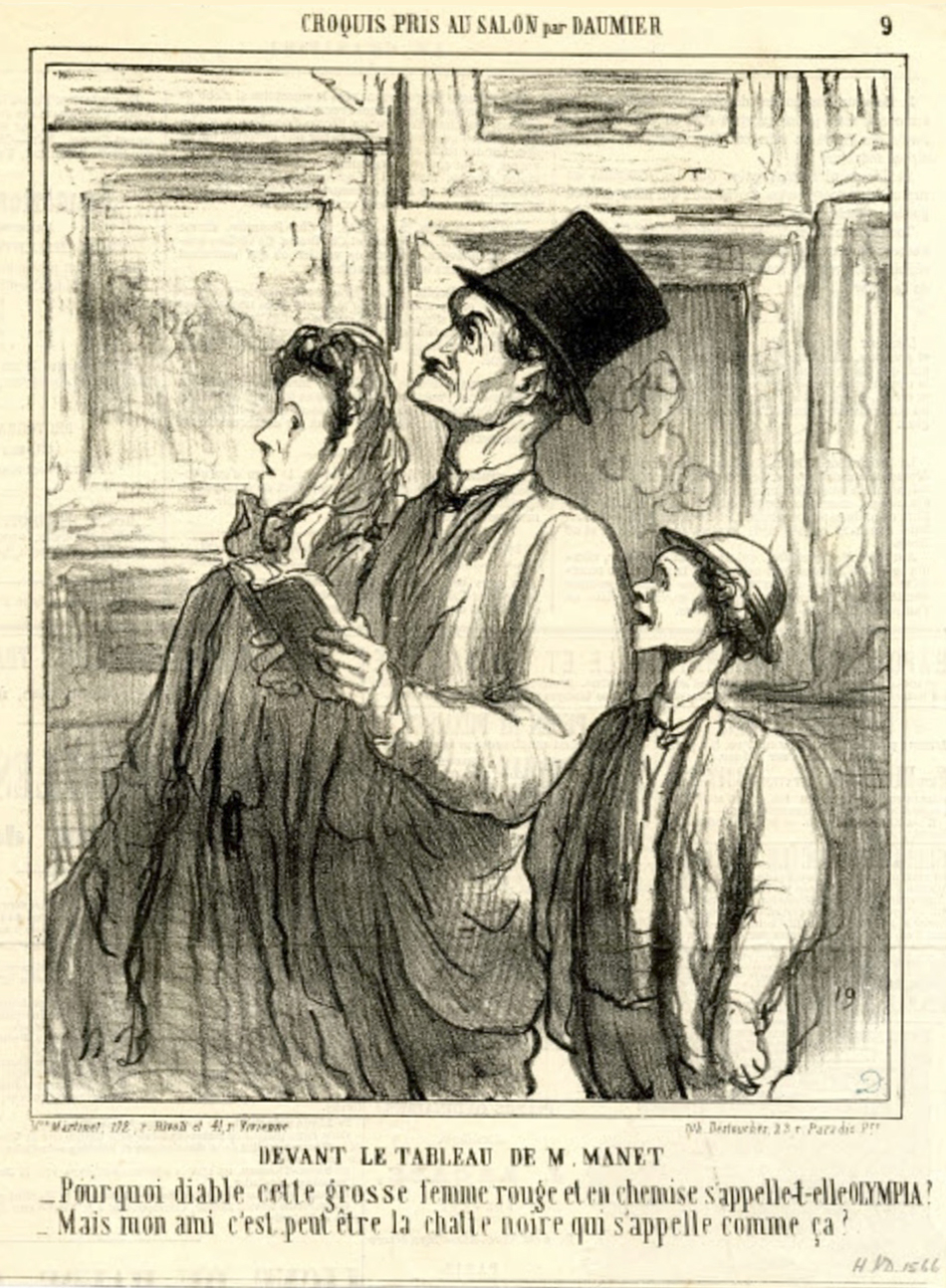

Zola was unfazed, because he relished a scandal. He had already championed artist Édouard Manet when his paintings "Luncheon on the Grass" (Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, 1863) and Olympia (1863-1865) led to a similar uproar. "Luncheon" shows two dressed men and two grisettes, one entirely naked, having a meal outdoors. Olympia depicts a prostitute and her black maid, the nude lorette reclining as she receives a client's bouquet. The furor the paintings caused stemmed from sex and social class, but it also derived from caricature. It made Olympia the century's most infamous work.

Prostitutes had figured in comic art for decades and public women were also known as "caricatures". But this just made the debacle worse. Both Manet's paintings were rooted in esteemed Old Masters. But, says curator Isolde Pludermacher, "Many critics saw them as huge cartoons… and just assumed Manet was mocking serious art." The late Françoise Cachin, an expert on the painter, agreed. "Because Olympia evolved into 'a masterpiece', people can forget Manet's full experience, especially the humor and literature surrounding him… It's perfectly possible he did intend some form of parody." 4

Cartooning had profound effects on Édouard Manet. His love for full-length figures in abstract space came partly from Spanish greats he admired. But it also owes a debt to "The French Seen by Themselves" (Les Français peints par eux-mêmes, 1842), with its plates by Monnier, Daumier and Gavarni. Manet made caricatures all through his teens and was still doing so when, at 28, he finally published one. He was a fan of Gavarni and very fond of the artist's lorettes. But Manet also loved his cartoons of artists' models as well as those of poor Parisians from "The Devil in Paris" (Le Diable à Paris, 1845). There were 208 of the latter, each conceived and captioned by Gavarni.

Many artists showed the poor's marginal jobs (les petits métiers) as picturesque. But Gavarni emphasized their insecurities. Any setback, as he shows, was potentially devastating. Manet's Olympia exudes the same fatalism. The modest dress of its sturdy, dark maid underscores Olympia's puny, pasty nakedness. The lorette's nudity looks less erotic than vulnerable – and yet two women's livelihoods depend on her body.

Paul Gavarni was a celebrity; his fans ranged from Delacroix to Dickens and Queen Victoria. Everyone knew his popular lorettes and they contributed to the rage about Olympia. In part, Manet's black-white, mistress-servant composition was intended to evoke America's Civil War. (The artist detested slavery and the French court's Southern sympathies.) But the real fury came from came from somewhere else. In households based around sexual commerce, as Gavarni taught, maids like Olympia's were always co-conspirators. The courtesan's personal maid was her confidante – the one who received and bargained with clients.

Olympia got Manet booed and pointed at in the streets, while both critics and cartoonists attacked him. When he claimed the painting mattered, Zola stood alone. Yet he boldly wrote that "When most artists offer us a Venus… they lie. Manet asks himself, Why lie? Why not be truthful?... He introduces us to a modern girl, one you might easily meet in the street."

Père Lunette's crowd did meet her in the street. Manet's model for both "Luncheon" and Olympia was the teenage Victorine-Louise Meurent. Meurent lived yards from the bar in rue Maître-Albert – the exact street where Manet's engraver worked. All its inhabitants patronized the local dives.

Did Manet actually meet Victorine Meurent in La Maube? Yes, claims his socialist pal Adolphe Tabarant and, certainly, he was no stranger to the slum.5 When Manet drank in the Latin Quarter, he liked the Andler-Keller and Le Père Armand (a bouge known locally as the "Loyal Pig"). To see a drinker at nearby Père Lunette, look no further than the artist's "Rag Picker", "Beggar with Oysters" or "Beggar in a Beret". 6

Many artists sought such drama in La Maube. Another one was novelist (and militant) Jules Beaujoint (1830-1892), who wrote books like "The Blood-Soaked Rooming-House". Beaujoint's first success was "The Nights of Paul Niquet" (1867). Its title referred to "Paul Niquet's", a legendary bouge. But, because Niquet's had closed, Beaujoint made all his observations in Père Lunette. The bar's enraged proprietor sued him for defamation – but Beaujoint won and sealed the bar's reputation.

In 1879, Zola's best-selling L'Assommoir became a play. The first night was more than merely a premiere; it was, wrote a critic, "the year's major event." One man attending was theatre pro Ludovic Halévy, suave co-librettist of the opera Carmen.

The play so intrigued Halévy that he ventured into La Maube. He sought the protection of Gustave Macé, Chief of Investigations for the Paris police. But, inside Père Lunette, Macé was soon recognized. A small brunette taunted him that she had just left Saint-Lazare – the city prison for diseased prostitutes. ("For two months I've drunk nothing but water. As you can see, I'm making up for that!"). Halévy was mesmerized by the reality Zola had captured: "There they all were… sombre, bleak, drunk, defiled… a sickly girl, maybe ten… asleep beside her emptied glass … toothless old women, their skin as tanned as parchment… hideous girls whose very bones slosh with booze."

At one point in the Château Rouge, a girl and her pimp sat down beside him. "Although she was young and blonde and had nice eyes, she was ravaged by disease. She downed every new glass like a kind of machine, in a single motion, while staring into space." Her man drank, rolled his cigarettes and smoked, "seeing nothing and hearing even less." Neither said a word to him or one another. They seemed the incarnation of a painting Halévy knew – his close friend Edgar Dégas' much-derided "Absinthe".

Halévy liked the bar's Père, Paul Aldéricque Mary. Mary was 47, with a wife and two young sons. He boasted that a string of artists favored Père Lunette; something, it seems, that was essentially true. (A portrait of Mary by the painter Claude Goubot even appeared at the 1882 Salon.)7 One such customer may have been André Gill. For, despite playing a part in the Commune, Gill had managed to survive its bloody end.

He still lived and drank in the Latin Quarter, but Gill now eschewed his radical past. "These are boring times," he wrote a friend, "but I am part of them... Trees have grown over the bodies and birds are singing in them… and it's time for all of us to hear their songs."8

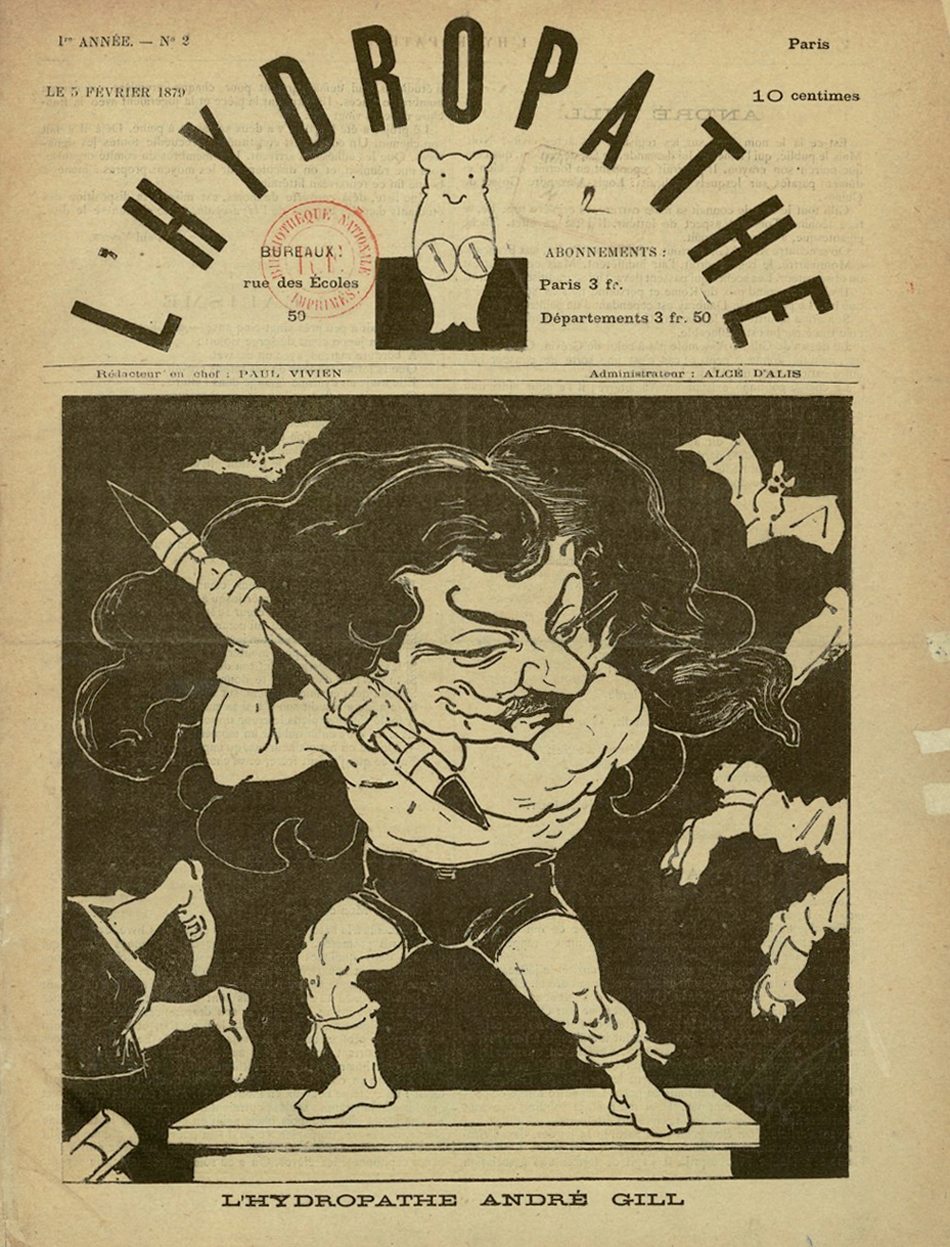

Most of the Paris that surrounded him agreed. During the Second Empire, it used the word "cabaret" – the term for a modest bar – as an insult. A cabaret was just a dive like Père Lunette. By 1878, however, this had changed and a "cabaret" became a night of merry performance. Such events started in the Latin Quarter, via a club called the Hydropathes Café.

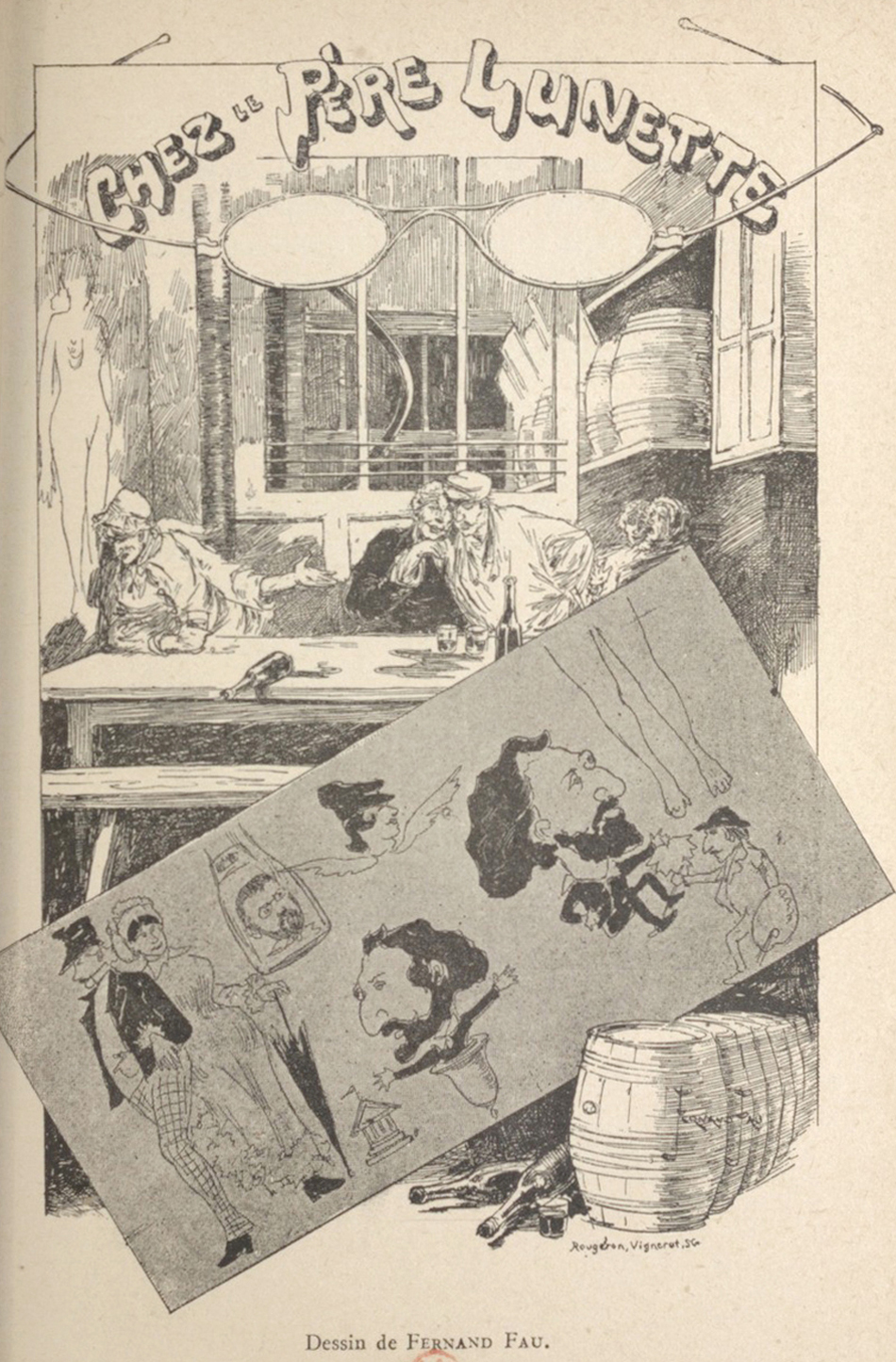

The Hydropathes were a loose and shifting gang. Their evenings attracted characters from policeman poet Ernest Raynaud (1864-1936) to André Gill's young assistant Émile Cohl (Émile Courtet, 1857-1938). Cohl – eventually the inventor of animated cartoons – edited the group's comic paper L'Hydropathe (1878-1880). Three key Hydropathes were cartoonists: Gill, now 40, 28 year-old Georges "Cabriol" Lorin and Lucien Labbé, who was 23. Labbé was a regular at Père Lunette and a star on its walls. In 1881, with Édouard Manet and caricaturist Ferdinand Fau, he launched the art gazette Le Rapin ("The Poor Painter"). Labbé's contribution was a piece on Père Lunette, "The Lower Depths of Paris", illustrated by Fau.

The Hydropathes helped engineer a shift in satire, a move from politics to comedy of manners. But this was less a choice than a response. For, in those governments which succeeded the Commune, royalists and republicans battled for power. Faced with right-wing papers like Le Triboulet ("The Jester", 1878-1921), politicians on the left behaved just like the right – banning, jailing and fining artists. They killed a rightist paper called La Trique ("The Cudgel", 1880-1881), pulping its issues and getting police to threaten vendors. "The Cudgel" was reduced to promising readers that, if they sent in stamps, they could be mailed cartoons.

On July 29, 1881, censorship of caricature was finally abolished. That same year, most cabarets quit the Latin Quarter. The thriving scene moved to Montmartre where, in clubs like the Chat Noir, the Mirliton and the Moulin Rouge, it remade ideas of "bohemia". The paying crowds who flocked to these clubs were mostly bourgeois and came to see stars: the cancan dancer La Goulue or street singers like Aristide Bruant and Yvette Guilbert.

Such celebrities dramatized "bohemia". But their exaggerated images grew more and more popular – especially when artists like Gill, Toulouse-Lautrec, Willette and Steinlen made both the performers and their venues into icons. Other satirists followed this lucrative path and real politics were, essentially, abandoned. Their place in comic art was taken by fantasy, sex and personality.

Now even Père Lunette's "museum" gained celebrities. But, hidden away in its back room, such cartoons retained the bar's militant bent. One showed André Gill's pal Clovis Hugues, a Hydropathe who went to prison during the Commune. Another featured atheist Emile Littré (the man behind a new dictionary) as a bespectacled monkey. The image came from a cover by André Gill, in which Littré and Charles Darwin were circus chimps. Was the bar's copy done by Cohl or even Gill himself? Sadly, it's impossible to know.

Père Lunette now courted the status of "cabaret" and Père Mary held performance nights of his own. Louis Barron, back from prison, left a picture of one. In front of the Senate's art-covered wall, he writes, a "former actress" called Fat Sara warbled tunes. She was followed by a stout, singing builder and then by a man with only half his nose. (His ballad featured Christ as a socialist – and it won him rapturous applause.) The menu, Barron says, was "all political satire… satire being Père Lunette's one link to society."

Père Lunette's evenings produced their own celebrities. One was artist and poet Ferdinand Fantin (1856-1888), who had run a comic journal in Nice. Another, Jacques Autissier, was an absinthe addict. Both men specialized in reciting La Description, Fantin's lengthy celebration of the art.9 La Description mentions many caricatures – from Communard Henri Rochefort (famous for a prison escape) to the sculptor (and republican) Auguste Rodin.

Two of the cartoons it venerates can still be seen. One is Zola's head in a bottle labeled "Naturalism". The other shows a local pimp, his pregnant girlfriend and their dog. It was once captioned "This sly hustler is about to be made a husband."

Louis Barron was right – Place Maubert would never be Montmartre. Yet artists like Lucien Labbé kept on coming there. They replaced the Hydropathes with "The Hirsutes" and accrued fans like the writer Paul Duval (1855-1906). Known as "Jean Lorrain", Duval was tall and flamboyantly gay. He was an ether addict (and a hemophiliac) who was distinguished by powdered cheeks, kohl-rimmed eyes and, on one occasion, bright pink tights. Although he cut a curious figure inside Père Lunette, as Paris' best-paid journalist he made it famous.

Lorrain's friend Marguerite Eymery (1860-1953) lived a stroll from La Maube. Known as "Rachilde", she too was scandalous – thanks to her pornographic novel Monsieur Venus (1884). So transgressive it had to be printed in Brussels, this transsexuality and necrophilia. Deceptively petite and pretty, Rachilde dressed as a man. Her calling card read "Rachilde, Man of Letters".

Rachilde and Jean Lorrain were equals for audacity. He liked the rent boys who used La Maube's cheap hotels and once sent Rachilde a midnight SOS from one. She got out of bed, dressed and – armed with a letter-opener – came to his rescue. ("The hoodlum who fetched me led me to a door and, when I got it open, I saw Jean's head on a sheet… At first I thought he had been decapitated. Then I realized a sheet was wound around his throat and his arms had been tied to the bed… 'Don't ask questions!' he barked. 'Until they stole my clothes, I quite enjoyed myself!'")

This pair explored La Maube with Paris' oddest cop, the hyperactive Oscar Méténier (1859-1913). Méténier's moustache was as big as his crush on Rachilde, who he squired around dancehalls and dives. (His mash notes to her began "My darling boy"). By day, Méténier dealt with murders and arrests. But, outside work, he was a dramatist – one whose kitchen-sink plays changed theatre.

At the age of 38, Méténier bought a playhouse. He dubbed it "Le Grand Guignol" and, working by subscription to evade the censor, staged what he called "naturalist" drama. These were plays replete with shocking firsts like domestic violence, incest and prostitution. They forged their own school which, as it grew more extreme, turned ''Grand Guignol" into a synonym for horror.

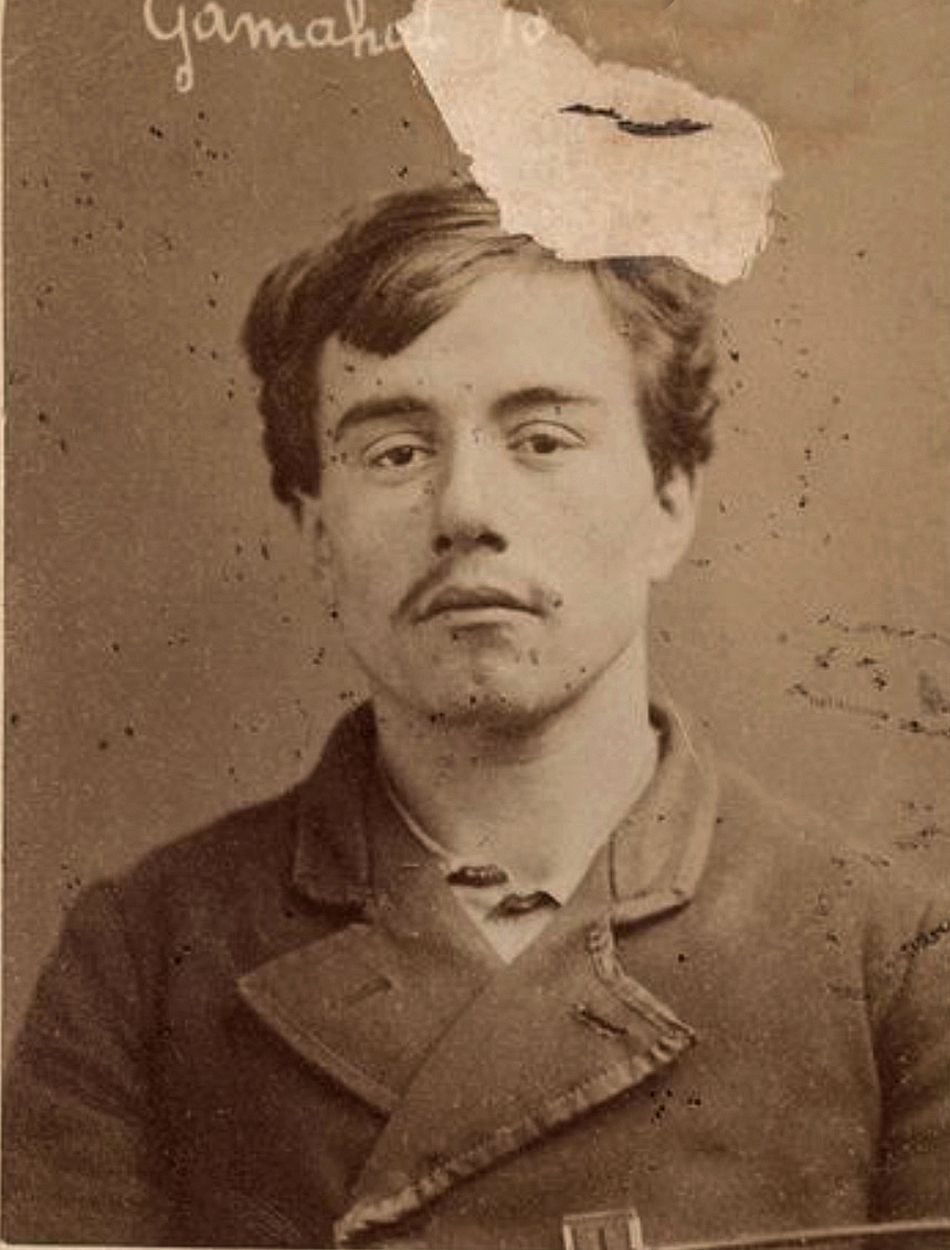

Méténier's 1887 En Famille ("In the Family") took place in a criminal home next door to Père Lunette. His 1889 "The Snitch" (La Casserole) went even further, setting its action in a replica of the bar. This play's extras were real drinkers from Père Lunette and one character, "The Terror of La Maube", was inspired by the local bouncer Gamahut.

Adolphe-Tiburce Gamahut was 23 and six feet tall. At 14, he had been a trainee monk – until a passing circus taught him to wrestle. This led to Paris and the bars around La Maube, where Lorrain, Rachilde and Méténier met him. They called him "Champion" and felt, in Méténier's words, that he was "gentle despite his Herculean strength". But, while Gamahut was friendly with the slumming chums, he was closer to pimps Paul Midi (known as "The Lawyer"), Bayon ("The Little Soldier") and Carrey ("Spit Curl"). On November 27, 1884, with the builder Soulier, the gang set off to rob a widow named Ballerich.

When Madame Ballerich came to her door, Gamahut forced it. He then knocked her to the floor and stabbed her in the neck. The day before, her neighbour Léon Jollet – who was 11 – had seen Bayon and Soulier slinking around. This time, he passed Ballerich's door and saw them with her corpse. Jollet ran for police, who tracked the gang back to La Maube. Within a fortnight they were all in custody.

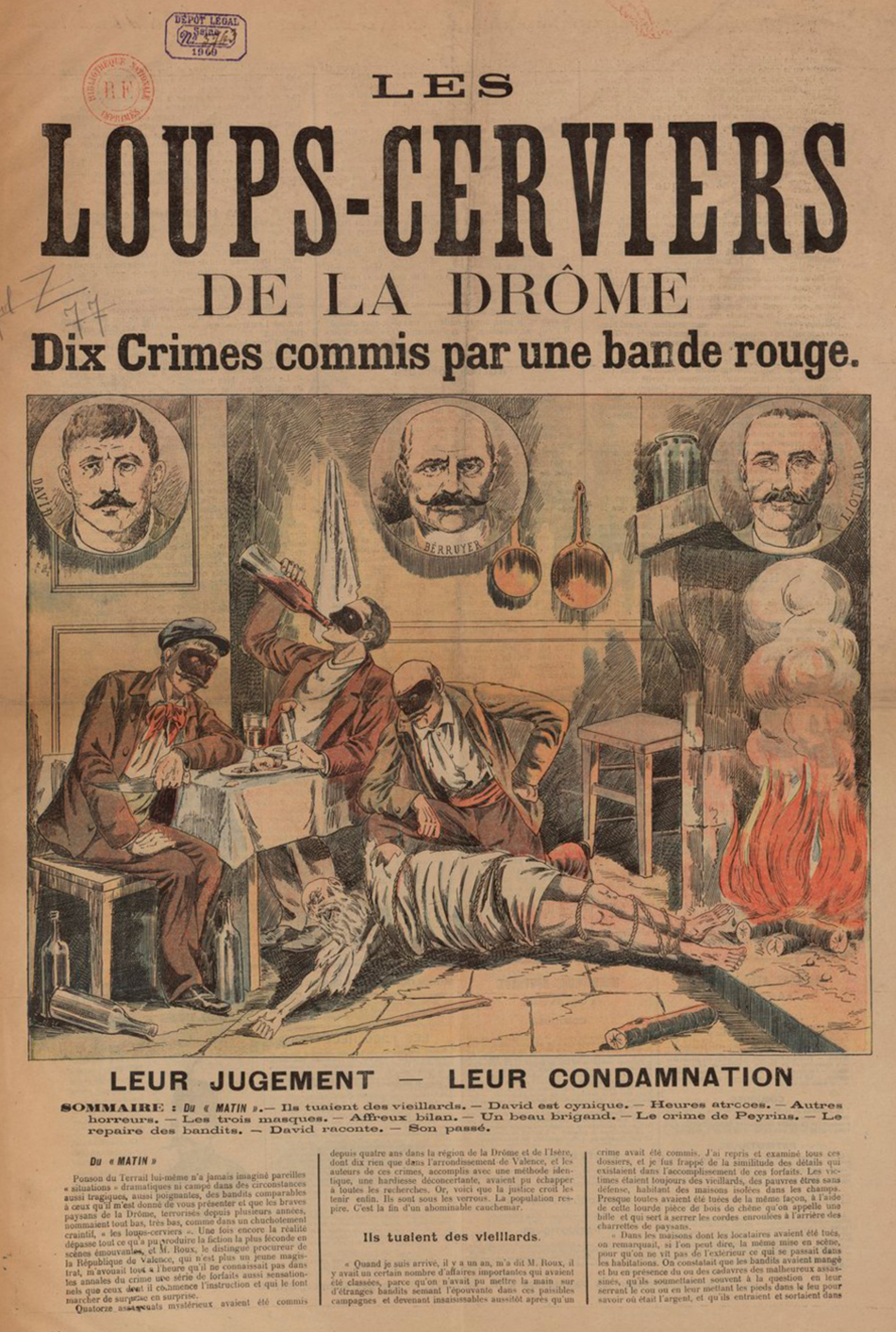

The quirky murder was pivotal for Père Lunette. In the wake of the Commune, public fears about lawlessness ran deep. One expression of this was a new obsession with crime – which grew just as immoderate as the era's taste for drink. By 1900, writes Dominique Kalifa, "crime appeared to be the main activity of the French". From plays and novels to news, it dominated everything.

Crime already had its own PR machine: the network of "canards" or broadsides sold in the streets. Canards featured lurid illustrations with screaming headlines, such as "RAPED BY A SHEPERD then EATEN by his DOGS!!!". Many were produced in Paris but sold to rural markets, which enabled printers to invent some of the "crimes". These were always set in famously bad locations – like the bars and garnis of La Maube. One, "The Crime of Place Maubert", was re-used for decades.

La Maube was also home to a major canardier, the Maison Aubert (later Maison Aubert-Baudot, then Maison Billy). This was a family business less than a minute from Père Lunette which, by the 1880s, hired well-known artists. There, caricaturists like Henri Demare (1846-1888) and L'Assiette au Beurre's Bernard Naudin (1846-1946) illustrate such crimes as "60 YEAR-OLD CUT to PIECES!!! BOILED and then FED TO HIS PIGS!!!".

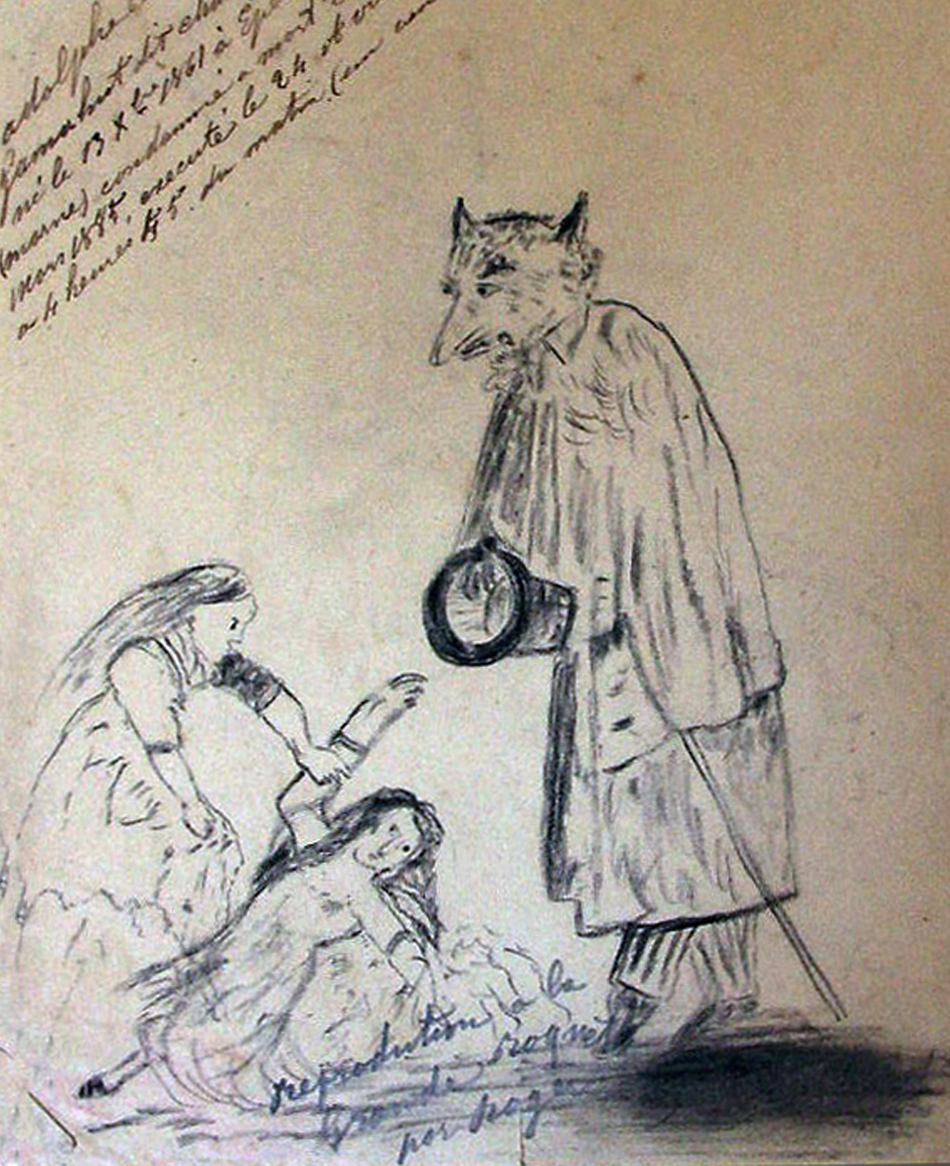

This crime mania meant Gamahut's murder was huge. In the press and on the stand, the killer blamed his sad situation on La Maube. But his defense had a special angle for, as it happened, he too was an artist. In a bid to demonstrate his "sensitivity", cartoons poured out of Gamahut's cell.

Gamahut was guillotined on April 24, 1885. The media fixation on his crime and execution (plus the medical experiments on his severed head) kept attention riveted on La Maube. Writers and artists who knew it cashed in – and every portrait they created featured Père Lunette. Tales of the bar's "sinister frescoes" reached as far as the New York Times.10 At cartoonist Alfred Grevin's wax museum, an effigy of Gamahut's head drew tourists of its own. La Maube's reputation sank even further.

It was this infamy that linked Père Lunette to Tom and Jerry. Tom and Jerry were born in 1821, when English journalist Pierce Egan published Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, Esq. and his Elegant Friend Corinthian Tom, Accompanied by Bob Logic, the Oxonian, in their Rambles and Sprees Throughout the Metropolis. Egan was a well-known boxing journalist, able to commission his tale's cartoons from the Cruikshank brothers. Everything in the best-seller came from a single trope: posh boys setting out to see a city's "lower depths". This idea ran and ran, generating a century's worth of copies and parodies.

Perhaps its oddest legacy was Paris' "Tournée des Grands Ducs", the "Grand Dukes' Tour". It took off around 1885, in the wake of printed guides to Tom and Jerry's Paris. The armchair handbooks had titles such as Paris Horrible, Paris Original (George Grison, 1881); Paris Etrange ("Unknown Paris", Louis Barron, 1883), Paris-Escarpe ("Hoodlum's Paris", Charles Virmaître, 1887) and Un Joli monde ("What A World!", Gustave Macé, 1887). All took their readers into Père Lunette.

Some were penned by journalists and others by policeman. But their popularity led to the "Tour". Jean Lorrain credits the idea to a policeman, 38 year-old commissioner Marie-François Goron.11 Goron's special brainwave was Tom-and-Jerry tours – slumming expeditions that rapidly became surreal. A Tour's upscale voyeurs were treated to a bal, a dancehall filled with prostitutes and pimps. But they were also shown the city's grimmest garnis, served drinks in sleazy bouges and hosted in soup kitchens. As the outlandish outings grew in popularity, rival routes were offered. But Père Lunette remained a treasured highlight.

The Tournée's nickname came from two of Goron's clients, Russia's Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich (1847-1909) and his brother Alexis (1850-1908). In November of 1891, they visited Père Lunette. But nobles grand and lesser eagerly embraced the Tour, including Sweden's Oscar II (1829-1907), Portugal's Charles I (1863-1908) and Italy's Victor Emanuelle II (1869-1947). All were escorted through La Maube by top policemen.

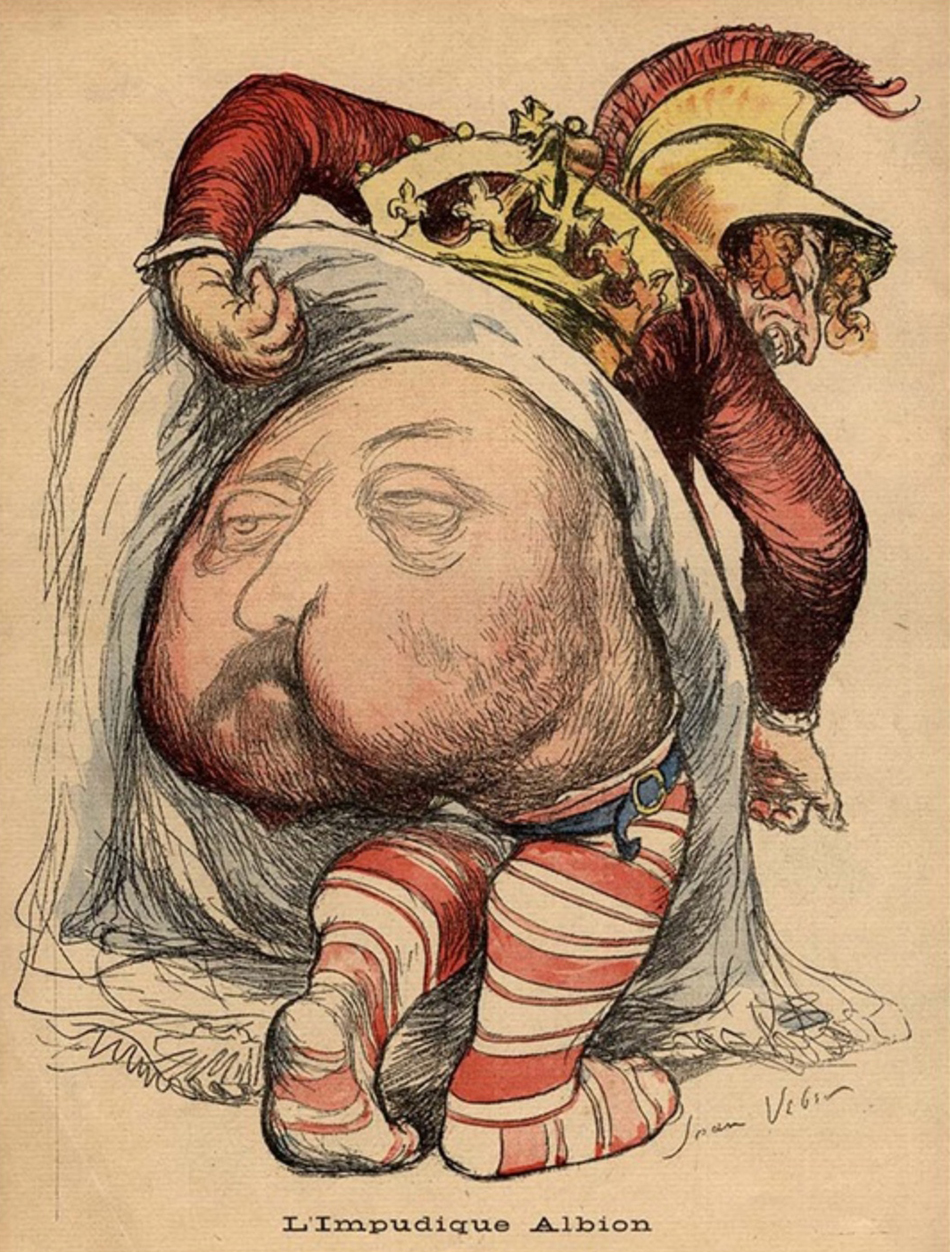

The Tour's most famous fan was Queen Victoria's heir, Prince Albert Edward. Known as "Dirty Bertie", he was a devotee of Paris bars and brothels. All Bertie's trips to Père Lunette were made in disguise. Yet cartoonists Jean Veber (1864-1928) and Georges Bigot (1860-1927) dogged his steps to keep his scrapes in the press. In 1902, when Bertie fell gravely ill, a Paris satirist published his "Last Will & Testament". Among its spoof bequests, one read: "To my pals at Père Lunette, I leave my Lancers cap and my Horse Guard undies. May they grace the bar in memory of our happy times!"

Jean Lorrain became a great promoter of the Tour. He took both locals and visitors on it (including Montmartre's Yvette Guilbert – on Christmas Eve! – and Spanish countess Emilia Pardo Bazin). The year before he died, Lorrain also wrote it up for a science magazine, Je Sais Tout ("I Know It All"), with illustrations engraved from actual snapshots. Lorrain's pic of Père Lunette, which is wholly retouched, even captures a cartoonist: David Widhopff from L'Assiette au beurre.12

Père Paul Mary never saw such triumphs. On February 24, 1888, he died of pneumonia. But his demise at 56 made front pages. "Do you know Père Lunette?" asked Maxime Boucheron. "All true Parisians have been there once, if not twice." "Mère Lunette", Mary's widow, took over the bar. Three years later, the baton passed to her nephew Jean Chanson.

By now, some felt the place had ceased to be a bouge; its clientele, they maintained, were just performing. But Père Lunette's true character was elusive. For ever since it opened, the bar had attracted (and welcomed) voyeurs. One cop remembered regulars who ribbed each other "Hey, be polite… mustn't scare the chic folk!"

Few such "chic folk" showed up year after year. But Oscar Méténier did. In addition to running the Grand Guignol, he also ghostwrote songs for Aristide Bruant. Like Méténier's plays, Bruant's hits revolved around the woes of poor Parisians. But, while the former cop died at 54 of syphilis, Bruant aged and prospered. He owned his own cabaret, steered his own PR and made a fortune selling copies of his songs. Méténier brought many of these their grit – and it was thanks to him they name-checked spots like Père Lunette. Bruant's audience, he felt, mirrored that of the bar: "It embraced both the oppressed and those oppressing them."

One fan of both men was playwright Oscar Wilde. In 1898, after his time in prison, Wilde discreetly took lodgings in the Latin Quarter. But he also joined the crowds at Le Grand Guignol. After seeing Méténier's "Revenge of Dupont the Eel", Wilde enthused about it to a friend: "The Grand Guignol is the first theatre in Paris. There you see the primitive tragedies of real life… as ugly and fascinating as life itself."

Living such tragedy, however, proved less enthralling. Lionized in Paris early in the 1890s, Wilde now found himself persona non grata. One of the few who refused to shun him was the cartoonist Ernest La Jeunesse (1874-1914). La Jeunesse, also gay and equally eccentric, was a pillar of mainstream newspaper life. Yet he remained a staunch friend to Wilde. He even trekked across the Seine to the Latin Quarter so they could – unobtrusively – dine together.

Wilde had another advocate in the area, an American expatriate called Stuart Merrill (1863-1915). Merrill was a poet who, in happier days, had tagged along with Wilde on cabaret crawls. The playwright's fancy clothes, he once wrote, convinced people he himself was a "Grand Duke". Now, however, Merrill sent his friend to cheaper, less public bars.

Was one of Wilde's choices Père Lunette? It's perfectly possible – for, in 1891, he and Merrill drank there together. Wilde may well have returned, just as he sampled other local bouges like L'Oeil de Verre ("The Glass Eye"), Le 26 (Place Maubert's anarchist lair) and Le Drapeau ("The Flag"). Like Père Lunette, all offered cheap drink, rent boys – and anonymity.

After Wilde visited Père Lunette in 1891, he bragged about it to his translator Marcel Schwob ("I spent last night among the most terrible creatures… all of them hoodlums, killers and thieves").13 Schwob knew the bar well but he saw it as filled with "barroom orators, casual types and also-rans." But, on Wilde's return, Schwob too avoided him. The ostracized writer grew poorer, drank more and, finally, took ill. On November 30, 1900, in a cheap hotel, Wilde breathed his last. He died a fifteen minute walk from Père Lunette.

The bar survived Wilde by under a decade. In 1908, Père Jean Chanson's rent was doubled and, despite many efforts, he failed to meet it. Just before his eviction, Chanson whitewashed all the walls.

Within weeks the bar re-opened as an eatery. Its new proprietor, a Monsieur Delrieu, had razed the interior wall and applied yellow paint. Yet the infamous cartoons soon re-appeared, a few now signed "Julien Grenault". Some of what "Grenault" reinstated, however, had differences. That naked prostitute washing herself, for instance, re-appeared almost fully clothed. The pimp on whose back her foot had stood was missing – prudently replaced with a footstool.

Maison Delrieu might have evolved art of its own. But Père Lunette sits two hundred yards away from the Seine and, ten months after the café's opening, it overflowed. The Great Flood of 1910 submerged the rue des Anglais, swamping its ground floors and basements for a month. When number four was finally recovered, most of its damages were literally papered over.

Those layers of wallpaper helped preserve its art. The cartoons spent almost nine decades beneath them – until 1999, when a private owner found them. In 2007, the City of Paris purchased the site, financed its restoration and officially declared it a Historic Monument. Now, the premises are owned and run by SEMAEST, the Societé d'economie mixte de la Ville de Paris. Their tenant is a publisher, Charles-Henry Dubail, whose imprint Edisens deals in history and French. Dubail needs no persuading that the walls are important.

In Père Lunette's time, just one man shared that view. He was John Grand-Carteret (1850-1927), one of caricature's first champions. In 1886, in his Raphael et Gambrinius, Grand- Carteret devoted six pages to Père Lunette. Despite a caveat – "This may push my whole idea of art too far" – he hailed the bar's bohemians and their comic daubs. The cartoons, he wrote, embodied their camaraderie and their convictions, "and they didn't give a damn if that pleased anyone else."

We owe our glimpses of their world to the bar's voyeurs. But they were present only as investors. "What a spectacle!" exclaimed Ludovic Halévy. "We stayed half an hour, but I could have stayed all night!" Others, like Oscar Wilde and Oscar Méténier, also thrilled from mingling with such untouchables. Yet all of them sought to merchandise their experience – they preferred society's approval to that of La Maube.

Not so the comic artists of Père Lunette. Like the causes they depicted, they were crushed by life. Yet the specters of their stubborn wit endure.

* * *

- La Maube was also known as la Maub' as well as, from around 1900, "La Macobo".

-

Many names for the era's dives came from what they served. For instance the popular "prune" (brandy sweetened with a plum) led to some bars being called "prunots". Similarly, "a Chinois" was a bar serving brandy flavored with a Chinese orange.

- Zola's research into and use of the Goutte d'Or in L'Assommoir is its own story, commemorated today by the name of the 18th arrondisement's "Place de l'Assommoir".

- Caricatures focused on Olympia's soiled feet, for instance, relate directly to other cartoons (and art students' jokes) about artists' models. Also, when critics compared Olympia to a corpse in the morgue, they weren't being metaphorical. The Paris morgue was a free "exhibit" of corpses and it was popular with every class. In 1864, it had just moved into a fancy, brand-new, building.

- Édouard Manet lived, worked and socialized largely on Paris' Right Bank. But he found models for his work everywhere. (Two of his paintings feature a ragman he met in the Louvre.)

- In "The Street Singer" (La Chanteuse de rue), Manet shows Meurent in a dirty dress, departing a bastringue. She is pale and nibbles on cherries from a paper bag. This echoes the cherries in Manet's Le Déjeneur and his "Boy with Cherries". (For "Boy", Manet's model was his assistant Alexandre, a street boy who later hung himself in the studio.) Cherries were one of the poor's few luxuries and, immersed in eau-de-vie, they made the drink called a "cerise" (cherry). In polite society, this was a "guignolet", after the dark cherries called "guignes". But to "porter le guigne" – to "have bad luck" – became, in slums like La Maube, "avoir la cerise". There, a cerise (a "cherry") was someone jinxed by their circumstances. Cherries signified losing out in life..

- Claude Goubot was well-known. In 1884, with pals Odile Redon, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, he founded an artists' group called the Societé des Artistes independants (he served as its Secretary). This association is still around today.

- André Gill never escaped his Communard past. After several breakdowns, he was committed to the Charenton asylum where, in 1885, he died. Much of his torment dated from the Commune – especially when, for 36 hours, he hid in a theater basement, watching soldiers play with dead bodies through a window.

- Versions of "The Description" appeared in several papers, as well as in memoirs. Fantin's drinking pal, the sportswriter Rodolphe Darzens, also included it in his "Paris Nights" (Nuits à Paris, 1915)

- In an 1888 piece about Père Lunette, the New York Times claims Gamahut was arrested there. Several papers echoed this. But Gamahut worked for Père Trolliet at the Château Rouge (not Père Lunette) and he was arrested outside the capital.

- There is a summary of the Tournée des Grands Ducs' full history in Dominique Kalifa's trailblazing Les bas-fonds (Seuil, 2013). As Vice, Crime and Poverty (Columbia University Press, 2019), it is available in English.

- By 1900, the Tournée des Grands Ducs featured in stories, avant-garde novels and on the stage. By 1909 it was a film, Léonce Perret's silent La Tournée des Grands Ducs. The expression "faire la Tournée des Grands Ducs" is used today but it now means only "having a big night out".

- Little is known about this visit, on which Wilde and Merrill were accompanied by Wilde's visiting friends Robert Sherard and William Rothenstein. Both of the latter mention it very briefly in memoirs but focus on the group's time in La Maube's Château Rouge (the place most associated with Gamahut, who worked and trained there). Both imply that Wilde was horrified by La Maube; something belied by the relish with which Wilde spoke to Schwob.