I’ve received more Google Alerts in the last two weeks than in the entirety of the system’s existence. My alerts include “Alfred E. Neuman,” “Spy vs. Spy” and — can you guess? — yes, “MAD Magazine.” When news leaked on July 3rd that MAD would no longer be publishing new material on a regular basis, social networks and media outlets exponentially reacted in a flurry of shock and confusion. There was an impressive outpouring of emotion on the magazine’s behalf, singing its praises and bemoaning a future where there might no longer be a place for MAD, the original disruptor of homogeneous American culture.

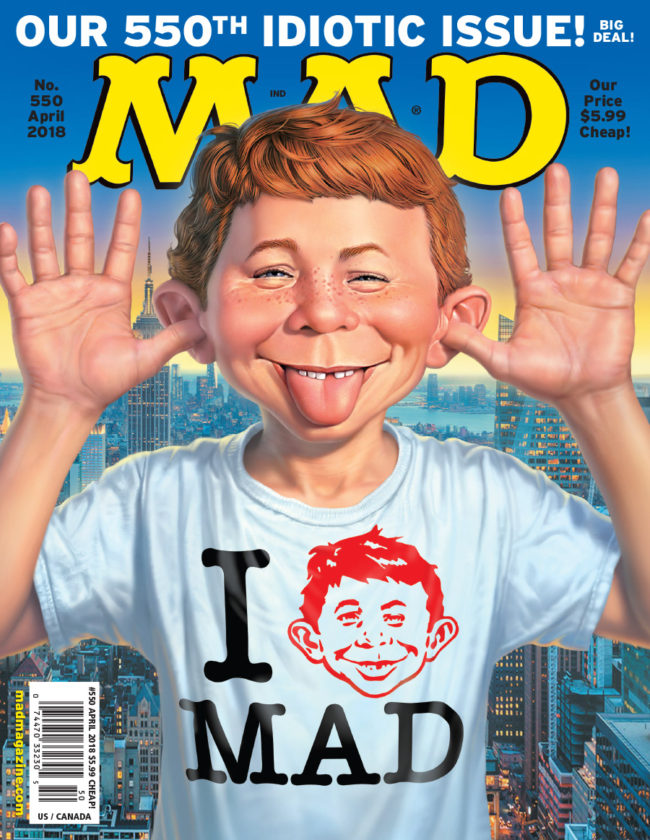

550 issues of the magazine were produced in New York City. I worked on the final 150 of them. Officially, I was a member of the MAD Art Department, though my roles spilled into editorial, talent scouting and the amorphous responsibility of “coming up with new ideas.” When MAD’s editorial offices relocated to Burbank, I chose to stay behind. I’ve freelanced for and maintained friendships with some of the California staff, so I received the recent news just before the general public. It’s been fascinating, touching and irksome to watch the surging response. A running theme, that MAD’s not as vital as it used to be, isn’t exactly wrong, but I feel it’s an oversimplification. Relevancy is relative, especially in a fractured global culture. The more MAD memorials I read, the more I realize there’s a mourning not just for what MAD represented at its peak, but for the singular, unique thing it is and always has been, even as its sales numbers declined.

To open an issue of MAD Magazine, from any point in its history, is to encounter an assemblage of many of the most brilliant writers, artists and satirists working in that era. It is a whole package you can hold in your hands, an ensemble of voices echoing out as one, an orchestra of insanity, hilarity, and cultural acuity. Though it’s had its imitators, and influenced many successful comedic endeavors, there is truly nothing else like MAD — a regularly-produced menagerie of carefully crafted, intertwining words and visuals. Within the staff, we were never satisfied if an issue was just okay — we always wanted the damn thing to be good. And good takes time. Even still, in my 17 years, we never missed one print deadline. A MAD reader could bank on the fact that a new issue was on its way, and would get there when it was supposed to.

When I told people I worked at MAD Magazine, they often looked at me sideways — was I kidding? Did they hear me right? And when I said I worked in the Art Department, they’d ask if I was one of the cartoonists. Well, no. But if not that, then what DID I do? Just about everything else.

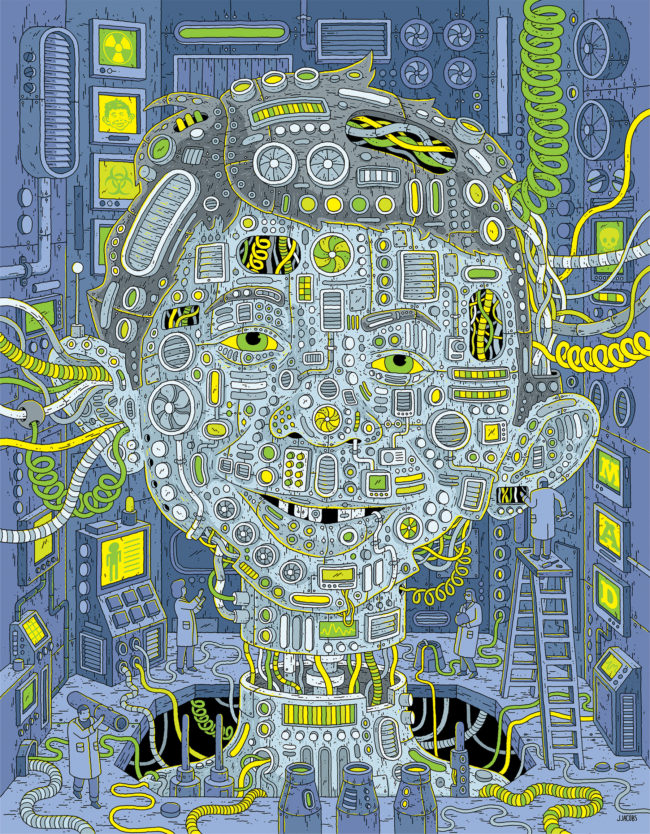

We used to joke that most people think MAD articles were born when a writer called an artist with a title and some gags. The artist would draw the whole thing up, send it to us, and we’d put it in magazine. Repeat a few more times, et voila — a complete issue. For all I know, that’s how most anthologies work. But despite appearances, MAD was never an anthology. It always had a massive amount of editorial oversight. We’d sometimes ask writers to tackle specific subject matter, and we’d frequently receive and review pitches — but we’d always assign the art ourselves, after the intensive editorial process was complete and the article’s layout was designed. Every word, every drawing, every silly little piece of chicken fat was deemed MAD-worthy by someone on the staff, and ultimately vetted by the editor at the top. There were only four big shot editors in MAD’s 65 years in New York: Harvey Kurtzman, Al Feldstein, Nick Meglin and John Ficarra. The MAD voice was nurtured, protected and updated by them, under the direct and then symbolic guidance of iconoclastic publisher William M. Gaines. The entirety of each issue of MAD reflected that unique sensibility.

We created much of each issue in-house: writing jokes, answering letters, conceiving covers, building props, posing for ad parodies. If you didn’t see a credit, 99.9% of the time it was made by the staff. Who did you think came up with the pun-filled department heads? Kaputnik?

Of course, our true purpose was to disappear into the ink and let the freelancers’ stars shine. MAD would be nothing without “The Usual Gang of Idiots,” as our writers and artists were famously known. The phrase has often been parsed, understandably —“usual” having a very specific meaning, “gang” implying a dedicated and core group of members. I’ve heard it said that that to be included in the UGOI, a contributor should appear in every issue. With rare exceptions, that almost never happened. It’s true that for much of its history MAD was considered a “closed shop,” its pages filled with the work of names that would become inextricable from MAD. However, if you look closely at the UGOI’s history, you’ll notice members came and went, while new recruits snuck in — becoming long-running fan-favorites with years of MAD material under their belts, yet still perceived as the “new kids.”

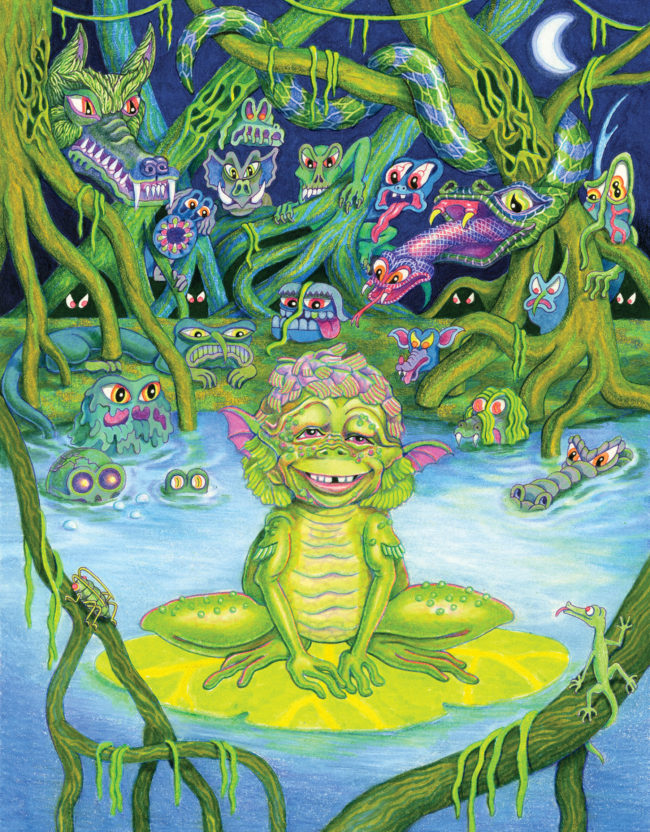

In the 1990s and 2000s, we opened up our talent roster even further, finding new contributors from the worlds of fine arts, editorial illustration, independent comics and the web. Though we remained dedicated to the promotion of the central Usual Gang — all of whom were always at the top of their game — we purposely created new sections of the magazine that would allow fresh faces to join in the fun. On the art side, that meant opportunities to contribute spot illustrations, comic strips and gallery pieces. Many of the MAD contributors of the last thirty years are among the most celebrated, successful, noteworthy creatives of modern times. Others appeared in MAD at the beginning of flourishing careers, both within our pages and beyond.

A difficult truth: not everyone was right for MAD. A funny writer can find it challenging to adapt to visually-driven humor, and artists who excel in their specific style aren’t always able to set a narrative scene or zero in on a joke. There are creative types who didn’t like being edited, didn’t want to put in the extra work when asked for a revise, or didn’t understand why we weren’t just outright buying their pitches. I know that some of them thought we were out of touch and unwilling to adapt. On the contrary, our goal was to continuously build on what the magazine could be. Of course, not everyone on staff always liked every single thing we published, but we understood what worked in MAD. When the material we featured surprised us or made us laugh, we knew there was a reader out there who would feel the same way. If a submission wasn’t the right kind of funny, or had a flat punchline, or was too similar to something we ran in 1972, it wasn’t getting in. And hey, it’s not you — it’s the joke! No matter how many times I’d repeat that, I’d still encounter people who thought they’d somehow earned the right to appear in our pages. MAD was never a place you deserve to get into simply because you’re a working professional, and certainly not because your friends say you’re funny. We weren’t there so you could add a checkmark to your bucket list.

To truly succeed at MAD was to put it above your own ego. The staffers and freelancers who flourished are those who understood that the reader community and MAD ethos were the priority — and who knew that few opportunities in life would make them feel as good as working on MAD Magazine, and all that came with it. Making each other laugh in editorial meetings, getting called a clod over stupid misunderstandings, oohing and aahing as we’d crowd around a piece of freshly delivered artwork. Lunch visits from freelancers — some of the greatest minds, and kindest people, the world has even known. The thrill of coming up with a funny cover idea, the shock when a cover you didn’t think was anything special goes viral and sells extra copies. The smile on your face when the Bart Simpsons of the world show up for an office tour, eyes bulged and mouth agape. Sharing the pride of a new staff member holding the first issue they worked on. Veteran artists you’ve long admired saying that appearing in MAD was a career highlight, and young cartoonists telling you being published in MAD validated their career choice to their parents.

Much of the recent reporting implies MAD has been swallowed by the internet, which feels disingenuous. We had accounts on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram; we posted a few videos on YouTube and even had a Snapchat channel. Turns out it’s not always so easy to make money on those platforms. John Ficarra had a pull quote from The New York Times taped to his office door: “Free is not a business model.” We had contributors to pay, so we focused on the magazine. Yes, the magazine — a simple pile of paper held together with staples, covered in ink and sold at stores. A worn, disintegrating copy, with two distinct creases across the back cover, that you’ll never say goodbye to. A mylar-bagged, pristine edition with Alfred E. Neuman as Darth Vader on the front. The first issue you bought at the deli, the first issue that arrived in your mailbox, the copy your parent gave you, the copy you gave your kid. Something you can hold in your hands and call your own — made with audacity and passion by The Usual Gang of Idiots.