A capsule history of alternative Japanese comics from the 1950s to the mid ’70s might go like this.

In the beginning, there is Tezuka Osamu, of course. In the mid 1940s, he took the language and content of existing Japanese and American comics and synthesized them into what would become the basic shape of Japanese “story manga” in the postwar period. His early single-volume akahon books were some of the immediate postwar period’s top sellers. By the mid ’50s, due to the popularity of Astro Boy and his other work for magazines, Tezuka had become a household name. It is the rare manga author of the period in question that was not weaned on Tezuka, and so he is a major presence in the history of alternative Japanese comics even after his own work was no longer at the vanguard. He was the father figure to be overcome, but also the artist in whose work the way to the future was always already to be found. As both author and publisher, he was also a direct player in this history until the early ’70s.

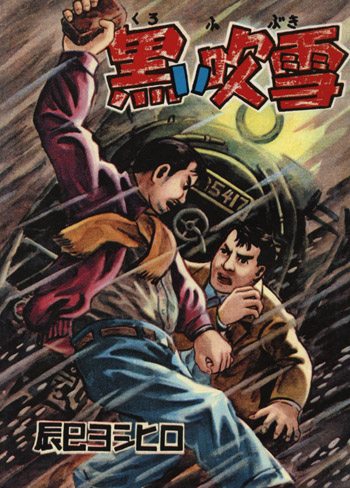

It is mainly in the 1950s that alternative Japanese comics can be understood as an alternative specifically to Tezuka. In the mid ’50s, a group of young artists in Osaka, working in the context of rental kashihon comics, began to object to the model of existing children’s comics. They saw a field dominated by frivolous slapstick, an over simplistic division between good and evil, and flights of fantasy at the expense of contemporary Japanese actuality. For something new, they turned to the psychological dramas, moral ambiguities, and violence of contemporary detective fiction and suspense films. One of this group, Tatsumi Yoshihiro, eventually gave this new genre of adolescent comics a name that stuck: “gekiga,” meaning “dramatic pictures.” In 1959, leading authors of this new genre formed the Gekiga Studio, an artist-run publishing collective based on profit-sharing and editorial control, with a view ultimately to self-publishing. The organization was short-lived, disbanding after just six months, but the influence of the work produced under its banner was great.

Though first developed in the context of the rental kashihon market of Osaka, by the late ’50s the language of gekiga had already begun to show itself in the mass print magazines coming out of Tokyo. Begrudgingly, the old master Tezuka first tried his own hand at the genre in 1959, and traces of its influence remained permanently in his work. By the mid 1960s, the paneling techniques and themes of gekiga had become the lingua franca of most comics for adolescent males, and by the end of the decade the name “gekiga” had become more or less synonymous with comics for adult men as well, as long as they weren’t too cartoonish or dominated by humor. The situation was such that, toward the end of 1967, Tatsumi was compelled to write Gekiga College, an attempt to set the record straight and reclaim gekiga from the culture industry. The book was highly influential, and became a foundational text for the critics of the small self-published coterie magazine Manga-ism, founded in 1967. It was they, circa 1970, who first framed Tatsumi and kashihon gekiga as the beginning of an “alternative” comics lineage and an authentic popular cultural expression of the pre-high economic growth '50s.

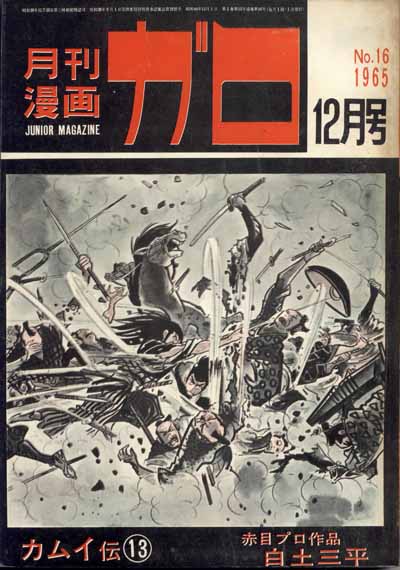

Ironically, the original goal of the Gekiga Studio and its artists had been strongly commercial. Statements from the period make it clear that one of their central desires was to create a comics genre on par with the leading mass entertainment media of the day, namely television and the movies. It was not a community particularly concerned with social or political issues, or using comics to address them. In this too, Tatsumi and the Gekiga Studio diverged from Tezuka, who regularly mixed edification and entertainment throughout his career, beginning with antiwar and antinuclear messages in his work from the late ’40s and ’50s. In the late ’50s, a number of kashihon authors – some working within the broad genre of gekiga, others in burgeoning girls comics – likewise began to take up explicit social and political issues. This ranged from the legacies and traumas of World War II, to issues of labor and class in contemporary Japan. Foremost amongst this contingent was Shirato Sanpei, who dealt with themes of class struggle, economic exploitation, and racial discrimination in stories typically (but not always) set in the premodern period, culminating in The Legend of Kagemaru (1959-62), a sixteen-volume epic about the civil wars and peasant uprisings of the sixteenth century. Shirato’s aggressive left-wing perspective, fulminations against social injustice, and images of armed revolution marked a departure from the more generalized pacifism of Tezuka’s worldview. The Manga-ism critics naturally gave Shirato a privileged place in their history and theory of kashihon manga, but they always seem uneasy about the ideological didacticism of his comics. More engaged with Shirato’s politics were progressive intellectuals and college students: their many essays about his work from the mid and late ’60s form the first sustained body of manga criticism. They also introduce the idea that comics could occupy an important position within a political counterculture.

In 1964, Shirato and publisher Nagai Katsuichi founded the monthly Garo. Though beginning as a left-leaning activist publication dedicated to politicizing children against reactionary government, it also served as ark for what was understood to be a dying kashihon spirit of free expression and populist cultural authenticity. On both fronts, Garo pitted itself against the growing dominance of the mass print manga weekly. Here again, 1959 was a turning point in the history of Japanese comics: The first two manga weeklies, Youth Magazine and Youth Sunday, appeared that year. Their popularity grew quickly, changing the face of the industry. By 1964, the per-issue print-run for each had crossed 300,000, and by 1968, one million. Meanwhile, the kashihon market had all but collapsed, and many of its authors vanished with it. Others survived in various ways. Some became the biggest names of ’60s mainstream manga, like Saitō Takao, a founding member of the Gekiga Studio. (It was largely against Saitō’s version of “gekiga” that Tatsumi wrote Gekiga College.) Some flourished without joining the culture industry, thanks in large part to Garo.

Representative of this latter group was Tsuge Yoshiharu. He had been a central figure in kashihon publishing in the late '50s, but his career had begun petering out with that market in the early ’60s. Then Shirato and Nagai invited him to publish in Garo. His dozen-plus stories for the magazine between 1965 and 1970, typically starring a lone sole-searching male traveler, quickly became standard bearers for literary comics in Japan. In one of the first issues of Manga-ism, a writer declared Tsuge’s “The Pond” of 1966 a revolution in the language of gekiga. When “Nejishiki” appeared in 1968, a modernist poet upheld the surrealist story as the beginning of “art” in manga. When Tatsumi remade himself in the late ’60s as an author of seedy stories of Japanese masculinity in crisis, it was Tsuge’s Garo work that was his model. And the image of Tsuge himself – unkempt in the early ’60s, a wanderer in the late ’60s, and poor and clinically depressed throughout – became an icon of the struggling manga “artist.”

While supporting older artists, Garo was also instrumental in nurturing a new breed of manga-makers. Following the example of kashihon anthologies previous, in its June 1965 issue, Garo published an open call for new talent. What followed was some of the most innovative and unconventional work in Japanese comics history. In 1968, the young twenty-three-year-old Hayashi Seiichi began experimenting with the language of nouvelle vague. In the same year, Sasaki Maki, an art school dropout, began making wordless, non-narrative comics inspired by contemporary rock album graphics and Pop Art. In 1971, Abe Shin’ichi started publishing works about bohemian life in the western Tokyo neighborhood of Asagaya. And there were numerous crossovers with the wider counterculture. Shirato’s The Legend of Kagemaru was made into a movie by director Ōshima Nagisa in 1967. Also in 1967, the experimental Jiyū Gekijō theatre troupe based a play on Shirato’s Akame (1961). A cinema verité experiment shot in 1968 took the tile of “Nejishiki.” Hayashi, while publishing in Garo, also designed sets and posters for angura theatre groups and films. His masterwork “Red-Colored Elegy” (1970-71) about a young couple struggling with art and love inspired first a hit folk song in 1971 and then an independent film in 1974.

Garo itself inspired a number of magazines. Most important of these was COM, inaugurated by Tezuka Productions in 1967. Its impact on the course of Japanese comics has been no less than that of Garo, though of a very different sort. Though, like Garo, seeking to cultivate experimental form and new talent, COM was unique in its particular commitment to amateur manga circles. The bulk of its pages were given to Tezuka’s grandly planned “The Phoenix.” Ishinomori Shōtarō’s near-wordless fantasy “Jun” was meant to show that COM would not be outdone when it came to experimentation. Nagashima Shinji’s stories about hippies and artists in Tokyo, whom he had been writing about since early ’60s kashihon, would not have been so popular had the magazine not been read by so many young aspiring manga authors. One thing that distinguished COM was its female authorship and readership, including shojo stalwarts like Yashiro Masako and Hagio Moto. Garo, in contrast, was narrowly male and conservatively masculine, and stayed that way until it folded at the end of the century.

The greatest contribution of COM to comics history was Grand Companion, at first a reader’s letter page about amateur fan communities and then an independent insert introducing new talent, like Okada Fumiko and Miyaya Kazuhiko. It was also individuals involved with the amateur circles around Grand Companion that went on to establish the “Comics Market” in 1975, the “manga fanzine fair” that began as a one-day, one-room annual gathering for about 700 people, but has grown today into a twice-yearly, three-day extravaganza for the small-city equivalent of 500,000. From there, back to the open calls for new talent in the pages of Garo and COM in the latter ’60s, and further back to the cartooning contests of Manga Shōnen in the early ’50s, where Tatsumi and other kashihon stars published their first works, the history of alternative comics in Japan is intimately tied up with the status of the “amateur” and the de-differentiation between fan and professional, artist and critic, commercial venture and private self-expression.

In this history of alternative Japanese comics, it is important not to forget the mainstream. In the late ’60s, divisions between mass entertainment and counterculture, or between mainstream and alternative, were never so clear. The viability of Garo in the ’60s had to do in large part with the widespread popularity of Shirato’s work, whose production studio was also drawing stories for Sunday and Magazine, and whose comics were made into animated television series and movies. Likewise, COM could not have existed without the capital of Tezuka Co. And while some of Garo and COM’s offspring remained perpetually minor, a healthy number took their innovations to mass publication.

The view from the mass weeklies offers a similarly scrambled view. There was a saying from the late ’60s, meant to capture the cultural formation of the Japanese university student, who at that point was often caricatured as running around in a helmet fighting Japanese authority with a wood plank and anti-imperialist slogans. It goes, “Journal in the hand, Magazine in the heart,” referring to the popular left-leaning weekly opinion magazine Asahi Journal, and the by then 1.2-million-weekly print-run Youth Magazine. The success of the magazine had much to do with its ability to grow with the baby boomer generation, addressing sporting schoolboy tastes at its founding in 1959, adolescent curiosity for the queer and grotesque in the mid ’60s, and the world of countercultural cool and adult sexuality by the end of the decade. It was Magazine, more than any other publication, that was responsible for making Japan (for a time) into a country of manga readers.

Mass marketability, however, did not preclude experimentation in form or content. Some of the most striking innovations in paneling, and some of the edgiest subject matter, were to be found in the pages of Magazine. Its overall design and layout were likewise on the “cutting edge,” and for a few months in 1970 the magazine hired the graphic designer of the counterculture, Yokoo Tadanori, to do its covers. And as Magazine pursued the counterculture, so the counterculture went in droves to it. Its popularity amongst students, it was said, was due to its underdog heroes, and the pervasive violence and nihilism, thought to capture the zeitgeist of an age of broken political struggles. In March 1970, poet, playwright, and filmmaker Terayama Shūji organized a mock funeral for Riki’ishi Tōru, one of the magazine’s beloved fighters, killed with a freak hook to the head in the wildly popular boxing title, “Tomorrow’s Joe.” And a week later: members of the Red Army, a radical splinter group of the late ’60s student movement, commandeered a Japan Airlines flight to North Korea. Before departing from Tokyo, one of the group declared to the press: “We are Tomorrow’s Joe” – meaning that they’ll fight however ragged to the finish.

Given all this, one might justifiably ask, how much sense does it make to speak of “alternative manga” at all? For example, one thing often raised to argue the outsider status of kashihon gekiga was its persecution as vulgar and degenerate by PTA groups and the government in the latter half of the 1950s. But it is interesting that just as this was becoming a piece of “alternative” lore amongst the Manga-ism critics, certain comics in the mass print weeklies – namely George Akiyama’s “Ashura” (Youth Magazine, 1970) and Nagai Gō’s “Shameless Schoolyard” (Youth Jump, 1968-72) – were being lambasted for the same distastefulness and corruption. By the early ’70s, Garo had begun to deliver some pretty nasty things, but by that point vulgarity – like formal experimentation and nonconformist politics – could be found just about anywhere. “Alternative” might have meant something in the ’50s or ’60s, but it’s nearly useless as a compass in finding one’s way through Japanese comics thereafter. Which is to say, just as the idea of “alternative comics” came together as a coherent critical concept in Japan, it could only be reliably applied to the past.

In this column, I want to explore this history in greater detail, focusing in on specific artists, specific works, specific years, specific publications, and specific critical issues. The goal is to progress in a logical fashion, beginning with kashihon gekiga, both as a historical phenomenon as well as its position within alternative manga theory beginning in the late ’60s. That’s the plan, but I am doing research on the history of alternative manga as I write about it, so circumstance and whim will likely take the column in sudden direction changes. Likewise, if there are some ambiguities and contradictions along the way, and some tangents and diversions, please understand that I am still figuring these things out for myself. I am hoping that I will be able to revise and collect what I write here into a book, so comments, questions, and constructive criticisms would be more than welcome.

Why the past tense in the title: What Was Alternative Manga? Partially for convenience, as two decades of material is mountainous enough. Partially because I am more interested in the past of Japanese comics than the present. But also because this period forms a discrete historical period with a number of interrelated narrative arcs: the rise of kashihon gekiga in the mid ’50s, the popularization of the name and language of gekiga in the ’60s, and then the positioning of kashihon gekiga as “alternative” circa 1970; the politicization of comics in the ’50s alongside contemporary social and political movements, and then the almost total withdrawal from progressive politics in alternative manga by the early ’70s; the rapid rise of manga as a mass entertainment medium in the ’50s and its complete normalization as such two decades later; the rise of the amateur as a leading force in comics production beginning in the mid '50s and the institutionalization of amateur production by the mid ’70s.

I am going to start these stories, however, not at the start but nearer the end, in late 1967, when thanks to the work of Saitō Takao in Youth Magazine, gekiga fully enters the mainstream, and Tatsumi Yoshihiro decides it's time to set the story straight with Gekiga College. It is from this point that I think the idea of an “alternative” lineage within Japanese comics begins to gel, even if the creation of alternatives in manga date from much earlier.