Cartoonist Michael Maslin has been contributing to The New Yorker since 1977, and his cartoons have been appearing regularly in its pages since 1978. He’s the author of many books of cartoons, including most recently Cartoon Marriage: Adventures in Love and Matrimony by The New Yorker’s Cartooning Couple, which he co-authored with his wife, cartoonist Liza Donnelly.

Cartoonist Michael Maslin has been contributing to The New Yorker since 1977, and his cartoons have been appearing regularly in its pages since 1978. He’s the author of many books of cartoons, including most recently Cartoon Marriage: Adventures in Love and Matrimony by The New Yorker’s Cartooning Couple, which he co-authored with his wife, cartoonist Liza Donnelly.

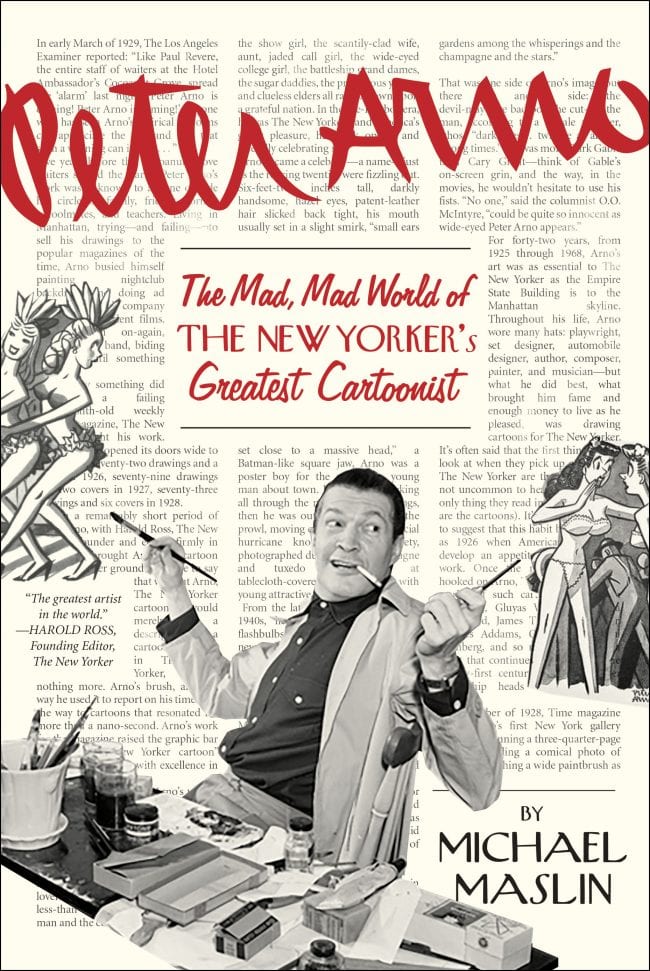

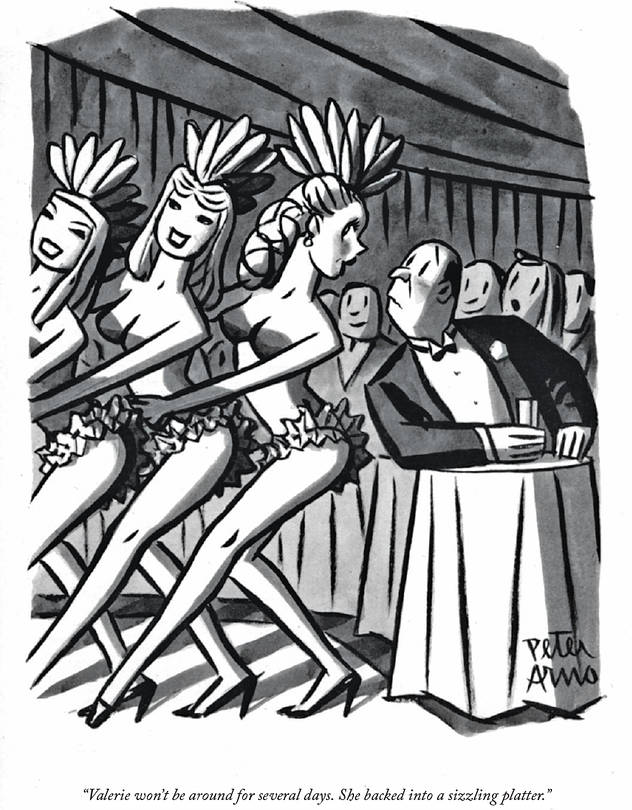

Maslin’s new book is the prose biography Peter Arno: The Mad, Mad World of The New Yorker’s Greatest Cartoonist. To people who have read Maslin’s blog Inkspill, it’s clear that he has a fascination with The New Yorker magazine and its history. In this first full-length biography of Arno, Maslin looks as the man who helped to define the magazine’s look and define what a New Yorker cartoon is.

That vast influence and the shadow that his legacy has cast over the magazine is significant, but as Maslin lays out, it’s only part of the story. Arno had a colorful life and not only did he help to document what became known as “cafe society”–the social scene that emerged among a certain class of people following Prohibition–but he was a part of it. Arno also worked on Broadway, went to Hollywood, got blackmailed, was threatened by a Vanderbilt, dated debutantes less than half his age, and led an atypical life for a cartoonist.

You mention in the book’s afterword that you found an old Arno book at a store and inside was a press clipping of how Arno had gotten arrested. It’s one thing to be curious and look up Arno, but it’s another thing to spend 15 to 20 years of your life, on and off, researching a biography of him.

[laughs] You’re absolutely right. I lay it out there how that happened and I think this is what a cartoonist’s brain does. We soak things in and, at least for me, it sometimes takes years for things to connect. This is why I was a terrible student. That clipping made an impression on me, but it didn’t really take me anywhere other than, oh, that’s really different for a cartoonist. Years later driving along near where he lived it really was like those old Betty Boop cartoons where Grampy has a lightbulb go off over his head when he gets an idea. I was just thinking about cartoonists and then I thought of Arno. I don’t know why it took me so long because I’d been collecting cartoon books and books about The New Yorker for years, but it dawned on me that this major figure hadn’t really been given his due. I’d never written anything longer than a report in school so the idea of doing a biography was a little crazy. I actually started sweating when I was seriously thinking about it, but by the time I got home I was convinced I should do it. First I called The New Yorker and asked if anybody had been asking questions about Arno. They said, no, no one had, and I thought, okay, I should do it.

[laughs] You’re absolutely right. I lay it out there how that happened and I think this is what a cartoonist’s brain does. We soak things in and, at least for me, it sometimes takes years for things to connect. This is why I was a terrible student. That clipping made an impression on me, but it didn’t really take me anywhere other than, oh, that’s really different for a cartoonist. Years later driving along near where he lived it really was like those old Betty Boop cartoons where Grampy has a lightbulb go off over his head when he gets an idea. I was just thinking about cartoonists and then I thought of Arno. I don’t know why it took me so long because I’d been collecting cartoon books and books about The New Yorker for years, but it dawned on me that this major figure hadn’t really been given his due. I’d never written anything longer than a report in school so the idea of doing a biography was a little crazy. I actually started sweating when I was seriously thinking about it, but by the time I got home I was convinced I should do it. First I called The New Yorker and asked if anybody had been asking questions about Arno. They said, no, no one had, and I thought, okay, I should do it.

It took 15 years because I had never done anything like this before and I had to learn. It was one of the best experiences of my life. It took me a long time to figure out how to research. The afterward is actually the very first thing I wrote. I got into it really fast and the more I wrote, the more information I needed. I think I became a bit obsessive about everything in his life. I was constantly going off on tangents. I don’t know if I’ll ever find anything like that again. It was like a drug I suppose–in a good way. It’s very different from cartooning and maybe that’s why I loved it so much. This morning I was sitting here and I did three drawings and each drawing is its own little world and then you put it aside and do something completely different. With Arno, you stay the course and you have to stick with the subject and figure things out and try to understand what’s going on. I just found it fascinating.

When people ask you, 'Who was Peter Arno?' what do you say?

When people ask you, 'Who was Peter Arno?' what do you say?

I actually haven’t been asked yet, but I’ve thought about who he was. I’ve been prepared for something like that. I don’t know. I don’t even know who I am. [laughs]

Okay, now this conversation feels like a New Yorker cartoon. [laughs]

I’ve taken stabs at thinking about what he was like. I think it was helpful that I am a cartoonist writing about a cartoonist. We had a little similarity in where we began. We both started in our early twenties. He didn’t finish college but I finished and started right away at The New Yorker, or pretty much. He did have a job or two, but I can understand being that age and getting into The New Yorker. Of course when he got into it, as you know, it wasn’t “The New Yorker” yet. I can understand how in a way he became his own man very quickly. He became successful very quickly. He started in June of ’25 and by somewhere in 1926 he was becoming a star and by the end of the twenties, he was a star. He was able to do the cartoonist life as I have been able to. He didn’t mind challenging Harold Ross at all. He could draw what he wanted to draw. He went off and took breaks when he wanted to. He traveled. I think he just really really enjoyed life. He didn’t have the experiences that a lot of young people have, working in an office in his twenties and figuring out what he wants to do. He just had that a tiny bit when he worked for Chadwick Pictures but that was just a year.

Who was he? He was a guy who really took advantage of the situation he was in. He was very very lucky that he had Harold Ross in love with him and his work. It just came together beautifully for both of them and for the magazine itself. I’ve learned from various parties that he did have an attitude, but maybe that comes from being your own boss for so long and becoming quite popular and in demand so quickly. He said in his unpublished memoir, “I go around thinking that people like me.” He seemed to be an affable fellow–unless you were trying to steal his date or something like that. I think he just enjoyed being alive and being Peter Arno.

When Arno began, was his style jarring compared to what was typical? What distinguished him early on?

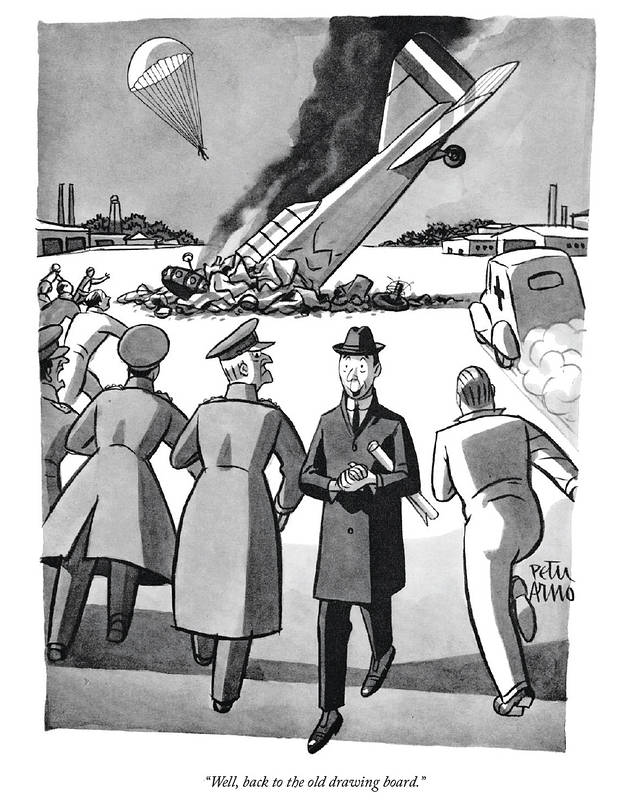

What most people remember as a Peter Arno drawing was a style that came much later, in the later thirties and the forties and fifties. When you think of a Peter Arno you think of a very simple–not simple like Thurber simple–but a very clean, dramatic look. As you see in the book the earlier drawings are clean and they are dramatic but they’re not bold like the later drawings. One of Arno’s heroes was Honore Daumier. If you look at Daumier’s drawings, you’ll see they’re very fluid.

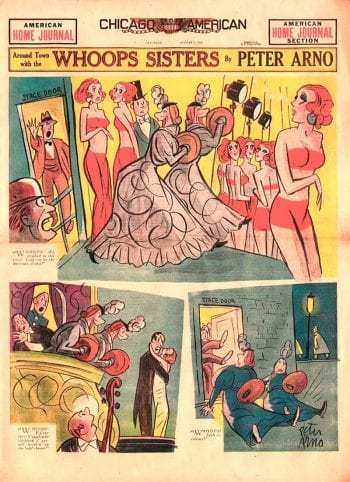

Arno’s later drawings have this very strong look but the earlier drawings are more lovely, I think. The drawings have sway to them and flow and then as you get closer to the end of his life, the lines get straighter, there’s less flow. There are some curves of course, for the women, but there’s a big difference between later Arno and earlier Arno. The drawing style in his early drawings weren’t that different from other drawings first appearing in The New Yorker. The early ones weren’t shocking in look. The content and the subject matter and what he was saying with the Whoops Sisters was possibly shocking. I don’t know because I wasn’t alive in ‘25, ’26, but I have a feeling that people were thrilled that they could pick up this magazine and see these old ladies talking somewhat dirty. I talk in the book a lot about cafe society, a branch of society that people aren’t all that familiar with these days. Arno was drawing it, and living it. It was more the subject and the content than the actual drawing itself at that very early point that got the reader’s attention. I think his work as a whole really gelled as he got better and the idea people started coming in stronger and stronger. When I first started the book, The New Yorker gave me a print-out of almost all his work. You can go through it and see the development of the captions from these casual not tremendously written things to these more precise captions and that’s probably due to the advent of the gag men into his life.

Arno’s later drawings have this very strong look but the earlier drawings are more lovely, I think. The drawings have sway to them and flow and then as you get closer to the end of his life, the lines get straighter, there’s less flow. There are some curves of course, for the women, but there’s a big difference between later Arno and earlier Arno. The drawing style in his early drawings weren’t that different from other drawings first appearing in The New Yorker. The early ones weren’t shocking in look. The content and the subject matter and what he was saying with the Whoops Sisters was possibly shocking. I don’t know because I wasn’t alive in ‘25, ’26, but I have a feeling that people were thrilled that they could pick up this magazine and see these old ladies talking somewhat dirty. I talk in the book a lot about cafe society, a branch of society that people aren’t all that familiar with these days. Arno was drawing it, and living it. It was more the subject and the content than the actual drawing itself at that very early point that got the reader’s attention. I think his work as a whole really gelled as he got better and the idea people started coming in stronger and stronger. When I first started the book, The New Yorker gave me a print-out of almost all his work. You can go through it and see the development of the captions from these casual not tremendously written things to these more precise captions and that’s probably due to the advent of the gag men into his life.

You make the point that while he wasn’t a joke person, he didn’t even illustrate jokes especially well, he excelled at being a storyteller in a single panel in a way few people can do.

He considered himself a reporter. He did have a camera at some point. I’ve never found any photographs that he took but I’ve read that he sometimes would take a camera to nightclubs for research so he could be more accurate. I don’t know which drawings reflect that. I have a feeling that he spent enough time in these places that he didn’t really need to take photographs. [laughs] What do cartoonists do? They soak up images. I think he was probably fairly accurate drawing a lot of things he was seeing.

It’s not like Arno arrives in 1925 and cartooning changes. It was nothing like that, but a lot of the early drawings and comics I’ve looked at from the late 1800s and early 1900s are very dry. You need a great microscope to find the humor in a lot of these. We weren’t living then so maybe people back then found them hysterical, but today most of them seem really not funny. I think that’s why when Arno came along he was almost an early version of People magazine or TMZ. He was giving us some really interesting insights into a part of that culture that people were beginning to be fascinated by.

Fairly or not, I’ve always associated a lot of Arno cartoons with this segment of New York like in The Thin Man or Fred Astaire movies.

That was early cafe society, which then became something else. I say a number of times that he was really tired of it by the time he got into the mid-1930s because it had changed into a different scene. It became more like the club scene in New York. Once everybody knows where the cool place is, it isn’t cool anymore. Cafe society started in the teens so Arno came a little late to it. By the time he got to it it had morphed into this really fascinating scene of dance clubs and the people with cigarette holders and all that. Arno hit at just the right time. He wasn’t a really wealthy guy but he had a little money, some fame, and they accepted him. Like Truman Capote who got to hang out with people far more wealthy than he. Arno was comfortable with them but at the same time he really didn’t like a lot of them. As I quote him saying in the book–the book was originally going to be called Mad at Something–“You don’t do good work of this sort unless you’re mad at something.” He really didn’t love the upper crust and the privileged. Even though he was among them, it seemed they really pissed him off. [laughs] He used his pencils and his brushes to work that out–lucky for us.

You point out in the book that every few years he would give an interview saying the scene isn’t what it used to be, I’m tired of it, I’m going leave Manhattan–and then five years later give the same interview to another publication.

You point out in the book that every few years he would give an interview saying the scene isn’t what it used to be, I’m tired of it, I’m going leave Manhattan–and then five years later give the same interview to another publication.

It was probably like a drug to him. He was a Manhattan-born boy and he was very comfortable there but when he did leave, he was mostly happy. It took a while. It was just a case where he had to be really tired of the scene and by 1950 he had had it, it seems. Living north of Manhattan he seemed to be quite a happy man. He drank too much at times but I think that was part of the culture then, too. You’ve seen Mad Men. But you’re right, he kept saying I’m going to leave one of these days and then he finally did. But he didn’t go far.

Arno wasn’t just a reporter of the scene, he was part of the scene. He played the Sun King, with 48 debutantes playing his ladies in waiting. He was in his thirties and forties and dating 17-year-old debutantes. He’s mocking them, but he’s also one of them.

It must have been odd for him, I would think. Maybe we’ve all been in that position at one time of another: I’m enjoying this, it’s interesting, but I hate it, too. I have a feeling that happened to him a lot. Yeah, the Velvet Ball, where he was up on a throne with all those women parading in front of him–including his soon to be girlfriend, Brenda Frazier–that was something. I mean he was a cartoonist so he had that side of him where I think he would do some fun things. He didn’t seem stuffy at all.

There was an article that called Arno America’s most tabloid friendly cartoonist, and I know a lot of cartoonists and there’s not a lot of competition for that title.

[laughs] It was a good thing and a bad thing for research. A good thing because you know there’s a lot of material out there but a bad thing because I was seeing the same stories over and over again. They just use the same words. I mean who would be the contemporary version of tabloid-friendly? That’s why when I read the clipping of Arno with the gun, it was like, are you kidding me?

Arno is not like most cartoonists.

No. Most cartoonists don’t go to Hollywood. Most of them don’t write plays.

Most cartoonists don’t go to Reno to get a divorce and then start fooling around with a married woman who’s there with her husband.

[laughs] There was a lot of color in his life and I think that’s what attracted me to him. People have asked me, are there cartoonists you would want to cover next? There are a lot of cartoonists whose work I absolutely love, but I have a feeling that they were home all the time drawing. They weren’t out getting into trouble or causing mischief that the tabloids would pick up. Arno’s life was as appealing as the work. They go hand in hand.

Arno wrote an unpublished memoir but he wrote few letters and had few papers. How do you research someone like that?

The first thing I did was find everything I could that had been written about him and I used these things as clues. There was a series of books called Current Biography. They’re just short pieces about famous people. They have an entry for Arno in 1942 and it’s maybe two or three pages, but they put a lot of information in there. I think that was the point of these things. It wasn’t just somebody talking about Arno, they researched him and at the end they list their sources and that was almost my blueprint. I began with that; there would be a quote from him that he said something or other to Joseph Mitchell so I had to find where the rest of that interview was.

I will say the one thing in that Current Biography that I never found–and it was repeated in other places: he cracked Tin Pan Alley with a song “My Heart is on My Sleeve.” I can’t tell you how much time I spent trying to find this. I searched the Billy Rose Library in New York City, I contacted music publishers, I went to the Library of Congress, I talked with sheet music experts. This song, if it cracked Tin Pan Alley, I don’t know how it cracked it, or when or where or what it sounded like.

A fellow visiting our house recently peaked into a room in our house and he said it looked like a scene from A Beautiful Mind. Since I had no experience with gathering information, I put a timeline up on the wall and I would fill in things that I found. I filled three of the four walls in there and it did look a little nutty, but it was very helpful for me to sit at the desk and look up and gauge what happened when and what else I needed to look into. It was a fascinating experience learning how to do this. A lot of it I found before the internet got as great as it is now. [laughs] For example, the New York Times now, if you’re a subscriber, allows you to search anything that has ever appeared in the New York Times. Well back when I began the book that service was not available and so I had to use microfilm.

I wanted to ask about Arno’s stolen car cartoon because in 1929 when it was published it was controversial and really divided people at the magazine about Harold Ross.

I do spend a little time on that because it’s an interesting dividing line. It created these two camps: did Harold Ross know what this cartoon meant or didn’t he? According to Thurber, Ross said the cartoon had an Alice in Wonderland quality to it and it wasn’t about sex, it was just an interesting drawing. I assume t hat drawings are selected sometimes because the editor sees them as something other than the artist does. I don’t know if that’s really true in this case. I love the drawing; I think it’s a beautiful drawing. It’s definitely about sex. Why else would they just have the back seat?

hat drawings are selected sometimes because the editor sees them as something other than the artist does. I don’t know if that’s really true in this case. I love the drawing; I think it’s a beautiful drawing. It’s definitely about sex. Why else would they just have the back seat?

It’s obvious what it is, but what was almost more interesting to me is this division it created. The E.B. White camp on one side saying Ross did know and the Thurber camp on the other side saying, no, he didn’t know. The Thomas Kunkel biography lays it out pretty well that Ross was prudish about sex. I lean towards Ross thinking it was an Alice in Wonderland type of thing. Look at the Whoops Sisters. In the book I say that Ross thought they were too rough but he brought the sketches home and showed his wife who said these are great, you should run them, and then they became possibly the savior of the magazine. It’s an interesting drawing for many reasons. One it’s just a beautiful drawing that looks great. Now we’d probably think it’s very innocent -- y’know, so what --they were out in the woods fooling around, but back then it struck a nerve in the magazine and with the readership.

It’s funny because today it does have an Alice and Wonderland surreal quality to it and does in an odd way reads as much less sexual than it did then.

We’ll never know, but I love the idea that it caused trouble. How often does that happen? Are you familiar with Jack Ziegler’s work? When he started at the magazine in 1974 he was really different. He was the beginning of this new school, the National Lampoon-Mad Magazine inspired school. William Shawn was buying his work but it wasn’t appearing in the magazine. After a while Jack called and asked, where’s my work? They checked and the guy who laid out the magazine didn’t like Jack’s work and so he wasn’t putting it in the magazine. Of course William Shawn as the editor got his way and Jack became one of our greatest modern cartoonists.

You started contributing to The New Yorker in the late 1970s, and that was a decade when there seems to have been this major generational shift. Jack Ziegler, Roz Chast, Gahan Wilson, Leo Cullum, Bob Mankoff. I’m curious, was there a sense that this new generation–Ziegler and Chast especially–were doing something different?

They were. There’s a four-year difference between Jack [Ziegler] and Roz [Chast]. Roz started in ’78. Jack appearing, four years earlier, was directly the product of Lee Lorenz, who had just taken over from James Geraghty. Lee took over in ‘73 or ‘74 and he was actively infusing the cartoon world with new work–just as Bob Mankoff is doing today. Lee said that when he came in a number of the cartoonists were aging and a lot of them were relying on gag men–he could see the writing on the wall. I think he was also reacting to the times. By the mid seventies it was a different world. I don’t think people wanted to see businessmen chasing secretaries around anymore. We’d been through the sixties and all the underground comics that came out of that period like Robert Crumb; things were changing. Lee was smart enough and wise enough to introduce this new kind of cartoon to The New Yorker and William Shawn–god rest his soul and god bless him–said yes to this.

It worked out extremely well and following Jack we had this whole wave coming in around the same time I did. Bob Mankoff and all the people you mentioned. It was very exciting. I felt that we were the kids. I didn’t feel like I’d ever reach the heights that these great masters had reached. A lot of them were still there. Charles Addams–one of my heroes–was still publishing when I was there. I was just happy to be there. I think we all felt that way. The real guys–the General Motors of the cartoon world–they were doing it and we were taking part in it. I was glad to have met some of these guys and to correspond with them. I think Jack did influence and open things up. Roz is a world unto herself. She’s got her own thing going; just like Thurber did. Charles Addams, I think, led to other people like Gahan Wilson and some others in that school like Zach Kanin. There’s no heir to Roz at the moment. And that’s fine. There’s only one Steinberg.

You mentioned in the book that your earliest sale to the magazine wasn’t a cartoon, it was the gag in a cartoon which was given to another artist. Arno and Charles Addams and many other cartoonists worked like that. Could you talk a little about how that worked?

Arno wrote the forward to a collection of his celebrating his 25 years at the magazine called Ladies and Gentlemen. It’s one of my favorite collections of his and he talks about [gag writers] very openly. He said the first few years it was all his own work. I don’t know how you define “first few years” and since the New Yorker lost 72 boxes of material when they moved that one time, I don’t know either. The environment at the early New Yorker was that the editors, the fiction editor, Katharine White and Ross himself and Rea Irvin would sit in the room and they would manage the art. They would sometimes match captions to art. If somebody sent in a caption they would decide the caption would work better with another person’s art. Or they would come up with captions. This is not to say that there weren’t people sending in cartoons with captions that were then published as they sent them in. That happened as well, but there was a lot of communal work going on as far as the art.

Arno became so popular. For the first few years he was being published 70-80 times a year. There’s no way he could have done that much really good work. He said he needed help so he started to rely on the idea men and that reliance increased as time went by. By the '40s and '50s he was really reliant on them. Especially Richard McCallister, who I put a spotlight on because he deserves it. You can go to the New York Public Library and look at McCallister’s papers and get lists of the ideas he provided for Arno–they’re great ideas. That was the culture. A lot of the people that came into the magazine in the twenties and thirties and forties were just great artists who needed help all the time. As I lay out in the book, the guys who came in in the fifties and sixties like Ed Fisher and George Booth and Ed Koren all did their own ideas. By the time Roz and Jack and Bob Mankoff and I came along, we didn’t even know that people weren’t doing that. It was unthinkable to us. So when the magazine asked, can we use this idea for Whitney Darrow, I was like, what? I don’t understand. That was an education for me.

About four years after that, in the early eighties after I’d been published for a while, Lee Lorenz called me and asked, can we give this particular drawing to Charles Addams? I was like, oh my god, yes. He did a beautiful job–much, much better than my drawing. [laughs] The funny thing is when Addams died the Newsweek obituary mentioned this drawing and said it’s a brilliant Addams miniature–which makes me feel good and odd at the same time. [laughs] He was a brilliant. The drawing I submitted, graphically, was nothing like his. Jack Ziegler gave him ideas, Leo Cullum gave him ideas, Peter Steiner have him ideas. I think it was very nice of the magazine. They wanted Charles Addams and some other people to continue publishing and if that meant supplying him with ideas, great. It was a system that died but hung on just a little bit.

Has the practice of using gag writers mostly died out?

I actually wrote a piece on my site on collaborations, which have come back. Some of the newer people actually sign the name of the person that wrote the idea. There are just a few. Kate Beaton and Sam Means, for example. The cartoon would be credited “Beaton and Means” so it was right out in the open. There are several cartoonists now who openly use idea people. Then there are people who are shy about telling people about it. Whatever they want to do --it’s their life. Our little crew still holds fast to the idea that it seems unthinkable to use other people’s ideas; it becomes a different thing then. As far as I know Roz and Jack and Bob and my wife, Liza Donnelly, we just rely on ourselves.

You end the book by asking dozens of New Yorker cartoonists about Arno’s work and influence and why did you decide that this was where to end the book?

I’m a huge fan of the New Yorker’s history. Obviously. Part of the reason I wanted to do the book, I was sort of afraid that Arno’s work would drift away in the national consciousness. He was too important for that to happen so I felt like–I said this to his daughter–I needed to give him his due. As best I could anyway. I wanted to do my part in helping his name and his work continue on. That led me naturally to think, what did I think of Arno’s work, and I wrote about that. Then I thought, what about everyone else? I have a lot of colleagues and at the time I started the book, people like William Steig and Syd Hoff and Mischa Richter were still alive and they were contemporaries of Arno’s and I thought, ask them what they thought of him. I knew that people coming in like Liana Finck didn’t know Arno personally but I thought wouldn’t it be great to know what they thought–whether positive or negative. I said in my letter to all of them, this isn’t a valentine, tell me what you think. Did you like his work? Did you hate his work? Did it mean something? Did it mean nothing? I left it wide open because I was curious how much influence he had and what his legacy was.

I was really surprised, in the best way, that so many of the newer cartoonists really knew his work and it meant something to them. Even if it was just the idea of him, like, that’s what a New Yorker cartoonist is. Others were more specific about the way he drew and that this is something that meant something to them. Some people of course said, he meant nothing to them. I wanted that, too. I wanted to grab everybody I could at this period of time and I was lucky enough to talk to some of the fellows who were Arno’s contemporaries. I was also fascinated to learn what the new people thought. Some people told me, I have nothing to say. If they’re not there in the book they either had nothing to say or they missed the deadline.

You joked earlier that when you decided to write the book, you hadn’t written anything but since then you started your website Inkspill, where you’ve written a lot about The New Yorker and cartoonists.

Inkspill began simply because everyone was having their own website. So I made one and then within a week I went, this is boring. I was really tired of just casually hearing that someone had an opening or that they had a book coming out and I thought, what if I made a bulletin board of what people were up to? That’s how it began and then out of that came the historical parts.

There’s something I have called the One Club. It’s eighty or ninety people who have only been in The New Yorker once. It’s curiosity really about cartoon lineage and it’s not just the past but the present. I love meeting the new people who come in and learning about them and who they are. Liana Finck is a fabulous new addition to the magazine. I love her work. Will these cartoonists become the next Roz Chast or Charles Addams? We’ll see. The New Yorker’s not the easiest place in the world to continue on in but I can’t wait to see what happens with them.