For anyone who has ever been frustrated by the insularity, boosterism, and self-congratulatory enthusiasm of comics and comics studies, Marc Singer's new book is a relief and a joy.

For anyone who has ever been frustrated by the insularity, boosterism, and self-congratulatory enthusiasm of comics and comics studies, Marc Singer's new book is a relief and a joy.

Breaking the Frames: Populism and Prestige in Comics Studies is scholarly in tone, rather than polemical. Singer is no Gary Groth—but in his own quiet way, he's arguably more thoroughgoing in his decimation of comics shibboleths, and comics fans and scholars' self-satisfaction. From superheroes to alternative comics, from Ware to Satrapi, Singer mercilessly points out all the emperors without clothes, and every sacred cow that is actually a bunch of chickens in a frayed cow suit. As Kim O'Connor wrote on Twitter while reading the book, "Halfway through the intro and Marc Singer has already politely excoriated: Jill Lepore, G Willow Wilson, his entire field, a professor who I intensely dislike, terfs, Chris Ware, Hillary Chute, and Art Spiegelman."

Singer's anti-idolatry is not performed in the name of iconoclasm itself. Rather, he believes that with a bit more skepticism, comics scholarship, and comics, can be better. Comics critics and fans have been hunkered down in a defensive crouch for too long, half-terrified and half-resentful of the academy's disdain. As a result, team comics, or team comix, has often tried to paper over comics' failings. In one telling example, Singer points out how Hillary Chute skipped over some of R. Crumb's sexist comments when she wrote about his appearance at a 2012 University of Chicago symposium in Critical Inquiry.

But, Singer argues, if we really love and respect comics, we should be willing to hold them, and ourselves, and our scholarship, to higher standards. "We don't have to view our scholarship as either a heroic struggle or a leisurely pastime," Singer says, "just as a responsibility to maintain the highest standards and social purposes of our respective fields." I talked to Singer by phone about his book, how to read comics better, and his hopes for comics studies.

Noah Berlatsky: I guess the first question is, why so negative? Your book is pretty much all about the problems with superhero comics, the problems with alternative comics, the problems with Persepolis, the weaknesses of comics critics from Hillary Chute on down. Isn't it self-defeating for comics critics to dump on comics and comics studies in this way?

Noah Berlatsky: I guess the first question is, why so negative? Your book is pretty much all about the problems with superhero comics, the problems with alternative comics, the problems with Persepolis, the weaknesses of comics critics from Hillary Chute on down. Isn't it self-defeating for comics critics to dump on comics and comics studies in this way?

Marc Singer: I don't think it is any more.

I can see an argument that maybe at one point it would have been when comics still had a hard time gaining institutional acceptance a couple of decades ago. I could understand why somebody would say, "All right, I have to make a case for the best of comics in order to justify teaching a class on comics, or publishing in an academic journal." You're probably not going to open that door by talking about the failings of the medium you're working in.

Although that being said, when I went back and looked at some of the historical criticism, I noticed that—like Umberto Eco wasn't afraid to do that. He was willing to talk about the narrative stasis that comics in the '50s and early '60s were creating. And he wasn't shy about criticizing them. And obviously that piece ("The Myth of Superman") became canonical.

I understand why a generation or so ago scholars might have felt like they would have been undermining their own work or undermining their attempt to find an institutional place for studying comics in the academy. But now, especially after the last decade or decade and a half, there's been so much work done, and there's so many new venues, and comics has achieved so much more critical stature, that I think they can bear the weight of criticism now in a way that arguably they couldn't before.

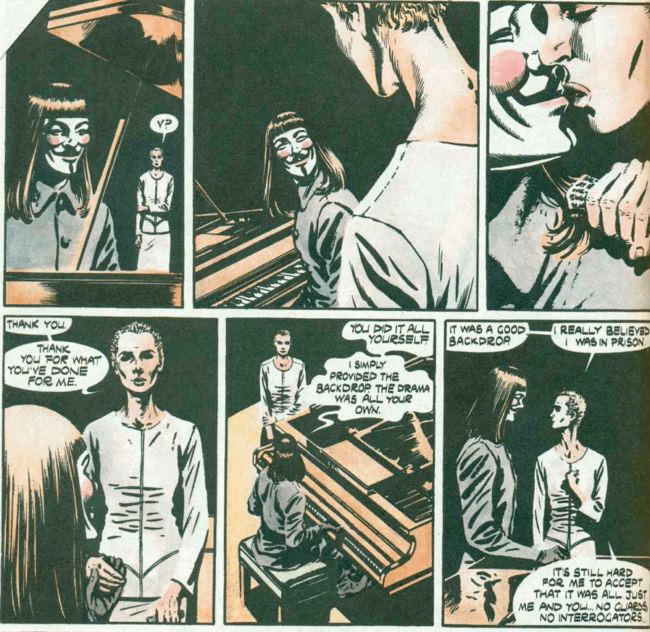

You argue that critics are often too quick to read in a critical stance or a critical perspective in the works they write about. So, for example, to use an example you don't directly address, people argue that V in Alan Moore and David Lloyd's s V for Vendetta is a repudiation of terrorist violence, rather than a glorification of it. Why do people want comics to have a critical perspective? And why are you certain in some cases that they don't, when so many other readers see that in them?

To the first part of the question about why people, I think that it becomes a passport to intellectual credibility for the comics themselves.

There's a common formula in criticism, not just in comics criticism by any means, where if you can show that the work itself is participating in a kind of cultural critique, then you've justified its place in the academy, you've justified its place in the academic journals. And you've justified your own work, because essentially at that point all you need to do is draft along behind it, and say, "Well, this work is criticizing terrorist violence, or this work is criticizing any other ideology we don't care for, and I can just sort of expose the critique and ride along behind it, and I've done some critical work as well."

I don't think that stance is always wrong. I think there are lots of comics that do perform that kind of critical work, and it's worth exploring it when they do.

What would be an example of a comic that does do that kind of critical work?

Well, you used V for Vendetta as an example, and I think you can actually make a great argument that that's a comic we can read both ways.

It is a comic that especially in its third book, that does end up criticizing basically the ideology of the first two books. I think that Moore and Lloyd grew up a lot in the hiatus when that series wasn't being published. And they end up unpacking and to some extent contradicting their own ideology. Not completely, but to some extent. So that would be a great example of a book where I think you could do critical readings that are reading the book with the grain, exposing critiques that it already makes, but you could also do equally valid critical readings that are reading it against the grain and pointing out all the ways that Moore and Lloyd are still invested in those ideas from earlier on in the book. And certainly with Moore of course this pattern of the way he writes female characters—that book definitely falls in with that.

So I don't want to say that you can never find a good critical reading in a comic, or a good critical reading in comics studies. You absolutely can. I just felt like there was also this other type of reading that we weren't doing. We weren't doing critical readings that were unflattering to the comics. And I just wanted to open up the argument and put that on the table.

How do you adjudicate that? What sort of evidence do you look for to say, well this is a critical reading, or this isn't?

I think you just have to look at it on a case by case basis, with each individual text as you look at it. For me, I was trained as a literary scholar, that's where my home is, and what I do for a living most days. And so for me I often start just doing a textual reading of the comics. And that's one of the things that I think comics criticism right now is pretty good at. Though I think it sometimes lets those readings play out only within certain predefined parameters. We've gotten very good at doing these formal close readings or textual close readings to show when the comic conforms to our values. But we don't always look at the ways in which a comic might run against our values or challenge them or question them.

But for me, it'll always start with a textual close reading. And then one of the things I wanted to do in this book with my own criticism was to try to start opening criticism up to more contextual or historical readings or other kinds of readings as well. Because I don't think those get practiced as frequently in comics studies.

One creator you try to contextualize is Chris Ware. Sometimes there are claims made for Chris Ware and alternative comics that they're doing something very original because they're not in the tradition of superhero comics or comics for kids. The claim is that they're taking on more supposedly realistic subject matter and that makes them groundbreaking in some ways. Why are you skeptical of that claim?

Well, I mean, sometimes they are original. Obviously Ware's work is groundbreaking in some ways, in terms of his visual layout and his formal design. The material format of a project like Building Stories is obviously doing all sorts of new and original work there. So it's not like I'd say that work is never creative or never groundbreaking. In particular if you look back a couple of generations, in particular at the revolution in alternative comics in the 1980s and early 1990s did produce a lot of work that the mainstream comics industry wasn't really getting into at the time.

The problem is, I think, now a couple decades later, we don't see people talking about other kinds of comics. We don't see people like Ware in the anthologies he edited promoting other kinds of comics work. That chapter on Ware started out because I was stunned by the incredibly narrow range of his anthologies, the McSweeney's issue and the Best American Comics volume. And it just seemed like there was a lot that was getting left out of that story. So I wouldn't want to claim that that mode of alternative comics is never original or never groundbreaking. It's just that after a couple of decades, it's hardened into a set of clichés that are restrictive as the one's those alternative artists were trying to break out of.

You also note that Ware often performs marginality. What do you mean by that, and what does he get out of it? And why is it something of a problem?

Well, this is a point that some other scholars like Daniel Worden have made, not just about Ware, but about that whole circle of alternative comics artists. Maybe that generation in particular, because I don't know that a lot of people currently working in alternative comics that do that in quite the same way. But the idea is that the pathway to literary validation or artistic validation is to show their own marginality. In other words, to show that they aren't just working for a mass audience.

I think the most ridiculous example that I can think of is the way that a lot of alt comics artists like Ware and Ivan Brunetti have created this version of Charles Schulz where Charles Schulz is always depressed. The "comics will break your heart" quote they like to circulate so often, where Schulz is seen as kind of this depressive outsider artist, and not as the guy who created one of the most popular comics franchises of the 20th century. They're overlooking the tremendous commercial popularity of his work in order to recast him as this culturally marginalized artist.

Or Ware himself—obviously he's being very self conscious and sarcastic when he does it, but every time he publishes one of those comics like, the "Ruin Your Life: Draw Comics" strip, it clearly—that ran in art exhibitions. He's had work shown at the Whitney Biennial.

So obviously this is an artist who has not been rejected by the art world, the way that he suggests comics always get rejected in his strips. So there is something knowing about it, but I also felt like there was something very self-aggrandizing about that stance. The idea that here is probably the most culturally legitimated comics artist, talking about how illegitimate the art form is in order to increase his own bid for literary respectability as some kind of neglected outsider.

It's also used to justify the fact that he doesn't seem to be much interested in the work of women artists, right?

Well certainly he wasn't in those two anthologies.

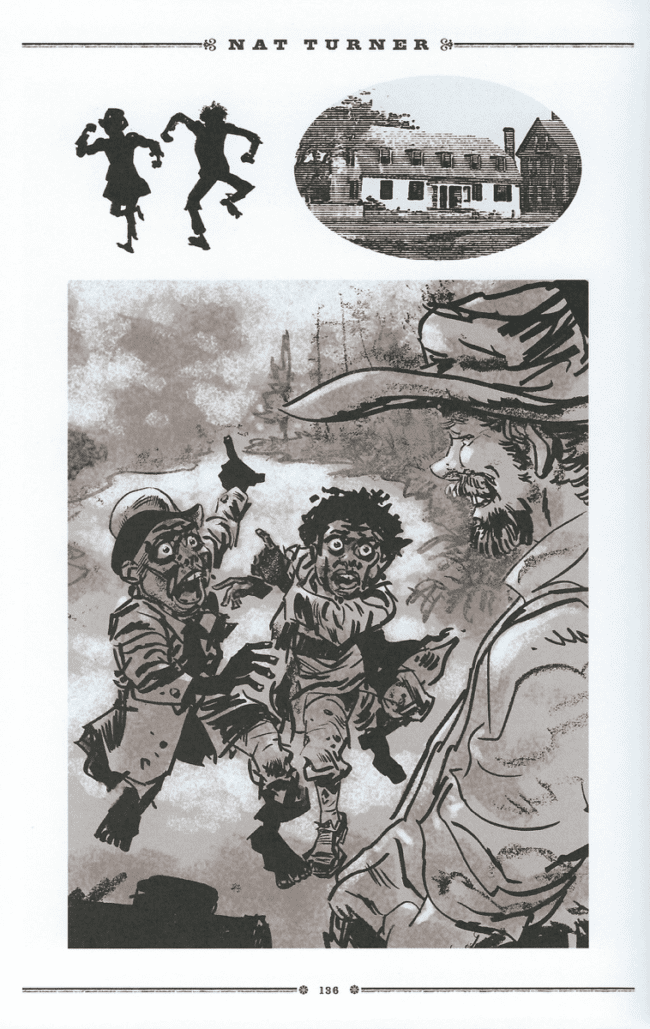

The comic that comes in for the harshest criticism in your book is I think Kyle Baker's Nat Turner. You call it "bullshit," which is a technical term from Harry G. Frankfurt. Could you explain what you mean by that? And do you think, in light of your criticism, that this is a book that people should be teaching?

I don't know that I'd recommend that other scholars not teach it. But if they do I would hope that they'd teach it with more of an awareness of all of the inventions and fabrications and falsehoods that Baker has put into that book, instead of just assuming or taking it for granted that it's historically accurate.

One of the things in that chapter that troubled me the most, and this is probably why that chapter is so much longer than any of the rest, is I kept finding scholars who were just taking it for granted that Nat Turner was historically accurate.

Jan Baetens and Hugo Frey talked about the authenticity of Baker's imagery. But when you look at the sources or antecedents of those images, they're anything but authentic. We have images of the houses that Turner's rebels raided, and they don't match the photos Baker was using.

He has all of these devices in Nat Turner that are very visually arresting, that are meant to make the book look like it's an artifact of the 19th century. But most of them aren't anywhere near historically proximate to 1831 and the Southampton rebellion. So I just kept seeing these little references to scholars basically taking other scholars' words for granted that the novel is historically accurate, and then you look back at those scholars, and you find out that they're just taking Baker's word for it, and Baker is just making it up as he goes along.

When I called Nat Turner "bullshit" I meant it in that sense very specifically defined by Harry Frankfurt, where he says that bullshit isn't the same thing as lies. Lies actually respect the authority of the truth. Which is why they try to conceal the fact that they're violating it. The bullshitter doesn't care whether something is true or false, they just sort of go with it. They are utterly indifferent to the truth as having any authority or value in describing the world, and I felt like that was where Nat Turner settled down.

But so many critics were willing to accept Baker's claims that he was telling a historically accurate story at face value that I really felt like I needed to go in and unpack that, and again start opening up a conversation we weren't previously having.

Part of the reason it's canonical is that there's a perceived dearth of canonical comics works by black creators, is that right?

Even more so than canonical is that there aren't a lot of works by black creators that have been continuously kept in print. There are black artists doing all sorts of interesting work across all sorts of different genres, but they tend to disappear from print pretty rapidly. So if you're deciding a syllabus then you might decide, as I did a few years ago, that Nat Turner is the best option. Because it's the one you can order for your students; it's the one they can actually buy in the bookstore. Whereas tracking down some of those earlier works aren't so easy when the publishers keep allowing them to lapse out of print.

You identify the way Nat Turner uses invidious racial stereotypes to represent black people. You point out minstrel stereotypes, for example

And again I wasn't seeing that reflected in the scholarship. Some scholars were even describing Nat Turner as a work of historiographic metafiction, which is a name for a particular type of postmodernist fictions which subverts historical narratives, undercuts historical stereotypes, renounces clichéd characters. And I just saw Nat Turner doing the opposite of all these things.

And I thought we needed to open up a conversation that didn't start from the assumption that the job of the critic is to justify the artist's work. But instead we could take the work as it comes to us and apply our scholarly abilities to it and see where they lead us, instead of assuming that the job of the critic or of the scholar is to ultimately endorse the work we're writing about.

To end on a positive note, what's one work of comics studies (other than your own!) that you think is really exceptional or worthwhile?

There are a ton of them. And I don't want to give the impression that this is being written as a slam book, or an attempt at smearing rivals or anything like that, because that isn't why I went into the project.

I couldn't have written the book if it weren't for lots of good work being done by other scholars in the field. It's just the nature of the project, since I'm trying to open new conversations and open new ways of talking about comics, I necessarily focus more on the places where I disagree with my colleagues, rather than places where I agree.

But as far as some of the really great works of comics scholarship out there, obviously the first that leaps to mind is Bart Beaty, whose work was tremendously useful to my own as I was working on this project. And in particular his book Comics Versus Art, which did a lot to shape the way I thought about comics and cultural legitimacy. In particular, how comics relate to cultural institutions, and how maybe our view of that hasn't kept up with their changing role in society.

Also his work on popular culture and European comics in the 1990s. It would have been impossible for me to write the chapter on Marjane Satrapi—I couldn't have done that without Bart's work to contextualize it within the world of small press French comics. So his work has been valuable to me.

A couple others out there who I think are doing great work: Brannon Costello's book on Howard Chaykin; that's a fantastic book. That actually has the conclusion I wish I'd written for my own Grant Morrison book. I think he did a great job of contextualizing Chaykin within the larger comics culture and the larger field of comics studies. Barbara Postema's work on comics and narrative theory has been great.

So there's tons of great critical work out there. But unfortunately it was the nature of this project that I wasn't writing about the work I find most valuable.