One of many sizable bummers about PictureBox Inc's 2014 closure was their star cartoonist CF's sudden loss of a publishing partner that shone a consistent, unlikely spotlight on his work. CF, aka Christopher Forgues, is one of those multi-disciplinary artists who it's always seemed like comics might lose to some other form's bigger pond - he's a formidable musician, a skilled printmaker, and an exhibitor of plastic arts. After PictureBox CF still made cool comics-related stuff: a large size magazine here, comics printed on receipt-paper rolls there, and a string of impressive shorts for the top rank of international anthologies. But consistent solo books were absent for years, a situation made all the more frustrating by a promised Fantagraphics release of the final volume in the modern-classic Powr Mastrs series's failure to materialize. CF's comics themselves aren't for everyone, a textbook study of far-out material best served by a publisher who understands the stuff they're printing and works to situate it in a context. PictureBox was a perfect match, and their disappearance led to more than half a decade of reduced visibility for their most influential artist.

This story has a happy ending though! Stepping into the breach last year came Anthology Editions, the weird book-publishing arm of music label Anthology Recordings, whose stated aim of "uncovering and fashioning cultural narratives as books" is sympatico with what PictureBox often attempted with their releases. The connection to a wider underground culture provided by having a record label as publisher is an obvious plus, and honestly Anthology is doing the work and putting together a pretty stellar backlist of comics-type books, with Brian Blomerth's Bicycle Day and the Crude Intentions anthology more than earning shelf space alongside CF. Whether his new home has re-energized him or we're just seeing a bunch of stacked-up work finally clearing a bottleneck on its way to release, there's been new CF books this year and last year, something that couldn't be said for almost a decade.

The books themselves are pretty great, and they showcase an artist who hasn't stood still in the years since his last one. CF's final PictureBox release, Mere, was easily his most unusual. A collection of short zines that "had to be done quickly," light on both narrative and the intricate showpiece delicacy of some of his previous work's finer moments, Mere's motivating purpose seemed to be harnessing as much energy as possible while sandblasting the comics form down to its simplest and most direct operating system. The comics for anthologies like Mould Map and Lagon that followed pulled back from this precipice, but given the expansive canvas of a full book once more, CF went back to chopping Mere's wood.

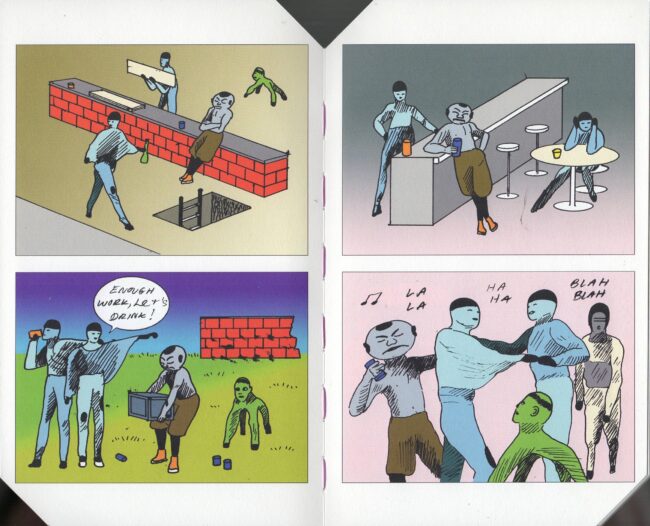

Pierrot Alterations, CF's first book with Anthology Editions, is an unapologetically avant-garde comic that only escapes being outright confrontational by virtue of its visual beauty. It's barely a story for the first half, not one at all for the second, but such is the visionary quality of what does leak onto the pages that one returns to it again and again, looking for missing pieces and secret links. Pierrot Alterations begins as the chronicle of a small group of semi-human (or mutant or deformed or maybe just cartooned) beings' efforts to build a city on top of a vast natural landscape. Though they seem sidetracked more often than productive, the project moves forward. As the harlequin-like twins Cygnus and Vega bog down in drink and squabble, the squat, marbleheaded Regulus seems to be developing and refining a set of supernatural powers.

The simple grace of CF's pencil drawings finds a handsome partner in this, the artist's deepest foray into computer coloring. The bright, contrasting hues and crude gradients he favors make the subtlety in his drafting even more subliminal, pushing readers from panel to panel without resorting to the considered sloppiness that much of Mere employed for the same purpose. The speedy clip this comic's two-panel pages read at is important, because the connective tissue between its individual frames is stretched so thin it's translucent. Rare indeed is the panel that refers directly to another one, rarer still the set piece or dialogue exchange. The closest CF gets to such is a quiet moment featuring Diphda and Ogma, two quadrupedal creatures who in every other scene silently watch their more humanoid companions' travails. Staring at a near-completed building in the middle of a field, one asks "Why do they want to be inside of that?" "It's a mystery to me," is the response.

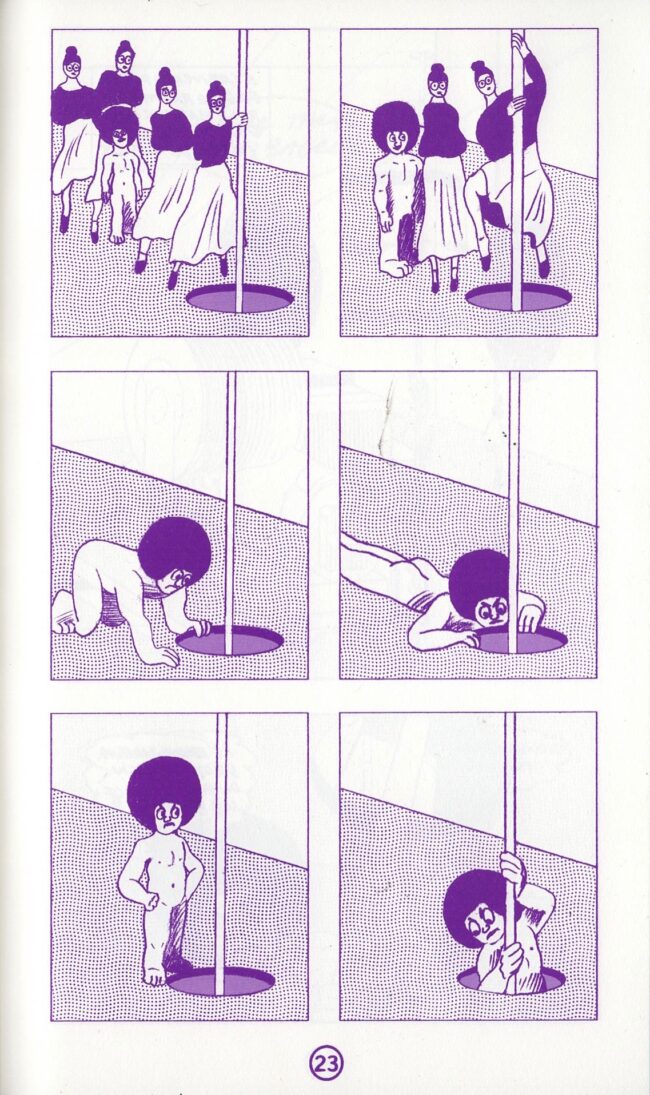

The building, it's worth pointing out, is rendered in CF's ultra-simple straightlined style as brick and windowpane, one pattern of rectangular boxes atop another. In this it resembles the gridded structure of the comics page as much as anything else, and it's easy to read these strange animals' perplexity at confinement as a more metafictional cry for liberation from boxed-in drawings. Their creator, who memorably dedicated Powr Mastrs to "the characters herein", seems inclined to listen. In the following scene the mage Regulus shows off a magic trick with two stages which address two different audiences. First - for Vega - he molts away his lumpy gray skin and becomes a bird, flying over the horizon and into the pure whiteness of a nearly empty page. Then - for us readers - he dives at a hole in the ground, disappearing into a space rendered first as a black oval, then as a circular die-cut hole in the book's paper itself. We follow, of course, by turning the punctured page in question, and the book erupts into its second half, a dizzying story-free procession of drawings.

Graphically, this segment of Pierrot Alterations most closely resembles CF's 2011 sketchbook/art book Sediment, which overwhelmed by grouping clusters of tiny figure drawings onto pages little bigger than a cigarette pack. But these larger pages are game time, not practice. In some images, careful readers will see show-through of drawings that appear not on the pages overleafing from the ones that show the pictures we can see they originally backed, but in another section entirely. What appears to be a random blast of wordless sketches to fill up the remainder of a book whose already feather-light story has ended is revealed as orchestrated composition, a sequence. CF's comics have long invited readers to contemplate the idea that the medium's construction of narrative is determined as much by the organization and proximity of pictorial elements as it is by things like continuity or language. The weird, structure-questioning creatures from earlier in the book flit through the backgrounds of some of these pages, providing a tenuous tether to the first half's story. Maybe the society being constructed there has now been built, and what we're paging bewilderedly through is an evocation of urban chaos? No answer is provided.

Regardless, it's a feast for the eyes. The speed and energy that CF's recent books prioritize has often come at the expense of the detail-rich spiderwebby, drippy post-Art Nouveau picture making that pops from the pages of Powr Mastrs and his other earlier comics. CF is one of only a few American cartoonists to have invented an immediately recognizable individual style of abstract drawing that's all his own - think Jack Kirby's signature "krackle", or Steve Ditko's windows into nightmare psychedelia. CF's looping, whorling, melting, strangely architectural assemblages of precision pencilwork splay across image after full-page image, with the grid of the day planner he drew them in providing strangely comforting undergirders. These are some of the most impressive drawings CF has published. The book concludes with, perhaps, a note of guidance for the flummoxed reader. A quote from the poet and translator Kit Schluter speaks of poetry as "a workaround to... specificity" which "upends the storied uselessness of the genre to which it refers and empower(s) it absolutely". Pierrot Alterations, then, is perhaps CF's attempt to do the usually fruitless labor of rendering comics as poetry, creating something that aims for that medium's unique impact rather than a mimickry of its form.

More comprehensible if no less enigmatic is CF's newly published second book with Anthology, William Softkey & the Purple Spider. This book is a return to the wheelhouse for its artist, the kind of bizarro science fiction-inflected narrative that first brought him to a wide audience's attention. Purple Spider is far from a Powr Mastrs redux, though: the lessons of Mere and Pierrot Alterations are in evidence on every page. With similarities to just about every book he's ever published, in a lot of ways this is CF's most representative comic, but it isn't playing to the cheap seats. The weirdness and visionary aspects of those older works are just as much in evidence here as any genre riff or stylistic flourish.

Purple Spider also bears notable similarities to the work of PictureBox's other star publishee, the cubist mangaka Yuichi Yokoyama. In a strong echo of Yokoyama's final PictureBox book, 2013's World Map Room, Purple Spider's plot focuses around intruders entering a powerful and paranoid guardian's personal library, and the disturbances that result. But where Yokoyama's characters almost never exist to do anything more than explicate his settings, here CF's bitch and moan refreshingly, and even stand a chance of moving something like a plot along. This comic also has a strong video-gamey feel to it, one previously more likely to come from comics by other members of CF's Providence, RI noise-comics cohort like Brian Chippendale and Mat Brinkman. Taking place mainly in a towering "gravityproof core that contains an elevator the size of a house",the book almost inevitably follows a gamelike leveled structure, and its use of different fruits as a booster for characters in danger recalls any number of similar devices in games from Pokemon to Mario.

William Softkey & the Purple Spider's titular character is himself slightly reminiscent of Nintendo's famous plumber, perhaps crossed with Leos Carax's silver-screen troll "Merde". "He is very poor, and naked..." goes the only intro we are given to our Afro'd dwarf protagonist, a pest control contractor by trade. William is called by Mr. Wish, owner of the compound that provides the book's setting, and ordered to remove a tiny, 5 million-pound purple spider that has breached his library's sanctity. Grumble in the finest working-class tradition though he may, it's clear this isn't an offer William can turn down, and a flying saucer soon conveys him to his destination. As otherworldly as this setup is, it also feels upsettingly workaday, with William fitting perfectly into the mold of the harried gig worker, summoned by cell phone to provide nonessential labor for a member of a higher class. "The point is I don't want to deal with this at the moment," says Mr. Wish, and off William goes like the legions of laborers we summon by pushing glowing buttons with CF'ian names - Uber, Postmates, Instacart, and the gold standard in dehumanization, Taskrabbit.

Part of what made Powr Mastrs so exhilarating was the Edenic freedom of its setting, "Known New China". Characters slept outside, walked around naked, and seemed tethered to no economic system but subsistence. Purple Spider's Mr. Wish is highly reminiscent of the Powr Mastrs character Mosfet Warlock, an accomplished necromancer whose thirst for knowledge regularly leads to disastrous consequences. But while Warlock's context as a character is limited to the world of CF's imagination, Mr. Wish is disturbingly reminiscent of a figure like Elon Musk, a feckless elite accustomed to total control whose understanding of the mysteries his subordinates plumb is perilously lacking. "He just wants to be around the research," says one of the Gigglewindow Sisters, whose experiments with gravity have reduced what was once a mansion to an elevator and sub-basements. Indeed, William is only contracted to remove the purple spider because Mr. Wish incorrectly assumes that he's illiterate.

All this subtext becomes text immediately after William enters Mr. Wish's library, where books and shelves background action out of Mad Max or Deathrace 2000, with intruders hunted down and annihilated by a sleek car propelled by a shadowy unseen figure. This is all rendered crisply and clearly, in a Kirbyesque 6-panel grid, for maximum smack. Here the speed-and-power lessons from Mere float close to the surface: it's as impactful an action set piece as CF has ever done.

Still, like most effective sci-fi, Purple Spider is more visionary parable than straight metaphor, with more pages devoted to CF's wild imaginings than his ruminations on social caste. Intricate vehicles and machines are drawn in styles alternately painstaking and doodled, but never less than striking. The character designs are as outre as any CF has come up with, but they all squash and stretch convincingly enough to really move. Two screen tone patterns - a wavery dot matrix and a field of regularly spaced diagonal lines - serve the same purpose the bright colors in Pierrot Alterations do, providing depth and dimension to the drawings without sacrificing any of the reading experience's speed. The imagery finds an ideal balance between scrawl and elegance, imagined with enough depth to make its physicality believable, rendered casually enough to make things feel vague and dreamy.

William finds the spider eventually, and his attempt to smash it leads to another pyrotechnic visual crescendo. In a seriously fucked, formally audacious closing sequence likely to leave readers crosseyed, a gravity warp leads to the book's characters becoming "alloys" of one another, with CF's patented rigid psychedelic forms rampaging over panel borders and the gutters between pages. The Gigglewindow Sisters and the library itself become a single computer chip, scooped up greedily by the powerful, knowledge-hungry being made up of the fused Mr. Wish and Purple Spider. They begin a journey across an endless desert, unperturbed by their new condition. It's tempting to see this as another point made about our world, something about how even revolutions always leave rulers and servants as a basic condition of existence - but that also feels like a bit of a stretch. Either way, William has become one with Wish's flying saucer, floating smiling above it all.

The influence of CF's Powr Mastrs-era work was so deep and pervasive on a wave of alternative comics makers who have since flowered into publication and fame that it's tough to imagine he'll ever again be as notorious a figure as he was in the late 2000s and early '10s. Those old comics are as important a signpost of their era in the medium as anything else published at the time. Combine that with the lessened visibility CF's had since, and this still relatively young cartoonist can feel like an elder statesman, someone who has made a mark, had an influence, and become a part of comics history. All that may be true - but in his most memorable message to the generation of pencil-wielding cartoonists who followed in his footsteps, CF expressed clear disappointment at seeing all the comics that looked like his. "Follow your own star!" he exhorted. He's walked the walk since. The return to wide release and book-length comics that Anthology Editions has provided shows an artist now many steps ahead of the segment of his journey that had such importance to so many. Still following his star, CF is creating work right now that's as vital and accomplished as anything in his bibliography. It's a consummate pleasure to have one of our great cartoonists back on the shelves.