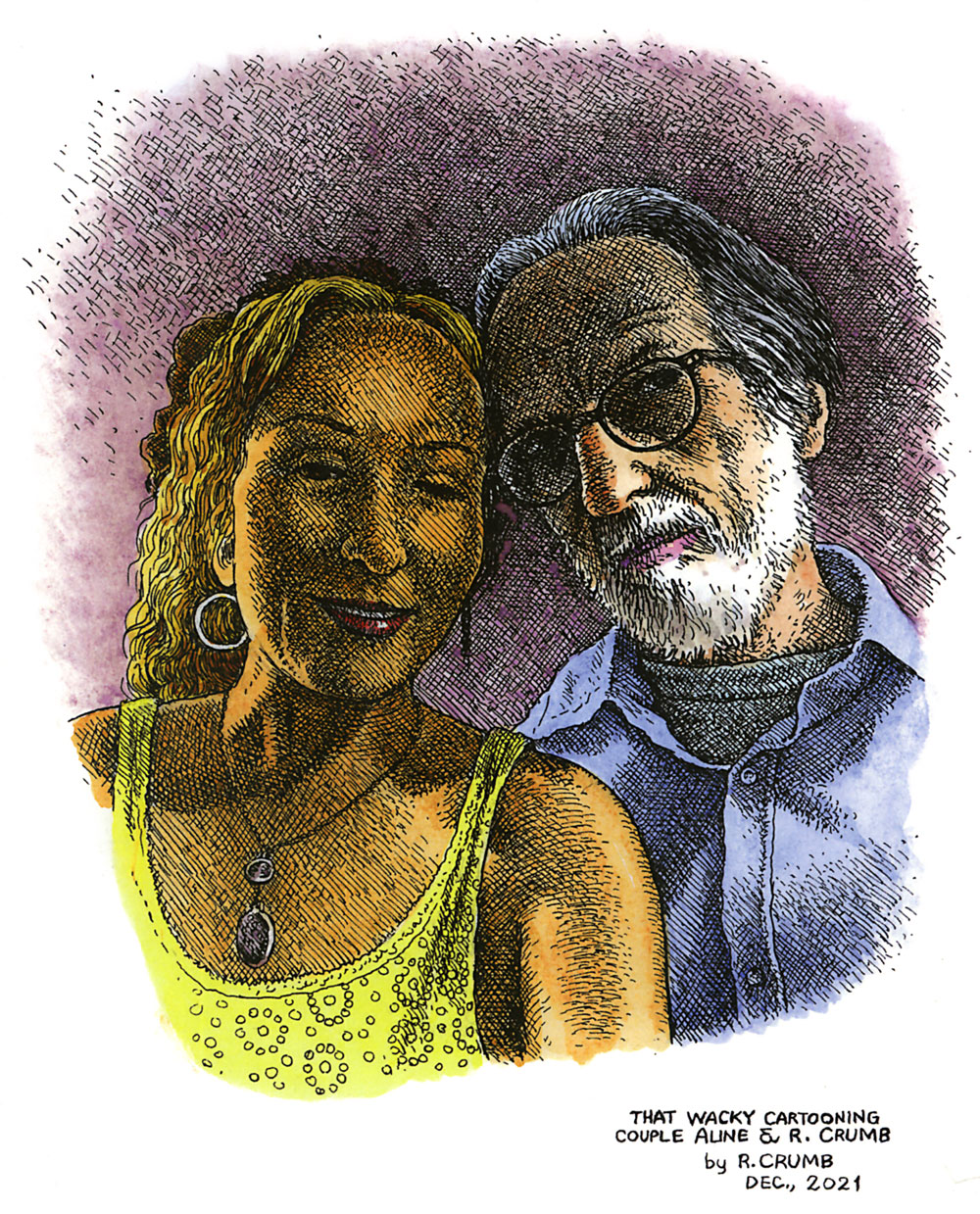

Legendary underground cartoonist Aline Kominsky-Crumb, whose self-deprecating and wickedly funny autobiographical comics often focused on the lives of herself and her husband, Robert Crumb, died on November 29th at their home in France from pancreatic cancer. She was 74.

"We're very saddened that Aline Kominsky-Crumb, cartoonist, mother and Robert's wife for almost 50 years, has passed away at 74 years old," wrote Peter Poplaski and Rika Deryckere, artist friends of the Crumb family, in an email announcing the news. "Aline previously beat her bout with colon cancer–changed her diet, stopped drinking and transformed her body with her intense yoga workouts–but quickly succumbed to pancreatic cancer in the last several months of this year. Because her father died from pancreatic cancer at an early age, Aline always feared it would claim her too, and her fears were ultimately justified.

"She was the hub of the wheel within her family and community. She had huge amounts of energy which she poured into her artwork, her daughter, her grandchildren and the meals which brought everyone together. It was her energy that transformed the American Crumb family into a Southern French one, with her daughter Sophie, living, marrying and having three French children there. She will be dearly missed within that family, and from the international cartooning community, but, especially by Robert, who shared almost the last 50 years of his life with her."

Writing for Artforum, comics historian Dan Nadel summed up the importance of her work:

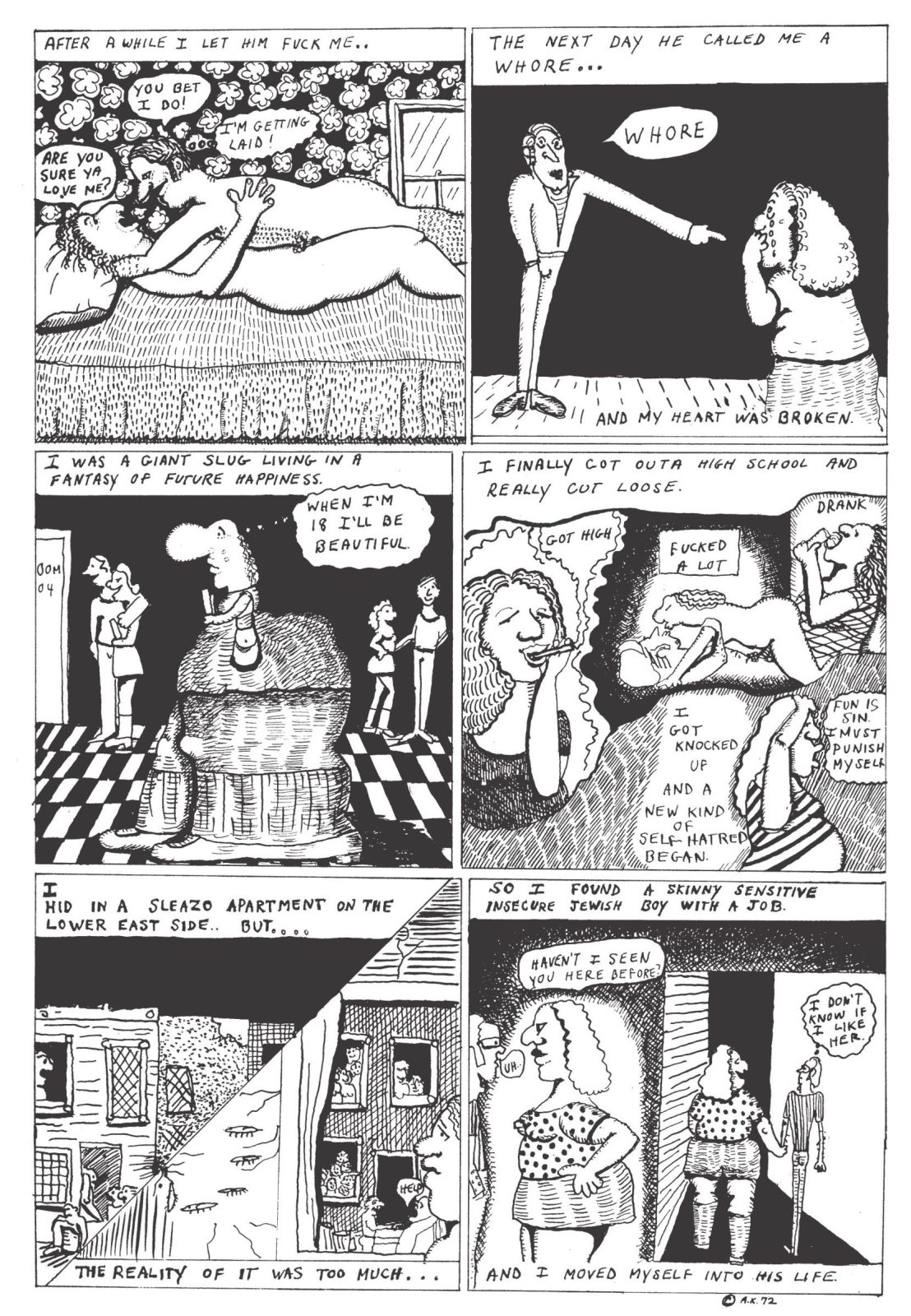

"Aline's legacy in comics can’t be overstated: She was the first artist to make comics relentlessly examining the private physical and emotional lives of women. Her quavering, thin lines were as intentionally imperfect as the lives she depicted. And that was the point: Aline refused to cover up or gloss over—everything was in service to her subjects, which include, but are hardly limited to: negative self-image, sexual neurosis, lust, marriage, children, travel, grandchildren, and the daily pain and pleasure of simply being in a body."

Kominsky-Crumb was a key figure in the underground comix/s movement and a founding member of the all-women's title, Wimmen's Comix, before launching her own women's collection, Twisted Sisters, along with co-editor Diane Noomin. Noomin died of uterine cancer on September 1, 2022. The loss of two of the most influential female artists of the underground period within a span of just a few months seems particularly cruel. News of her death–and subsequent sad reactions–soon spread on social social media, with many fans and friends weighing in on the loss.

"The passing of Aline Kominsky is so very sad. She was great. Great at being alive," wrote cartoonist Gary Panter on his Facebook page.

"The loss of Aline Kominsky-Crumb hit me pretty hard yesterday. I spent a year writing about her and the rest of the Twisted Sisters while I was in college, and that first wave of underground comix was so influential in my decision to become a cartoonist," cartoonist Jen Sorensen wrote on Facebook. "I feel a deep connection to those autobio comics from the '70s and '80s. Aline's work was soulful and witty and I'm sorry I never got a chance to meet her. Between her and Diane Noomin and the passing of Leslie Sternbergh a few years ago, it does feel like the end of an era."

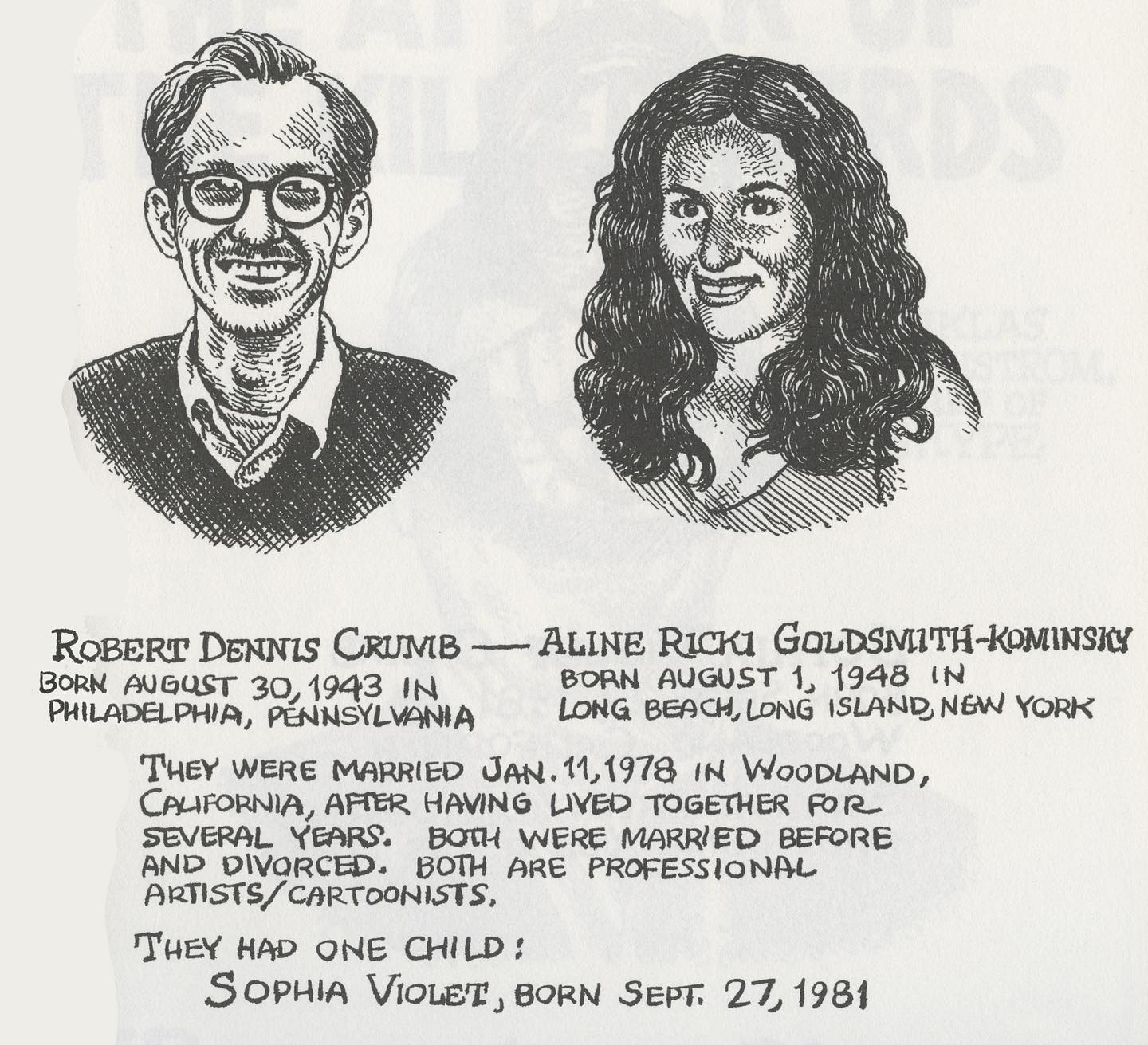

Aline Kominsky (née Aline Ricky Goldsmith) was born on August 1, 1948, and grew up on Long Island, NY. She had early artistic ambitions, but her parents "didn't try to encourage it."

"I had every lesson available to children, but only to make me into a refined product so that I would marry some rich Jewish dentist and get a house in Great Neck," she told cartoonist Peter Bagge in a 1990 interview with The Comics Journal. "Except when I was 8, I really wanted to paint and they let me take painting lessons. This real sincere, idealistic Pratt student turned me on to painting, real painting. I actually did some oil paintings that were good. From around age 8 to 14 I was real creative and serious about painting and ceramics and pastels. Then I got into boys and totally gave it up."

Kominsky-Crumb was known for a fully confessional style of storytelling, with a number of her strips focusing on her troubled childhood and strained relationship with her parents, particularly her mother.

"My mother was spoiled and used to living high—her parents had a lot of money—and my father was irresponsible," she told Bagge. "They were really young; they got married when they were 19 or something. My mother was 19 when she had me, and my father was 23. They were real immature, reckless and crazy. Horrible psychotics to grow up with."

After graduating from Lawrence High School in Long Island's Five Towns section, she briefly moved upstate to attend the State University of New York at New Paltz, where, as she told Bagge, "I got pregnant the first week. I ran away a few months later. I climbed out the dorm window... I made it for one quarter. I made it to Thanksgiving vacation."

She lived for a time on Manhattan's Lower East Side, enrolled in Cooper Union where she studied art, and married Carl Kominsky. The couple relocated to Tucson, Arizona, and she enrolled in the University of Arizona, graduating with a BFA in 1971. After her first marriage ended, she kept the name "Kominsky" because, she told Bagge, "I liked it better. Kominsky’s more ethnic-sounding."

While in Tucson, she was introduced to the cartoonists Kim Deitch and Spain Rodriguez. She began reading underground comics, some of which inspired her to try her hand at the form.

"I started buying them," she told Bagge. "I saw Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary by Justin Green. That was a comic that really moved me to draw. When I saw what he had done with this autobiographical, straightforward, crazy story about everything that happened to him, I started approaching it in this straight-forward way and it was really satisfying to me. I had this revelation. I thought, 'I could do that. That's what I should do.' The light bulb went off."

With encouragement from Deitch and Rodriguez, she decided to move to San Francisco to join its thriving UG comix community.

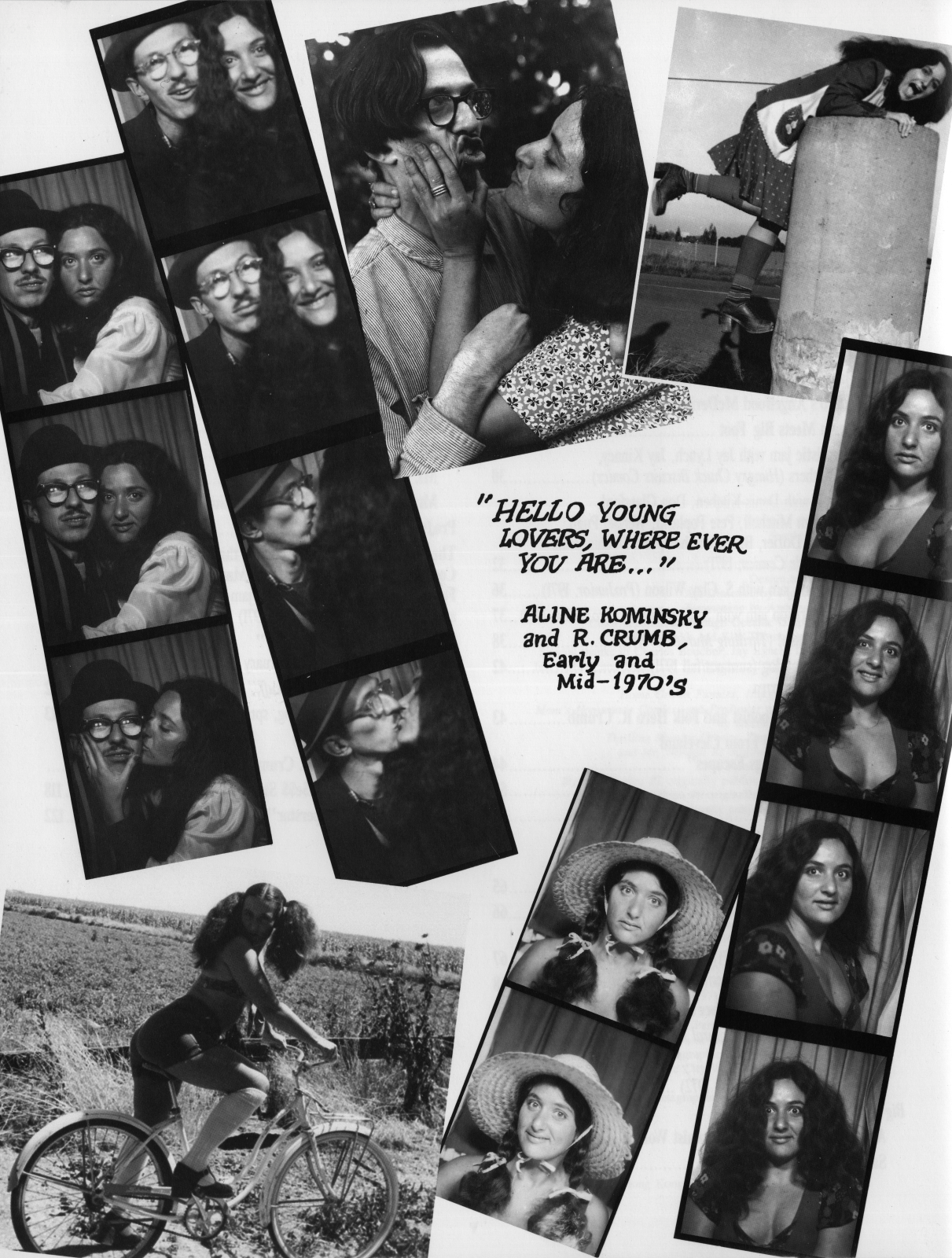

"It was a pretty tight scene," she told Bagge. "Then I went to the Wimmen's Comix meetings where I ended up meeting Trina [Robbins] and Sharon Rudahl (I think), and Pat Moodian and Larry Todd, who was going out with her. Then I met Dan O'Neill and all the Air Pirates. I went out with a lot of different guys... I went out with Gary Hallgren and Willie Murphy, Dan O'Neill, Kim Deitch, Spain. Everybody. Too many... I won't tell you about the more despicable ones. I was a wild 23-year-old. But when I met Robert [Crumb], it was true love."

Though she later left the Wimmen's Comix collective due to issues with its direction, and launched her own women's title, Twisted Sisters Comics with Diane Noomin, Kominsky-Crumb was a founding member of the group and the experience was important in her development as an artist.

"For me personally, I just wanted to get my own work published," she told Bagge. "I wasn't very skilled, and this was a beginning group of artists. I didn't care if it was men or women. They accepted me. I felt like nobody was skilled so I didn't feel stupid. I certainly wasn't going to get in Zap Comix. For me, it was less intimidating that it was women. I guess Trina had experienced exclusion from the men, so she felt very strongly about creating a separate vehicle for women. I hadn't experienced that. The men I knew were real nice to me, like Dan O'Neill, Willy Murphy, and the Air Pirates. They were very encouraging and supportive."

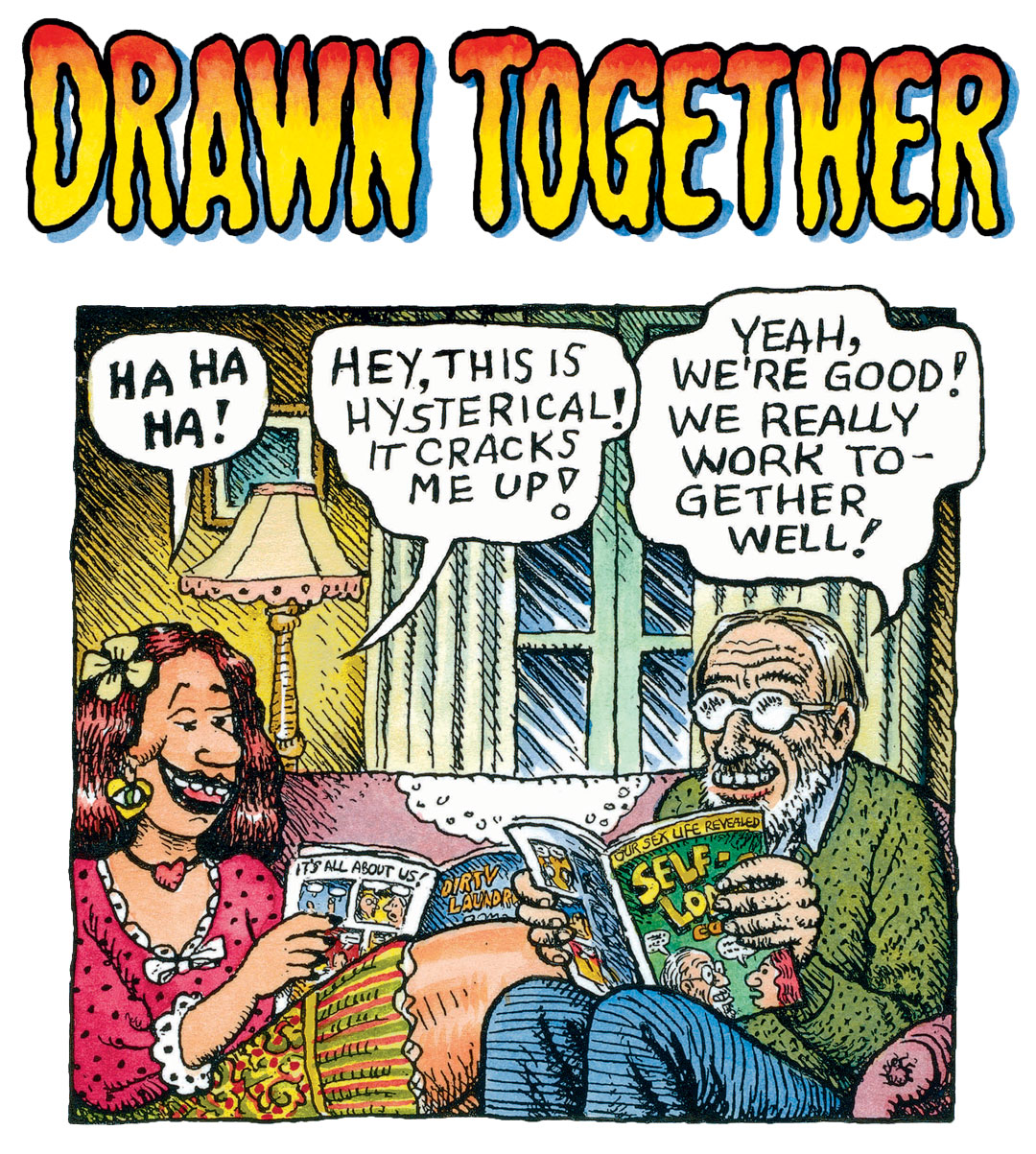

Soon after she began her nearly 50-year relationship with Robert Crumb, the pair began collaborating on comic stories, with each drawing themselves as a character in the strips. The work appeared in various publications over the years, including issues of Dirty Laundry Comics (collected by Last Gasp in 1992) and Weirdo, the sprawling anthology series started by Robert in 1981. Kominsky-Crumb would later edit 9 of the last 10 issues of Weirdo, which ended its run as a periodical in 1990 shortly after the couple moved to France; she co-edited a final giant-sized issue in 1993.

Her loose drawing style, uninhibited content and personal connection to the world's most famous underground artist inspired some to derisively refer to Kominsky-Crumb as the "Yoko Ono of Comics". At times, she herself also jokingly used that appellation. Such criticism, especially when it came from rabid fans of her husband's work, could serve as a motivation.

"It was stimulating to me and shocking [all] at once," she told Bagge in 1990. "I got off on it. Feedback is artistically inspiring. I never expected too much adoration for my work because it's so uncivilized... I liked the idea of being obnoxious and bratty that way because [Robert's] fans are so repulsively fixated on him. I kind of enjoyed being a slut-brat, an irritant. I generated great hate mail.... To me, art was part of a continuing need to express myself from the time I was a kid. It was just this compulsive need that I think always existed in my life."

Many others praised her writing, and felt that her drawing style perfectly fit her material. Chief among her supporters, she told Bagge, was her husband.

"[Robert] just said, 'Your work is really funny and unique. You should just do that.' He always thought it was really funny and made it on some level. He said, 'I don't know why it's this good, but it is.' That was really an important thing to me.... He was really an amazingly giving, loving, affectionate person. I was always deprived of that kind of attention before... Bill Griffith and Art Spiegelman also liked my work a lot, and they were real supportive to me."

Writing in the New Yorker, Art Director Françoise Mouly observed that Kominsky-Crumb "revelled in portraying herself in unvarnished words or crude drawings that made the reader feel one was peeking inside a diary, not a published work."

An early attempt at a comprehensive anthology of Kominsky-Crumb's work came in 1990, when Fantagraphics published Love That Bunch. That same year, the editors of The Comics Journal, Gary Groth & Helena Harvilicz, wrote in issue #139 of that magazine:

"In some respects, Aline Kominsky-Crumb epitomizes the underground spirit. You want cruddy-looking, scrawled drawings? You want painfully honest self-revelations? Well, by God, from her very first strip onward (1972's "Goldie, a Neurotic Woman"), Aline's got it all. And while her art has gained in maturity and complexity since then, it has never renounced its essential cruddiness - or its scathing honesty.

"This approach has proven to be a bit of a double-edged sword. Aline's work enrages her many detractors partly because its rough surface is so effective at masking her wit, skill, and intelligence. If you let down your guard, it's easy to confuse Aline the artist with her often buffoonish and overbearing cartoon alter-ego 'The Bunch'. Aline dares people to think the worst of her - and because her execution appears so guileless, they often do. Small wonder even her most avid fans often admit that their initial reaction to her work was one of revulsion. But the fact remains: any cartoonist who has ever sat down and deliberately scrawled out an artfully ugly drawing, who has dared to be stingingly, nakedly candid in an autobiographical story, owes her a tremendous debt."

When asked if she ever felt slighted by the attention paid to her more famous husband, she told Bagge in 1990, "How could I? He's produced such an amazing body of work, he's accomplished so much, that I'd never expect to get the same kind of treatment that he receives. I'll admit that when I see an article on underground cartoonists or women cartoonists and I'm not even mentioned, I'll feel slighted.... Basically the amount of attention I've received so far is enough to make me happy. I have no major complaints in that regard. Also, I think my work is great and I'll eventually be recognized as the genius that I am!"

Others agreed. In recent years, her work has received the attention of the established art world. In 2007, an exhibition of her work was held at the Adam Baumgold Gallery in Manhattan. In 2020, LA's Kayne Griffin held a solo exhibition of her work. "Kominsky-Crumb’s work is as urgent, open, and expressive in content as it is in style," the gallery stated in its exhibition materials. "Influenced by German artists Otto Dix and George Grosz, Kominsky-Crumb draws with a rough and imperfect hand, depicting distorted, loose, and sometimes grotesque figures imbued with raw, irreverent, in-your-face vigor. As Roberta Smith writes [in the New York Times, reviewing the Adam Baumbolg exhibition], '[Kominsky-Crumb] excels at the drawn-and-written confessional comic. … Her clenched, emphatic style echoes German Expressionist woodblock in its powerful contrasts of black and white, and her female faces … have a sometimes uncontainable fierceness.' Kominsky-Crumb was ahead of her time in juxtaposing the contradictory nature of female sexuality with a proud, complicated feminism. Through her exaggerated alter-ego, Bunch, Kominsky-Crumb unapologetically and truthfully depicts her world - the good, the bad, and the ugly."

In 2007, M Q Publications released Kominsky-Crumb's Need More Love, a graphic memoir which included comics, writing and other examples of her art. In 2018, an hardcover reissue of her collected comics, Love That Bunch, was published by Drawn & Quarterly. This edition expanded on the book initially released by Fantagraphics.

"I was privileged to publish Love That Bunch, Aline's comics collected into book form for the first time, in 1990," said Fantagraphics Publisher Gary Groth on the company's Facebook page. "This was at a time when Aline barely registered on anyone's radar as a cartoonist, and one reason to publish the book was to show the world that, yes, she stood, apart from her husband, as an independent cartoonist of the first rank. However, I think I felt even more privileged to know her personally for these last 35 years; she was genuine, honest, uninhibited, and, as you might imagine, incredibly funny."

One of Kominsky-Crumb's final interviews was with Sarah Moroz of Artforum this past February. "I have stayed out of the mainstream my entire life, partially because the work itself determines that it’s not mainstream work," she remarked. "We started our comics off in the revolutionary underground. I was a painter with a degree in fine art, and I chose to do stuff that could be read on a toilet. Now, my work is taught at Harvard and women have written PhDs on my work, which really amazes me. So it's full circle, if you hang in long enough. And I guess if your work is meaningful, eventually it's recognized by the establishment. On one hand, you can be a contrarian and say 'no' to everything. That's understandable, too. But on the other hand, if you say "yes," more people will read your work, and that's why you do it: to communicate. I had so many young women come up to me in 2018 on my book tour, and that was the most touching thing. They said, 'I was dealing with this too, and when I could laugh about it, everything was much lighter.'

"It made me feel connected."

In addition to her husband, Kominsky-Crumb is survived by their daughter, Sophie Crumb, who is a cartoonist living in France, and three grandchildren. A private ceremony was held by the family and close friends in France on December 5th. All were encouraged to spend the time between 11:00 and 11:15 AM CET in a collective meditation.

"Light a candle - think of a memory altogether with her love," the invitation read.

* * *

A second look of the life of Aline Kominsky-Crumb, featuring tributes from friends, family and admirers, can be found here.