Among the achievements for which Alex Raymond is noted in histories of this oft-abused artform is that he drew three nationally syndicated comic strips simultaneously. Jungle Jim and Flash Gordon, both of which began January 7, 1934, and Secret Agent X-9, which began two weeks later on January 22. Given the high quality of the illustrative evidence available, Raymond’s achievement seems all the more remarkable. To do such good work on three comic strips at the same time attests, we are tempted to say, to Raymond’s towering graphic genius.

Before surrendering to the temptation, however, we might take a moment to reflect, and in that moment, remember that Secret Agent X-9 was a daily only comic strip and Jungle Jim and Flash Gordon appeared only on Sundays. Moreover, Jungle Jim was the “topper” for Flash Gordon—a one- or two-tier strip that filled out a single page, with Flash occupying the bottom two-thirds. The two Sunday-only strips made up a single page of the funnies, just as Bringing Up Father and Snookums or Blondie and Colonel Potterby and the Duchess did. Raymond may have drawn better (more illustratively, in greater detail), but he did no more strips in an average week than George McManus did with Jiggs and Maggie or Chic Young with Blondie and Dagwood. Six daily strips and one Sunday page.

Raymond has enjoyed an unremitting and entirely deserved chorus of acclaim, but, according to most versions of his life and career, it is his skill as an illustrator that entitles him to this idolatry, not the quantity of his work. Moreover, Raymond earned a secure place in the history of the medium solely as an illustrator of other men’s stories. As such, he was not, strictly speaking, a cartoonist: a cartoonist (by definition—mine anyway) both draws and writes his material, and all of the great strips with which Raymond’s name is associated were reportedly written by others. Even Raymond’s post-war undertaking, Rip Kirby, was supposedly written by others, chiefly Raymond’s editors at King Features in concert with Raymond. Or so the story goes; we’ll take another look later on.

Raymond’s celebrated art is the focus of a new book from Hermes Press— Alex Raymond: An Artistic Journey—Adventure, Intrigue, and Romance by Ron Goulart; Introduction by Daniel Herman (242 19 x 13-inch pages, b/w and some color; hardcover, $75). This is an art book of the very first order. The pictures are all reproduced from original art—Flash Gordon and Jungle Jim (both January 7, 1934-April 30, 1944), Secret Agent X-9 (January 22, 1935-November 16, 1935), and the later Rip Kirby (March 4, 1946- September 29, 1956), all of Raymond’s masterpieces of illustrative art. Organized chronologically, a third of the book is devoted to Flash; another third to a miscellanea—X-9, Jungle Jim, and book and magazine illustration; the remaining third, to Rip Kirby.

The generous sampling of the strips also appears in chronological order within each section, but a lot of strips are missing: this is, after all, not a reprint volume of the totality of any of the titles. Each strip is meticulously dated. Some pages reproduce at enlarged dimension (perhaps original art size) individual panels from a strip on the facing page—“details,” in curator lingo—which better reveal the intricacies of Raymond’s artwork.

A few strips are reproduced in color from their newspaper appearances, but the book is fundamentally a black-and-white showcase.

A few strips are reproduced in color from their newspaper appearances, but the book is fundamentally a black-and-white showcase.

Despite the gigantic page measurement, the strip reproduction is small. Sunday Flash measures 7.5x11 inches at most, usually smaller; and the daily Rip Kirby is 2.5x8 inches, about the size it appeared when initially published.

Goulart’s text traces Raymond’s career and, for each of the strip titles, offers summaries of a few of the stories and a brief critique of the artist’s developing drawing style. As usual, Goulart is a font of information about ghosts and assistants. He errs only a couple of times. Fred Waring, the popular bandleader and radio-tv personality of the 1920s through the 1950s, was not ever president of the National Cartoonists Society; he was, however, an enthusiastic fan of cartooning and hosted a summer weekend for NCS at his resort in Pennsylvania. And in describing the exploits of Secret Agent X-9, Goulart says Raymond didn’t draw about a month of “The Mask” story; but it’s the later “Iron Claw” story that was ghosted by a somewhat inferior artist.

But Goulart is always a good read and a fund of information. Here, he adds to the Raymond canon, noting, for instance, the several Big Little Book incarnations of Flash Gordon. But for the full career rundown and biography, you need Tom Roberts’ 2007 superior 20-years-in-the-making production, Alex Raymond: His Life and Art, the hands-down best book on Raymond and his art (312 9 x 12-inch landscape pages, b/w and color; $49.95).

Roberts is a book designer and an illustrator himself, and his book is an elegant example of the book designer’s art and crammed with beautiful illustrations by the artist Roberts’ so avidly admires, taken from Raymond’s pace-setting comic strips plus book and magazine illustration and Christmas cards and pin-ups—a lavish compilation that includes much seldom (if ever) seen art, glowing on slick paper in full color whenever the original was in color.

Not only does Roberts cover Raymond’s early career assisting on Tim Tyler’s Luck and Blondie, but he examines Raymond’s lesser known achievements as a documentarian in the Marines during World War II and as an illustrator of fiction and advertising in the 1930s and 1940s.

For the biographical text, Roberts interviewed members of the Raymond family (four of the artist’s five children and two of his brothers) and surviving friends and assistants (chiefly Ray Burns, who assisted on Rip Kirby) and twenty-two Marine Corps veterans. The result is the only thoroughly complete biography of the famed cartoonist.

Alexander Gillespie Raymond, Jr. was born October 2, 1909, in New Rochelle, New York, the first of the seven children of Alexander Gillespie Raymond, a civil engineer, and Beatrice Wallaz Crossley. Young Raymond attended Iona Preparatory School in New Rochelle on an athletic scholarship, but his plans for higher education were curtailed due to his father’s death in 1922. By 1928, money from the estate had run out, and at eighteen, Raymond went to work in order to help support the family, taking a position as an order clerk in the Wall Street brokerage firm of Chisholm and Chapman.

When he lost this position in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, he was encouraged to exploit his talent for drawing by his neighbor, Russ Westover, the creator of the comic strip Tille the Toiler. For two months, Raymond was able to take night classes at the Grand Central School of Art, working days as a solicitor for the James Boyd Mortgage firm. On New Year’s Eve as 1930 turned into 1931, Raymond married Helen Frances Williams; they had five children.

Subsequently, in May 1931, he briefly assisted Westover, who soon secured additional work for him in the art department of King Features syndicate, where the youth came to the attention of Chic Young; soon Raymond was assisting on Young’s Blondie. In late 1931, Raymond began assisting Young’s brother Lyman on Tim Tyler’s Luck.

Cast initially in the mold of Bobby Thatcher and others of that ilk, Tim Tyler's Luck had started August 13, 1928, as an aviation strip with a kid hero. In 1932, Young took his cast to Africa, and the strip became a kind of jungle strip. At first, Young drew the strip in a cartoony style, but as the stories became more realistic, he hired assistants to render the adventures in a more realistic, illustrative manner.

“From May 1932, Raymond worked consistently with Lyman Young,” Roberts reports, “and on and off for Chic Young. Hardly a week would pass that Raymond didn’t work on either (or both) the daily or the Sunday Tim Tyler’s Luck.” Raymond did all the figure drawing in the daily and Sunday Tyler for most of 1933, drawing realistically in a confident outline style with virtually no shading or cross-hatching; it was thoroughly competent but undistinguished linework.

Tyler, like all Sunday comic strips, was accompanied by a topper, a short shrift strip with other characters that ran at the top of the page carrying the main feature, and Raymond did Tyler’s topper, Kid Sister. Raymond had stopped working on Blondie just after Dagwood and the eponymous flapper married on February 17, 1933. (Raymond drew many of the people at the wedding.) By this time, he knew he wanted to pursue a career in cartooning; the King Features bull pen would be his launching pad.

In late 1933, King Features officials began looking for features to compete with two popular Sunday comic strips offered by rival syndicates—Buck Rogers, space adventures in a science fiction future, and Tarzan. In one of those fated celestial quirks, both of these strips had debuted on the same date, January 7, 1929.

Raymond submitted samples for the sf adventure, making two false starts —as detailed for the first time I know of by Roberts—before being awarded a Sunday page with Flash Gordon on the bottom two-thirds. He was then instructed to concoct a jungle strip as the page’s topper. This was Jungle Jim, which owed more to white hunter Frank Buck and animal trainer Clyde Beatty than to Burroughs.

At the same time, Raymond entered the syndicate's competition to find an artist for a new crime-fighting daily strip, which, in order to compete with the soaring popularity of Chester Gould's Dick Tracy and Norman Marsh’s Dan Dunn—Secret Operative 48, would be written by the celebrated master of hard-boiled detective fiction, Dashiell Hammett. Raymond was picked to do this strip, too, and thus he began 1934 as the illustrator of three comic strips, a virtually unprecedented circumstance.

The only disappointing aspect of Goulart’s art book is, oddly, in the very reproduction of the artworks the volume exists to showcase. In all of Raymond’s syndicated work, he resorted to a fine line for feathering and many details; a fine line typically outlined faces and other forms. Unhappily, many of the fine lines disappear or are broken rather than continuous in some of the reproductions.

I suspect that the original art was shot “in color” instead of black-and-white, a practice increasingly followed in books reproducing original art (ever since my Children of the Yellow kid tome in 1998, whose editor, Richard V. West, inaugurated the practice). This tactic undeniably produces the art as accurately as is possible: blue lines indicating Ben Day and pencil lines not quite completely erased show up with this treatment—just as they do on a museum wall. An unintended consequence, however, is that sometimes the black lines are brownish rather than black. And the “color” of the paper on which the drawings are made also shows up. Brown lines against yellow-ish paper lose some of their clarity and thereby fall short of the museum-wall effect.

This unhappy situation in an art book with this one’s ambition is unfortunate, but the book itself, while suffering somewhat, is scarcely devastated. Many more of the strips are accurately reproduced than are flawed in their fine lines. And the maneuver of reproducing some panels as enlarged “details” compensates for the shortfall in some of the strips. Any fan of Alex Raymond’s oeuvre should have this handsome volume in his library.

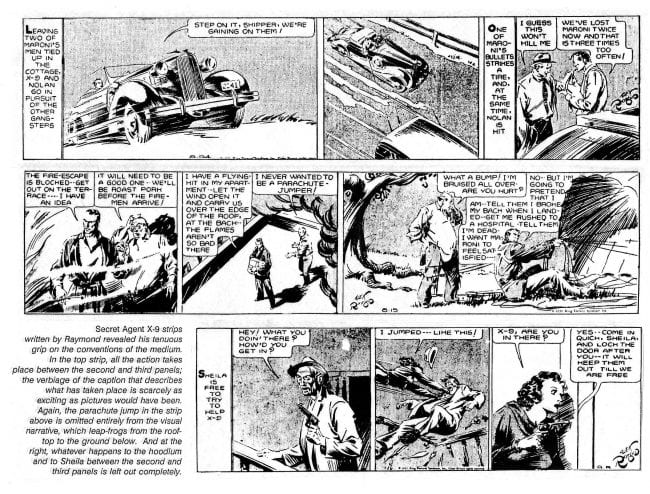

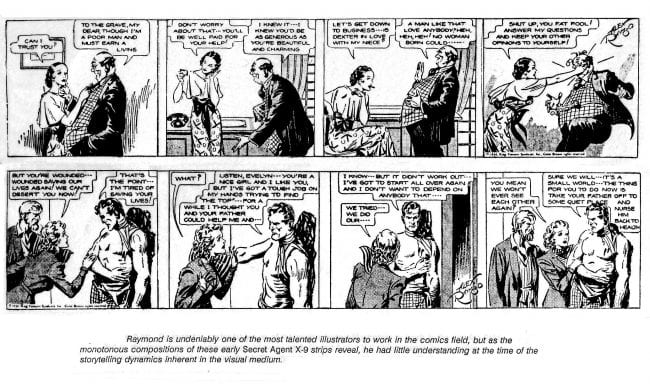

Even though Raymond’s consumate artistry elevated the strips above the mundane, they were not all of equal excellence. Flash Gordon is unquestionably Raymond’s masterpiece. His great skill in executing the other strips magnified his impact upon the profession, but neither of the other two of his initial trio of strips was particularly distinguished as a comic strip. Secret Agent X-9 was written, for most of Raymond’s stint on it, by Hammett, whose understanding of the comic strip medium was not particularly acute. When Hammett quit, Raymond reportedly wrote it himself for a brief time, then another mystery writer, Leslie Charteris, took over. Neither Raymond nor Charteris proved very good at writing a comic strip.

As I’ve said elsewhere (in a book of mine, The Art of the Funnies), despite Raymond’s great talent as an illustrator, his deployment of the comic strip medium was undistinguished. The plots of the two X-9 adventures presumed to have been written by Raymond stumble along with motiveless actions, and narrative breakdown leap-frogs from one event to another, continuity gaps filled in with huge chunks of prose narration. Both these adventures rush to conclusion, much of the action taking place “off stage” so that it must be narrated to us in captions, weakening the drama of events.

The strips often lack the variety of panel composition—such things as varying camera angles and distances—that would lend visual drama to the story. Compared, say, to Milton Caniff’s work on Terry and the Pirates a short time later, much of Raymond’s X-9 seems a monotonous parade of panels in which the characters appear always the same size, always seen from the same angle. Moreover, Raymond’s people never change expression: X-9's grim albeit handsome visage seems carved in stone, and his facial expression is repeated on the head of every handsome male character in the strip. And Raymond’s representation of his hero grates a little: his X-9 is a bit too dapper, more of a fashion model than a street fighter.

Raymond’s women, although superbly drawn and seductively beautiful, all look alike, and when he makes both young women in a story dark-haired, we can’t tell one from the other—with much resulting confusion about the story’s plot (particularly after Hammett had left). Raymond fared much better on the Sunday pages. The mode of storytelling there—by weekly installment—lends itself to his illustrator’s skills without revealing his failings as a comic strip storyteller. And on the Sunday page, Raymond had more room in which to exercise his graphic skills.

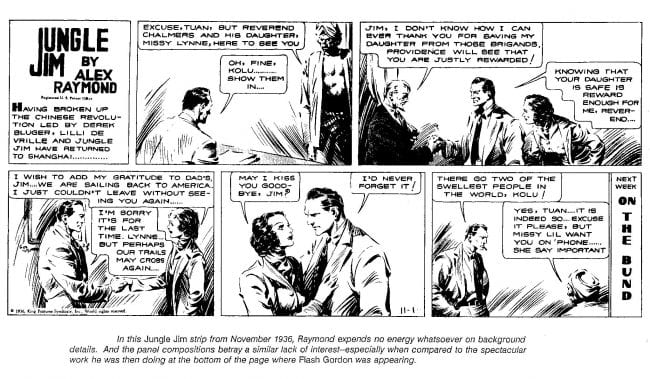

But it was more than format that fired Raymond’s imagination. Jungle Jim alone, although well-drawn, would not have secured Raymond a place in the pantheon of cartooning’s greatest practitioners. The strip followed the exploits of a hunter named Jim Bradley as he righted wrongs in the jungles of southeast Asia.

But Raymond’s heart was clearly not in this work: after a couple of years, his pictures appear almost dashed-off. For weeks in mid-1936, the strip’s panels were almost wholly devoid of background detail. The strip consisted entirely of pictures of Jim and the other characters talking.  They are all attractively drawn. Raymond’s technical virtuosity was so great that his figure-drawing alone rescues the strip visually. But he was obviously not putting much work into the feature. His effort—his creative energy, his imagination and skill and dedication—was being poured into the feature at the bottom two-thirds of the Sunday page, Flash Gordon.

They are all attractively drawn. Raymond’s technical virtuosity was so great that his figure-drawing alone rescues the strip visually. But he was obviously not putting much work into the feature. His effort—his creative energy, his imagination and skill and dedication—was being poured into the feature at the bottom two-thirds of the Sunday page, Flash Gordon.

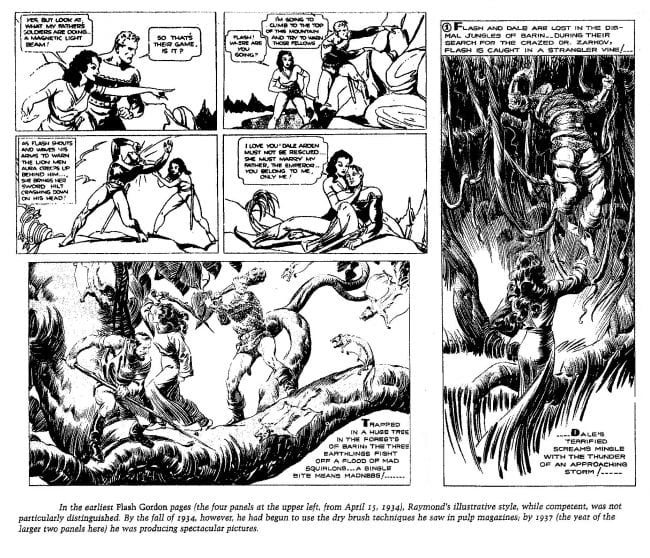

The graphic excellence that would distinguish Flash Gordon did not spring, full-blown, from Raymond’s pen with the strip’s debut. At first, he drew in the same unembellished linear illustrative style he had used when ghosting Tim Tyler’s Luck for Lyman Young in 1933. But before long, he began to feel the influence of other styles of illustration, and the artwork in Flash started to change.

In using the work of other artists as models for changing his style, Raymond was scarcely unique. Most artists are influenced by what their colleagues do, and they borrow freely this technique and that. When the borrowing is well done, however, it goes beyond mere imitation and gives to the borrower’s work a new dimension wholly his own. His work becomes an amalgam of all he has borrowed, unified by a single creative consciousness into something uniquely his—his own style.

It is not clear who influenced Raymond’s emerging style the most, although there are several candidates, and he probably borrowed a little from them all (and from others we don’t know about). In rendering the futuristic architecture of Mongo, Raymond was obviously imitating Franklin Booth, a turn-of-the-century artist of the futuristic. And Goulart notes that Raymond’s contemporaries, Matt Clark and John LaGatta, also supplied models that he employed. “From Clark’s slick illustrations,” Goulart wrote, “Raymond borrowed a good deal, including the prototype for the new improved version of his other hero, Jungle Jim.” The influence of LaGatta, who painted beautiful women elegantly gowned in ways that revealed rather than concealed their figures, can be seen clearly in Raymond’s increasingly sexy renderings of Dale Arden and the other women in the strip, all of whom started wearing exotic clinging garments.

By May 1934, Raymond was feathering his linework and modeling figures more extensively, and he began brushing shading into the landscape of Mongo, giving the scenery texture as well as topography. And by the end of the year, Raymond’s drawings showed the influence of the dry brush technique of pulp magazine illustrators: his brush strokes were orchestrations of tiny parallel lines, suggesting thereby the stroke of a brush nearly dry of ink. Although Raymond sometimes let his brush go dry, he normally kept enough ink on the implement to give his drawings a liquid sheen.  The appearance of dry-brushing, however, gave his pictures great depth and textural beauty, and he employed the same techniques in Jungle Jim and Secret Agent X-9.

The appearance of dry-brushing, however, gave his pictures great depth and textural beauty, and he employed the same techniques in Jungle Jim and Secret Agent X-9.

In the summer of 1934, Raymond began to vary the layout of the Flash page. The strip had been designed in a four-tier format—four stacked rows of panels. As Raymond’s imagination became more and more engaged with the feature, this format seemed increasingly restrictive. In July, he started using an occasional two-tier panel—a picture that spanned vertically the space of two tiers on the four-tier grid—in order to capture more dramatically the atmosphere in which his hero lived. A Booth-like city in the sky is pictured in one such large panel, the increased vertical space giving the scene a dramatic impact it would not have had in a single-tier panel.

Seeing the results, Raymond quickly abandoned the four-tier layout in favor of a three-tier arrangement that gave him room to develop all his pictures more extensively. With the larger panels, his backgrounds grew more lavish, and the strip’s locale acquired an authentic ambiance. And in these spacious surroundings, the heroic posturing of his characters lent the entire enterprise a majestic air. The world of Flash Gordon was becoming manifestly real.

By 1936, the strip was being drawn on a two-tier grid, every panel at least twice as large as the panels had been when Flash began. Raymond had given up Secret Agent X-9 in late 1935, focusing entirely on his weekly page of comics. But it was Flash not Jungle Jim that absorbed his creative energy. The pictures in Flash were luxurient with telling atmosphere; in Jungle Jim, as I’ve noted, they were scarcely furnished at all. By 1937, the drawings in Flash were heavily modeled, the figures given weight and shape by an intricate pattern of brush strokes, the backgrounds enhanced by an extravagant latticework of shading. And still Raymond continued to develop as a artist.

Having reached a level of stylistic achievement unequaled elsewhere in the Sunday funnies except in Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant (which began February 13, 1937), Raymond went on to evolve yet another impressive style in rendering Flash Gordon. By the end of 1938, the dry brush-like modeling and shading was giving way to a less sketchy manner. Raymond’s lines became thinner, more continuous and graceful; his pictures were defined more by linework and less by shading. They became exquisite tableaux, delicately rendered in copious detail. In this period—from 1939 until 1944 when Raymond joined the marines for the rest of World War II—Raymond’s work closely resembled Foster’s in Prince Valiant; it was the only time the work of these two great illustrators looked much alike.

Early in 1938, Raymond, perhaps following Foster’s lead, had begun to eschew speech balloons in Flash, but he floated his characters’ remarks in clusters of verbiage near their heads; a year later, he began burying speech within quotation marks in the caption blocks at the bottom of each panel. By this time, his storytelling technique was established. He simply illustrated bits of narrative prose, in one superbly rendered panel after another. But the beautiful pictures were sequentially related only insofar as they depicted successive moments in the narrative captions. Flash Gordon had become mostly an illustrated novel—not, exactly, a comic strip.

I don’t mean by this to belittle Raymond’s achievements—only to pinpoint them, to give him his due for what he actually did. And he did plenty.

That Flash Gordon, Dale Arden, Ming the Merciless and all the rest have become a part of the American cultural heritage is, in itself, a testament to Raymond’s accomplishment as well as to the power of the medium. Like Sherlock Holmes before him and James Bond afterwards, Flash Gordon leapt from the printed page into the hearts and minds of his readers and eventually emerged on the motion picture screen. But even before his celluloid incarnation in the 1936 serial, Flash was already as real to his readers as it is possible for a literary creation to be. And that was due almost entirely to Raymond, whose consumate artistry stamped the strip, the characters, and the stories with an illusion of reality that was more than convincing: it was spectacular.

Although Raymond is no longer credited with single-handedly producing Flash, it is nonetheless undeniable that it was his graphics that clothed Don Moore’s stories in their most irresistible raiment. As Stephen Becker has observed in his Comic Art in America (1959): “What made Flash Gordon outstanding was not the story; along the unmarked trails of intersteller space any continuity was original. Nor were Flash and his lady friend radical departures from the traditional hero and heroine. But Flash was beautifully drawn.”

Moore’s contribution, however, has been exaggerated. In his Raymond biography, Tom Roberts takes up the puzzle of how much writing Raymond did on his strips. Although Moore has long been credited with “writing” Flash and, Roberts says, Jungle Jim, King Features has nothing in its files that illuminates the issue, so Roberts resorted to published articles and other sources, making a good case for his contention that Moore’s “writing” was much less than scripting the strips.

What Moore did, in Roberts’ judgement, was draft scripts from Raymond’s plot outlines, scripts that Raymond then refined, tinkering with the wording and other aspects of the narrative to suit his own sensibility. With access to the Raymond family archives, Roberts was able to examine what little evidence survives: papers that “show examples of Raymond writing and altering dialog for the Flash Gordon Sunday page.”

Moreover, since Moore didn’t start working with Raymond until mid- or late-1936, Raymond presumably wrote and scripted the strip for its first two-and-a-half years.

In any case, the stories are not notably inspired. Built archetypally around Flash as god-like redeemer (the savior from another world), the stories were suspenseful, fast-paced, and ingenious. But for all their ingenuity of incident, they were too fast moving to allow much time for character development. Flash, the polo player turned savior, is everything we expect in an adventurer—courageous, honest, nobly motivated, and above all resourceful. But he is nothing more. Apart from possessing the traditional, culturally-prescribed traits of a hero, Flash has no personality. His love for Dale is perfunctory: he is the hero; she, the heroine, and the customary relationship between such persons is love. In Dale’s pettish flashes of jealousy (which spark with such routine predictability throughout the run of Flash), we see all the individuality that she is allowed.

Said Coulton Waugh in his venerable The Comics (1947): “These lithe, sexy young people have an empty look—one feels that a cross-section would show little inside their hearts and heads.” But with Raymond’s drawing, we seldom notice this shortcoming. His graphics give the strip’s characters such life-like appearance that we overlook the absence of individual personality in them. They are larger than life—or, at least, more beautiful, handsomer, more graceful. And the beauty of these visuals seduces us into believing in the characters, who look and move like we would like to look and move.

“The total effect,” Becker said, “—slick, imaginative drawing with literate narrative—was one of melodrama on a high level, which should not obscure the fact that Raymond’s villains were throughly wicked or that his female characters were generally sexy. Flash rapidly became the premier space strip. It was wittier and moved faster than Buck Rogers; it was prettier and less boyish than William Ritt’s and Clarence Gray’s Brick Bradford.”

There is no question that it was Raymond’s art that brought Flash Gordon alive, his art that made the characters live in the minds of their readers. But that art could not flourish, could not reach the luxuriance of its full growth, in the small daily panels of Secret Agent X-9. Despite the considerable merit of Raymond’s work on X-9, neither the format nor the subject was amenable to the levitating magic that his art performed in Flash. And while the format of Jungle Jim was ample enough, the subject did not fire Raymond’s imagination as did the mythology of the redeemer in the tales of Flash Gordon on the planet Mongo. Flash Gordon is a clear instance of subject and artist locked in symbiotic embrace, the artist driven to achieve at ever higher levels by his subject, the subject elevated in turn by the artist’s endeavors.

Foster and Raymond produced impressive works. But for all their undeniable skill as illustrators, neither Foster nor Raymond (at this stage of his career) were cartoonists. The works that brought them fame and earned them their niches in the history of the medium are more akin to illustrated narratives, not comic strips. Word and picture did not blend in Prince Valiant or Flash Gordon in that uniquely reciprocating way that I insist defines a comic strip. Foster and Raymond were successful illustrators—spectacularly so on the pages of the Sunday funnies.

Still, the physical relationship of pictures to words in Flash Gordon and Prince Valiant is the same as in the venerable single-panel gag cartoon, and the words undoubtedly amplify the narrative import of the picture under which they appear, and vice versa. The words don't explain the pictures as they do in a gag cartoon: they are not the key to a puzzle that the picture represents as captions are to the picture in a good gag cartoon. The relationship between pictures and words in Flash Gordon or Prince Valiant seems tangential rather than integral. In most instances of these works, the narrative, the story, is carried almost entirely in the text. We can understand the story without considering the pictures.

Well, yes, but—but the pictures in Flash Gordon undeniably create the palpable ambiance of the story; they give it sweep and grandeur. And without the heroic elegance of its pictures, Flash Gordon is a shallow, sentimental saga. Many children's books are not substantially different in appearance from Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon: every page with its brief allotment of text carries an amplifying illustration. Still, Foster and Raymond did a little more for their narratives with their pictures than the average children's book illustration does for its narrative. The pictures supply visual information that fleshes out the narrative text. And the text gives nuance to the pictures. The words and the pictures may not blend, precisely, to create a meaning neither conveys alone without the other (as I’ve demonstrated they do in comic strips), but their interrelationship is intimate and complementary. Within the category of pictorial narrative, Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon are therefore closer to being comics than they are to being illustrated children's books. (For more in this tedious vein, consult my comment on June 15, 2016, at the end of my “Outcault, Goddard, the Comics” Hare Tonic piece, where the whole matter of definitions is explored tirelessly.)

With his next creation, however, Raymond became indisputably a fully-fledged cartoonist.

Raymond enlisted in the Marines on February 15, 1944, commissioned a captain in the Corps’ public relations arm. His last Flash Gordon appeared May 7; Jungle Jim, May 21. For six months in Philadelphia, he kept asking for combat duty and finally got it: he was assigned to the USS Gilbert Islands, an aircraft carrier in the Pacific, where, from April 1945 until the winding down of the War in the fall, he served as Public Information Officer, charged with observing and documenting the life of a Marine squadron. Raymond took photographs, drew and painted pictures and designed posters, all intended to help present the Marine Corps in a positive light to the world beyond the Corps. He saw action from aboard ship in the South Pacific at Okinawa, Balikpapan, and Borneo. He was released from active duty on January 6, 1946, with the permanent rank of major.

Raymond expected to return to Flash Gordon and Jungle Jim, but when he inquired about his imminent return, he was officially advised, by letter, that he was expecting the impossible. Since he had left his comic strips voluntarily to enlist, King Features was not obliged to hire him back to do either strip (which would have displaced Austin Briggs, who was then doing them both). According to Raymond relatives whom Roberts interviewed, Raymond carried for the rest of his life a bitter resentment about being “cast off with so little regard.”

But King wasn’t about to let one of its stars go into eclipse: they asked him to create a new strip, offering him a huge signing bonus, and when Raymond signed, it was with the stipulation that he would own the new strip and receive 60 percent of the profits, not the usual fifty. Taking a suggestion by Ward Greene, the syndicate’s general manager, Raymond developed a daily-only strip about a detective.

A Marine officer returning to civilian life, the title character Rip Kirby (who was, for a time, named Rip O’Rourke) was a startling departure among comic strip heroes: though dashing and debonair, he was an unabashed intellectual (he even wore spectacles), moved in the best circles of society, employed a British man servant, and had a beautiful girlfriend who was a professional model.  The girlfriend, a statuesque blonde named Honey Dorian (who, in preliminary sketches, was called Taffy), was a figment of the artist’s imagination, as almost all unbelievably beautiful women are, but Rip and his valet Desmond were modeled by Marines Raymond had served with.

The girlfriend, a statuesque blonde named Honey Dorian (who, in preliminary sketches, was called Taffy), was a figment of the artist’s imagination, as almost all unbelievably beautiful women are, but Rip and his valet Desmond were modeled by Marines Raymond had served with.

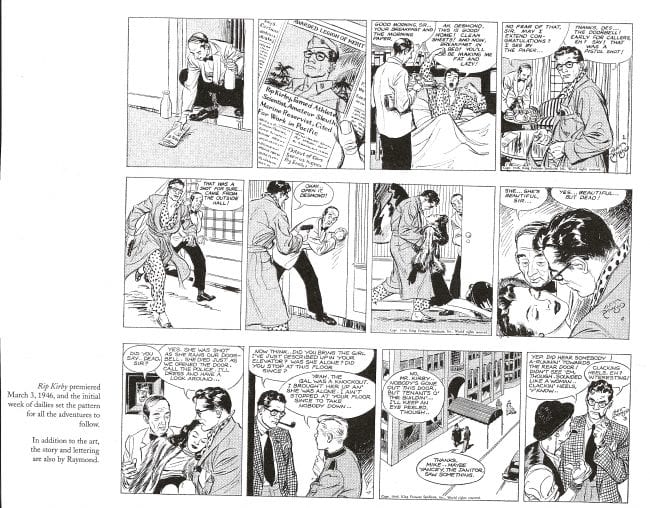

Beginning March 4, 1946, Rip Kirby started with a bang—a gunshot. In the four panels of the first day’s strip, we learn that Kirby has a valet who is as much devoted friend as servant and that Kirby is an “athlete, scientist, amateur sleuth” and a decorated Marine reservist. Then Raymond hangs us over a cliff in the last panel when Kirby hears a pistol shot.

The rest of the opening week is as expertly done as the first day, a tour de force of serial suspense, every day ending with a provoking panel, and each strip telling us a little more about Kirby. By the sixth day, we’ve got Honey Dorian to look at, and Raymond puts her long legs on ample display while also revealing that his hero is a musician and likes to sit at his piano (a grand piano) and noodle around on the ivories.

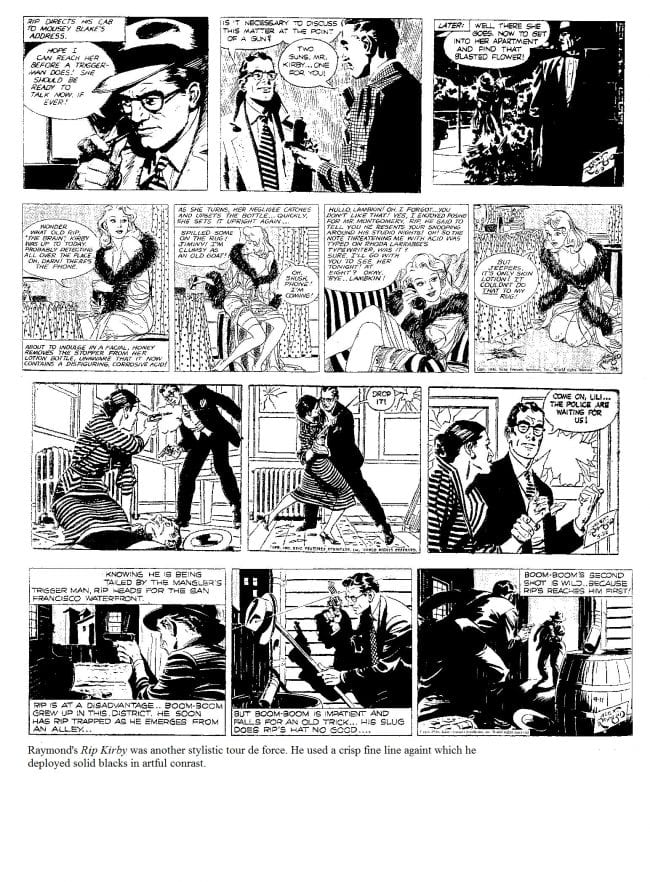

Rip Kirby is an advance in light years over Secret Agent X-9. In narrative breakdown particularly but also in the variety of his panel compositions, Raymond shows skill and expertise in managing the storytelling resources of visual serial continuity, blending words and pictures for both narrative and dramatic effect. Raymond, here and hereafter, is a cartoonist par excellence.

Once again, however, Raymond worked with others in writing the strip. Here, Roberts says, there is no doubt: the strip was concocted by Raymond in weekly story conferences with King’s general manager, Ward Greene.

Greene was more than a bureaucratic journalist. He had been writing novels in his off hours since 1929. He would eventually produce ten of them, including Death in the Deep South, a 1936 murder mystery that was the basis for the movie “They Won’t Forget” with Claude Rains and Lana Turner, Cora Potts (“Cabin Girl, Town Girl, Wife and Wanton” saith the cover of the paperback), and Ride the Nightmare (“about a highly paid, lusty, drunkard comic strip artist” saith the Web), reissued as The Life and Loves of a Modern Mister Bluebeard. Greene also wrote The Lady and the Tramp, a 1953 novel that was adapted by Disney for an animated movie with the same name.

Sylvan Byck, King’s comics editor, was also part of the writing team. After the weekly confabulation, Raymond probably did the actual scripting and dialoging of the strip.

For Rip Kirby, which, as a daily, would never appear in color, Raymond developed yet another distinctive illustrative style, deploying solid blacks dramatically in contrast to crisp fine-line penwork, giving the strip an appearance that set it apart from his earlier work. Observes Roberts: “Not having the benefit of [Sunday] color, Raymond nevertheless [colored] through his use of varying linework ... [creating] color through contrast, though the use of black, white and gray areas.”  Rip Kirby is at last receiving the attention it deserves. IDW’s Library of American Comics has produced several volumes of Rip Kirby, The First Modern Detective. The reprinting is up to 1964 through the seventh volume, the first four of which include all of Raymond’s stint on the strip; thereafter, John Prentice, a superb draftsman nearly Raymond’s equal, began, with the release of October 1, 1956, to imitate Raymond’s manner with astonishing exactitude. He continued the strip until his death in May 1999; Frank Bolles wrapped it up, ending the strip June 26, 1999. (The IDW books are 300-plus 10x11-inch pages, landscape, b/w with some color; hardcover, $49.99.)

Rip Kirby is at last receiving the attention it deserves. IDW’s Library of American Comics has produced several volumes of Rip Kirby, The First Modern Detective. The reprinting is up to 1964 through the seventh volume, the first four of which include all of Raymond’s stint on the strip; thereafter, John Prentice, a superb draftsman nearly Raymond’s equal, began, with the release of October 1, 1956, to imitate Raymond’s manner with astonishing exactitude. He continued the strip until his death in May 1999; Frank Bolles wrapped it up, ending the strip June 26, 1999. (The IDW books are 300-plus 10x11-inch pages, landscape, b/w with some color; hardcover, $49.99.)

Raymond’s Rip Kirby strip has never, to my knowledge, been reprinted with anything like the quality control its drawings demand. Pacific Comics Club published a series of thin but large-page Rip Kirby booklets in the 1980s but was forced to use proofs from somewhere overseas, requiring that the speech balloons be relettered in English; that was done clumsily, blemishing the appearance of the strips. And the reproduction of the artwork, although of high caliber, failed to capture Raymond’s distinctive fine-line rendering.

IDW has come closer, much closer: this is probably the best we’ll ever see Rip Kirby reproduced. Still, as series editor and designer Dean Mullaney notes, the quality of the King Features syndicate proofs varies, and the variance shows. Fortunately, it doesn’t show all the time everywhere: many strips are as pristine in this book as they were when Raymond turned them in. The books are exquisite productions—decorative flashes of color in the introductory pages, stunning jacket design, panoramic endpapers, and even a stitched-in bookmark ribbon (this last, an IDW signature).

Luckily for us all, the strip’s opening week—one of the best in comics history—as well as much of the first adventure are reproduced with gratifying accuracy in Volume 1. But about halfway through the first sequence, we begin to get occasionally muddy, blotchy reproduction. Happily, the stories are mature and suspenseful enough to hold our interest until the quality of the reproduction resumes.

Raymond began experimenting with rendering techniques before the end of the strip’s first year. In November 1946, he was using a brush to draw, not a pen, which had imparted to the first months of the strip its distinctive crisp aura. He was back with a pen by the fall of 1948, but within the next six months (which will be published in Volume 2 of the series), Raymond was deploying a brush again, giving his art a liquid line very much in the mode of Leonard Starr in On Stage. Eventually, Raymond would abandon the brush for all but shadows and wrinkles in clothing, and by the fall of 1950, he was drawing almost the way he drew at the beginning.

In practice, he drew with a pen—outlining faces, figures, background details; then he embellished with a brush, slathering in fat black strokes for wrinkles, shadows on accouterments, and so forth. That, however, isn’t apparent until Volume 2, which will carry the continuity into 1951. In Volume 2, we’ll watch Rip get discombobulated when his paramour, toothsome model Honey Dorian, is pursued by a handsome young chap with marriage on his mind. By the end of this adventure, we know, but Rip doesn’t, just how Honey stands in respect to him and his casual attentions. The tale unravels at the guy’s plantation in the South, a place called Blackwater. Could be in South Carolina; sinister associations.

Rip Kiby achieved rapid success, and Raymond developed a memorable series of secondary characters, usually criminally inclined—the toothsome Pagan Lee, competition for Honey; and the disfigured Mangler, Rip’s nemesis; and Joe Seven, Fingers Moray, Lady Lillyput among others. Roberts feels that Raymond’s work in Rip Kirby “inspired all the soap opera style strips of the fifties and sixties,” from Rex Morgan to The Heart of Juliet Jones, On Stage, Apartment 3-G, and Ben Casey—“all,” Roberts says, “are stepchildren of Rip Kirby. Every one of these can trace its origins to the success of Raymond’s strip.”

Raymond worked no longer on Rip Kirby, ten years, than he did on Flash Gordon, and he might have advanced the art of daily strip cartooning even more had he not died, tragically, while driving fellow cartoonist Stan Drake (Juliet Jones) in the latter’s new sports car, a Corvette convertible, on September 6, 1956. For the gruesome details of Raymond’s “last day,” consult Roberts’ book.

Raymond’s last published Rip Kirby, September 29, ends eerily with the con man villain of the story telling his mark that he has “bad news.”

Raymond’s place in the history of his profession is established and secured by his brilliance as an illustrator. The technical triumph he achieved in the three strips he launched in 1934 helped establish the illustrative mode as the best way of visualizing a serious adventure story. His work and Foster's created the visual standard by which all such comic strips would henceforth be measured.

And here we’ll stop, with Alex Raymond performing a tour de force of comic strip cartooning on his last comic strip.