The world’s longest cartooning career (79 years), as identified by the Guiness Book of World Records, came to an end Monday, April 10, with the passing of Mad artist Al Jaffee at the ripe age of 102. Death was attributed to multiple organ failure. He will always be known for the Mad Fold-In, which doomed the back page of every issue to parallel creases as readers collapsed words and image to reveal a satirical gag hidden in plain sight. He will also be remembered every time someone asks a stupid question about the painfully obvious and is answered with sarcastic comebacks. From its first appearance in issue #86 in 1964, the Fold-In was virtually never absent from the magazine while it continued to print new material. Only three issues of the hundreds that followed #86 did not have a back cover by Jaffee. “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions” made its debut in the magazine in 1965 in issue #98, and soon branched into eight paperback collections of original Snappy Answer gags by Jaffee. And anyone who grew up with Mad magazine will chuckle at the thought of his step-by-step guides to elaborately contrived inventions to solve the pettiest of everyday suburban American problems.

What’s less known is his un-suburban, trauma-filled childhood: the virtual abduction from his American home, and the familial poverty, disease, religious oppression and chaos that forged the armor of Jaffee’s unshakeable sense of humor.

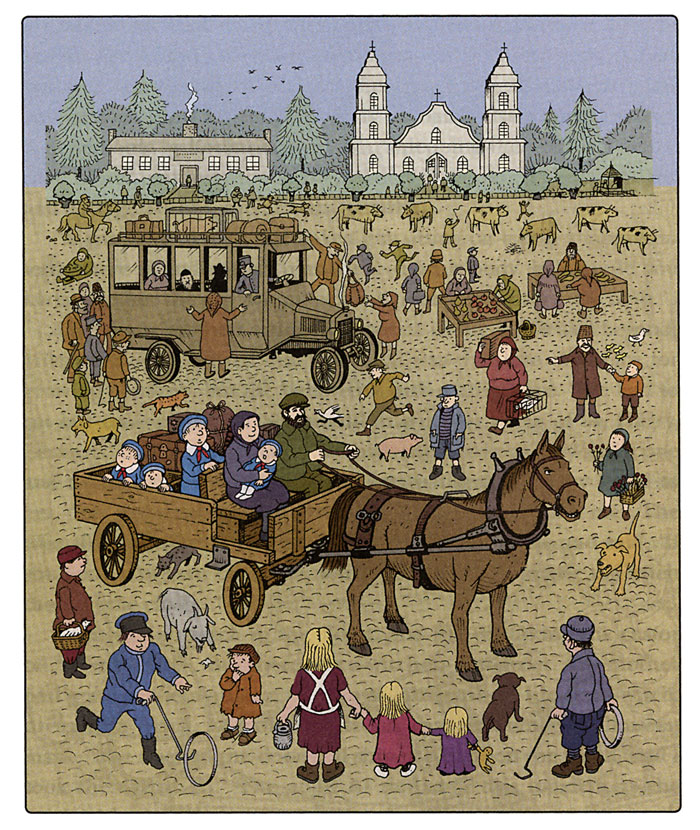

He was born Abraham Jaffee, March 13, 1921, in Savannah, Georgia. He spent his earliest years amid the wonders of Blumenthal’s Department Store, where, as the son of a successful store manager, he was allowed to roam freely. The other half of his childhood stranded him in the small, primitive town of Zarasai, Lithuania, where Jaffee’s troubled, erratic mother took him to live at the age of 6.

Jaffee’s parents were both Lithuanian immigrants to New York. His father, Morris Jaffee, arrived in 1905, and his mother, Michlia Gordon, came off the boat in 1913. Their courtship was delayed by World War I and Morris’ stay in a German POW camp. By the time of their marriage in 1919, his mother’s name had been Americanized to Milly, but, despite picking up the language quickly, she herself never became Americanized. She was deeply tied to the religious and ethnic traditions of her home country, and a move from the New York immigrant community to Georgia left her feeling even more isolated. At age 6, Jaffee already had three younger brothers. One day in 1927, his mother rounded up all four of them and took them to stay with her family in Lithuania.

Traveling by steamship to Hamburg, Germany, Mrs. Jaffee demanded that the captain stop the ship at sundown to honor the Sabbath. At the Hamburg railway station, she disappeared, leaving Jaffee pushing his youngest brother in a baby carriage through a crowd of strangers, calling for his mother while his other brothers, aged 2 and 5, wandered in different directions. “It was a moment that is as clear to me now as it was then,” he told biographer Mary-Lou Weisman (Al Jaffee’s Mad Life; HarperCollins, 2010). “I realized I must not rely on this woman for my survival.… I knew I was on my own.”

The family made it onto the train from Hamburg to Berlin, but at the Berlin station, Mrs. Jaffee refused to disembark until her children had finished their nap. Jaffee remembered his mother as a formidable figure who almost always got her way. He learned that he had to be self-reliant, because he couldn’t depend on his mother to be sensible or responsible, and he couldn’t count on his father to stand up to her. But he also learned that institutional authority—train conductors and boat captains, for example—could be defied. These were lessons that he would pass on to young Mad readers: think for yourself and don’t believe everything that your parents and institutional authorities tell you.

Jaffee’s grandfather, Chaim Gordon, was a relatively prominent figure in the Zarasai Jewish community, but his house had no running water or electricity, and shortly after her arrival, Mrs. Jaffee moved with her children to a smaller, even more austere house.

The simple, natural beauty of the countryside and the traditions of Lithuania may have fortified Jaffee against the shallow, commercial lures of modern America. But they also introduced him to leeches, poverty, lice, sub-zero temperatures and outhouses. Oppression and anti-Semitism were also in the air. Zarasai was strictly segregated, and police enforced limitations on Jewish mobility. The nearby wooded areas carried risks of being attacked by gangs of Gentile youths. To keep her children safe, Mrs. Jaffee would lock them in her home, sometimes all day, while she went out to perform acts of charity for the sick and poor and to pray at the local Orthodox synagogue.

As quoted in Weissman’s Mad Life, cartoonist Arnold Roth said, “There was always a certain sadness about Al. There were minor chords playing underneath. I knew nothing about the cause.”

Weissman wrote, “Al concealed the pain of his childhood in Lithuania like a rock in a snowball, packaging it instead as a comic myth of survival.” Jaffee rarely spoke of these experiences, and when the biography forced him to, he talked about it as though he were entertaining the listener with the adventures of Huck Finn. Thanks to his mother’s obliviousness, Jaffee, like Mark Twain’s fictional protagonist, was left to his own devices. And as with Huck Finn, his tales of youthful, humorous adventure were a thin veneer atop a shocking nightmare.

The thread that still connected Jaffee to the nation of his birth was the regular delivery of a parcel from his father containing comic strips from the American papers. When they had been together, reading from these strips had been a source of father-and-son bonding, and Jaffee continued the habit of drawing that had begun virtually as soon as he could hold a pencil.

After a year in Zarasai, Mrs. Jaffee showed no sign of bringing their stay to an end. But one day, in 1928, Al’s father showed up to take them all back to the U.S. They did not return to the same world Jaffee had left, however. Chasing his family had cost Morris Jaffee his job and most of his money. They were back in the U.S., but homeless and sleeping on relatives’ floors on the Lower East Side of New York. As the Depression took hold in 1929, unemployment skyrocketed, and the former big-time store manager was reduced to working as a part-time mail carrier.

Within a year, however, Milly Jaffee had scraped together enough money to take her four sons back with her to Lithuania, at a time when European Jews were beginning to flee in the opposite direction. The 8-year old Al, by then fatalistic in the face of his uprooting, settled back into village life. This included stealing food, and scavenging and inventing tools for entertainment as well as survival. “I became aware that I could not trust adults,” he told Weissman. “My father let me be shlepped to Europe, my mother did the shlepping. What good were adults to me? The only thing adults were good for was telling you things were sinful and trying to destroy any notions of your own. ‘You can’t do this. You can’t do that.’ I felt stifled. I developed my own brand of anti-adultism. At an early age, I set out to prove that adults were full of shit. I’m still doing that now at the age of 89.”

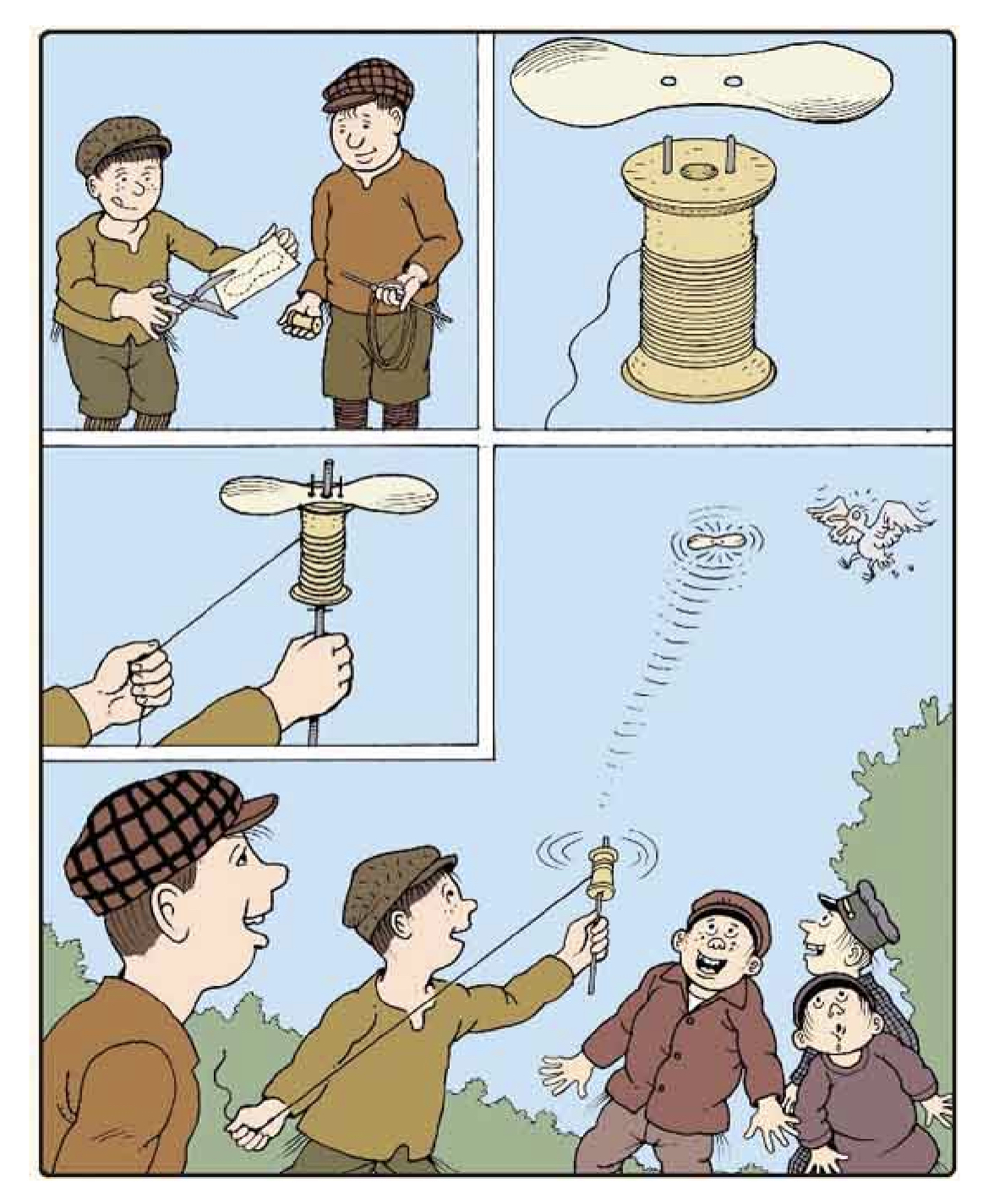

Harry, Al’s younger brother by two years, became adept at building functional toys, and Al, prefiguring his later comical blueprints for Mad, devised implements that combined hooks, lassoes and long poles for the purpose of stealing fruit. “What I wasn’t accepting was my mother’s belief that all problems would be solved if you put your faith in God because he would provide,” Jaffee told Weissman. “I began to see a lot of evidence that God wasn’t reliable. Hell would freeze over before God provided me with apples and pears.”

During their time in Zarasai, it gradually became clear that Al’s younger brother by four years, Bernard, had become deaf and mute as a result of a bout with spinal meningitis.

It wasn’t until 1933, four years later, as Hitler rose to power in Germany, that Morris Jaffee, borrowing money from his brother Harry, returned to Lithuania to try to persuade his family to come back to America. His wife refused to see him, and Al, then 12, was delegated to carry messages back and forth across a bridge. In the end, Al’s mother agreed to let Al, Harry and Bernard return to the U.S. with their father, and said she would follow in six months with her youngest child, David. She promised to see them off at the train station, but, as always, confounded by the modern world’s formalities, she arrived after the gates to the platform were locked and the train had finished boarding. “So there she is, trying to break the gate down,” Jaffee told Weissman. “The train starts to pull out, and that was the end of that. The scene is etched in my mind forever. That was the last time I ever saw my mother.”

In 1940, a few months after the Germans invaded Poland, David was brought to the U.S. The family never learned the fate of Michlia/Milly Jaffee, but she was apparently still in Zarasai when the Nazis and anti-Soviet partisans closed in on that town, shooting anyone caught fleeing. On Aug. 26, 1941, according to Nazi records cited by Weissman, “767 Jews, 1,113 Jewesses, 1 Lithuanian Communist, 687 Jewish children, and 1 female Russian Communist” from Zarasai and the surrounding area were taken into the Daugutzi Forest and executed.

The Jaffee family became further splintered by 1934, with Bernard attending the New York School for the Deaf, Harry staying with Morris’ brother Harry in Brooklyn, and Al and his father sharing a room in the East Bronx. Al became acquainted with comic books at the moment the form was born with Famous Funnies #1, and he was the first to grab the funny pages from the newspaper delivered to their boarding house. In 1935, from among students at Herman Ridder Junior High, Al was selected to take a test that qualified him to attend the newly-founded Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music and Art. Among his schoolmates at Music and Art were future Mad creators Harvey Kurtzman and Wolf Eisenberg, aka Will Elder.

Elder and Jaffee became close friends, regularly performing humorous shticks that cracked up their fellow students. They were seniors, and stars of the school’s art shows, when Kurtzman became a freshman, but Jaffee and Kurtzman immediately recognized one another’s talent. Jaffee told Weissman, “When he saw Willie’s and my work at Music and Art, he determined that someday he was going to create a humorous magazine and include us in it.”

But the Jaffee family’s debut success in the art world was achieved not by Al, but by his brother Harry. Harry latched onto the public’s growing infatuation with military planes and began drawing and painting a series of sleek, technically accurate images of Curtiss Helldivers, Martin Mariners, Lockheed P-38s and other warplanes. He found so many buyers at area department stores that he formed an assembly line that included Al, David, Bernard and Al’s friend Wolfie. Harry’s original drawing was transferred to special blue paper and different colors were added in stages by the ad hoc studio. Harry signed the art as “Jaffée.” Prints of Harry’s planes still show up on eBay and originals reportedly fetch up to $16,000 at auction.

After graduating high school, Al Jaffee was offered a scholarship from the Art Students League and admission to Cooper Union, but, tired of school and being told what to do, he turned them both down. Instead, he carried his portfolio around to comics publishers, until Will Eisner, creator of the Spirit, hired the young cartoonist to draw the humorous Inferior Man back-up series for Military Comics in 1941. Jaffee had created the concept of a mild-mannered superhero who avoided danger rather than seeking it out, but Eisner made substantial changes, including enlisting the protagonist in the Army. Jaffee didn’t enjoy taking direction from an editor any more than he had from a teacher, and he soon dropped the series, which was continued in 1943 by Al Stahl.

He found a better match a year later in future Marvel Comics superstar Stan Lee. Then writer and editor at the pre-Marvel Timely Comics, Lee wrote a back-up feature called The Imp for Captain America Comics, which he turned over to cartoonist Chad Grothkopf to draw. Grothkopf in turn paid Jaffee a lesser amount to do the actual penciling. Wising up, Jaffee approached Lee directly, and Lee hired him to work on funny animal series like Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal for Krazy Komics. Lee was creatively collaborative and editorially hands-off, a combination that suited Jaffee. One of Jaffee’s fellow Ziggy artists was Dave Berg, who had also worked alongside him at Eisner’s shop and would, like Jaffee, become one of the “usual gang of idiots” at Mad.

In 1943, surrendering to the inevitability of the wartime draft, Jaffee went into the Air Force, which he believed was safer than ground combat. Motion sickness, however, prevented him from training to become a pilot, and he was instead sent to Salt Lake City to run an art therapy program for shell-shocked soldiers. That was followed by an assignment to the Pentagon, where he created and illustrated pamphlets for a convalescent rehabilitation program and designed floor plans for the future Rusk Institute. While serving at the Pentagon, Jaffee met Ruth Alquist, a WAC from California, and they were married in 1945.

Jaffee returned to civilian life and Timely Comics in 1946. Hired by Lee as an associate editor, Jaffee storyboarded other writers’ scripts and wrote his own scripts for Super Rabbit, a character who was drawn by several artists, including Jaffee and Mike Sekowsky. Over the next three years, Jaffee fathered two children, Harry and Debbie, but was so inundated with work at Timely, storyboarding, drawing and writing a flood of titles, that by his own estimation he had little time for parenthood. Jaffee’s funny animal assignments soon began transitioning to the human-driven romantic humor of Patsy Walker, a title for which he wrote and drew seven-pagers, eight-pagers and covers. His work dominated issue after issue of Patsy, and as of 1947 grew to include six-page Jeanie stories for Jeanie Comics.

The comics boom ended at Timely in 1949, with Lee directed to lay off all creators and fill new issues with inventory stories. Within a year, however, Timely rebranded itself Atlas Comics and brought Jaffee back as a freelancer to work on Super Rabbit and many more issues of Patsy Walker. Interviewed for the 2011 TwoMorrows book The Stan Lee Universe, Jaffee told author Danny Fingeroth, “Stan said, ‘Do whatever you think is right and just bring a completely finished book.’ Which I did. I did, on average, two complete books a month for about five years.”

Meanwhile, Kurtzman had made good on his ambition to create an innovative humor comic and invited Jaffee to contribute to the recently-launched, highly-successful Mad at EC. Initially, Jaffee was reluctant to abandon the steady flow of work he was getting from Lee, but he wrote a couple of Mad features in his spare time and drew one memorable two-pager parodically depicting in slow motion the “secret” convolutions of a pro golf swing.

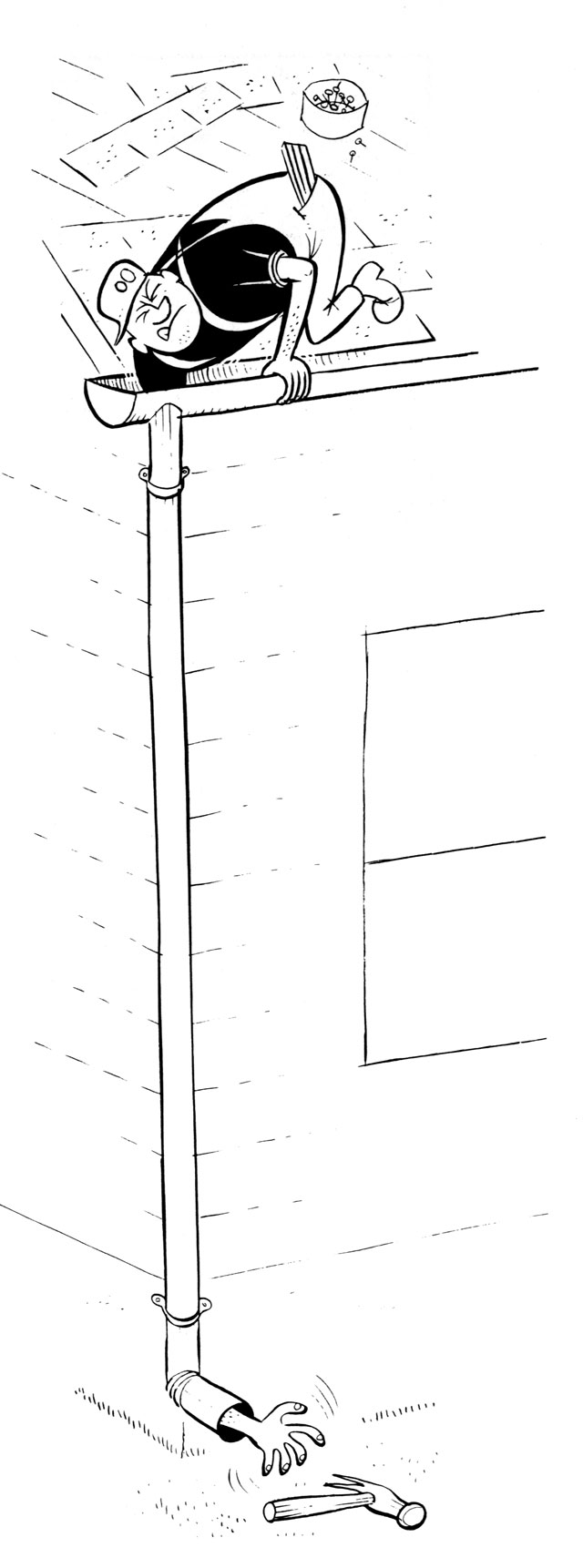

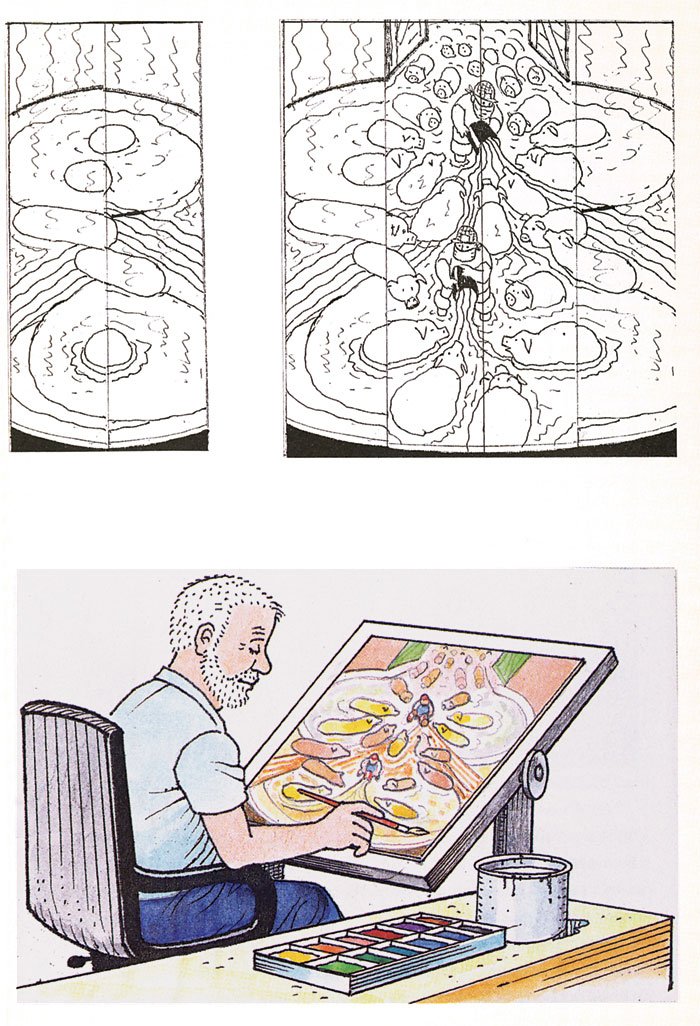

In 1956, Jaffee finally told Lee he’d had his fill of Patsy Walker and took a leap into the unknown - or actually, two unknowns. He would take a chance on Kurtzman finding enough work for him at Mad, and he would satisfy an itch he’d had since childhood to do a syndicated comic strip. Realizing that new strips had a hard time breaking into syndication, he came up with an idea that was unlike any other strip. Instead of the usual horizontal strip that led readers from panel to panel to arrive at its often verbal gag, his Tall Tales strip was a single, silent, vertical panel that invited readers to engage with it by scanning up or down to get the joke. Jaffee reasoned that the vertical shape gave editors more flexibility in finding a place for the strip, and the idea worked, beating the odds against new strips by quickly find a home at the New York Herald Tribune Syndicate. The strip eventually reached 100 newspapers and ran for six years. Its flexibility of placement, however, meant that instead of occupying a reliable destination spot amid the funnies, it was often used as filler, cropping up in unpredictable corners of the newspaper. It also suffered from editorial tampering that chipped away at its uniqueness, mutating it into a dialogue-driven gag and a Sunday version that lined up several “tall” panels into a horizontal strip. Its essential concept worn away by conventions, it faded away in 1963. (A collection was published by Harry N. Abrams in 2008.)

The strip, however, was a financial success compared to his other post-Patsy gamble. Immediately after leaving Lee and Atlas, Jaffee called Kurtzman to say he was ready to commit to Mad, expecting a jubilant welcome. Unfortunately, Kurtzman had just walked away from EC after a failed bid to gain control of the title. He had also, however, taken the cream of the Mad artists with him, intending to launch Trump, a slick new humor magazine bankrolled by Playboy Publisher Hugh Hefner. Jaffee joined the new enterprise as associate editor and contributed several pieces, but the magazine was too unique for its own good, and before it could find an audience, Hefner, who was caught in a temporary financial squeeze, pulled the plug after the second issue.

Kurtzman immediately put together another, lower-budget humor magazine called Humbug, and Jaffee, high on Kurtzman’s confidence and creative inspiration, bet his savings on it. With Jaffee and Arnold Roth as contributing associate editors, the publication struggled through two years, but came to an end in 1958.

Kurtzman and Elder went on to launch yet another ingenious, doomed humor magazine called Help!, but Roth returned full-time to his higher-paying illustration work, and Jaffee went, hat in hand, to Al Feldstein, who had taken over as editor of Mad magazine after Kurtzman’s departure. Jaffee was welcomed into the Mad fold initially as a writer, because that was what the magazine was most in need of, but Feldstein quickly realized that Jaffee was his own best interpreter.

Throughout his career, Jaffee was a cartoonist in the full sense of a writer/artist who wrote and executed his own gags. His art is so clear, and in some cases literally diagrammatic, that there is often little need for words to get the joke across. His drawings communicate instantly, inviting a viewer in with their simplicity while still packing a surprising payoff. The best example may be his famous Fold-Ins, which used words minimally, if at all, and often turned words into visual elements. At first glance, the full-page image is clearly one thing, before it becomes, just as clearly, something else.

“The Fold-In is a sort of bait-and-switch process,” Jaffee told the Washington Post in a July 27, 2017 interview. “The full-page scene asks and illustrates a question. After the page is folded, a surprise new scene and answer appears. In that way, it’s not very different from what the Republicans did during the last election with the health-care plan.”

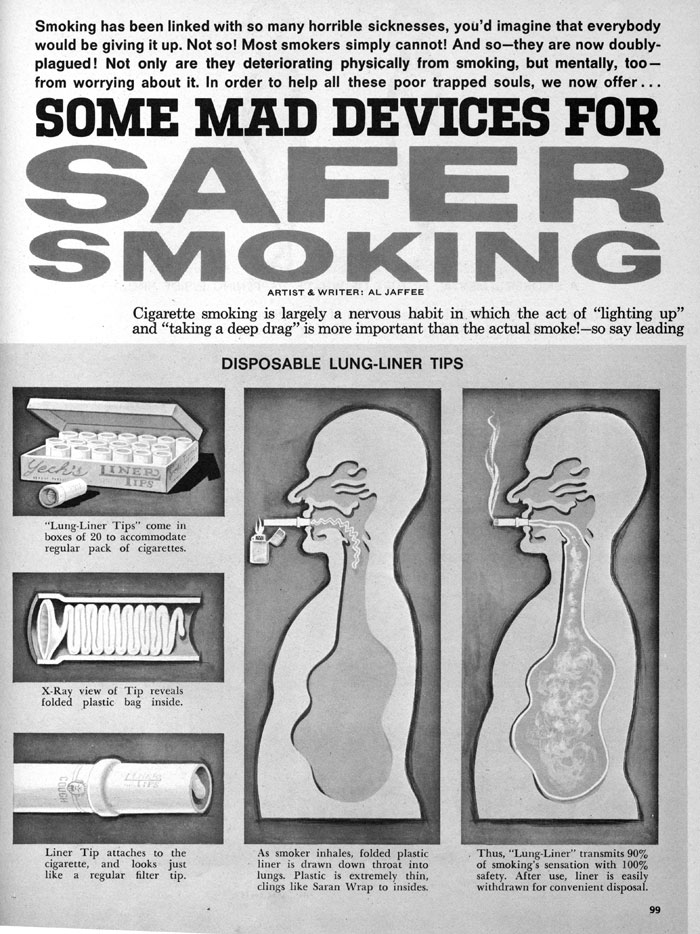

The clarity of his images may be partly due to his mechanical engineer’s awareness of how objects interact in space, something he had taught himself while stealing fruit and surviving in Zarasei. This led to several ingeniously funny Mad pages devoted to pseudo-inventions, some of which, despite their seeming absurdity, became real inventions. The designer of a patented self-snuffing cigarette, for example, thanked Jaffee for the inspiration. The 1970 paperback The Mad Book of Magic and Other Dirty Tricks was filled with Jaffee’s impossibly elaborate schematic explanations of how magic tricks are performed. Turns out the trick is more ridiculously difficult than the illusion.

Some of his gags presaged the intricacy of Chris Ware’s three-dimensional visions: one Jaffee page parodied the kid-friendly assembly projects on the backs of cereal boxes by providing instructions that resulted in the assembly of a perfect Kellogg’s Corn Flakes box.

Of his many years at Mad, where he made his greatest impression on readers, there is not much more to say. Contributors to Mad over the decades formed a repertory group, each with his (the “usual gang” consisting almost entirely of male “idiots”) own shtick. Jaffee was more versatile than most, but, like the rest, he had his regular gigs, and he fulfilled our expectations reliably and with unwavering enthusiasm month after month, year after year, decade after decade, even through Mad’s late attempts to shake things up. His Fold-In alone was a miracle of near-infinite variations on a theme. His imagination outlasted the print magazine, continuing to dream up new gags even as Mad ceased to publish regular new material in 2019. His final Fold-In appeared in the August 2020 issue in celebration of the artist’s 100th birthday.

He was an ideal guide for American kids living through the relentless sales spiel of the 1950s and 1960s. His own split childhood allowed him to always see things from an outsider’s perspective, and he had no trouble calling bullshit on the many ways that adults tried to hoodwink kids. He told Eric Spitznagel in a 2017 Vanity Fair interview: “Parents and teachers and politicians. It doesn’t matter who they are. As a little kid, if you have any kind of brain at all, you begin to see that the world operates under a very twisted set of rules. Adults tell you one thing, but then they do another.”

Though presenting himself as unsentimental and skeptical of religious faith (he had resisted going to Hebrew school as a youth), Jaffee began contributing cartoons to the Moshiach Times for Orthodox Jewish children in 1984 and never stopped. In his 80s, Jaffee reported to Weiss that he had dreamed of his mother for the first time since they were parted. Possibly as a result of narrating the story of his youth to the biographer, he dreamed he was back in Zarasai, trying to rescue his stubborn mother. He had had an opportunity to return to Lithuania in 1972 during one of Mad’s group travel vacations. Russia was on the itinerary, and Mad Publisher Bill Gaines asked Jaffee if he’d like to add a visit to Zarasai into the trip. Realizing that everyone he’d known there would be dead or gone, and any familiar buildings or homes that survived would be occupied by other people, Jaffee declined.

The Reuben Award for Cartoonist of the Year went to Jaffee in 2008. His Fold-In won a Reuben Special Features Award in 1972. He was inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame in 2013 and the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in 2014. He received four awards from the National Cartoonists Society, including its Advertising and Illustration Award in 1973, its Special Features Award in 1971 and 1975 and its Comic Book Humor Award in 1979. In 2000, he received the Harvey Recognition of Outstanding Achievement Award, and in 2001, the Harvey Award for Best Cartoonist/Writer. The collection of his Tall Tales strip received a Harvey Special Award for Humor in Comics in 2009. He won Comic-Con International's Inkpot Award in 2008. In 2011, he received the Sergio Award from the Comic Art Professional Society. On Jaffee’s 95th birthday, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio declared March 13, 2016 to be Al Jaffee Day.

In 2011, the Jeopardy game show featured a reference to Jaffee’s Fold-Ins, which may have been the honor that most impressed him. “So, no one is gonna take that away from my memory and to see people on national television immediately knowing the word fold-in," he told cartoonist Michael Kupperman in a 2011 conversation in The Comics Journal #301. “The New York Times had a fold-in crossword puzzle a couple of months ago. I have a little mark.”

Jaffee and his first wife were divorced in 1967, but he married Joyce Revenson in 1977. They remained together until her death in 2020. Al Jaffee is survived by his son, Richard; his daughter, Deborah Fishman; two stepdaughters, Tracey and Jody Revenson; five grandchildren; one step-granddaughter; and three great-grandchildren.