On December 2, 1956, readers of the Chicago Tribune found something special in their Sunday comics section—the debut of the domestic sit-comic The Gravies. This pantomime strip—soon to be as chatty as his other work—was a new outlet for the idiosyncratic soul of Dick Tracy creator Chester Gould. As one of the nation’s top ten newspapers, with out-of-town subscribers in addition to its hometown readers, the Tribune guaranteed a large readership for Gould’s new work during one of the boom periods of American journalism. Estimated daily newspaper readership in 1960—the median year of the strip—topped the 58 million mark. Sunday readership was a touch over 47 million.

The Gravies appeared only in the Tribune through its six-year run, which ended January 26, 1964. At first signed “Chet,” the early run of the strip is often solo Gould, with loose-limbed linework, sloppy lettering and other evidence of a tightly wound cartoonist blowing off steam and amusing himself. Gravies later credits the first names of Team Gould: Al Valanis, Chester's brother Ray Gould, Dick Locher, Jack Ryan and Rick Fletcher. The single-tier strip grew in 1958 to a double-decker approximately a third of a page in size.

Skewed comedy was hard-wired into Dick Tracy from its 1931 start. Gould’s fight-and-flight narratives of criminals hurtling toward claustrophobic doom, can be gripping, grotesque and deadly serious. Humor elbowed its way into the darkest storylines. Eccentric supporting characters, settings and casual commentary on current fads and foibles informs the strip. Post-war Tracy, until the end of the decade, stressed comedy over crime-solving. The popularity of the hillbilly family of B. O. Plenty, his wife, Gravel Gertie and their daughter, Sparkle Plenty (the focus of a merchandising blitz in the late ‘40s) threatened to crowd the no-nonsense Tracy out of his own strip.

The hit-and-miss humor of The Gravies was no surprise to Tracy’s Chicago readership. In the past year, they’d read a long narrative with the enigmatic Mumbles, a revived villain from a 1947 sequence, paired with a physical-culture fanatic and his feral offspring—acrobatic twin tots who vex the criminal with their anarchic slapstick mayhem. And though 1956’s Tracy narratives (which I wrote about in this essay) represent a peak year in the strip’s darkness and drama, there are also occasional moments of screwball comedy.

The Gravies' readership couldn’t have anticipated how odd the strip would be. Though its early episodes are tame, off-the-wall sight gags—some which come off like a four-color Ernie Kovacs—made The Gravies among the most eccentric strips in Trib history. With the paper’s screaming dada headlines (BELIEVE RED ROCKET DOWN! RUSH NEW ‘MOON’ ATTEMPT!) guiding their way, addled readers could hope to find comfort in the Sunday funnies.

The four-member suburban family is never given names, and Gould holds them at an omniscient remove. The connection other suburban strips made with their readers (Blondie, Hi and Lois, Gasoline Alley) is never attempted. We often feel like we’re intruding on The Gravy family rather than sharing in their antics.

Dad smokes cigars, acts on impulse, and ogles beautiful women as he dotes on his wife and kids. Mom handles Dad’s id-action with a wizened eye, chuckling as he panics, misreads and over-reacts to life’s little travails. Junior is a gag machine—a Brainiac one week, a dullard the next; whatever will sell a laugh. Sis is a cipher, there because the formula calls for two offspring.

Gould identifies with Dad, so he’s the focus of The Gravies early jokes. Dad reacts to his environment in unexpected ways:

The following three strips offer a sampler of Dad’s surrender to impulses—to the chagrin and/or mockery of his family and for our alleged amusement:

The main attraction of The Gravies, into 1958, is the loose-limbed, casual artwork of Chester Gould—freed of the oppressive blacks and intense drama of Dick Tracy. Sometimes Gould works solo, and those strips give us his only unaccompanied work of his mature period. The strip’s biggest problem? It isn’t particularly funny. "Funny-huh?!?", yes, but seldom "funny-haha". Gould seems bored with The Gravies by 1958. A dogged creator, he’d force an idea to work, no matter what. Thus, he brought in new secondary characters who took over the strip. On December 21, 1958 (“U.S. ‘TALKS’ TO SATELLITE”), Clybourne, a talking crow, enters the Gravies’ world:

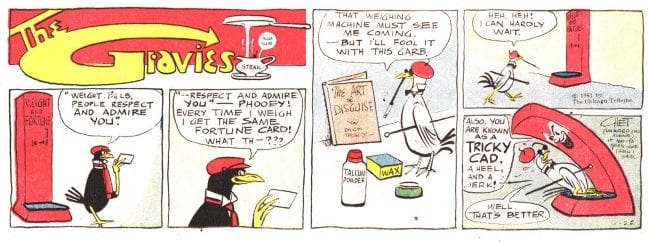

Clybourne, who acquires a spiffy tie, shirt-collar, and beret, quickly dominates The Gravies. His smart-ass personality and interactions with the family brighten up the strip.

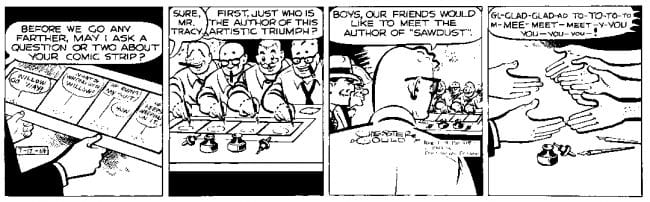

Clybourne’s antics are sometimes inspired, but The Gravies needed something else to merit the attention paid here. On September 9, 1962, Gould & Co. introduced a strip-within-a-strip-within-a-strip (accepting that The Gravies is a subset of the Sunday Dick Tracy in the Tribune). Two weeks before this blessed event, Gould gives the reader a warm-up curveball:

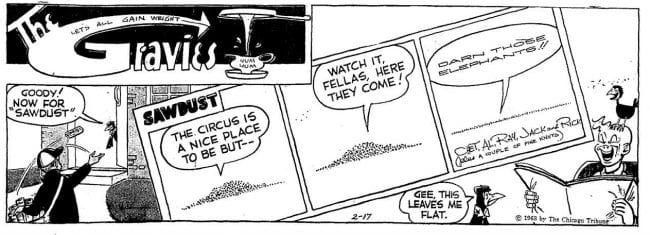

Zany things had happened before in The Gravies, but meta-humor wasn’t a part of its vibe. Two Sundays later, Chicagoans got a handful of sawdust thrown in their face:

By the end of the 1950s, humor strips had begun their domination of the newspaper comics page. Though continuities like Tracy still had a strong readership, visually sparse strips—a campaign led by Charles Schulz’s Peanuts—had growing reader appeal.

Old-timers like Gould, who labored over complex visual details as page space for their work shrunk, post-WWII, were bemused by these “easy” humor strips. Their criticism mistook the effort involved. Charles Schulz obsessed over his daily strip just as Gould did with Tracy, and put a comparable amount of labor into his artwork.

With the threat of radio and television news, which could scoop newspaper headlines in a split second, dailies had to work harder and faster. Corners cut on printing quality meant that a paper could zip through the printing process and be in its reader’s hands while the news was still news. Reproduction suffered: once-crisp screened photos became blotchy; delicate graphic lines clogged with ink. It was good for news but hell on the comics.

Smaller and poorer reproduction favored simpler visuals; Gould gave in by 1967. His Tracy panels used bolder lines, fewer words and detail. It offered different opportunities—to make bolder visual choices and to heighten the always-present Expressionist tendencies in Gould’s cartooning eye. Here is a 1970 daily and a ’69 Sunday with the new, strippeddownTracy look:

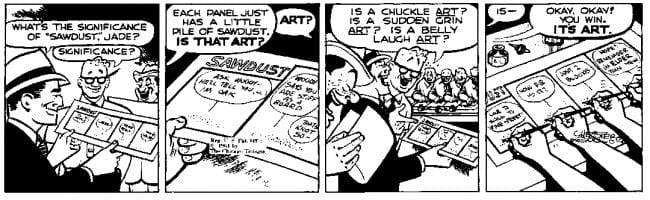

Gould’s reactionary swipe at the Peanuts- era of comics was Sawdust—a strip-within-a-strip about… well, sawdust. The Gravies, with occasional reprieves into barnyard humor and domestic gags, became about the family’s—crows included—addiction to Sawdust’s woodwork of willowy puns. Gould sold his humor hard. If he thought an idea was funny, you were going to laugh along with him, like an obnoxious uncle telling jokes at a family get-together. Thus, The Gravies turns into a single panel in three acts: a prelude to the reading of Sawdust: the Sawdust strip, with its knotty plank of wordplay; the after-strip ecstasy, as its readers gasp for breath and repeat ritual post-coital phrases (“Mama, I think I’m going to faint;” “I don’t get it;” and, at least once, Gould’s baby-talk mantra, “Zscpjs.”)

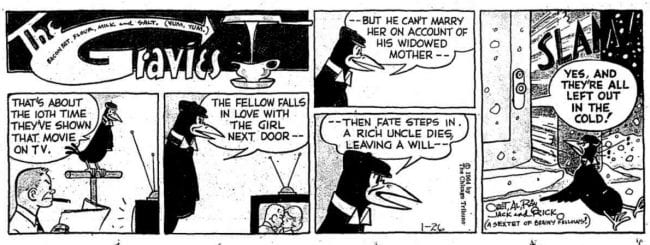

Now a ping-pong of Sawdust worship sessions and “crow-educational” gags, The Gravies continued until January 26, 1964.

The sassy Clybourne got the boot in the final strip. The Gravies vanished with no fanfare. It was replaced by advertisements. (The strip was bumped several times through its run to make room for front-page advertising—sometimes for new strips added to the Trib’s Sunday line-up.)

Gould worked a talking, cigarette-smoking raven into a 1963 Dick Tracy continuity. It was inevitable that Sawdust, obviously dear to Gould’s heart, would survive the end of The Gravies.

1964 was a controversial year for Dick Tracy. During the intense, brutal 52 Gang sequence, which ran from August to December 1962, Gould introduced outer-space themes to his police procedural. This was a jarring move for his readership. Gadgetry and techno gimmicks were vital to Tracy from the 1940s on. The concept of a magnetic space coupe, made of titanium and asbestos and capable of rapid, silent travel to and from the moon in an hour’s time, was a stretch for earthbound readers. Was Dick Tracy still a crime strip? Was it science fiction? This fascinating transition is captured in Volumes 20 and 21 of IDW/Library of American Comics’ ongoing hardcover reprint of Gould’s Tracy. The mid-1960s Tracy has Gould fans divided. Some despise the Moon/SF sequences. Others treasure them as acute examples of Gould’s wild imagination, off-kilter sensibilities and a penchant for shocking and befuddling his readers. These books have become more important, as this period had been unread since its original printing, half a century ago.

Amidst Moon Maid, wrist TVs and other wild concepts of Tracy ’64, the Sawdust narrative is interrupted at its May 1964 opening, after Sam Catchem, supervising the removal of dead trees in a stately neighborhood, discovers a human skeleton hidden in a wired-together section of a decrepit elm.

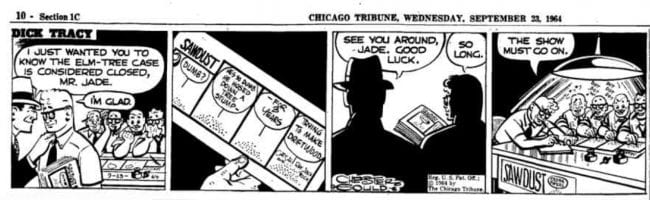

Tracy is off to the Moon, with industrialist Diet Smith, as they discover living beings in a tropical valley concealed inside a fissure on the Moon. By July, Tracy is at last on the case. Clues lead him to the home of cartoonist Chet Jade, creator of Sawdust, and an obvious self-parody.

Jade doesn’t draw or write Sawdust. He has a staff of four artists—each assigned to make the numerous dots needed for each panel. The quartet hunch, shoulder over shoulder, at a long drawing board and mindlessly chant “dot dot dot dot dot” as they draw. Jade cheerfully micro-manages his art quartet (whom I assume are caricatures of Gould’s assistants):

When the integrity of Sawdust is questioned by Tracy, Gould speaks through Jade:  Though Tracy rolls his eyes at Jade’s gosh-gee enthusiasm, he tolerates the cartoon artisan, who soon hires Moon Maid as a gag writer at $20 per idea--$157 adjusted to 2017 dollars. The mystery of the skeleton-in-the-tree involves Jade, who has spent his adult life hiding a horrible secret (none of which I wish to spoil for you, as added in an inducement to acquire this volume).

Though Tracy rolls his eyes at Jade’s gosh-gee enthusiasm, he tolerates the cartoon artisan, who soon hires Moon Maid as a gag writer at $20 per idea--$157 adjusted to 2017 dollars. The mystery of the skeleton-in-the-tree involves Jade, who has spent his adult life hiding a horrible secret (none of which I wish to spoil for you, as added in an inducement to acquire this volume).

Magnetic air cars acquired from the hot-tempered Governor of the Moon help Tracy and his team solve this murder mystery. Jade is exonerated, and our final glimpse of the Sawdust crew is intentionally melancholic:

Chester Gould couldn’t let go of a good idea, and we see glimpses of Jade and his crew from time to time as Sawdust goes into the background of Dick Tracy’s world. Here’s a Sawdust gag from 1966, written by Rick Fletcher, who would assume the art reigns on Dick Tracy after Gould’s late 1977 retirement. I wonder if he got $20 for this idea?

Gould’s next meta-strip would appear in 1969, when egotistical cartoonist Vera Alldid and his strip The Invisible Tribe—which has nothing but white space and large speech balloons— throws another eccentric wrinkle into the ever-fascinating fabric of Dick Tracy.

Thanks to Ger Apeldoorn and Dean Mullaney for their help in supplying images.