One of the interesting things about reading current comics is the truly international reach that small press artists now have. Thanks in large part to the internet, artists have a chance at reaching audiences from across the globe. It's not just the web, however—in what seems like a fulfillment of Dylan Horrocks's Hicksville, minicomics and handsome books are appearing from countries not necessarily known for their alt-comics scenes. In this column, I'll be looking at comics by cartoonists from Poland, Latvia, England, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Turkey. (I'm still waiting for the Mongolian mini-comics mentioned in Hicksville to show up on my doorstep.) As a critic, I feel lucky that English's status as the cultural lingua franca encourages cartoonists to write in English or at least provide translations.

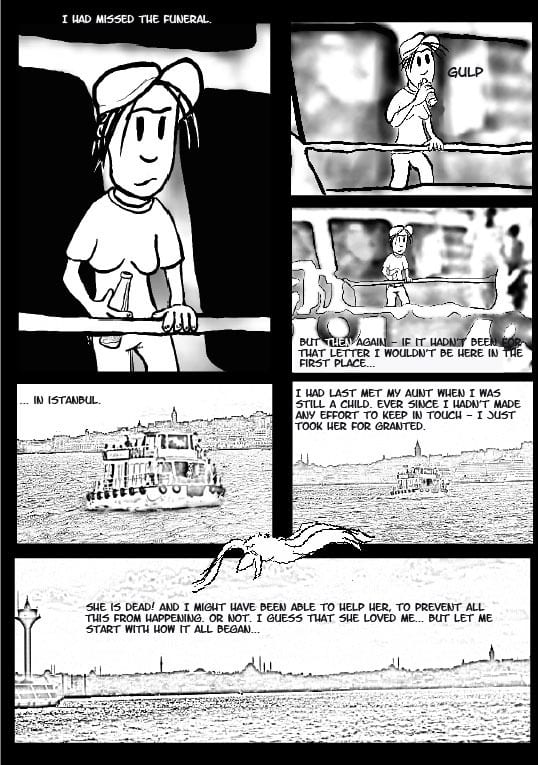

Zakkum (Turkish for "oleander") is the first comic by German visual artist Beldan Sezen, who currently makes Amsterdam her home but is of Turkish descent. It's published by the British concern Treehouse Press, and is part of a trend that includes many of the comics in this survey: multinational cooperation and outreach in the search for new talent. This 45-page "graphic murder mystery" starts with a character (who is basically a fictional stand-in for the author) receiving a package from an aunt back in Turkey who believes she's in danger, and then receives word from home that the aunt is dead. Sezen creates her own particular brand of noir with simple, chunky, and powerful figures. She then uses washed-out photographs and collages to create her backgrounds, evoking noir without resorting to visual cliches. For night scenes, she employs double-exposed photographs to create light-on-black backgrounds. For action scenes, she uses icons to depict dialogue to keep the reader moving quickly from image to image. There's a series of pages where the narrator goes from explaining how she wants to dig up the body of her dead aunt to doing so with a friend (praying to Allah all the way) to falling into bed with her ex to trying to make herself heard in an Istanbul gay dance club. Sezen's ability to speed up and slow down her pacing as needed makes this a satisfying read.

Sezen's narrator makes for an unusual protagonist, especially as certain things about her sexuality that seem to be implied become explicit halfway through the story, turning the noir detective stereotype on its ear. While possessing a decidedly feminine body, the narrator's style of dress and swagger make her a fitting hard-boiled detective, even as she has to navigate the conservatism of Istanbul. Halfway through, she even meets up with her own femme fatale of sorts, though her ex-girlfriend winds up being one of the keys that cracks the case. Queer identity enters the story as what appears to be a side distraction, then winds up being the key not only to the murder mystery but also to the secondary twist that accompanies the epilogue. Sezen cleverly puts together the clues for the reader, using a key linguistic distinction to divert attention from a set of clues, and leaves the reader as aghast as the narrator at the end, when the real identity of the killer is revealed. Sezen plays against the hipness and self-righteous awareness of her detective in regards to her sexuality, which winds up leading to her downfall. There's a lot going on in this short comic that obliterates the boundary between genre work and personal work.

Sezen's narrator makes for an unusual protagonist, especially as certain things about her sexuality that seem to be implied become explicit halfway through the story, turning the noir detective stereotype on its ear. While possessing a decidedly feminine body, the narrator's style of dress and swagger make her a fitting hard-boiled detective, even as she has to navigate the conservatism of Istanbul. Halfway through, she even meets up with her own femme fatale of sorts, though her ex-girlfriend winds up being one of the keys that cracks the case. Queer identity enters the story as what appears to be a side distraction, then winds up being the key not only to the murder mystery but also to the secondary twist that accompanies the epilogue. Sezen cleverly puts together the clues for the reader, using a key linguistic distinction to divert attention from a set of clues, and leaves the reader as aghast as the narrator at the end, when the real identity of the killer is revealed. Sezen plays against the hipness and self-righteous awareness of her detective in regards to her sexuality, which winds up leading to her downfall. There's a lot going on in this short comic that obliterates the boundary between genre work and personal work.

That a British concern published an artist from the Netherlands should not be surprising. International lines are often blurred and altogether absent in many of these comics. For example, the third issue of the New British Comics anthology is edited by Polish national Karol Wisniewski, who publishes each issue in both English and Polish. His time spent in the U.K. inspired him to create this anthology, which is solid if generally unremarkable. There's not much rhyme or reason to its contents, other than the way they display the variety of comics available in Britain. The thin line of Paul O'Connell is a pleasure to see in strips about Alfred Hitchcock as a practical joker and a bumbling handyman whose mere presence causes chaos. The Scottish team of Craig Collins and Iain Laurie contribute the latest in their humorous, Lovecraft-influenced horror stories about an old man who hears the call of an ancient threat, grudgingly puts on a mask, grabs an axe, and goes to his basement to deal with it. Laurie's line possesses a quiet intensity marked by an almost pointillist quality that is contrasted by blunt uses of black.

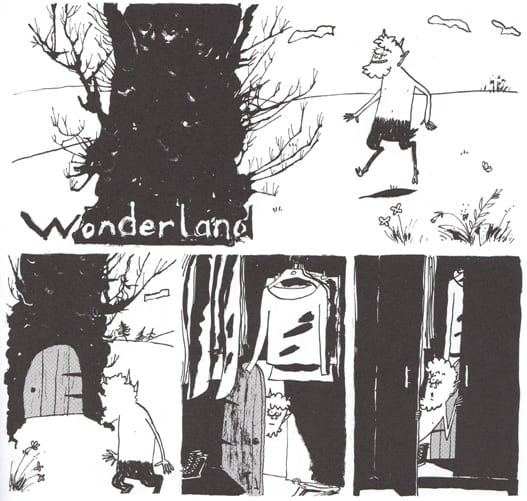

Wilbur Dawbarn's story about a satyr happening upon a young woman by way of a secret closet is sweet and touching, thanks in part to the way his art looks a bit like a cross between MAD artists Don Martin and Sergio Aragones. Dawburn does give the satyr a bit of a shock at the end in a story that's entirely wordless, yet flows easily because of Dawburn's character work and body language. Van Nim's "Crack" starts off as a first-person broken heart/abusive relationship story, drawn in an overtly cute style reminiscent of a children's story. In the span of a few panels, Nim fully recontextualizes these characters in a disturbing manner, placing the story still in the realm of kid-lit but with an ending that's far from happily ever after. The state of anthology comics in England is certainly impressive, given that this low-fi effort maintains a strong level of quality throughout, even if some of the stories aren't especially innovative.

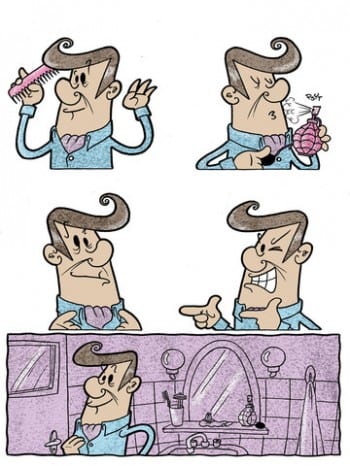

Speaking of Poland, the Bartosz Sztybor/Piotr Nowacki collaboration Tainted is an enjoyable, wordless effort reminiscent of Lewis Trondheim's work. Nowacki's rubbery, cartoony line and the bold color choices of the coloring team are a nice balance for this series of short stories involving doomed relationships. Some of these strips are pretty obvious, as when a spiked round creature falls in love with balloon creatures with tragic results. Only the  masochism causing him to fall in love with another spiked creature gives the creature a happy (albeit bloody) ending. My favorite strip involves a sleazy, middle-aged club-goer who primps for his date (and winks in the mirror while "shooting guns" with his fingers), gets her to smoke cigarette after cigarette resulting in her death, and then removes his mask at home to reveal himself as the Grim Reaper--giving himself that same wink. The book concludes with a young fireball and a young ice cube who fall in love with each other but face the classic Romeo & Juliet dilemma. Of course, their relationship is exacerbated by the fact that their merest embrace is lethal to the other. Neither the insights nor the laughs are at Trondheim's level, but this is a visually appealing, clever comic whose gags are frequently smart and whose design is impeccably beautiful.

masochism causing him to fall in love with another spiked creature gives the creature a happy (albeit bloody) ending. My favorite strip involves a sleazy, middle-aged club-goer who primps for his date (and winks in the mirror while "shooting guns" with his fingers), gets her to smoke cigarette after cigarette resulting in her death, and then removes his mask at home to reveal himself as the Grim Reaper--giving himself that same wink. The book concludes with a young fireball and a young ice cube who fall in love with each other but face the classic Romeo & Juliet dilemma. Of course, their relationship is exacerbated by the fact that their merest embrace is lethal to the other. Neither the insights nor the laughs are at Trondheim's level, but this is a visually appealing, clever comic whose gags are frequently smart and whose design is impeccably beautiful.

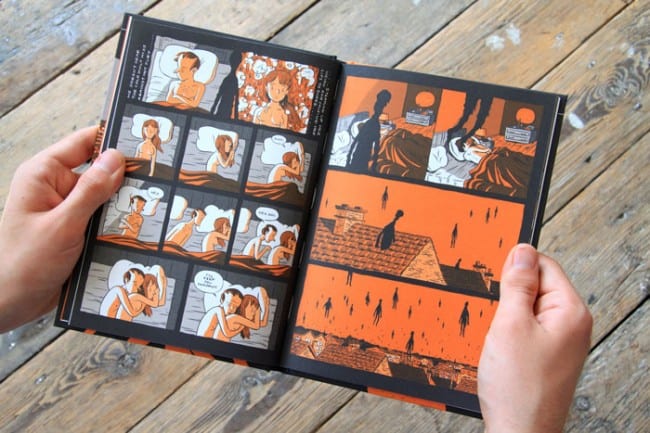

Going back to England, Luke Pearson's first full-length comic not aimed at an all-ages crowd is Everything We Miss (Nobrow). There's a lot to admire about this comic, including Pearson's impeccably beautiful line and use of color to heighten emotion. Unfortunately, the emotion Pearson chooses to heighten is pure misery. The book is about the end of a relationship and the many tiny moments and things said and left unsaid that could have saved it. Pearson injects a fantasy element into the story and is able to redeem it thanks to that device, as he posits that there are magical and monstrous forces surrounding humanity at all times that we can't quite see. Shadowy monsters pass through us and force people's jaws and tongues to say hurtful things (after that particular scene, Pearson brilliantly then pulls back to reveal thousands of these shadowy creatures emerging from houses). Little monsters observe our every move out of curiosity but do nothing to intervene. In the best scene in the book, a series of people who might be redeemed if only they had noticed a particular person looking at them instead miss their opportunities and are sentenced to live miserable lives. Other than the slight note of hope at the end of the book, Pearson really lays it on thick here, as the misery he depicts frequently threatens to turn into mawkishness. Given the restraint he shows in his other comics, I was surprised to see how hard he hammers the reader in this book. For whatever reason, his all-ages Hilda books seem to force him to balance his approach a bit more.

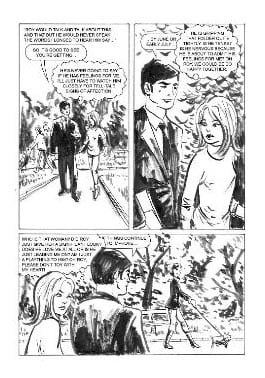

The comics scene in Ireland, artist John Robbins tells me, is self-contained and doesn't overlap much with the British scene. If it's small, there's still a lot of talent and wit to be found in its alt-cartoonists, as the anthology Romantic Mayhem Pocket Book demonstrates. It's a bit odd to pick up a comic done by artists from a particular country that's entirely a lampoon of a very specific, very American kind of comic: old-fashioned romance books. Most of the stories here play these tropes for laughs while mimicking the visual style quite adroitly.

For example, in "What's Roy Thinking", Paddy Brown does a spectacular Alex Toth approximation while writer Gar Shanley turns one woman's paranoia into an appropriately high-stakes punchline. Archie Templar and Shanley's "Why Don't You Call" uses Zip-A-Tone and other effects to look like a deliberately old comic that resolves in much the same way as the first story. Ian Pettitt's "Perfect Nadine" is an Al Hartley pastiche, complete with a garish four-color palette and a simple line. Robbins's own "All The Way" turns around virginity-loss panic into something sweeter and more tender. The only story that really delves into weird territory is Ronan Kennedy's "Unhappy In Love", a story about a young girl who falls in love with the dashing and suave growth on her leg. The flatness of the visuals remind me a little of Michael Kupperman, but there's a real sense of sincerity about the poor girl's dilemma despite all of the body transformation humor. All told, it's another solid (if repetitive at times) anthology that's hard to distinguish from the average American collection. Of course, this book is deliberately satirizing a particularly American comics genre, but the point of view in doing so doesn't seem to be a specifically Irish take (or any kind of take, for that matter).

On the other hand, Latvia's Kus! series features an aesthetic that's sharply different from that found in most American anthologies. It's a determinedly international anthology, and issue #8 features creators from Poland, Germany, Japan, Mexico, Finland, Sweden, Switzerland, Belgium, France, the USA, and Lithuania. There's a heavy focus on Baltic and Scandinavian countries, as one might expect, but the imperative to feature a wide variety of styles that are truly different is obviously one of the anthology's missions. For example, the theme of the issue is a specific one: "allotment gardens," or what's known as a community garden in the U.S. (though they are more common in Europe). The book starts with a photo of a typical allotment: a small, measured-off area that is not unlike the page of a comic book in terms of its strict, panel-like arrangement. Koshi Kawachi takes that idea a step further in the photo that ends the comic, "MANGA Farming", where plants literally grow out of comics placed in trays with water, all arranged in neat rows.

On the other hand, Latvia's Kus! series features an aesthetic that's sharply different from that found in most American anthologies. It's a determinedly international anthology, and issue #8 features creators from Poland, Germany, Japan, Mexico, Finland, Sweden, Switzerland, Belgium, France, the USA, and Lithuania. There's a heavy focus on Baltic and Scandinavian countries, as one might expect, but the imperative to feature a wide variety of styles that are truly different is obviously one of the anthology's missions. For example, the theme of the issue is a specific one: "allotment gardens," or what's known as a community garden in the U.S. (though they are more common in Europe). The book starts with a photo of a typical allotment: a small, measured-off area that is not unlike the page of a comic book in terms of its strict, panel-like arrangement. Koshi Kawachi takes that idea a step further in the photo that ends the comic, "MANGA Farming", where plants literally grow out of comics placed in trays with water, all arranged in neat rows.

Ruta Briede's "Sweet Little Things About Solitude" is one of many strips that includes mention of a garden gnome, as it seems clear that many of the cartoonists were seeking some common garden item to build a story off of. Her story looks assembled as much as it is drawn, with a deep green background that resembles construction paper. Her protagonist takes a tray of soil with a red triangle pointing out of it, plants it, and watches it grow into a gigantic garden gnome that he then stands on top of--presumably to get away from it all. The anthology shifts styles in a jarring manner, going from Ingrida Picukane's painterly style in a story whose title is built off of an untranslatable Russian haiku to the more naive style of Ernests Klavins to the highly stylized illustrations of Philip Janta.

A few other pieces in particular caught my eye. Liesbeth de Stercke's "Schreber Garten" is one of the most beautiful pieces in the book, as it combines her expressively scribbled drawings with colored pencil to create something both naive-looking and sophisticated at the same time. A Lithuanian cartoonist named Yoshi contributes an explosion of color that's part Fauvian and part psychedelic about garden gnomes being kidnapped and "committing suicide," as staged by the

titular Garden Gnome Liberation Front. It's a very witty take on both culture and police-procedural stories. Hironori Kikuchi's story plays on typical manga tropes and amps them up furiously in a whirlwind of color, as the artist himself starts to negatively affect his characters when he drinks beer while drawing. While the narrowness of the theme leads to some repetitiveness (even though some of the cartoonists wander far off from it), there's no question editor David Schilter has a tight hand on the direction of this book. It's the most exciting, varied and challenging of all the international anthologies I've read, and that obviously comes down to Schilter's doggedness in seeking out young cartoonists and giving them a top-notch venue to grow.

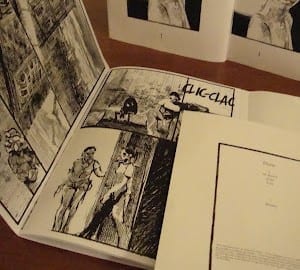

The final cartoonist on my survey is Dutch artist Ibrahim R. Ineke. I've been reading his Gothic horror comics for quite some time, and his background as a painter is evident in the way each individual image is meant to strike the reader in a manner very much removed from the typically fluid nature of comics. He told me that in his comics, he's not so much interested in the relationship between outsized emotion and environment that's typical of Gothic horror, but rather the more contemplative aspects of such literature. In particular, he zeroes in on the way decay plays a huge role in such fiction, and that contemplation of that eventual decay that is also a standard part of the genre is really contemplation of the void.

That's why his cover version of the old Wally Wood story "Sanctuary" is so interesting. The story about a king who demands that a tower be built for him to protect him from his enemies, only to wind up as an elaborate tomb, is first presented as the king's mind decaying and seeing rot all around him. After he's dead, his invincible tower also wastes away. Ineke is all about using blacks, with an intense scribbly line altered with white-out to create light affects and then distorted using a photocopier. I've never seen an artist use that light and image distortion from a copier to such interesting effect, but the decay of the image itself through multiple reproduction fits right in with his project.

That's why his cover version of the old Wally Wood story "Sanctuary" is so interesting. The story about a king who demands that a tower be built for him to protect him from his enemies, only to wind up as an elaborate tomb, is first presented as the king's mind decaying and seeing rot all around him. After he's dead, his invincible tower also wastes away. Ineke is all about using blacks, with an intense scribbly line altered with white-out to create light affects and then distorted using a photocopier. I've never seen an artist use that light and image distortion from a copier to such interesting effect, but the decay of the image itself through multiple reproduction fits right in with his project.

Scarlet Dub is a more immediate example of this style, as he takes a page from colleague Mark Mattijs van Katwijk and uses a photocopier to warp images and emphasize the darkness suggested by the snippet's text. Kat Abasis is a retelling of the myth of Orpheus that emphasizes the bleak darkness of the walk into Hades, the sheer sense of hope-snuffing void that he must navigate until he loses his love. All Dem Witches is another collaboration with van Katwijk where Ineke starts with a public hanging and ends with child sacrifice, though the precise details of what's going on are obscured, with flashes of light illuminating horrified facial expressions. This seems to be the most conventional of his comics in terms of the imagery. The most ambitious of his comics is the first issue of Eloise, which eases off on the darker backgrounds in favor of his furious scribblings, until the title character is faced with an assault that she must react to. There, black becomes the background color and white-out delineates the combatants. Ineke slides his character in and out of reality, suggesting someone who's either mentally ill or else slipping between a fantasy world and the real world. Each one seems to be equally terrifying in their own way, as the issue sees her sitting at a bus stop, seeing monsters as boys and vice-versa. This comic balances Ineke's need to create an opaque narrative with creating a structure study enough to build a long story around.

Scarlet Dub is a more immediate example of this style, as he takes a page from colleague Mark Mattijs van Katwijk and uses a photocopier to warp images and emphasize the darkness suggested by the snippet's text. Kat Abasis is a retelling of the myth of Orpheus that emphasizes the bleak darkness of the walk into Hades, the sheer sense of hope-snuffing void that he must navigate until he loses his love. All Dem Witches is another collaboration with van Katwijk where Ineke starts with a public hanging and ends with child sacrifice, though the precise details of what's going on are obscured, with flashes of light illuminating horrified facial expressions. This seems to be the most conventional of his comics in terms of the imagery. The most ambitious of his comics is the first issue of Eloise, which eases off on the darker backgrounds in favor of his furious scribblings, until the title character is faced with an assault that she must react to. There, black becomes the background color and white-out delineates the combatants. Ineke slides his character in and out of reality, suggesting someone who's either mentally ill or else slipping between a fantasy world and the real world. Each one seems to be equally terrifying in their own way, as the issue sees her sitting at a bus stop, seeing monsters as boys and vice-versa. This comic balances Ineke's need to create an opaque narrative with creating a structure study enough to build a long story around.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the comics in this survey reference American genre or cultural tropes. Sometimes the inspiration is directly related to specific comics, and in other instances it's Western culture in general. I'm not sure if the artists reference American culture as a way of reaching out to American readers or if they're simply interested in exploring a particular influence; I would imagine it's a mix of both for any cartoonist who bothers to do a comic in English. It is encouraging to read anthologies like Kus!, which don't pander in the least to an American audience, and encourage their participants to do what they do best. As a reader and critic, I'm always grateful for that sort of comic, one that I have to carefully examine in order to draw out its meaning and attempt to understand its context.