From The Comics Journal #116 (July 1987)

Riding the crest of DC’s explorations of the adult comics market in ’86 and ’87 was Watchmen, perhaps one of the most thoughtful renditions of the superhero genre. Scheduled to finish its 12-issue run this summer, Watchmen has shown comics fans and professionals alike that a comics series employing literary techniques — such as the layers of theme and plot inherent in each issue, the intricate and precise attention to detail evident not only in the writing, but also in the artwork, and the desire to portray the genuine crises the world faces today — could be both a commercial and a creative success. The following is a discussion on the influences and thought behind Watchmen between series creators Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons at the UK Comic Art Convention in London on Sept. 21st, 1986. Moderating the panel discussion is British comics writer Neil Gaiman.

NEIL GAIMAN: I thought I’d start off by asking Alan and Dave a couple of questions about the genesis of Watchmen — how it started out way back when Alan was asked to do something with some Charlton superheroes, and how it evolved into the rather remarkable comic it is now.

ALAN MOORE: We weren’t asked to do anything with the Charlton superheroes. I just thought that they were all lying around, up for grabs, and I hadn’t heard of anything else that was being done with them. They were just a nice, innocent little bunch of characters, which is always fair game, really, and there was a self-contained universe with four or five characters, and I thought it’d be nice to just take that and do whatever you wanted with it. So I started mapping out a few ideas, and originally it was just a murder mystery, “Who killed the Peacemaker,” and that was it. We sent all this stuff to Dick Giordano and some of it was extreme. We were going to treat the Question as a lot more extreme than he’d been treated before. Dick loved the stuff, but having a paternal affection for these characters from his time at Charlton, he really didn’t want to give his babies to the butchers, and make no mistake about it, that’s what it would have been. He said, “Can you change the characters around and come up with some new ones?” At first I wasn’t sure whether that would work, but when Dave and I got together and started just planning these things out, it all really snapped into place and worked fine. I’m much happier now doing it with original characters. It’s worked out much better than it would have done if we had used Captain Atom, Blue Beetle, and all the others, and I’m pleased with it. Me and Dave have been wanting to do something together for a long time, so when this came up I said I’d be happy to work with Dave and Dave said he’d be happy to work with me and that’s it.

ALAN MOORE: We weren’t asked to do anything with the Charlton superheroes. I just thought that they were all lying around, up for grabs, and I hadn’t heard of anything else that was being done with them. They were just a nice, innocent little bunch of characters, which is always fair game, really, and there was a self-contained universe with four or five characters, and I thought it’d be nice to just take that and do whatever you wanted with it. So I started mapping out a few ideas, and originally it was just a murder mystery, “Who killed the Peacemaker,” and that was it. We sent all this stuff to Dick Giordano and some of it was extreme. We were going to treat the Question as a lot more extreme than he’d been treated before. Dick loved the stuff, but having a paternal affection for these characters from his time at Charlton, he really didn’t want to give his babies to the butchers, and make no mistake about it, that’s what it would have been. He said, “Can you change the characters around and come up with some new ones?” At first I wasn’t sure whether that would work, but when Dave and I got together and started just planning these things out, it all really snapped into place and worked fine. I’m much happier now doing it with original characters. It’s worked out much better than it would have done if we had used Captain Atom, Blue Beetle, and all the others, and I’m pleased with it. Me and Dave have been wanting to do something together for a long time, so when this came up I said I’d be happy to work with Dave and Dave said he’d be happy to work with me and that’s it.

DAVE GIBBONS: Yeah, I’ll go along with that. People ask me how I got involved in it, and I can’t really remember. I remember Alan sending me a synopsis. We’d done quite a lot of things that we’d tried to get done with DC — we were going to do Martian Manhunter and Challengers of the Unknown, and some of the aspects of that led into Watchmen.

MOORE: Some of them, yeah. There were projects that we’d talked up that we both wanted to do, and it all just came out. The thing was that with Watchmen if you read that original synopsis it’s the bare skeleton. There’s the plot there, but it’s what’s happened since then that’s the real surprise because there’s all this other stuff that’s crept into it, all this deep stuff, the intellectual stuff. [Laughs.] That wasn’t planned. The thing seems to have taken on an identity of its own since we kicked it off, which is always nice.

GAIMAN: How much feedback is there between the two of you to create what we see now?

GIBBONS: Alan did quite a detailed synopsis plot-wise, but I visualized it first as being the Charlton characters, but I seem to remember as far as the design of the characters goes Alan came up with the names and a sort of character description, but not anything specific about how they would dress. I didn’t actually sit down and say, “I’m now going to design the Watchmen.” I did it at odd times and spent maybe two or three weeks just doing sketches. There was one day that Alan came to my house, and we spent the day going through the sketches and talking about possibilities. To me now it seems like the Watchmen have always been there. Because we’ve done so much with them since that, I’m hazy about where they came from.

MOORE: When me and Dave fall out in a couple of year’s time, this is the sort of thing we shall argue about. There’s little things like … when did we decide not to put any clothes on Dr. Manhattan? We were talking about it and I remember saying, “Will they let us get away with that, just not putting any clothes on him?”

MOORE: When me and Dave fall out in a couple of year’s time, this is the sort of thing we shall argue about. There’s little things like … when did we decide not to put any clothes on Dr. Manhattan? We were talking about it and I remember saying, “Will they let us get away with that, just not putting any clothes on him?”

GIBBONS: “Shall we? Yeah.” And in fact, no one has made any objection to that.

MOORE: It looks so innocent. If you make it coy, then it looks weird, but if he’s just walking around stark naked and nobody’s taking any notice of it then somehow it does look really innocent. We’ve got male full-frontal nudity in issues # 3 and #4, and you don’t even notice it, really. It’s there, but so what, it’s really casual.

GIBBONS: I was looking at some of the original sketches the other day, and many of our first ideas have made it through. The ads that DC have run for the Watchmen come from little doodles Alan did on the day that we spent together, and they are just copies of what we ended up with. The whole look and design of the book with the clock going round and everything is our primal instinct with very little compromise.

GAIMAN: What was DC’s reaction to a book that didn’t have people fighting on the cover and a plot with people dripping blood and so forth?

MOORE: There’s bound to be a certain amount of nervousness, but to DC’s credit they backed us all the way on it. It could be said that it’s commercial suicide just having a badge on one cover, a statue on the next cover, a radiation symbol on the third one and so on, and it was a new title with no known super-heroes in it. You’re going to sell a few copies on me and Dave’s names I suppose, but there’s nothing else there that’s going to grab the reader. You’ve got the title on sideways so that it’s not always easy to see it on the racks if they don’t have flat displays, but DC could see what we were doing, that we were trying to produce a package that looked radical, that was maybe going to interest people who weren’t interested in comics, that you could put out in Waldenbooks or something like that and people would say, “Oh, this doesn’t look like a comic. I’ll buy it.” DC backed us all the way on that and have been really supportive about even the most grotesque excesses.

GIBBONS: I remember the covers in particular. We hemmed and hawed for a long time about what would be on them, and we knew that whatever it was, it wasn’t going to be fight scenes or full-figure superheroes. After drawing the first issue I thought, “Perhaps we could have the smiley face on the cover,” and drawing it and immediately having a really good idea of where the series was going, another six cover designs popped into my head. I think the fact that what we sent to DC wasn’t, “Here’s this smiley face, the cover of the first issue,” but six or seven covers that all worked as bits of graphic design, was what really sold them on it. Subsequently, it was Alan’s idea to take it a bit further and make each cover the first panel of the story, and that's a really strong idea as well. The way that we rationalize it to ourselves is that it's a crossover. The cover of the Watchmen is in the real world and looks quite real, but it’s starting to turn into a comic book, a portal to another dimension. This is the kind of thing we think about while we’re doing it.

MOORE: Watchmen has just got to be more and more hard labor as it’s gone on. We started out with all these innocent ideas like making the smiley badge on the cover of the first one the first panel of the story, and then to be really clever we’ll make it the last panel of the story as well, and have it on the last panel of the book. Then we did that with the statue in the second issue as well, and by that time it's a feature and you’ve got to do it every issue. Then there’s the little quotes at the end of the episodes that didn’t get into the first three issues, but now they’re running OK and tying the whole story in with a quote. That seemed really clever and stylish and smart and sophisticated, but by the time you get to issue #8, you’re thinking, “Christ …” It’s like all those titles beginning with “V” [in V for Vendetta] and you make a rod for your own back sometimes. The story’s just gone on getting more and more complex.

MOORE: Watchmen has just got to be more and more hard labor as it’s gone on. We started out with all these innocent ideas like making the smiley badge on the cover of the first one the first panel of the story, and then to be really clever we’ll make it the last panel of the story as well, and have it on the last panel of the book. Then we did that with the statue in the second issue as well, and by that time it's a feature and you’ve got to do it every issue. Then there’s the little quotes at the end of the episodes that didn’t get into the first three issues, but now they’re running OK and tying the whole story in with a quote. That seemed really clever and stylish and smart and sophisticated, but by the time you get to issue #8, you’re thinking, “Christ …” It’s like all those titles beginning with “V” [in V for Vendetta] and you make a rod for your own back sometimes. The story’s just gone on getting more and more complex.

GIBBONS: This might come up when you’re asking questions later, but it’s where we really ought to have the Twilight Zone theme in the background because there’ve been some really spooky coincidences. For example, the issue that’s just out, #5, is about symmetry and there’s a scene in it where the two detectives we feature are called to this apartment where an aging hippie … [looks at Alan; laughter from the audience] ... has just butchered his children rather than have them killed in a nuclear war. Alan, as he usually does, made lots of suggestions for the decor of the apartment and I thought, “What they really need is a ’60s rock poster,” and I don’t know anything about ’60s rock groups …

MOORE: [Disbelieving] Oh ho ho.

GIBBONS: Well, I know lots about ’50s rock groups. I thought that it could be a Grateful Dead poster, because that ties in as these kids are dead, and they ought to be grateful … [laughter from the audience] … so I’d like to stress that not possessing any Grateful Dead albums, I got a book called The Album Cover Album and looked up Grateful Dead in the index for a cover, and it’s an album called Aoxomoxoa, which is a symmetrical word.

MOORE: It’s a Rick Griffin cover as well, which is absolutely symmetrical.

GIBBONS: And it’s got a skull on it, and throughout issue #5, there’s the skull and crossbones of the pirate ship. Also, this skull has an egg in its hands, and the book starts with Rorschach breaking an egg. And also on the facing page of the book there’s an album called Tales of the Rum Runners and I forget who it’s by but at the beginning of issue #5 we have the Rumrunner Club. [Tales of the Rum Runners is by Robert Hunter, with the cover also designed by Rick Griffin.]

GAIMAN: John Higgins wasn’t able to make it to the panel, so I thought it might be nice for Alan and Dave to comment on the coloring, which is rather unlike anything else ever seen before.

GIBBONS: It was my idea to use John because I’ve always liked the really unusual way that he does color, and I was struck coincidentally enough by a story he colored that Steve Dillon drew and Alan wrote, an ABC Warriors story [in the 1985 2000 AD Annual]. I thought it was such good work and not only did I really admire the color, the great thing is that he only lives about eight miles from me, which means that we can actually discuss it and have some kind of human contact rather than just sending it across the ocean. I couldn’t be happier with the way it’s colored. I could be happier with the way it’s printed, and I think what with the success of Dark Knight if DC had their chance again, they’d make it a full-color book like Dark Knight, but within the restrictions that he’s given I think John does some really startling stuff.

MOORE: I’ve always loved John’s coloring, but always associated him with being an airbrush colorist, and frankly I don’t like airbrush: it’s just lacquer. It looks to me to be too smooth; even though I can see there’s a lot of artistry and skill involved in doing it, it’s a bit plastic. So although I liked John’s coloring, I didn’t think airbrush would be right for this, and so Dave put that to John and he said, “No, I’ll do this in European-style flat color,” and he showed me the samples and they were wonderful. He just has different coloring ideas. I know that a lot of people don’t seem to recognize the amount of work a colorist does. That has been changing recently what with people like Lynn Varley, who are obviously really wonderful colorists, and John is in that category as well. In most comics the colorist will say, “Okay, here’s Superman — his cloak’s red, his costume’s blue, and his boots are red,” and he’ll go through the whole issue first and colors Superman’s costume making sure that it’s the same color the whole way through. What John does is go through and say, “OK, this is Rorschach — his coat’s a sort of off-brown, but if he’s in a bar and there’s red lights in the bar, it’s going to be a different color. If he’s out in the street and there’s sodium lamps or just moonlight, it’s going to be a different color,” and so the color of the characters’ costumes change according to what lighting they’re in, which is much more emotional and much more atmospheric than very straight plastic color all the way through. I’m knocked out with what John’s done, and some of the scenes have really come alive with color. We’ve thought about it when I’ve been doing the scripts and Dave has been dong the artwork, and we know that John’s going to do a real good job with it and plan around it to a certain degree, thinking, “That’ll look good, that’ll look nice,” like Dr. Manhattan on Mars, blue on pink.

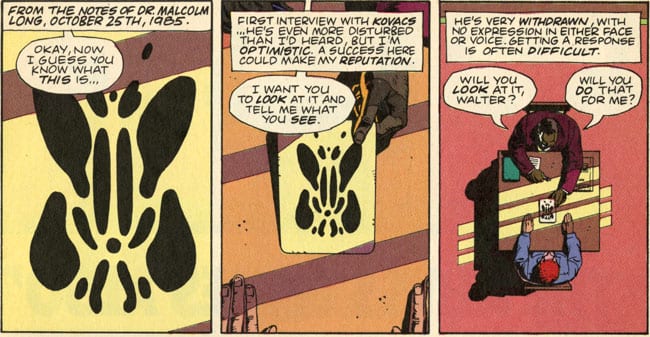

Something that’s really good about John as a colorist concerns issue #6: It’s the Rorschach story, and it’s really depressing. Lock the razor blades away before you read this one. The cover is a Rorschach blot, a card from the psychology tests just lying on a table, a pretty simple cover. John colored the cover and colored it really warm and cheerful, and it looks really nice. And Dave was saying, “Look, this is a bit of a bleak issue. Why have you colored it warm and cheerful?” And [John] said, “Well, that’s my plan. It starts off really warm and cheerful, so you color them that way, and on page five we make it a bit darker, and on page seven darker still, and it’s like the lights are going down the entire issue, so when you get to the end it’s really dark and really black.” Emotionally, John is using the colors to really take the readers down, which is really clever. That’s the kind of thinking that we’re trying to do with the art and the story, and it’s real nice that John is trying to put the same thing through with the coloring.

GAIMAN: Let’s throw it open for some questions.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: In Alan’s interview in Q Magazine there was a quote pertaining to Swamp Thing saying that if ever a country needed scaring it’s America. Do you feel Watchmen is taking this further?

MOORE: Yes. This is not anti-Americanism, it’s anti-Reaganism, and these are only personal opinions, not necessarily shared by Dave or John. My personal feelings, because I’m the writer and can do anything that I want, is that at the moment a certain part of Reagan’s America isn’t scared. They think they’re invulnerable. There’s this incredible up mood that leads at its worst excesses to things like the Libyan bombing and things like that, and they worry me and frighten me. The power elite in America and an awful lot of the people who vote for them seem to have this … I think the best example is a quote that Clive Barker dredged up for one of his books, The Damnation Game, from an explorer called Freya Stark, a wonderful old woman who went everywhere in the world, an incredible pioneer, and she wrote an awful lot of travel books and said some really bright things, and one of the things she said is, “The society that knows fear is not the society that’s faced with extinction. It is the society that has forgotten fear that is faced with extinction.” The society that just thinks that they can do whatever they want because they’re invulnerable, they’re not afraid, and they can gloss over the terror of the nuclear stockpiles, the world situation and all that and just think, “Hey, we’re doing all right, we’re OK.”

That’s unhealthy. I know it’s only a tiny little comic book that goes over there every month and gets seen by a relatively small number of people, many of whom perhaps agree with us anyway, so it’s difficult to see what it’s doing, but I was consciously trying to do something that would make people feel uneasy. In issue #3 I wanted to communicate that feeling of “When’s it going to happen?” Everyone felt it. You hear a plane going overhead really loudly, and just for a second before you realize it’s a plane you look up. I’m sure that everybody in this room’s done that at least once. It’s something over everybody’s head, but nobody talks about it. At the risk of doing a depressing comic book we thought that it would be nice to try and … yeah, try and scare a little bit so that people would just stop and think about their country and their politics. It’s not that America’s worse than England, that we’re any better than them, because we have our fair share of strange political leaders as well. When I’m doing V for Vendetta it’s aimed at England, and Watchmen is aimed at an American audience and the intention was to try and make people feel a little bit uneasy about it.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: To what extent have you had to fit into an American mode?

MOORE: It affects both of us. Dave is drawing for Americans and I’m writing for Americans. I was anticipating an awful lot of trouble when I started doing Swamp Thing, which is supposedly set in real America, just getting things wrong. You see how some American writers have handled England with the little thatched cottages in Charing Cross and things like that and you think you’re probably going to do the same thing over there, and it’s worrying. When we got into it I found that because Britain’s probably a cultural satellite of America anyway, I’d absorbed so much American TV, movies and records, books and comics that you tend to know the speech patterns. I still make mistakes, but you tend to have a feel for American speech patterns and stuff like that. With Watchmen we’ve got a little bit more leeway, particularly with the art, because it is a parallel world.

GIBBONS: I think that one of the mistakes I’ve made in the past is to switch into the American mode. Certainly the Green Lantern stuff that I did was “Let’s draw an American comic book,” but what I’ve actually done with Watchmen is to switch into the Dave Gibbons mode, and that’s the most successful way to do it. I do view America as an exotic culture, an exotic, far-off country, and I think that’s the approach to take, and because of the perspective you’re probably getting more to the reality of America than if you actually live there.

MOORE: I think by the fact that Dave’s changed some bits about the American landscape, like electric cars, slightly different buildings, everyone’s wearing double-breasted suits, there’s little spark hydrants for recharging your cars instead of fire hydrants, it perhaps gives the American readership a chance in some ways to see their own culture as an outsider would. There are enough elements of difference. When Americans read American comic books that show the American landscape, they tend to blot out the backgrounds, because it’s familiar to them, they don’t need to pay any attention, whereas in Watchmen I think people are being drawn into it and looking at the panels closely because it’s obvious that we are putting lots of little details in the background. With a bit of luck it will help to get across that feeling of an alien culture to an audience who lives there, which is what we want.

GIBBONS: That’s a really liberating thing to be able to say that it isn’t this world, because I don’t have to get a load of reference books out and get bogged down in reference. I can give it the feeling of America without having to draw a certain model of car, or a certain building or a certain place. I draw the Chrysler building, the sort of art deco thing, and by putting that in it just gives it that tie into reality to make it convincing.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: I’ve heard a rumor that Watchmen has been optioned as a film and a screenplay’s been prepared.

MOORE: The screenplay’s not been prepared, but the rumor’s absolutely true — it has been optioned for film, and it’s looking good. It was a substantial amount of money that was offered for the screen rights. We all know that a Silver Surfer movie has been being made for the past 20 years at least, so a lot of films get optioned, and I can’t promise that it will ever get made, but everyone seems very eager with the project. It’s not Walter Hill, and I don’t know where this Walter Hill story came from. I think it’s probably because 48 Hours was directed by Walter Hill and produced by Larry Gordon and Joel Silver, and it’s Larry Gordon and Joel Silver who want to do it. I spoke to Joel Silver on the phone, and he seemed like a real nice bloke. He was saying that he wants me to write the screenplay, starting next year maybe, and he also said, “Can you do it panel by panel like the comic book?” which I don’t think will be possible because that would make a real crap movie. It was written to be a comic, not a movie, and they’re not interchangeable, but the fact that he wants it done like that speaks volumes to me. They’re not going to give Rorschach a friendly waggy-tailed dog. Although that might be a good idea, mightn’t it? [Laughter.]

GIBBONS: As I remember, that’s one of my ideas! Blot the Dog. [More laughter.]

MOORE: So it looks good. I don’t know when it’ll be made or if it’ll be made, but the signs look healthy that it might be a good film.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: Do you actually own Watchmen?

MOORE: My understanding is that when Watchmen is finished and DC have not used the characters for a year, they’re ours.

GIBBONS: They pay us a substantial amount of money. ..

MOORE: … to retain the rights. So basically they’re not ours, but if DC is working with the characters in our interests then they might as well be. On the other hand, if the characters have outlived their natural life span and DC doesn’t want to do anything with them, then after a year we’ve got them and we can do what we want with them, which I’m perfectly happy with.

GIBBONS: What would be horrendous, and DC could legally do it, would be to have Rorschach crossing over with Batman or something like that, but I’ve got enough faith in them that I don’t think that they’d do that. I think because of the unique team they couldn’t get anybody else to take it over to do Watchmen II or anything else like that, and we’ve certainly got no plans to do Watchmen II.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: Is it possible to handle the superheroes realistically without the fascist overtones creeping in?

MOORE: I think that when Watchmen was first announced everybody assumed that it was going to be Squadron Supreme, the superheroes take over. We never said that. We said that we were going to try to treat them realistically. I think that because there’ve been a lot of fascist overtones in Marvelman [Miracleman] people assumed that the superheroes had taken over. There aren’t really any fascist superheroes in Watchmen. Rorschach’s not a fascist; he’s a nutcase. The Comedian’s not a fascist’ he’s a psychopath. Dr. Manhattan’s not a fascist; he’s a space cadet. They’re not fascists. They’re not in control of their world. Dr. Manhattan’s not even in control of the world —he doesn’t care about the world. I think that while people expected that, we’ve not investigated the idea of superheroes as fascists the same way that Frank [Miller] has in Dark Knight, or the same thing they’ve done in Squadron Supreme. It wasn’t really our intention. Our intention was to show how superheroes could deform the world just by being there, not that they’d have to take it over, just their presence there would make the difference. It’s what we try to show in Watchmen #4. From the point where Dr. Manhattan appears, it slowly starts to go downhill from there — everything starts to change. He doesn’t take over the country or make people subservient to him, but just his presence there makes everything begin to change. Yet on another level, if you equate Dr. Manhattan with the atom bomb, the atom bomb doesn’t take over the world, but by being there it changes everything. That was more the idea that I was trying to explore. I’d say it’s possible to do superhero stories that are realistic without getting into that Nazi mode.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: Is the Black Freighter anything to do with Bertolt Brecht?

MOORE: It certainly is, you clever cultured boy. For those cultureless people in the audience, Bertolt Brecht, Bert as I call him, wrote The Threepenny Opera with Kurt Weill. It’s a magnificent story set around the coronation of King Edward in England. It’s where the song “Mack the Knife” comes from, and it was originally a very nasty bloody song, whatever Bobby Darin did with it. One of the prostitutes in the story, a girl called Jenny, sings a song called “Pirate Jenny.” She works in a hotel, scrubbing floors, and in her head she’s thinking about all these guys smoking cigars who’re sneering at her, and there’s a black freighter waiting out at sea and one day it’s going to come into town with guns firing from its bow, and the pirates are going to teem off the ship and run through the town, and they’re going to be piling up the bodies. It’s this horrible black vision of this ship coming in with a skull on its masthead. Everything’s still in the town, with everyone wondering what’s going to happen, and then this prostitute says, “I step out, looking pretty in the morning with a ribbon in my hair, and a cheer splits the air.” In her dream, she’s the pirate queen, and they’re going to kill all the rich people and they’re going to say to her, “Shall we kill them now or later?” and she’ll say, “Kill them now.” At the end she goes out on the Black Freighter. It’s such a powerful image, this death ship coming in, and in the Watchmen another sort of death ship is coming in — the nuclear war that’s looming. The idea of death that you can do nothing about just coming in on the tide just seemed to tie in so nicely that I thought, “I’ll rip that off. I’ll take the ‘Black Freighter’ and bring it into the Watchmen as one of the pirate comics,” using it as a counterpoint.

GAIMAN: Anything from Dave on the pirates and the “Black Freighter”?

GIBBONS: I’ve never heard of it.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: How did you actually conceive and put together the universe of the Watchmen? And question two is “Who watches the Watchmen”?

GIBBONS: As Alan said, it’s a universal world that’s deformed by the presence of superheroes, and I think Alan is more concerned with the social implications of that and I’ve gotten involved in the technical implications of it. You’ve got electric cars and airships because of the technological breakthrough. Dr. Manhattan could transmute metals and create supplies of rare metals and so there probably wouldn’t be as much need for the petrochemical industry because you’d have clean electric cars. I’m not putting this very well. They can’t make electric cars here because the batteries are too heavy, and there’s a thing called polyacetyline something, but you need lithium to make this, and lithium is a very rare metal. Of course, Dr. Manhattan can actually form lithium, so there’s as much lithium as you want, so that’s why you’ve got electric cars.

GAIMAN: What about the cigarettes?

GIBBONS: They were just to give a small element of strangeness. It’s something they obviously smoke, but doesn’t look like anything people here smoke.

MOORE: It’s like a water-cooled pipe or something like that, something to cool the smoke. It’s a slightly different sort of cigarette, and there’s the Gunga Diners. It was Dave’s idea to have Indian restaurants instead of McDonalds, and that made sense because there’s a different political situation in this world, there’s going to be wars in different places. In our story, some sort of conflict in Asia has caused a massive famine in India, so there’s been a massive amount of Indian and Asian refugees teeming into America, and consequently you’ve got Indian food catching on, and you’ve got this stream of Gunga Diners stretching across the country. There’s lot of little things like that and all of them are semi-logical, they all follow from the idea of superheroes. The comics are different because people are fed up with superheroes, there wasn’t a big superhero boom like there has been here, and so all the little details are worked in. That’s how we came up with the world. We took a central premise and worked it from there. As for “Who watches the Watchmen?” we didn’t know were the quote came from until I had a phone call from Harlan Ellison, who phoned up just to tell me because he’d seen us expressing our ignorance in Amazing Heroes, and wanted to put us out of our misery. Apparently the original quote is “Quis custodiet custodies?” which means “who guards the guardians,” “who watches the watchmen,” and it was said originally by the satirist Juvenal, and it was the quote that got him slung out of Rome and placed in exile. It’s a dangerous political quote. Who’s watching the people who’re watching after us? In the context of Watchmen, that fits. “They’re watching out for us, who’s watching out for them?” That’s where the title comes from. It’s also a nice bit of graffiti, so you get little snatches of it in the background.

MOORE: It’s like a water-cooled pipe or something like that, something to cool the smoke. It’s a slightly different sort of cigarette, and there’s the Gunga Diners. It was Dave’s idea to have Indian restaurants instead of McDonalds, and that made sense because there’s a different political situation in this world, there’s going to be wars in different places. In our story, some sort of conflict in Asia has caused a massive famine in India, so there’s been a massive amount of Indian and Asian refugees teeming into America, and consequently you’ve got Indian food catching on, and you’ve got this stream of Gunga Diners stretching across the country. There’s lot of little things like that and all of them are semi-logical, they all follow from the idea of superheroes. The comics are different because people are fed up with superheroes, there wasn’t a big superhero boom like there has been here, and so all the little details are worked in. That’s how we came up with the world. We took a central premise and worked it from there. As for “Who watches the Watchmen?” we didn’t know were the quote came from until I had a phone call from Harlan Ellison, who phoned up just to tell me because he’d seen us expressing our ignorance in Amazing Heroes, and wanted to put us out of our misery. Apparently the original quote is “Quis custodiet custodies?” which means “who guards the guardians,” “who watches the watchmen,” and it was said originally by the satirist Juvenal, and it was the quote that got him slung out of Rome and placed in exile. It’s a dangerous political quote. Who’s watching the people who’re watching after us? In the context of Watchmen, that fits. “They’re watching out for us, who’s watching out for them?” That’s where the title comes from. It’s also a nice bit of graffiti, so you get little snatches of it in the background.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: What’s the quote for the third comic?

MOORE: It’s “Shall not the judge of all the Earth do right?” The quote from issue #l’s “At midnight all the agents” is from a Bob Dylan song: “At midnight all the agents and the super-human crew go out and round up everyone who knows more than they do,” from Desolation Row, which fits in pretty nicely with the first issue. The second one is “Absent friends” from The Comedians by Elvis Costello: “I should be drinking a toast to absent friends instead of these comedians,” which with the second issue being about the Comedian fits in nicely. The third one is from the Bible and it’s from that bit in Genesis where God’s going to nuke Sodom and Gomorrah, and one of the prophets goes out and tries to barter with him and says, “If there’s a couple of good people there perhaps you could spare it,” and God says, “Yeah, all right,” so he says, “What if there’s one good person there? Is it OK?” and God says, “Shall not the judge of all the Earth do right?,” so that also fits in nicely. It fit in very nicely with the story because there’s an awful lot of judges of the Earth there: the news vendor who is giving his judgment of the Earth earlier on, the President and the people in the war room at the Pentagon who’re obviously judges of the Earth in a very real sense, because they’re the ones who’re going to decide when to set the nukes flying and there’s Dr. Manhattan. At the end with that last panel where he’s sitting there on Mars looking up at the sky it should have said, “Shall not the judge of all the Earth do right?” So that’s where that one comes from. The rest of the issues will all have the proper quote at the end.

GAIMAN: Which comes first for you, the quote and the title or writing the episode?

MOORE: What we do is think of the actual story and what’s in it and then try and come up with a quote that’s appropriate, and then when we’ve got the appropriate quote I write the script, and write in lots more bits that are appropriate to the quote to bring it more into the center of the story.

FROM THE AUDIENCE: Is there any chance of turning Under the Hood into a book?

MOORE: No, because there’s only three chapters of it: it’s not a real book you see.

GIBBONS: Ooohhh.

MOORE: If you opened it up, most of the pages are blank. Originally we thought, “OK, we’ve got 28 pages of comic strip in here and what are we going to do with the rest of them? We thought “letters page. But there’s no letters coming until issue #3, so what shall we do to fill the first three issues? Shall we do something self-congratulatory that tells all the readers how wonderful and clever we all are for thinking up all that?” And we thought, “No, because that should be obvious, shouldn’t it?” So we thought we’d do something that tied in with the story and threw this Under the Hood stuff in because it was mentioned in the book. By the time we got around to issue #3, #4, and so on, we thought that the book looked nice without a letters page. It looks less like a comic book, so we stuck with it.

All images written by Alan Moore, drawn by Dave Gibbons and colored by John Higgens. ©DC Comics