For more than a decade, Jeffrey Lewis has served as one of New York’s brightest singer-songwriters. His work walks the thin line dividing folk and punk, often falling into the latter camp during its quietest moments. The perceived insouciance of his delivery and playing—songs can seem held together by expired Scotch Tape—masks the deliberateness of their creation. He is a first-take kind of guy; the hours other musicians might lose to practice are here devoted to artistic scheming. The music reeks of New York City, being wordy, funny, casually learned, and, of course, proudly neurotic.

For more than a decade, Jeffrey Lewis has served as one of New York’s brightest singer-songwriters. His work walks the thin line dividing folk and punk, often falling into the latter camp during its quietest moments. The perceived insouciance of his delivery and playing—songs can seem held together by expired Scotch Tape—masks the deliberateness of their creation. He is a first-take kind of guy; the hours other musicians might lose to practice are here devoted to artistic scheming. The music reeks of New York City, being wordy, funny, casually learned, and, of course, proudly neurotic.

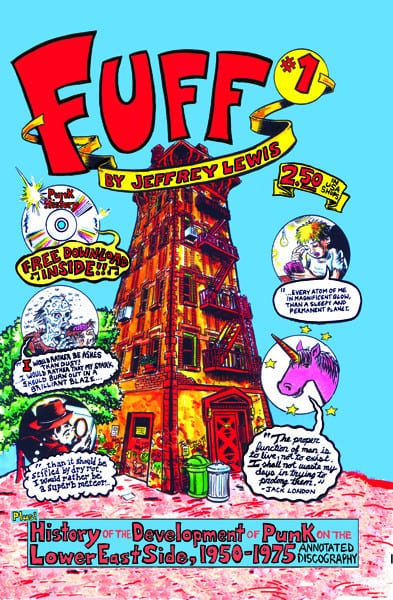

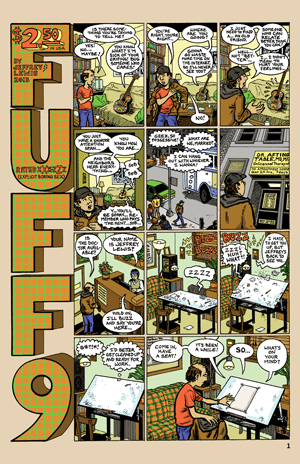

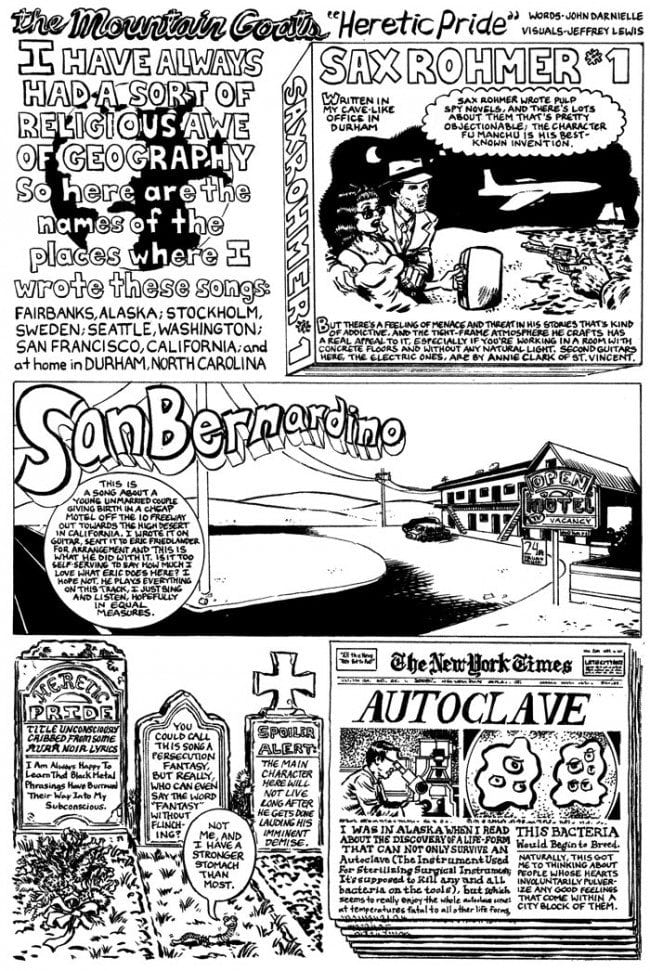

Concurrent to his music career, with equal passion and perhaps greater technical acumen, Lewis has pursued comics. At times, the singer’s visual art comes tied to his music. He designs extravagant album covers and liner-notes, generally for himself and occasionally for peers. In concert, for certain songs, Lewis will exchange his guitar for a large, battered sketchbook, accompanying his lyrics with crayon-and-marker illustrations. Yet the bulk of Lewis’s life in comics is far removed from stage or record. For 18 years, he has been sporadically working on a book about Watchmen. Most significantly, since 2004, Lewis has published Fuff (né Guff), a floppy comic book that recently reached issue #10. Fuff is crafted in the variety show mold, with issues including travelogues, superhero spoofs, and self-deprecating sex memoirs, among other things. (Best is “Stories My Dad Tells,” a recurring feature in which Lewis’s father narrates loopy tales of the 1960s.) All pieces are written and drawn by Lewis, who applies the exacting grace of somebody who spent too much time in his bedroom during adolescent.

Lewis, 39, lives in the East Village, in the same apartment complex where he grew up. (His parents are a block away.) When not on tour, he hosts a weekly art gathering in his living room, inviting comic makers both budding and celebrated to draw, eat pretzels, and chew the fat. The nights have a communal spirit familiar from the host’s musical performances—the cult singer with an open door. Lewis met for an interview in the apartment, which is strewn with the comics, records and other cultural detritus that someday, no doubt, will topple over and entomb him.

Jay Ruttenberg: I interviewed you a couple of times when I was a music critic in the ’00s. But I actually knew of you through a mutual friend when we were in college in the mid-’90s. Back then, I thought you were a comics guy, not a music guy.

Jeffrey Lewis: Well I was doing comics all my life—in ’96, I would not have been considered a music guy at all. I didn’t even start writing songs until I was out of college. My entire life up until that point was that I was gonna draw comics. That was the path I was on. I graduated college in ’97 and spent the summer in Maine working on comic book stuff. I came back home and was living in an apartment on West 28th Street. The rent was almost nothing. I was just living off day-old bagels and drawing comics all day and all night.

Is that when you started performing music?

I had so much time to kill. I had just graduated and didn’t have that many friends in the city. I started playing a little more guitar and making up some songs in the same bedroom where I was drawing comics. I started playing my songs at the open mike at Sidewalk. I had been going to Washington Square Park and selling my self-produced comics. Playing at Sidewalk was an extension of what I was doing at Washington Square Park—a way to sell my comics. I could get up onstage, play a couple songs and say, “By the way, I have comics for sale.”

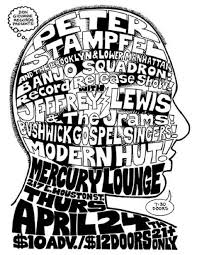

You were also drawing really elaborate comic-book show flyers.

I always joked that I would play gigs to advertise the flyers, rather than the other way around. Here’s one—it’s like a gum-comic thing.

My God, it’s your own Bazooka Joe!

Look, there’s even some nasty old gum from 1998. You know, in the late ’90s, Chris Ware was like a god. It was the idea of exploding the form, cause every issue of Acme Novelty was a new size. It was such a delight to go to a comic store and see what he would do that was totally out of the box. So that’s what I was doing with flyers like this.

You found an audience for your music fairly quickly, right?

I had been making the rounds with my comic books, doing the rejection letter thing. Meanwhile, while I was getting rejection letters for my comic books, I was getting more and more acceptance for the music and ended up with Rough Trade Records signing me. It was this incredible, bizarre thing to happen. I had never sent my music to record labels or to clubs the way I was sending my comics and getting rejection letters! With music, everybody was coming to me. Bands started asking me to go on tour with them. I was like, “This is great. I don’t have to get a day job—this will be great for drawing my comics.”

And how’d that work out?

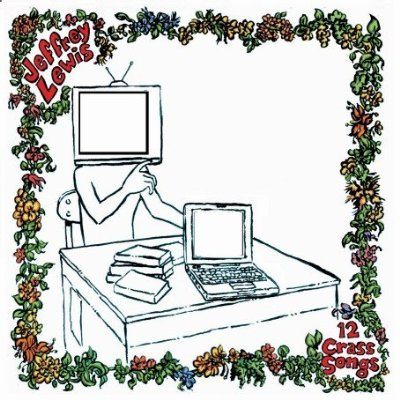

It didn’t! The amount of time it takes to book concerts and all that stuff is all-consuming. So I probably draw less comics than ever. But I just managed to do two more issues of Fuff. And my album packaging is always some kind of elaborate design. Look at this packaging [2007’s 12 Crass Songs CD]—I should have won a Grammy! See, there’s a disconnect between the realms. When the label sends out the CD to reviewers, it’s in some blank slipcase. So none of the reviewers know that I put more time into the packaging than I put into the recording.

When you started, how much of a lark was music?

When you started, how much of a lark was music?

It was not a career goal at all. Which is not to say that I didn’t think the songs were really good. I knew I couldn’t sing and I knew I couldn’t play. But I also knew that I was expressing things in a way that affected me and felt powerful to me. And in some ways, it was a comic-book aesthetic. Joe Matt’s Peepshow comic was as much an influence on my songs as any songwriter.

How so?

Just the idea of, Okay, your life is crap. But if you can express that, it’s so funny. It’s just a way to turn tragedy—all of your loneliness and terrible habits—into comedy. Today that’s a bit of a cliché. Oh great, another confessional comic or songwriter—spare me. But at that time, it was a revelation to me. And it fed into my songs, which are more influenced by Joe Matt and Chester Brown than by Bob Dylan or what-have-you. There’s a huge amount of comic-book stuff in my head that feeds into the way I think of language and pacing in the songwriting.

You mentioned playing music to draw attention to your flyers. Obviously, that’s a stretch, but I imagine there’s a degree of truth to it. You still sell a great percentage of your comics at your merch table.

There’s no outlet to reach people. And I was sort of trapped—in some ways, I still am—between the zine self-publishing world and the comic-book world. I’m a little too pro for zines or mini comics. My comics are regular floppies, with the glossy cover. I’m a little too much like a normal comic to fit in.

There’s nothing punk rock about it. It’s not outsider art but it’s not insidery, either. Basically, I’m a regular comic artist who’s just not good enough. What’s interesting is that that’s what I see in a lot of my musician friends. They were going to be the Grateful Dead or Elvis Costello. And when your aims are that high, no matter how good you are, you’re just a second- or third-rate version of that. Whereas when I started making music, I had no high aspirations. I was an actual, first-rate version of me. I went out there with full authority—this is how I sing, this is how I play, these are the kinds of songs that I can write. Not overreaching, but actually nailing it. I was able to put that forward musically because I had no illusions of being any better than myself. Whereas with my comics, I had all these illusions.

So your fear is that in comics, you’re the equivalent of some Berklee College of Music guy, slap-bassing?

To some degree. David Heatley, whose work I love, was telling me that when he sees a comic that looks like somebody trying too hard, it turns him off. In some ways I feel like Chris Ware is to blame for that huge simplification. Suddenly, Moebius was not an influence; Charles Schulz became the ideal. You have this greater simplification, which was like a punk-rock aesthetic. I’ve been doing the comic-book night at my apartment every week for years. The younger people—who are like 21, 22, 23—are almost all women, which is a really interesting shift. Punk rock opened the gates to a much more equal gender representation in rock. I think that’s what’s happened to comics since the early 2000s. There’s the same removal of a high-level of technique—that heavy-metal, “I’m gonna stay in my bedroom because girls don’t talk to me and learn how to shred.” The stereotypical sexual frustration that leads to the higher levels of technique was removed from comics the way it had been removed from rock & roll by the punk movement. So now you have this much wider gender representation in people making underground and alternative comics. In a lot of these comics, the story and personality are much more important than three-point perspective. But I can’t let go of three-point perspective! The same way that my friends who play music, since they know how to play the fancy slap-bass, can’t not do it.

Punk rock comes along and you’re like—

Jethro Tull in 1978. You can’t make a Ramones record.

At the same time, the flipbooks that you draw for your illustrated songs are much cruder than what you do in Fuff.

In some ways, it’s a dumbed down version of my comics. The art is so simple, cause it has to be seen from the back of Bowery Ballroom.

When did you start introducing drawings onstage?

In my early musical gigs, I was constantly trying to make every show completely different. I was so lucky that nobody was paying attention—I had so many embarrassing failures. I’d dress up in a red-hooded sweatshirt with goggles and do this fake Devo thing, where I’d be playing keyboard with one hand and guitar with the other. I did stuff with pre-recorded tapes. The illustrated songs came out of that. I thought it would be funny. Somebody would request a song and instead of playing it, I would show a drawing version of it. It was a one-off.

And look at your illustration book now—it’s like Woody Guthrie’s guitar.

I realized that there were certain songs that didn’t work very well as songs. But when I did them as illustrated things, they just killed. They stuck. And then…well, a number of times in my life, I’ll get an idea that I just know is going to be great. I’ll start laughing out loud walking down the street, having a manic breakdown, where I can feel my brain, like, slipping down the edge of insanity. And I remember walking on a dirt road in Maine when it dawned on me that with the illustrated songs, I could do the history of things. I could do the history of Rough Trade Records. The history of the Fall. And then after doing a couple of music ones, I was like, I can do the history of communism! It’s limitless! I can do anything!

The illustrated songs meld your music and comics. But there’s a lot of overlap between those realms, in general.

They’re people’s art forms. The thing that connects everything I do—folk music, comic books, and punk music—is that these are three forms that are cheap and simple. You can do all of them at Occupy Wall Street. They’re not jazz, ballet, or classical. They’re not even classic rock.

It’s self-taught art, made by people who graduated from college.

Punk doesn’t mean a drunk skinhead shouting shit. To me, it’s music that has a core that’s very smart and a surface that’s stupid enough that only a smart person will realize how smart it is. It’s crude music that’s made by people who are much smarter than the crudity implies.

How does that tie into the comics?

My comic books take for granted that comic books are a furshlugginer art form. That you can do great comics and it’s still under the mask of crude punk rock. Even if you’re the Hernandez Brothers or Dan Clowes—at the apex of artistic brilliance—the very fact that it’s a comic book means that, in the eyes of society, you’re a piece of crap. That’s the punk rock concept. Maybe that’s what happened in the ’90s and the early 2000s. People like Adrian Tomine and Chris Ware started doing covers of The New Yorker. Comic books becoming accepted meant that, in order for comic books to stay punk, they had to get punker. So for me, even if I can draw and write at a technical level, it’s still underground just because it’s a comic book. Whereas for these younger kids, if you draw as well as Gilbert Hernandez you’re no longer part of the underground, since comic books have more outreach into the mainstream than they used to.

Was the period in the ’90s, just before that mainstream exposure, a pinnacle?

In some ways, alternative comics of the ’90s were so good because the mainstream sucked so much at that time. Now, the mainstream has upped its game tremendously. The same way that in the ’80s, punk rockers could be like, “You couch potatoes—TV is crap, the real culture is out in the clubs.” Whereas now, a lot of the high-art culture has been happening in TV. It’s not like all these people are sitting at home watching Three’s Company while there’s a Sonic Youth show down the street. I feel the same with comic books. There was a period in the ’90s when all the trashy Rob Liefeld stuff had taken over the mainstream. The mainstream took a nosedive in the early ’90s right at the moment that Fantagraphics and all these things sprung up to take its place.

It was all very Northwest, like the music at the time.

I remember being in Seattle in ’93 or ’94 to see the Grateful Dead and thinking, Wow, this is the comic book mecca. Except alternative music kind of exploded by the mid-’90s. You started having all the Stone Temple Pilots and post-post-Nirvana stuff. Whereas comic books just kept bubbling under without the attention of the mainstream. In retrospect, it seems like a golden time. You would walk into the store and get that new issue of Eightball and it was just unbelievable. I was aware of the fact that somebody needed to draw as good as the Hernandez Brothers and write as good as Alan Moore. And when Eightball hit, especially the first issue of “David Boring,” the door opened. This was it. This was the moment. And then it was gone. The second issue of “David Boring” was great but not a leap forward, and then the third was a disappointment. And that was it. That was the end of Optic Nerve. Peepshow stopped coming out. None of those guys ever did anything. It was the end of that alternative boom of the ’90s.

This happened across cultures in the ’90s. You had a period of idealism with Clinton, but by the late ’90s money was everywhere and it led to the disaster of George Bush. A lot from the period went unrealized. Why do you think this happened? Was Generation X simply too small to compete with the Baby Boomers?

There are a lot of factors at play. I feel like the late ’90s was the absolute pinnacle of obscurest culture in the two minutes prior to the Internet. The kind of cultural recall that you found in Eightball, or the dark, dusty past of forgotten toys and forgotten design elements that was in Acme Novelty Library, or what Dr. Dre brought to hip-hop. When Dr. Dre is sampling Funkadelic in 1992, those records were only 20 years old. But they seemed to come from 100 years ago. It was like an excavation of a completely lost world. Or Yo La Tengo and the influences that they’re weaving together on Electr-O-Pura. When the Internet really hit around 2000, those skills of being the repository of the accumulated knowledge of those lost cultures, it was like a water balloon that spread a leak and left a pool of water everywhere.

Everybody knows the Feelies now—or at least can find out in ten seconds.

Right. My record collection—my pride, the years of searching that it took me to find every Love record, or every Country Joe and the Fish record…people don’t have the dust to dig through. It’s just there. What we have lost so irrevocably is lost culture.

We lost something by finding it.

Yes. Also, culture doesn’t move. I’m always thinking about the compression of time. The difference between the Rolling Stones in 1965 and 1985—that’s 20 years. That’s a band that started in 1995. Or in 1980, when we’re little kids, there’s rap music and Blondie on the radio. And Jimi Hendrix had only died ten years earlier! Hendrix’s first album had come out 13 years prior, which is the difference between now and 2002. If it was 1980 right now, Hendrix’s first album would have come out after the Twin Towers were destroyed. Here I am! I finally get the opportunity to do an interview about comics and I talk about music.