Bart Beaty and Benjamin Woo begin The Greatest Comic Book of All Time by acknowledging that fans love to make best-of lists. I instantly thought of pop music super-fan Rob in the novel and movie High Fidelity. He is constantly making lists, and the lists tend to be “top five” lists. The listing activity is always in service of naming the “greatest” of whatever is being listed. Beaty and Woo then discuss about several top 100 and top 500 lists from the world of comics, including Hero Illustrated (remember them? They were kind of a low-level Wizard knock-off) list, “The 100 Most Important Comics of All Time” from 1994 and The Comics Journal’s 1999 list “The Top 100 (English-Language) Comics of the Century” (note: both Bart Beaty and myself contributed to that list). The authors point out that Youngblood #1 by Rob Liefeld was on the Hero Illustrated list but not on The Comics Journal list. This book doesn’t express an opinion on whether Youngblood #1 deserved to be on either list. They write, “We have no intention of lecturing you about the comics that we think you should read. Rather, we want to examine the very process of list making and curating. We are not interested in what makes great works so great but how any work comes to be seen as great.”

The conceptual framework they use is “symbolic capital.” This is derived from the work of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. They write, “Any given work or creator will have differing levels of economics (i.e., sales), social (i.e., buzz and connections), and cultural (i.e., prestige) capital, but symbolic capital represents an overall index of social capital.” For the most part, Beaty and Woo only look at economic capital and cultural capital. They have somewhat quantifiable ways of looking at each. For economic capital, they can look at actual sales of the work of a given cartoonist or specific book. For cultural capital, they look at how often a cartoonist or book has been written about in peer-reviewed academic journals as recorded in the Modern Language Association International Bibliography or how often it has been listed in the Bonner Online-Bibliographie zur Comicforschung, which lists scholarly but not necessarily peer-reviewed articles, including those in The Comics Journal. They created a chart of four quadrants that any given comic book creator or work might fall in. The top spot is reserved for those that have high levels of both economic and cultural capital—that have sold well and are highly esteemed by scholars.

Obviously the quadrant to belong in is quadrant 1 if you want to be in the canon of great comics. But there are all kinds of complicating factors, and the book is an opportunity to examine these factors.

Needless to say, scholarly articles are not the only way to determine cultural capital, nor necessarily the best. They do have the advantage of being quantifiable, while other measures of prestige are harder to quantify. But one way to determine cultural capital would be in terms of mentions in the media. For example, the New York Times makes a tool called Chronicle available that counts how many times a certain phrase has been mentioned in articles in the Times. Google has a similar tool called Ngram, which uses Google’s database of 5.2 million books. We can posit mentions in books or in the New York Times—both of which are highly esteemed by the middle class educated people—would be reasonable measures of cultural capital. Whether they are better than peer reviewed scholarly articles is arguable, but Chronicle and Ngram both create quantifiable results, just as the MLA International Bibliography and Bonner Online-Bibliographie zur Comicforschung do.

Excluding chapter 1, the chapters are all titled in the form of a question. Chapter 1 is “What If the Greatest Comic Book of All Time Were…” The first chapter is “Maus by Art Spiegelman?” One thing oddly academic about these chapters is that each one features an “abstract” and a list of “keywords.” This presumably helps busy academic decide of they need to actually read the chapter in question. That said, the pair write in an easily accessible style and avoid heavy academic jargon. They start the Maus chapter by pointing out the prestigious award nominations Maus got (the National Book Critics Circle) and the awards it received (a Pulitzer). Both of these were unprecedented for a comic book—they elevated consideration of Maus to the same level of already consecrated genres like novels. And the authors remind us that Maus has had by far more academic writing about it than any other comic book or comic book author.

They write that “Spiegelman was able to appeal to both the literary- and art-world publics—and their respective institutions of legitimation [the Pulitzer and MOMA, for example]—an a way that no cartoonist had before and few since.” It also helps that Maus sold very well in multiple editions and formats. They write that the only comic that has come close to pushing Maus off its pedestal is Fun Home by Alison Bechdel.

The next chapter is “A Short Story by Robert Crumb?” They point to Crumb’s many problems in achieving high social capital. First, his works haven’t sold all that well (obviously many comics artists would envy Crumb’s sales, but compared to Maus and many other examples in this volume, Crumb’s sales are modest). But perhaps more importantly, from Beaty and Woo’s point of view, is that his work is a challenge for academics due to its misogyny and its trading in racial caricature. Additionally, there isn’t a single obvious work by Crumb that can be pointed to—a side-effect of the fact that Crumb’s work primarily in short stories instead of graphic novels. But in terms of cultural capital, Beaty and Woo point out that Crumb has had a successful career in the art world, achieving high auction prices for his original art and it having been shown in numerous museums. “More than any other American cartoonist, Crumb is positioned as an ‘Artist,’” they write. “He is consecrated in different ways and by different institutions than Spiegelman and the graphic novelists.”

Other chapters include “A Superhero Story by Jack Kirby?” (superhero comics don’t have much cultural capital), “Written by Alan Moore?” (the rise of the “quality popular comic book”), “The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James” (hobbled by low sales and obscurity), “By Rob Liefeld?” (which includes an amusing description of Wizard magazine as having an “editorial voice somewhere between Animal House and Revenge of the Nerds, interpellating a white, heterosexual male reader who loved fart jokes and Star Wars in equal measure.”), “An Archie Comics?” (low cultural capital, but very high sales in its heyday—much higher than those of Jack Kirby comics), “Not by a White Man?” (which in addition to the obvious, deals to a large extent with the rise in popularity of “young adult” comics by such creators Raina Telgemeir, Gene Luen Yang, and Mariko and Jillian Tamaki), “Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi?” (which deals with the question of “foreign capital”), “Dave Sim’s Cerebus?” (which talks abut bad timing and how the esteem of work like Cerebus could possibly be revived), and finally, “Hicksville by Dylan Horrocks?”, a graphic novel that covers many of the same issues of the social capital of comics as The Greatest Comic Book of All Times. Each possible “Greatest Comic Book of All Time” is given pros and cons in terms of popularity/sales and esteem (not just how beloved it is, but who loves it). And in almost every case, it is made clear that the choice of comic book or cartoonist they chose to consider is in some way a stand-in for many other possibilities (Art Spiegelman’s chapter could have been about Alison Bechdel, Alan Moore’s about Neil Gaiman, Archie comics about Dell or Disney).

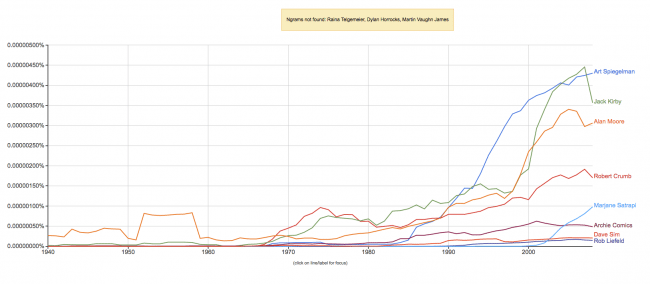

It seemed to me that it might be useful to look at these in terms of the Google Books Ngram Viewer, which as I said measures mentions in the books in Google Books’ database during the years you set. I used the following search terms:

Art Spiegelman

Robert Crumb

Jack Kirby

Alan Moore

Martin Vaughn-James

Rob Liefeld

Archie Comics

Raina Telgemeier

Marjane Satrapi

Dave Sim

Dylan Horrocks

In some cases we may be getting false positives (there have been other people named Jack Kirby and Alan Moore who were apparently written about in books before either of the two comics creators). Some have apparently not yet been written about in any of the books in Google’s database. If the Ngram can be used as a surrogate for social capital, it suggests that Spiegelman is number one, Kirby number two and Alan Moore number three.

(I would have liked to the same with the New York Times’ Chronicle, but I couldn’t find an easy way to export the data.)

Why should we care about this? For Beaty and Woo, the answer is obvious—they are both academics studying comics. Woo is an assistant professor at Carleton University and Beaty is a professor at the University of Calgary and author of several books on comics, including Unpopular Culture: Transforming European Comics in the 1990s, Comics Versus Art and Twelve-Cent Nancy. So counting peer-reviewed articles about comics may seem a natural activity to them. Also, it feels useful when there is no comics canon in the academic world to come up with some means of creating one that is more “objective” than just some guy’s opinion. Bourdieu provides the basic tools for such an evaluation.

But as you read The Greatest Comic Book of All Time, there is still a lot of subjective interpretation on the parts of the authors. They use data, but not exclusively. And many of their conclusions seem like little more than what an average educated observer would conclude without access to, say, Bonner Online-Bibliographie zur Comicforschung. I think anyone can agree that the oeuvre of Rob Liefeld and Martin Vaughn-James’ The Cage would both have low social capital for different reasons (a generally-held low opinion of Liefeld’s work among those who are familiar with it and the obscurity of Vaughn-James’ The Cage). The pleasure in reading The Greatest Comic Book of All Time lies not in the various data they’ve gathered, but in their interpretations of it.