Mike Dawson delivers an uneven collection of personal essay-style memoir comics, occasionally thoughtful, but often thoughtless in its concern for others. The stories, culled mostly from The Nib, Kickstarted to fund production, and now published by Tom Kaczynski’s Uncivilized Books, focus on parenting in a hyper-masculine, capitalist, culturally volatile age. While I enjoyed some elements of the book, many rattled me (I’ll get to those in a moment).

One comic essay has Dawson looking at his daughter's infatuation for a Disney princess show called Sofia the First. Dawson wonders: what does the show's implicit acceptance of a ruling class mean for his daughter, taking that in taking in these stories?

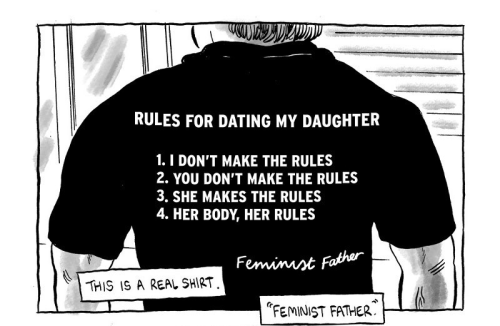

In the title piece, Dawson churns over the future, when his daughter will be a teenage girl, dating. He contrasts the traditional toxic masculinity-soaked "Rules for Dating My Daughter" tee-shirt/meme with the updated "Feminist Father" version. He then suggests down where they both go wrong—with implied ownership over a daughter's mind. Over the course of the stories, Dawson lets go of many preconceptions, often painfully.

The rendering loosens up from the fussiness that sometimes plagued Dawson's drawings in earlier works, such as the funny and bleak coming-of-age graphic novel, Troop 142. Both narratively and visually, the short format seems to agree with him. A recursive, playful quality comes from banging different drawing styles against each other. Cartoony, ink-wash drawings sit alongside hatch-heavy pages, giving different weights to respective moments.

The rendering loosens up from the fussiness that sometimes plagued Dawson's drawings in earlier works, such as the funny and bleak coming-of-age graphic novel, Troop 142. Both narratively and visually, the short format seems to agree with him. A recursive, playful quality comes from banging different drawing styles against each other. Cartoony, ink-wash drawings sit alongside hatch-heavy pages, giving different weights to respective moments.

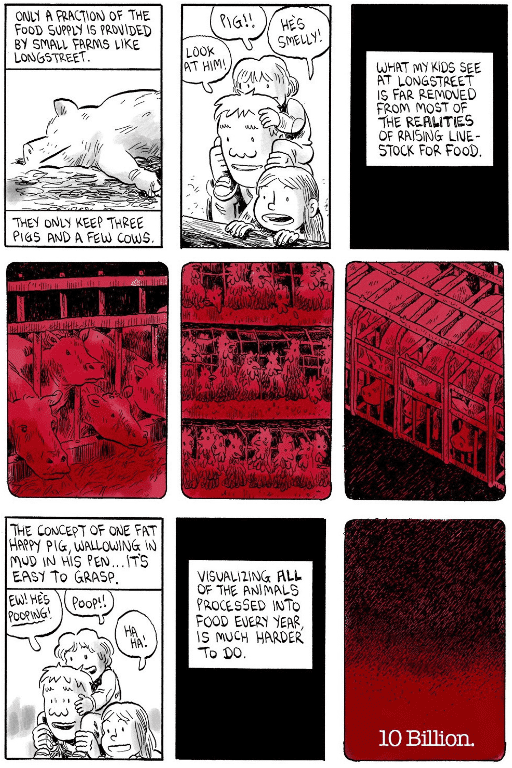

In "Longstreet Farm," Dawson takes his kids to the titular old-style farm, much like the serene Terhune Orchards I visited as a kid, also in suburban New Jersey. Dawson wrestles with the disconnect between this idealized farm that his kids see, and the factory farming that produces the actual meat that the kids are eating for dinner. Dawson plays with three visual levels here: black and white ink wash for their visit to the farm, bright colored coloring book-style drawings of animals, and visions of factory farms in harsh blood red. (This strip was actually an instrumental factor for me deciding to try going vegetarian again, after going back to eating meat for a couple of years.)

In "Longstreet Farm," Dawson takes his kids to the titular old-style farm, much like the serene Terhune Orchards I visited as a kid, also in suburban New Jersey. Dawson wrestles with the disconnect between this idealized farm that his kids see, and the factory farming that produces the actual meat that the kids are eating for dinner. Dawson plays with three visual levels here: black and white ink wash for their visit to the farm, bright colored coloring book-style drawings of animals, and visions of factory farms in harsh blood red. (This strip was actually an instrumental factor for me deciding to try going vegetarian again, after going back to eating meat for a couple of years.)

A couple of stories and elements, however, disturbed me deeply, I believe for the wrong reasons—by which I mean, unintended by the artist. Cartoonist Cathy G. Johnson broke down one story that appears collected in this book in an essay for The Hooded Utilitarian blog called “The Trick of ‘Overcompensating’”:

“The danger within [“Overcompensating”] is the creation of excuses for abusive behavior. The Narrator never outwardly admits he was abusive. He gives us statistics on domestic violence, but he never once owns his actions as wrong or violent towards his ex-partner. He gives us events and excuses for them. We are meant to read into the story that his actions were possibly abusive, while at the same time casting doubt upon that assumption. This story is a distortion meant to create empathy, a story developed in his point of view and his point of view alone.”

I was happy and relieved to read Johnson’s piece, because I had felt confused and fucked up reading the story. I wordlessly wondered something I often had as a survivor: What is it that I’m seeing? Can I trust my own reactions? Pete Hamill wrote in the liner notes to Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, “Totalitarian art tells us what to feel.” Power distorts, as Johnson says, and so Dawson’s authorial power distorts the reality of the situation by cutting out the potential feelings of the man he confronted and tried to beat up, and the woman, his ex-girlfriend who, we can assume, would have likely felt threatened in the wake of the outburst. As Johnson points out elsewhere, Dawson makes a confusing attempt to portray himself in the story as comic figure, when he was likely anything but for people in that situation. Having been abused, I can say that in my experience, the only laughter I had was bitter.

A story that begins with the phrase “Americans love an underdog” suffers from similar oversimplification. Dawson theorizes that the white liberal need to cling to the myth of a post-racial America comes from the general problem of believing in the story of the United States rather than a reality. It’s not a new thought by any means, and part of its violence comes from not citing or referencing the many, many black sources that Dawson would have been reading these thoughts from on Twitter and elsewhere—people like Amadi and activist Che Gossett. However, Dawson falls on the easy solution of using mostly “redneck” stereotypes as the anti-black antagonists, denying complicity.

A story that begins with the phrase “Americans love an underdog” suffers from similar oversimplification. Dawson theorizes that the white liberal need to cling to the myth of a post-racial America comes from the general problem of believing in the story of the United States rather than a reality. It’s not a new thought by any means, and part of its violence comes from not citing or referencing the many, many black sources that Dawson would have been reading these thoughts from on Twitter and elsewhere—people like Amadi and activist Che Gossett. However, Dawson falls on the easy solution of using mostly “redneck” stereotypes as the anti-black antagonists, denying complicity.

Some of the book’s successful parts comes from visual rhymes, courtesy of drawn elements by Dawson's 6-year-old daughter. Several small self-portraits appear, some of them racked with anxiety. This thread comes together in the last story, in which Dawson's daughter brings home a drawing and some text she'd written, from a prompt to write about a difficulty in her life. Her piece gives Dawson pause, because she'd written about his getting short with her when she rode her trike while he was trying to get her and her little brother to go somewhere.

"On the other hand," he says, "As she gains the tools of her own self-expression, I gain a window to my child's inner life... Obviously I've always known on an intellectual level that my children are wholly separate beings from me. They have their own desires and their own perspectives. But, I feel like really grasping this has been something I've had to do in increments. I can't wait to see more."

The second to last page repeats Dawson's hand-lettered phrase "Am I good?" Dawson uses this sentence as a leitmotif through the book, but the reification unfortunately pushes this final story from sentiment to sentimentality, which also reveals a key flaw within Dawson’s overall argument. Some of best moments in Dawson’s narratives seem to posit that the question “Am I good?” may not be answerable. Other stories, such as “Overcompensating,” remind that the author, while he acts like a spectator, is a willing participant in his own narrative. I would have been more interested to hear Dawson ask himself, “Are my actions good?”