Igor Hofbauer’s stories niggle at the dark recesses of the psyche. They are visits implying there’s much more to face, panels awaiting uncovering, but we don’t want these scenes of extended hideous horror to be so easily explained or, for that matter, to come much closer. Most of his main characters are physically deformed in some way. And in ‘Desmond’s Saliva’, a prison escape unleashes page after page - thirty-plus of them, in fact - of an unceasing, unflinching train through the carnage of a flesh-eating virus attack on the public. Hofbauer has an ingenious way of bringing us into a story, of dancing with the subject along the outer perimeters until it’s ready to become explicit. For example, the first page of ‘The Nail’ opens on what might be an aerial shot of a volcanic island, moving to a woman on her knees cleaning the bloody floor underneath a giant rib cage of a carcass still holding some meat, then this same woman is pictured on a primitive surveillance device held by a man we then see to be walking through a city. This lays the foundation for a brutal tale of control and revenge whose supernatural elements serve to further confound and keep the reader firmly in the grip of its psychogeographical nightmare.

Hofbauer is also a master of presenting many different psychological aspects at once. This occurs even in the shortest stories but is particularly true of the two major works in this collection, ‘Olympia’ and ‘Plastika’. Each a tour de force, these two vast worlds complement each other like shadows. Both are meditations on the interaction and interconnection between artists and their publics. And like the rest of Hofbauer’s work, what lies only millimeters beneath the already darkened surface is sinister and gruesome. The metaphor is obvious in ‘Olympia’ with a retired pop singer now living in a zoo. Her caretaker is under investigation by a policeman with a hidden agenda. But even while the prevalent mysteries are eventually clarified as the tale moves past its grisly conclusion, the sense of wonder that has built up in the reader’s mind is never dispelled. The victims of ‘Plastika’ (the titular character an old bag lady) are more innocent. Elaborate operations are in motion – one using a homemade periscope, another a makeshift hypnotic theater – that are never fully explained. Nevertheless, we sense the various connections and motives that Hofbauer has effortlessly weaved within. These stories contain so much more as well, ideas that lurk on the boundaries of consciousness, formless questions despite having been led through a plot.

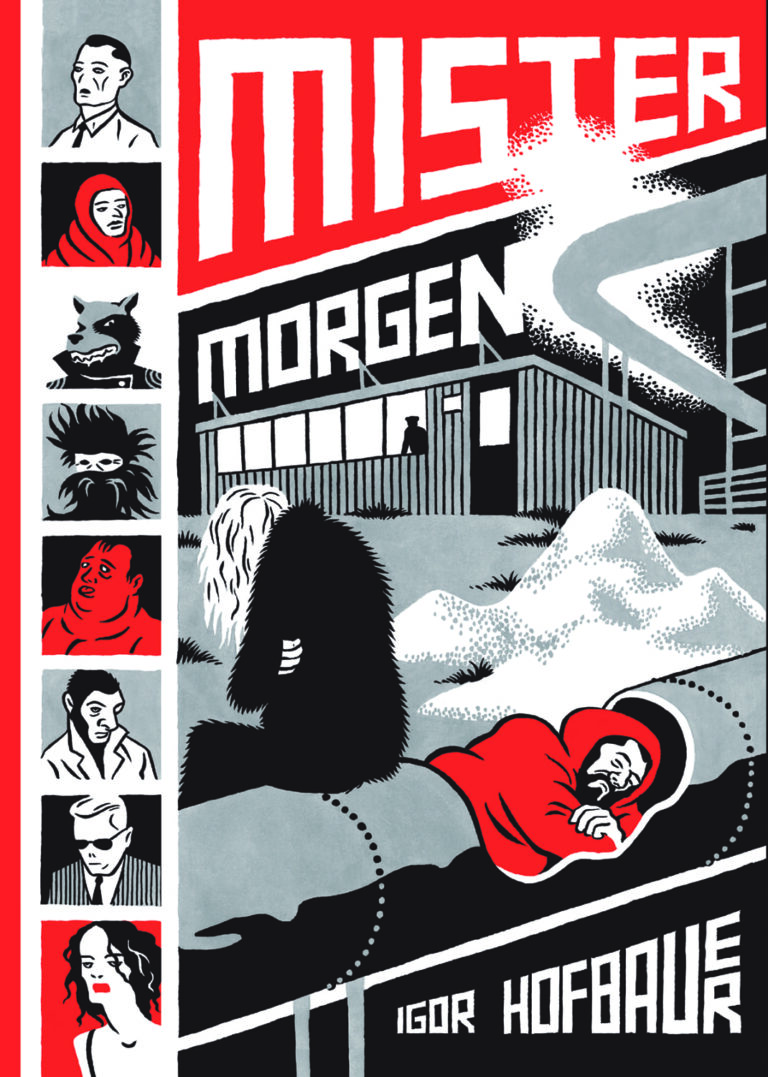

Comparisons have been made to Charles Burns’ artwork but Hofbauer’s is more stark. And while black and white, it is gray – that Eastern European gray – that dominates the panels. The only color present is red, used very sparingly to draw in our focus. More often than not, the red is blood, bringing our attention then to the essence, the essential. Perhaps even to life, or life-energy. Red appears most prominently in the sex scenes of ‘Danilo’ (also the most surreal story in the collection) and ‘Injustice’. But there’s no love or warmth in these actions, they are an escape from everyday drudgery and misery. And even more than lust, the depiction of sex is about voyeurism. People watching people, and all that leads from there, most notably control, is a major theme in Hofbauer’s work. A native of Croatia, it is easy to see the corruption and fall-out of Eastern Bloc politics behind all of Hofbauer’s comics. Known for his poster art for music and festivals, ‘The Band You’ve Never Heard Of!’ is the most rock n roll of these tales. Its second page is wonderful with burning tires and a tear gas container providing smoke rings around the reminiscences of this outlaw band of dogs as a lone masked figure rises to oppressive power. The stories are filled with poor and destitute characters. Throughout the book multiple impoverished persons are selling their belongings on the street. ‘Mr. Morgen’ sees privilege briefly coming face to face with the segregated poor. This title character of the title story is unnamed throughout the panels, reinforcing how even the humanness of the poor has been taken away from them.

Comparisons have been made to Charles Burns’ artwork but Hofbauer’s is more stark. And while black and white, it is gray – that Eastern European gray – that dominates the panels. The only color present is red, used very sparingly to draw in our focus. More often than not, the red is blood, bringing our attention then to the essence, the essential. Perhaps even to life, or life-energy. Red appears most prominently in the sex scenes of ‘Danilo’ (also the most surreal story in the collection) and ‘Injustice’. But there’s no love or warmth in these actions, they are an escape from everyday drudgery and misery. And even more than lust, the depiction of sex is about voyeurism. People watching people, and all that leads from there, most notably control, is a major theme in Hofbauer’s work. A native of Croatia, it is easy to see the corruption and fall-out of Eastern Bloc politics behind all of Hofbauer’s comics. Known for his poster art for music and festivals, ‘The Band You’ve Never Heard Of!’ is the most rock n roll of these tales. Its second page is wonderful with burning tires and a tear gas container providing smoke rings around the reminiscences of this outlaw band of dogs as a lone masked figure rises to oppressive power. The stories are filled with poor and destitute characters. Throughout the book multiple impoverished persons are selling their belongings on the street. ‘Mr. Morgen’ sees privilege briefly coming face to face with the segregated poor. This title character of the title story is unnamed throughout the panels, reinforcing how even the humanness of the poor has been taken away from them.

For Hofbauer, the horror never ceases. Through recurring characters and similar landscapes of urban wasteland, these tales are connected in the way troubled dreams will stem from a common root. Affliction and depravity are all too apparent, but like dreams, or rather nightmares, Hofbauer’s work contains much creeping behind the horizon of the visible.