From The Comics Journal #104 (January 1986)

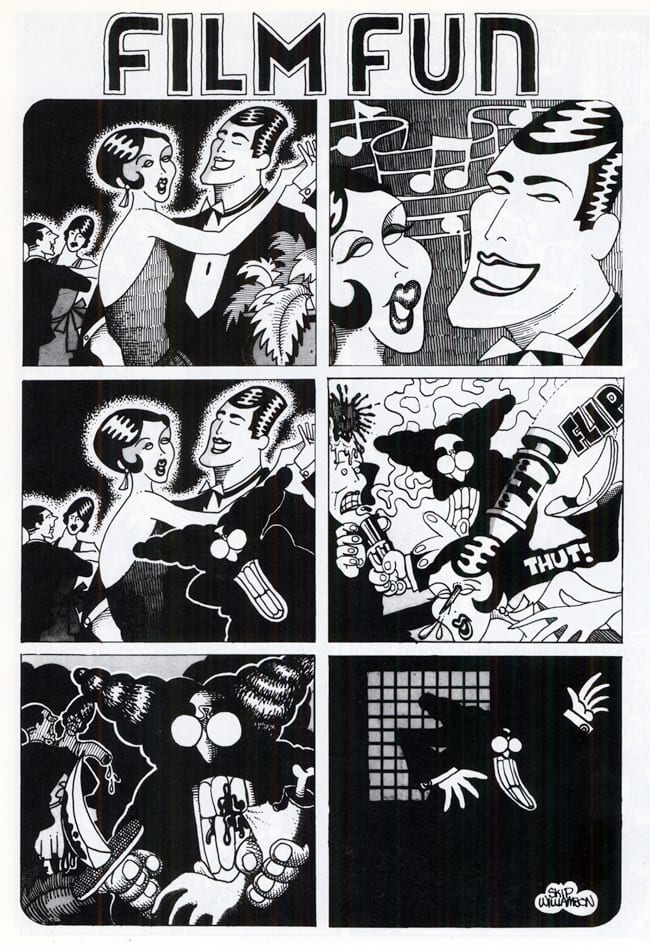

Of all the underground artists, few seem as simultaneously linked to their moment yet transcendently funny as “Flippy” Skip Williamson. With his flat-blacks and obsessive crosshatching, his broadly self-reflective caricatures, Williamson's combination of Kurtzman-inspired cartoonery, hallucinogenic political analysis, and midwestem moralizing made him the ideal reporter of Life in the Hog Butcher circa '68–'74. The most political of underground humorists (in the most thuggishly political of American cities), Williamson began as just another fanboy artist in the days of many Mad-imitation fanzines, gravitated to the Chicago alternative press (first in Jay Lynch's short-lived magazine Chicago Mirror, later in the Seed plus sundry Yippie-edited papers), then joined forces with Lynch and R. Crumb in producing Bijou #1, one of the earliest, longest-running undergrounds.

Williamson's underground style, steeped in Art Deco flatness and crammed with calculatedly unhip scatology (“Holy cow! Some elephant doody!”), carried the same joyful resonance―the love of doing comix that nobody would've dared to do 10 years earlier―that sparks Crumb's early work. But where Crumb's primary comics aim was introspective, concerned with the character of those living through the '60s (himself included, of course), Williamson took a broader look, skewering both left-wing trendiness and rightwing overreaction to a time of much-publicized leftwing trendiness. Crumb's approach may have been more personal, more artistically “legitimate,” but to those of us struggling to make sense of the sociopolitical chaos, Williamson was frequently the funnier.

Bijou #1 first introduced Snappy Sammy Smoot, Williamson's middle-aged innocent in confrontation with the times. A compulsive and naive nice-guy, brilliantined Smoot strove to find his place in the volatile counter-culture, only to be repeatedly mauled and exploited by the folks he thought were on his side. Despite his open alignment with leftist radical politics of the day (exemplified by Conspiracy Capers, a Williamson-edited one-shot done to raise money for the Chicago Seven), Williamson maintained a satirist's skepticism about the era's elevation of rhetoric over humanity. In “Sammy Smoot Gets Assassinated” (Bijou #3), for instance, our hero is killed by an “over-zealous” government man, given the chance to return to life by the devil only to be stomped to death by zealous radicals rioting in protest of Smoot's first demise. The road to hell is paved with zealotry, Williamson seems to be saying.

Sammy Smoot lived through it all―drug experimentation, Weather-styled revolutionary mayhem, hip Christianity, serial killing, intergalactic encounters―with his innocence unscathed. (Compared to Sammy, Candide was a hardnosed intellectual.) In later issues of Bijou, Williamson introduced Ragtime Billy, a rightwing foil based on the midwest radio commentator Paul (“Fellow Americans”) Harvey. Crew-cut and loudmouthed, unswerving in his dogmatism, Billy thrives where Sammy gets victimized, a comment both on the rapid-fire obsolescence of the period's countercultural trends and our country's unwaveringly conservative backbone. In one strip Billy wiped out most of the United States with a broadcast of his bigoted diatribe yet remained unpunished. (One can't help but think today of our current regime's reluctance to pursue present-day reactionary abortion clinic bombers―or to even label them “terrorists.”) If anyone really wishes to know when the promise(s) of the '60s and early '70s weren't realized, all they need to do is read Skip Williamson's Bijou strips.

In more recent years, Williamson has maintained a more mainstream (I'm tempted to say “Yuppie”) profile: appearing in Denis Kitchen's failed attempt at reaching the Marvel audience, Comix Book; working as art director for Playboy (an experience he, typically, would satirize in one of his Comix Book strips); as well as producing a strip for Playboy's comics section. But for those who lived through the political and cultural quagmire that was the underground era, Skip Williamson is still the quintessential underground comix artist.

―BILL SHERMAN

GRASS GREEN: Well, Skip, it's nice being in your office again. I'm wondering, how many of your fans would know that you work for Playboy, and have worked for Playboy for … how long?

SKIP WILLIAMSON: It'll be eight years in October, 1984. It depends on how close people can keep in touch with what I'm doing. Playboy's a mass magazine, I would think that more people know about Playboy than knew about the underground comics. I mean, Playboy's circulation's a lot more than Bijou's was.

GREEN: Twenty-eight, 30 million.

WILLIAMSON: Not that many. It's a broad audience, but it's probably a different audience. A lot of people don't read Playboy, too. And some of the people who read the undergrounds don't read Playboy. I constantly come across folks who say, “Oh, I didn't know you were there, I don't buy the magazine because it's too expensive,” or, “I don't like it,” or some reason or the other.

GREEN: Well, now they'll find out. Because even―I won't mention any names, but even a person of high rank with The Comics Journal wasn't aware that you were an art director at Playboy.

WILLIAMSON: Even in the early days of the underground comics, I've always held a job working in an art studio of some kind, as a designer. I even designed the Post Raisin Bran cereal box. Started out as a keyliner, that's where everybody starts out, I think. Then, in the meantime we did the comics, and I worked my way up through various magazines art directing, and then up here, which is fairly illustrious, really, in terms of art directing magazines. I can virtually go to any artist I want. It's been a learning situation for conceptual thinking, which is a lot like writing cartoons.

GREEN: Yes, and 1 think that the idea that working for Playboy, the kind of cartoons and stuff that they use, any of the old lechers like me, who come up with a really good idea regarding sex and all that kind of stuff, they still have this outlet, without being considered the old style pornographer, you know? I mean, get to draw T & A, boobs.

WILLIAMSON: Around here you can be as soft-core as you want.

GREEN: I'm not talking about the gross-out stuff like would be in certain other publications.

WILLIAMSON: You mean in Hustler? You know, I was the first art director for Hustler magazine. I worked with Larry Flynt for about two weeks, and the only thing I really art directed for him was the cover of the first issue and then I left, I quit. But, historically, I was his first art director. So I've been in the tits-'n'-ass business for years. [Laughter.] It's true, I worked as art director for Gallery magazine when it was in Chicago, for the last six months it was before it moved to New York City. I've also worked in massage parlors. So you know, I've worked the seamy side of the street.

GREEN: All right. Need an assistant? I was going to ask you if you still do Snappy Sammy Smoot.

WILLIAMSON: I've just started a new Snappy Sammy strip. The only problem is that there's no real outlet for it, but I've started one anyway. It'll probably end up being 10 or 15 pages long. Snappy Sammy being tax audited―

GREEN: I've been through that.

WILLIAMSON: Me too. Every year, they come and get me. In the strip Smoot is audited and then he goes home. Ragtime Billy's there, and Snappy Sammy's three nephews live with him now. They look just like Snappy Sammy Smoot, except they got punk haircuts, and their names are Huey, Dewey, and Newton. And one of them's black. I'm doing this strip just because it struck me that I wanted to. I don't know where or if it'll be published, but I'm writing. In it Ragtime Billy suggests that Smoot go to a survivalist camp to get away from this tax problem duty.

GREEN: Do you think that the underground market will ever return? Even on a limited, less hostile, less super-duper unedited basis?

WILLIAMSON: It's still around in some form or the other. I don't think it'll have the vigor it had initially. When you come up with a new form like that, there's a lot of creative energy, and a lot of excitement. There were a cluster of good artists, of course, like Crumb, and Shelton, and Jay Lynch, and all the other people who were involved in the first wave of underground comics. I don't think you'll find that kind of vitality in the second wave or in the new wave of comics. There just isn't the intensity of energy that there was in the early days, in the late '60s and early '70s. It's a progression, it evolves, it continues, there are other ways for people to vent their work, through places like Playboy. There's Playboy Funnies, you know. There's the Lampoon, there's Heavy Metal, there's RAW, there's Weirdo. There are a lot of different directions to go. But few of these markets have anywhere near the creative freedom of the original movement.

GREEN: But, there are so many artists nowadays. Clay Geerdes has this little mini-comics thing, and that's a nice outlet for people who can't draw but have this need to express themselves to somebody, if it's 10, 15, 20 people.

WILLIAMSON: And there's Weirdo. Weirdo's publishing some artists that I haven't seen. And then of course, there's RAW Magazine.

GREEN: I've heard a lot about RAW, but I don't think―

WILLIAMSON: RAW is Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly. Art was one of the original Bijou boys. RAW has more of an art with a capital "A" feel to it, it's a little more serious than some of the goofy stuff that I do. But it's well done, and it utilizes new artists, a lot of innovative art, and an experimental, large-page format. That's real nice. A class magazine.

GREEN: You mentioned Jay Lynch among others. You've known him for a while, haven't you?

WILLIAMSON: Jay's an old friend. We started out in the fanzines together, corresponding with each other. This was when I was 15, 16 years old, and the only reason I moved to Chicago was to come up and be with Jay, and start a magazine of some sort. He originally had the idea, and this was before the advent of underground newspapers, around 1963 or so, of publishing something called the Old Town Underground Newspaper. We never did. When I did finally move to Chicago in 1967, we started the Chicago Mirror together, which was kind of a magazine somewhere between the Realist and Mad. It had a lot of psychedelia in it, too. After we did that for three issues, we said, “Hey, we should be doing comic books.” Robert [Crumb] had come out with Zap and Gilbert [Shelton] was about to publish Feds 'n' Heds, so we converted the Mirror to a comic book, named it Bijou, and that's how the whole thing began. Anyway Jay's always been a strong influence, and a partner. We see each other less now, but we talk on the phone all the time.

I might also say that the concept of Bijou Funnies is not over with. I've been talking to Jay for some time now, and suggesting “Let's do a Bijou that would be like a humor magazine.” I've got another Snappy Sammy Smoot strip. Maybe we'll come out with another issue. We probably will. It's an open-ended project. It's been a long rime between issues, but so what? It's a flexible format and you can do that.

GREEN: When people read this, that should give them something to look forward to.

WILLIAMSON: Hope so.

GREEN: I'm certain that you have gobs and gobs and gobs and gobs and gobs of fans out there, wondering, “Hey, whatever happened to Skip Williamson? I'm dying to see something new by Skip Williamson.”

WILLIAMSON: I'm still around. I'm doing new things all the time. There were some strips in Playboy Funnies, although I tell you, I'm disillusioned with Playboy Funnies. I find them consistently unfunny, and the project stale. I've drawn back from it. I was doing a series called Neon Vincent's Massage Parlor, which is the perfect Skip Williamson vehicle, because the protagonist looks like an insect. He's a real sleazy kind of operator.

GREEN: He's got that long mouth and that cigarette sticking out.

WILLIAMSON: Kind of like an anteater look.

GREEN: Yeah! yeah, exactly.

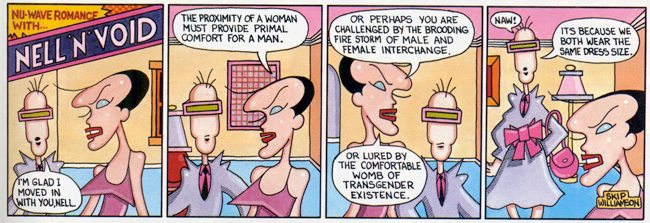

WILLIAMSON: He never takes that cigarette out of his mouth. Then I was doing a series called Nell 'n' Void that I liked a lot. Nell 'n' Void were a new wave couple, but Playboy decided not to use it any more. They said, “This whole new wave thing is over.” That was three years ago, and I think it just permeated the culture. I'm upset by their lack of humor. I helped initiate the Funnies. Playboy brought me in because I knew comic strips, and said, “Would you put together a funnies section?” So I went to New York, and assembled a group of artists, with Michelle Urry and the cartoon office. We came out with Playboy Funnies, which has been in the magazine ever since, every month. But then, when I stick with a project for a while, I tend to get bored with it. I don't want to be stuck in a rut, especially under the rule of the bund.

GREEN: It's true, the Playboy Funnies, like a lot of the daily strips, they're supposed to be funny, and they're not. Every now and then Playboy has something in it that really cracks you up, though.

WILLIAMSON: I find that's seldom true of the Funnies. I find that unfortunately it does look too much like the Sunday papers. The jokes are consistently weak. There are some interesting things, but by and large, the Playboy cartoon office is an inhibiting factor. But I've continued to cartoon and I've been negotiating with Denis Kitchen, of Kitchen Sink, to publish a sketchbook collection of cartoons. I've written a lot of strips that have not gone into final, or a finished stage, but they're clean and well written. I've also been painting on canvasses for about nine years. This was kicked into high gear by the Carl Barks duck paintings. When I first saw those I said, “Wow! That's a really nice concept. Cartooning on canvas.” Eventually I'll put together a show of my painting. Another thing that I've been working on is a cartoon history of Hugh Hefner. [Laughter.]

It involves about 32 separate cartoons, and they are mainly gag type cartoons. I can be very flexible with it, and Hefner is hot on the project. It's called “Hefner for Beginners,” and it's designed to be a six-page cartoon spread in the magazine. Which will be real interesting, full color, the whole shot. When I first presented the idea, the editors were a little skittish, because of my sense of humor. I tend to be a little vicious at times. They were scared to take it out to him. But when he finally got a look at it, Hefner said, “You're letting this guy hold back too much, let him get freer, let him go after the jugular if he feels like it, that's his style.” Hefner is very good that way, because he's always been a frustrated cartoonist himself. He has great admiration for cartoonists. The first time I ever met Hefner, we sat down and we talked for a long while about cartoons. Talked about Jack Cole, talked about people he liked, people I like, and it was just a very nice casual thing.

I've been writing a lot. I'm working on producing, directing―as well as having co-scripted―a feature film called TV Dinner. It may be released through Playboy cable, if they want to pick it up. It's funny, it's very visual. It's unlike a lot of the talky kind of sitcoms, or even Saturday Night Live, that sort of thing. It's more visual. You'll see the cartoon influence a lot. It's very fast-paced, and we're going after characters, exaggeration, and lots of bright colors. So, there's been a lot going on. I've done quite a bit of illustration, too, over the years. Eventually, I want to put together a collection. But is there a market? Are there people out there who are willing to lay down the bucks for a collection of Skip Williamson art?

GREEN: Is this the book you have lying in wait? Wow! I am looking at a veritable stack of Skip's work, folks. It's black-and-white, but it's beautiful from right here.

WILLIAMSON: There are some color things in there. It goes to when I was in college―you know, cartoons, sketches, and some commercial things … posters, caricatures. Here's one of Slim Whitman. Slim Whitman's great because he looks like he would have been drawn by me. He's like a real Skip Williamson character, you know?

GREEN: When you work, do you work better days or early mornings, late nights? When is your best hour of production?

WILLIAMSON: Right after I've smoked a joint. [Laughter]. It really doesn't matter. My schedule now is that of having babies, so I'm in bed early, and up early.

GREEN: And kind of watch where you smoke the joint.

WILLIAMSON: The first rule of parent-dom is don't pass the reefer over the crib, but I digress. I don't work at night that much any more.

GREEN: What's the real story behind you and the Cripple Creek Colorado thing?

WILLIAMSON: That is a long story, I don't know if there's time in this interview. It's a whole other project. I'm writing a book about it. I've been plugging on this one for some time and it's a true story. It happened in 1965 … it's the story about how I was kidnapped by mafia lesbians who drove Good Humor trucks in Kansas City.

GREEN: If you're writing a book, then don't tell us.

WILLIAMSON: I'm not going to give it away to you. All that I can really say is during that summer, I worked publicity for a transvestite review in Cripple Creek, Colorado. I was going to school, it was a summer job, and I was still living with my parents. In the process of things that happened, the FBI, the Illinois Youth Commission, and the State Police of five states were looking for me, and the FBI told my parents that I had been murdered.

GREEN: That's enough, I want to read the book. You've been with Playboy eight years?

WILLIAMSON: Yeah. I'll tell you something else about Playboy. It's a good learning situation in terms of art direction.

GREEN: You could go almost anywhere, couldn't you?

WILLIAMSON: This year I've won two awards from Communication Arts, a silver award from The Society of Illustrators and one from Print, and a gold award this year from the Art Directors Club of New York City. It's concept-oriented work, as I mentioned earlier. It's a lot like cartoons. For instance, I did a layout on journalism news wars, network TV news wars. And the idea I came up with was a hand grenade. Each one of the little segments on the hand grenade is a TV screen, with a different newscaster on it. And I just did a piece with Boris Vallejo.

You know, who I'd love to work with is Don Martin from Mad magazine. I'd love to do a piece with him. He sent his portfolio, and as soon as something comes along, I'm going to assign something to him because he's always been one of my favorites. One of the original crazy cartoonists, you know.

GREEN: Yeah, really. Did you do stuff for Abbie Hoffman?

WILLIAMSON: Abbie? I was always more political than most of the other underground artists. Or anti-political. I believe honestly that if you vote for these bastards, you only encourage them. They're all a bunch of thieves and crooks. There's no government like no government. I'm a philosophical anarchist, a social sore on liberty's privates―always have been. And, so, during the big upheaval of the late '60s, I naturally became involved with a core of people. The ones who really appealed to me were the Yippies, because at least they had a sense of humor about the whole thing. I ended up editing a comic book to raise money to pay for the conspiracy trial. I did a little bit of hanging out with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin and those guys, and published that comic book, Conspiracy Capers. That's about the extent of it. See, I'm reticent even to admit that kind of connection, because that aligns me with a group of people in the same sense that it would align me with, say, the Republican Party.

GREEN: Yeah, some political group.

WILLIAMSON: It's still a political group and I don't need to be categorized or aligned with any specific group. I liked the Yippie energy but where are they now? Jerry Rubin is a stockbroker, Eldrige Cleaver is a Nazi, and Abbie Hoffman is a liberal.

GREEN: Everybody passed through that phase and went back to the establishment that they were fighting in the first place.

WILLIAMSON: Here's what happened to the radicals, I think. In a Third World country, they'd line them all up and shoot them. In Mexico, during this period, they had student demonstrations in Mexico City, and they shot over 200 students. Now what happened here―this is your basic white Anglo-Saxon country, right? And all these young white kids from the colleges came out onto the streets and said, “Hey, we don't like it any more, we're going to tear it down.” All the authorities had to do was waste four of them at Kent State, and the kids changed their minds. And that's what happened, that's the difference.

GREEN: In all these countries where the people don't have all that much, and they don't have much to lose, it's easier for them to become suicidal with their mission. But Americans have too much to live for: “You shot down my buddy … well, shit.”

WILLIAMSON: Yeah, “"I'm going to stop throwing bricks at the cops and to make some money. The Revolution is over and I won.” I think that was the attitude of a lot of people.

GREEN: I'm kind of jumping around here, but how did you get your job with Playboy? We know you've been with them for a while, but were you shaking with fear when you first came in?

WILLIAMSON: No.

GREEN: You had that kind of confidence?

WILLIAMSON: In our early days as cartoonists, both Jay and I wanted to be published in Playboy magazine. That was during the heyday of Playboy, in the early '60s. It was the hip magazine of the era. They were publishing Ray Bradbury, Jack Kerouac, Lenny Bruce. We admired this, and wanted to be part of it. Actually I had been published in Playboy long before I'd began working for the magazine on salary. As a matter of fact in 1969 or '70 when Playboy did an article on underground comics, I did the opening illustration for that piece. That was the first illustration I executed for the Big Bunny. So from then on, I would get illustration assignments.

GREEN: I got that issue, because I remember thinking, “Boy! Skip's stepping up.”

WILLIAMSON: So anyway, eventually, I got a job working for Playboy Press, which was their book division. Not with the magazine. I worked as a designer, designing paperbacks and flats, that sort of thing. So at least I got to know the people. Then I was away for a considerable period of time, and at some point in my life, got fed up with the job I had and went to see an art director here, Roy Moody, and said, “Hey, listen, are there any art director's jobs available?” It just so happened, it was really a matter of luck as well as I guess talent, but there was a job available, and I was hired by Art Paul. And I've been here ever since.

GREEN: What was your favorite college humor magazine?

WILLIAMSON: Texas Ranger. Well, it varies, my first influence in terms of college humor was probably the Texas Ranger, because I was born in Texas, my daddy got his doctorate at the University of Texas. This is when I was 10 or 11 years old. And, of course, I'd see the Texas Ranger all the time. There was a guy drawing in there by the name of Gilbert Shelton, who was an undergraduate student at that time. I moved out of Texas a few years later, Jay and I began drawing cartoons for Bill Killeen and some boys in Gainesville, Florida. They had an off-campus humor magazine called Charlatan. Shelton was drawing for them, too.

GREEN: He got around.

WILLIAMSON: Later Jay became the art director of Aardvark, The Kicked-off Campus Humor Magazine for Roosevelt University in Chicago.

GREEN: Okay, my next question brings us to one of my all-time favorite publications. I don't remember your work there so much as I do Gilbert Shelton's. And that is, Help! magazine.

WILLIAMSON: Help! was the first magazine to accept a cartoon of mine for national publication. Harvey Kurtzman had the vision to publish the drawings of Jay Lynch, Robert Crumb, and Gilbert Shelton in Help!, and that was the basic core of underground comix. And I think that says as much about the corrupting influence of Harvey Kurtzman as does anything. We were real neophytes at the time. I look at those early drawings and they're bad. But there was a glimmer of humor, and you've got to start somewhere, and that was a place to start. Help! had a section called the “Public Gallery.” They'd pay you $5 a cartoon. Nineteen sixty-one was when I had that first cartoon published. I was in high school. This was the time of the early civil rights struggle. The subject of the cartoon were two garbage cans in New Orleans. One said “Negro trash,” and the other said “white trash.” It was printed in the issue with Hugh Downs on the cover, #8. I think it was also mentioned on the old Jack Paar show. Jack Paar was the host of the Tonight Show before Johnny Carson. Dick Gregory was on. He mentioned the cartoon, and boy, what an ego boost for a high school kid in Canton, Missouri. That really gave me a shot to want to keep going. By the way, you might be interested to know that the editor who accepted that cartoon was Gloria Steinem.

GREEN: I wanted to ask you what you thought of a few artists. What do you think of Robert Crumb?

WILLIAMSON: Robert's the best! In terms of craftsmanship and ideas, he was the progenitor of this whole movement, so you've got to respect the guy. I think he's getting a bit crankier these days, but that's part of his charm. He's the irascible guy.

GREEN: Okay, how do you feel about Shel Silverstein?

WILLIAMSON: Shel's become a friend of mine since I've been at Playboy. I'll tell you how I met him. He was in town working on a collection of cartoons called “Different Dancers” that was going to be published in an oversize format. And he was stuck, he had a cartoonist's block, a writer's block. So Shel and I sequestered ourselves in his hotel room and worked it out. Shel was one of my influences, even though Shel tells me he can't see it in my drawings. He's been doing this stuff for eons. He's a guy that really, I think, understands about not putting yourself in one narrow category. Take off the blinders and don't self-incarcerate your talent. Spread the gift from plateau to tier to plateau.

GREEN: I've always loved his spreads in Playboy. How about Gahan Wilson?

WILLIAMSON: Gahan Wilson was at one time more of an original thinker although I have admiration for his work.

GREEN: The stuff's still funny.

WILLIAMSON: When I was in college, and I was just trying to be a cartoonist, I sent him some of my cartoons. He took the time to write me back a three-or four-page letter, explaining what he liked about them, what he didn't like about them. And it was considerate of him, at his peak at that time, to take the time out for some kid he didn't even know, and do that sort of thing, I thought was very sensitive and very good. It's important for a young talent to hear from professionals whom they admire and respect because it does give them the impetus to push on.

GREEN: What do you think of Jack Davis?

WILLIAMSON: I've got an original Jack Davis. A color cartoon he did for Playboy in 1963. I treasure it. Some of his recent work is commercial, but he's making a lot of money. He's not working with the great detail and finesse that he did when Kurtzman was his editor. He's one of the artists who work on a tight deadline. He likes to play beat-the-clock. When I was young, I used to trace Davis all the time. I paid a lot of attention to what he was up to.

GREEN: What do you think of superheroes?

WILLIAMSON: I'm much more interested in humor. I've used superheroes as an influence, though. I did a strip called “Super Sammy Smoot battles to the Death With the Irrational Shithead.” So I used the form. I'm not knocked out by superheroes … Get it? I met Neal Adams when I was in New York. He reminds me of Jimmy Breslin. He sits back and smokes cigars and tells you what he thinks of you. I'm influenced by superheroes in the same sense Harvey Kurtzman was influenced by superheroes to write “Superduperman.”

GREEN: Satire.

WILLIAMSON: Yeah. Although I have admiration for the technical skills of a Jack Kirby or a Steranko.

GREEN: Okay, that's what 1 was going to ask you next, about Jack Kirby. Because he's my main man.

WILLIAMSON: I can look at it, and say, “Boy, this guy really knows how to draw musculature.” I like Rich Corben a lot. Corben sent me a couple of strips that I forwarded to the cartoon office. Shel Silverstein and Rich and I were working on the project for Playboy once that didn't get very far. It kind of fell through the cracks. Corben felt like he was losing control over it. He was right.

GREEN: I was making the mental notations of the difference between you and Jay. Jay is more the historian, and he's a little bit more soft-spoken while with you, you're kind of like me, an animated talker, and you really like what you're talking about.

WILLIAMSON: Jay has a perceptively bizarre perspective of the universe, and probably his best quality is his canny vision of the way things operate. When you talk to him, you get insight.

GREEN: Yeah. He once told me how to do the definite super-selling superhero, and he's not even interested in the thing. If I can ever sit down and get him to talk at length on the subject, enough to grasp the idea he's talking about, it makes sense to me. But compared to me, Jay has a photographic memory. He just tells me so much stuff, it just boggles my little weak brain, you know? He carries a lot inside his brain.

WILLIAMSON: Yes, he does. We're two different personalities. Maybe one of the reasons we work so well together has to do with that.

GREEN: Opposites, yeah.

WILLIAMSON: I don't know if it's so much opposites, but it's differences. Jay is more of an intellect than I am. I think he does a lot more intellectual reading than I do, and he absorbs details and knowledge. Everything from the arcane to the political to the frivolous, he absorbs it. If you read Phoebe and the Pigeon People, there are references that probably escape most people, but who cares? It's great, it's wonderful, it's thought and cartooning. So if you only hit a small audience and make them laugh and think, who cares?

GREEN: Well, his strip is running regularly in the Chicago Reader, so that attests that somebody is digging it, or else it wouldn't be there that long if nobody liked it.

WILLIAMSON: I don't mean to say it doesn't have an audience. A lot of people like it. He's very popular with art students at the Art Institute of Chicago, I know. And, I'm sure, elsewhere too. Of course, he's had the collections of Phoebe published, too. You know, it's an interesting story. I was doing the strip for the old Chicago Daily News, called Halsted Street―Stories of Torment and Drama from the Hog-Butcher. At this time, the Daily News was in its final decline, and they were about to go out of business so they were trying to save it. What they did was come up with an idea for a supplement called “Sidetracks,” which was like an underground newspaper, stuck into a regular daily newspaper. It came out once a week, every Thursday, and I did this strip. Jay took the idea of Phoebe and the Pigeon People to the editors, and they just did not understand, you know? They said, “Why are you here with these people-headed pigeons? We don't understand what you're talking about.” I didn't last very long with them either. Editors can be so linear. I finally offended everyone on the paper, when I suggested that hyperactive children should be stuffed, mounted on roller skates, and trucked off to Montessori parking lots. They didn't like that one. They said, “We don't think that was funny, and we don't want you to do comic strips for us any more.” I thought it was a funny notion.

GREEN: It's funny―people get their own little mental concepts of what the artist is like until they meet him in person.

WILLIAMSON: But that's pretty much the same with any recognizable artist, don't you think? People have a certain mind set from reading the work, and then when you meet the person he seldom meets your expectations, or he has a totally different kind of reality.

GREEN: You weren't as far off in my perception of you, related to what I'd read by you, as Jay was. I mean, in Crumb's stories, in his work and everything, he gets vicious, and just crawling all over women and everything. But they say that he's really very mild-mannered.

WILLIAMSON: Although you know what he's doing. Robert, as well as a lot of the underground cartoonists, are taking their inner selves, you know, that turmoil that's going on inside and putting it on to the page.

GREEN: I think that's what has made him so well-loved.

WILLIAMSON: I'm sure. He puts all the dark secrets out. Everyone's got similar neuroses and psychoses going on, so what he's done is said, “Look, I don't need a psychiatrist. I can write.”

GREEN: I think psychiatry is a bunch of bull poopy, anyhow.

WILLIAMSON: Some of the most fucked-up people I've ever met are shrinks. And speaking of shrinks, you know who's another artist we haven't heard from in a while, is Justin Green. Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, one of the great all-time comic books.

GREEN: He did a couple, didn't he?

WILLIAMSON: He did a lot for Bijou, too, he was one of our regular artists. Justin was another one of those artists that could take his guilt, in this case Catholic guilt and neuroses, and put down on the page, and resolve it in that fashion. He was one of the best―still is, unless he's stopped working―cartoonists of that time.

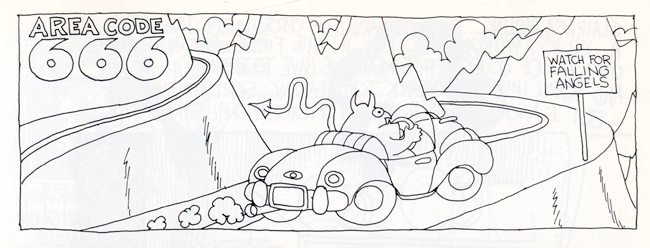

GREEN: I'm holding in my hand here a very beautifully rendered color strip, Area Code 666. And I could easily get off on a series like this.

WILLIAMSON: Area Code 666 is a mythical area that's inhabited only by Christs and Anti-Christs. Nobody seems to want to buy it. This is the only strip I've taken to finish. I have two or three other ideas, but I don't have a market. One of the problems with my art is that it tends to be so strange sometimes that there's no place to publish it, especially if I'm working in color. It's one thing to render something in black-and-white. There are probably a lot of places that would take a black-and-white strip, because it's less expensive to reproduce, but I really enjoy the color, the added impact of color is important sometimes. I've got another series that I'm working on, called The Butcher Shop of Love. The Butcher Shop of Love is like your neighborhood meat market. They've got big salamis and pulsating hearts in the case. The lady patron says to the butcher, “Is that a thumb on the scale, or are you just glad to see me?” I'm writing all the time, new ideas, new strip ideas, but there's no place to vent a lot of this material, never throw anything away. But I don't know where to publish this stuff. Playboy Funnies isn't interested. A lot of people think that I'm responsible for Playboy Funnies, in other words, that I put it together and edit it. That's not true. All I do is the layouts for 'em, and then I'll forward my own work to the cartoon office and they'll say yes or no. The ratio of acceptance is about 50-50, for all the Neon Vincents, for all the Nell 'n' Voids, for everything that I've done for Playboy. There are at least as many other strips as there have been published, so I have a reasonable selection of unpublished strips.

GREEN: I like your style too. Anytime you have anybody in a strip with a mouth like that―wide, big, open, showing lots of teeth, and tongue―I love it.

WILLIAMSON: Well, I like the exaggeration, that's one of the things I enjoy―the broad exaggerations, the possibilities of character.

GREEN: You also have some guys who are emulating your style.

WILLIAMSON: I would say, without being too bumptious, that I've rubbed-off a lot of people in terms of style. That happened fairly early on. Even advertising agencies would go out and hire people and say, “Do Skip Williamson.” But they wouldn't come to me.

GREEN: Well, they probably thought that you'd be expensive.

WILLIAMSON: No, I don't think that's it. I used to do a bit of advertising work. I've done things for McDonald's and United Airlines. I did pretty well one year, and then I went to meet the main art buyer for J. Walter Thompson, and he sat me down, and said, “Well, listen, political times have changed, the Nixon administrations's in, and you're out.” That's essentially what he said. He said, “You are just too political.” I was blacklisted. And also, the fellow who was my rep told me the same thing. I didn't get any advertising assignments after that. I'm beginning to pick a few things up here and there, but that doesn't interest me so much. The bad thing about advertising, you don't have much creative input, but it pays well. And of course, we've come full circle again, we've got Ronald Reagan in there, and he … it's the same old shit. The same basic asshole politicians and their spooks. They're all there.

GREEN: Well, I'll tell you: Reagan, whether you like him or not, in a way, he's not doing badly, and in another way, he is―like the way he's gnashed all the money going to the needy. But to me, our system pushes a guy. If he goes in, and he's relatively clean, our system is so corrupt that he can't get anything done until he's corrupt also.

WILLIAMSON: I think that's true. To pursue politics as a vocation taints the individual. What is the megalomania that makes a man want to pursue something like the presidency, in that sense?

GREEN: Sense of Power.

WILLIAMSON: Yeah, power. Ultimate power corrupts, ultimately. It's an old theorem but true. Ronald Reagan is sitting there wearing more makeup than Boy George with his finger on the button. He's the most dangerous guy we've had around in a long time.

GREEN: But I like him.

WILLIAMSON: You like Reagan? You're the craziest black man I ever met. I like that quality.

GREEN: But Reagan's not like Nixon.

WILLIAMSON: Nixon was this uptight guy.

GREEN: “I am the president.”

WILLIAMSON: Right, you could see the evil.

GREEN: I'm always making the point with the family when my niece starts rattling down about Dirty Reagan. But we had a born-again Christian like Jimmy Carter in there, who was too wishy-washy and trying to do the good things―you can't do that with these people in the world. I don't want anybody like Jimmy Carter in there again. They wouldn't even let the hostages go until Reagan stepped in. “Oh, this guy might push the button, we'd better let them go.” You know, just [snaps fingers]. Then they're out.

WILLIAMSON: Ronald Reagan might push the button. Then where are we going to be? You know, french fries. Plus, what kind of trade-off is 40 hostages for 300 dead marines in Beirut? I have no respect for any politician. Especially tight-assed publicly moral Republicans who don't give a shit for life and liberty. I really don't.

GREEN: What do you do to work off stress?

WILLIAMSON: One of the people that I worked with here at Playboy is a Senior Editor by the name of William J. Helmer, this Bill “Mad Dog” Helmer. Bill came out of Austin, Texas at the same time as Gilbert Shelton; they were both classmates together. And so there's always been a connection between “Mad Dog” and Shelton, and that whole Texas group of wonderful craziness.

I respect Shelton's sense of humor, more that any of the other underground cartoonists. A lot of it has to come out of Texas bravado. Wonder Warthog, the Freak Brothers all have that certain kind of bombast that you wouldn't find had Shelton not come from that background. I'm currently collaborating with Helmer on a number of projects under the sponsorship of the Mad Dog Artists and Writers Consortium. Apparently, Shelton is involved in this too. We plan to produce a series of books and writings through the Mad Dog Artists and Writers Consortium. Now, Helmer has also introduced me to the manly art of firing automatic weapons, so we go out, up to McHenry County or up north sometimes. I tell you, there's great joy in firing a Thompson sub-machine gun, or an Uzi, or a grease gun. It's wonderful stimulating activity. I even told my wife, Harriett, once: “Listen, one of these days, those Fascist bastards are going to come crashing through our doors, and drag me away kicking and screaming, can we please get an Uzi, so I can pick a few of them off before they get me?”

GREEN: Can you get a what?

WILLIAMSON: An Uzi. An Uzi is a machine pistol popularized by the Israelis during the '67 war. It's the gun that's favored by various elite corps, including the U.S. Secret Service. Wonderful piece of machinery. I might say also, that when we do shoot, we are with a federally licensed firearms dealer who's licensed, and it's all perfectly legal. Although I'm not above breaking the law, you understand, but in this case … Usually we find a kindred spirit with a farm, and we fire our rounds into a hill―I've fired everything from a 30-caliber on down to 9mm luger, shotguns and pistols. We make a point of either shooting into the ground or into a hill, because these can travel as far as 20 miles. And we are working with live ammunition, armor-piercing ammunition. There are guys who go out into the Arizona desert and blow radio operated model airplanes out of the sky with 50 caliber machine guns. Helmer and I are envious of this, and may put together an expedition to join these armed aficionados in their casual fun.

GREEN: How do you like knives?

WILLIAMSON: I'm not really into knives. But that's strange, because I come from a Mexican Indian background, and you'd think I'd like a knife in my pocket.

GREEN: Would you like to see mine? [Laughter.]

WILLIAMSON: Let me see that blade, brother.

GREEN: No, well, actually, I was looking for a switchblade.

WILLIAMSON: Yeah, that's a nice one, nice lock-back knife. You can get switchblades in Mexico, but they're more difficult to smuggle in than pot. They've really cracked down on switchblades.

GREEN: Yeah, I had a beautiful one, but my wife took it.

WILLIAMSON: [Laughter.] Part of the settlement.

GREEN: You like to shoot guns, but it's different to shoot for fun and because you like it than to aim it at somebody, knowing you might scatter their brains, like that guy we saw last year. You want to tell about that?

WILLIAMSON: The last time Grass was in town, we were walking down Michigan Avenue, and some guy jumped off the Hancock Center and―

GREEN: Seventh floor.

WILLIAMSON: No, he jumped off the 90th floor. So he was pretty much scattered all over the sidewalk. He landed on his head and splattered all over Bonwit Teller's windows.

GREEN: You remember, the people were packed around us, so we stepped out into the street, and that dirty look that cop gave us―“You guys want to get back on the curb?”

WILLIAMSON: Surrounded by urban violence, the people were animated and excited like at a sporting event. These are the things cartoons are made of.

GREEN: That's right. A while back, you were talking about the Playboy Funnies and the first thing that entered my mind was, “Now that people will have read this, you can probably expect a batch of mail coming your way with all kinds of weird ideas, new stuff for the 'comics page'.”

WILLIAMSON: I would suggest that they not send it to me. I would prefer that they send their ideas directly to the cartoon office, 747 Third Ave, NYC. 10017. Send it to the attention of Michele Urry. It should go directly there, because otherwise I'll have to forward it, and that's an extra step. There's no sense in me being burdened by that. There's also no sense in the people who send it in being delayed by that much. The cartoon office claims that they're always looking for new ideas, although I haven't really seen anything new in that section for a while. One of the people I tried to get in this section early on was Wally Wood, and I talked to Wally. He was ready, he was willing to do it, and we submitted things, and they didn't bite on it.

GREEN: Oh, really? The way I understand it, he was pretty bad off health-wise, wasn't he? Alcoholic and a bad heart and cancer.

WILLIAMSON: He got some bad news, probably figured the best way out was just to snuff it. You know, there was an item in the newspaper yesterday that said that 47 percent of the population have suicidal thoughts. That's a lot of people. Of course you can ask, “Who took the survey? And who are they surveying?” But it seems fairly rampant, those feelings of despair.

GREEN: It's this high-pressure living system. You know, high inflation, high taxes, both husband and wife working, the kids are shunted off somewhere, you know. Make the money, make the money, and we're geared very high for cracking up.

WILLIAMSON: Then let's make cartoons and make people laugh! Why not? You got to do something. I tell you, when I was younger, I used to have, I don't think you'd call them suicidal thoughts, but morose thoughts. Since I've been professionally involved in my art, I don't even get bored. I don't understand people who get bored, it's beyond me, people who wrap themselves in their own ennui. You have to take it upon yourself to resolve your own problems. There's so much to do and so much to say, so many creative ways to express yourself, how can anyone actually be suffering from terminal tedium? I don't get it.

GREEN: Okay, now, see, maybe there are some people who are in a situation like me, I have so many ideas, so many things that I would like to do, and that I could do myself, except for lack of funds.

WILLIAMSON: We're all in the same situation, in a way. I may be a little bit better off in the sense that I'm nestled in the corporate womb of the Big Bunny, and I have enough of a name that I can go to people with a variety or projects without having the door slammed in my face. But I still have comic strips and ideas that I can't get published. I'm working on a film project that may never even happen because someone may not want to put up the loot. How unreasonable that someone won't part with three quarters of a million so I can make my movie. I think, honestly, just because you don't have the funds to do it, doesn't mean you can't go ahead and try to do it anyway. That was one of the important lessons of underground comix: A bunch of guys got together and said, “The comic book establishment's not going to let us publish because of the Comics Code, they're not going to let us do the kind of fantasies we want to put on paper, so we're just going to have to go out and do it ourselves, and sell them on the street corner.” And that's what happened. There needs to be more of that kind of spirit of “go out and do it,” and not be defeated by the obstacles because the obstacles are always going to be there, especially if you're on the creative edge. People are going to say, “You're crazy, man! I'm not going to publish what you're doing, this isn't funny, this isn't creative.”

I've run up against it time and time again. I've cartooned for every major newspaper in Chicago. I used to do cartoons for the old Chicago Today, editorial page cartoons, every Sunday. Chicago Today was owned by the Tribune Company. I was cartooning Spiro Agnew as the insidious buffoon he turned out to be. In the meantime, the Tribune was in Agnew's pocket, so I didn't last there very long. So much for freedom of the press. When you're dealing with a certain mindset, it's very difficult to penetrate it, but it can be done. It happens all the time. It's just a matter of keeping in there chipping away at the superstructure.

GREEN: And also, 1 think it's finding the right person at the right time.

WILLIAMSON: Partially. A good amount of reality, I think, has to do with where you are and who you know. Well, it's like anything else. Whoever you are, you're influencing people around you, and people around you are influencing you.

But the underground comix phenomenon didn't have much to do with who we knew. It had more to do with what we had to say.

GREEN: Okay, I understand what you're saying. I'm relating everything personally. I come from Fort Wayne. Nobody comes to Fort Wayne, and very few people leave. Paupers are left. Now Fort Wayne's dead.

WILLIAMSON: Thanks, Ronald Reagan.

GREEN: But I love Chicago. I love walking down the street with my portfolio, whether I've got work or not I just love being here, because I know this place, and art is all over.

WILLIAMSON: I came out of Canton, Missouri. If you think Fort Wayne's dead, just visit Canton. I'll tell you something about Chicago. Chicago is a secret that shouldn't be let out. New Yorkers equate

Chicago to Bulgaria. In L.A. the same distorted disposition reigns. I would just as soon people to continue to think that way. I wouldn't want them to discover it and destroy a good thing as they would. Chicago's the most livable of the big cities.

GREEN: Otherwise Frank Sinatra wouldn't keep coming back.

WILLIAMSON: Of course, Frank's got obligatory connections here too. The guys in the sharkskin suits.

GREEN: When I come into Chicago, talk to you, and then I go back, boom, man, I'm just swell up. I'm ready to draw, draw, draw, and I get back and start drawing, and then it poops out and I got to come back and refuel.

WILLIAMSON: One of the best things an artist can do is to talk to other artists. We have seven art directors here at Playboy. When we have our meetings, and we're working on an idea, the sparks can fly. You can sit around all day by yourself trying to think of a concept, but if you bounce ideas off of other creative people, it flows, it builds. I think you need the input of other people, generally speaking. There are those who work very well independently and are very reclusive about it. In my own case, I knew I was going to move to Chicago so that I could be with Jay Lynch because together, the ideas came. And Bijou was born. Then when the other cartoonists Crumb and Shelton and the rest would come to town, it was good for the old creative momentum, too.

GREEN: Well, just like last year, when you, Jay, Pat Daily, Suite, and I went to lunch. Now, that was probably, just kind of average, ordinary to you. But boy, you could tell by the way Pat was going to her it was really something. I was just thrilled to death. Here's five cartoonists walking down the street. Hey, boy, if a car came along, it couldn't hurt us, we'd just threw it off the street, you know?

WILLIAMSON: I've got a cartoon on my office door, here at Playboy. It's got this guy walking down the street with two women on each arm, and people look at him admiringly, and there's a cop pushing a blind man out of the way. The cop says, “Out of the way, a cartoonist is coming through!” That's a B. Kliban cartoon.

GREEN: One of the reasons that I'm glad to be here hanging out with cartoonists is the inspiration. Because for a while, I just got so disgusted that I didn't draw anything, for a long time, and that is horrible for a cartoonist.

WILLIAMSON: We all go through dry periods. We were talking about Shel Silverstein before and how he's got his fingers in so many pots. I've noticed this through him―when you have a variety of things to do, then you can go from one to the other, and switch back and forth, and alleviate that kind of dry problem. You can go from writing a story, to drawing a comic strip, to art directing, in my case, the film project, and it really helps if you have a broad base. There are paintings, too. that's therapeutic because if I've got nothing else to do, I can sit down and put 10 hours in on painting. So I've got a lot to keep me busy. I enjoy what I'm doing, and I continue to build my reputation. But it would be nice to really be independent, and work for myself only. In a way, I'm jealous of the guys who have done that, people like Crumb, who have been singleminded enough to say, “I'm not going to work for a corporation. I'm going to what I want to do. I'm going to determine my own destiny as much as possible.” But I've always been a worker in the sense that I don't mind working for and with other people. I enjoy the interaction. I'm not such an “Artiste” that I feel like I've sold out because someone's paying me a salary.

GREEN: You're a bit different from Jay in that he keeps a lot inside.

WILLIAMSON: He does and he doesn't. He tends to be a quiet person, but he's got a lot more going on in there. I think a lot of people realize the intelligence and abilities of Jay Lynch, but the way he realizes it is through his work, primarily. And then if you get to know him, he also opens up, he's got one of the great comedic minds I've ever met.

GREEN: Yeah. He kills me. He said that the reason that he didn't go for superheroes is because they're not real. Most of his collection of magazines and books deal with humor. He says he's not interested in super-heroes.

WILLIAMSON: That echoes my feeling. There was a period when Marvel tried to introduce a certain human quality, a reality. The first couple of issues of the Hulk, and the first Fantastic Four, and when Ditko was illustrating Dr. Strange. That kind of thing was pretty interesting.

GREEN: But then they overworked it.

WILLIAMSON: I think Stan Lee runs a factory. He's more a P.R. man than a cartoonist. I've watched Stan Lee and Harvey Kurtzman together on convention panels. Kurtzman is the artist and Stan Lee is the businessman and those realities show up in their work. Stan Lee is a rich man, but Kurtzman is rich in spirit. In terms of admiration, Kurtzman's got all of mine. I mentioned the history of Hefner that I'm working on. This constitutes a new direction for me. It has occurred to me that this would be a new way for me to produce comic art in a book format. It isn't really a comic-strip but there are as many cartoons per page as there are panels in a comic strip and the history aspect gives it chronology. It might be diverting to take it further. I could take any given situation, in this case it's Hugh Hefner and his life, but I could take anybody and produce an unauthorized biography or history―an illustrated history, by way of satire and parody. It's an intriguing form. It's similar to a sketch book report, which of course is nothing new. I started out doing single-panel gag cartoons when I was a kid. I didn't start writing and drawing comic strips until 1967 or so. Jay Lynch and I were corresponding while I was in college. He was a student at the Art Institute of Chicago and producing surrealistic, stream-of-consciousness comic strips. I was editing the literary magazine at Culver-Stockton College, and I got Jay into a couple of issues. Then we started jamming, doing the strips together. The attitude of these cartoons were kind of like early Bob Dylan lyrics, put to visuals. They didn't make a whole lot of sense, but we were excited enough to continue using the comic strip format. Leaf and Lung and Silent Celery were the titles of a couple of Jay's strips. He sent some copies to Salvador Dali, to get a second opinion on them, but I don't think Sal responded. Anyway it led us into underground comix. It could be that this illustrated historical pasquinade form could lead to excitement and transition, too. Of course, it takes a lot more research than comic strip writing usually does.

GREEN: You have to take the time to get the background.

WILLIAMSON: The background, and I've got to take the time to come up with a solid gag for most every panel. Comic strips are more like a flow, you start at one point and the action moves until you come to the resolution. In this case, each shot is a concept in itself. I like it. I've got an envelope sitting over here with 100 extra Hefner drawings in it. So if I take what'll be published and what's stashed away in the corner, I've got a considerable volume. The cardinal rule of cartooning is, “Never throw anything away,” because you can always come back to it, improve it, or resubmit it. I've taken ideas that I've submitted to Playboy Funnies, rejected ideas, reworked them a little or not at all and submitted them, and they're accepted. It happens. You never know if you're going to get to an editor on a bad day. I keep ideas, even if I just write down a sentence.

GREEN: Hey, I wanted to ask you―your little girl Molly, she's about two now?

WILLIAMSON: Two and a half.

GREEN: Note, do you want her to be an artist, a cartoonist like dad, or …?

WILLIAMSON: I want her to be a lawyer or a doctor or a C.P.A. so that she can support me in my old age. Her tendency now is to draw a lot. I'll sit down with her and she'll say, “Draw Daddy. Draw Mummy,” I'll do a quick drawing. Then I'll ask her to draw daddy and mummy. Because I draw, she does. I have another daughter, Megan, who's 15. She doesn't live with me, so she's not really oriented towards drawing, but she's creatively directed toward theater. She's an actress, and is pursuing it with fervor. She's got the same zeal that I had to be a cartoonist when I was her age. She's already got on-the-boards experience in community theater stage productions and is systematically pursuing all aspects of the performing arts. I don't know what the single-mindedness is, but there's a definite creative streak happening there even though we haven't lived together for a long time. My wife, Harriett Hiland, is a writer and a photographer. She is a journalist currently working for the New York Times on a regular basis, and as I said, she's a photographer, too, with a bunch of years at the Associated Press under her belt. So there's definitely what one could call a media atmosphere around our place. We both pursue our individual mania, and we have reached a certain level of aptitude. I'm sure that has to wear off on Molly, or definitely influence her in some manner.

GREEN: How old were you when you first started drawing?

WILLIAMSON: My earliest memories were that I wanted to draw cartoons. I would get in trouble when I was in grade school for drawing Mickey Mouse instead of doing my homework.

GREEN: But what is your earliest remembrance of drawing?

WILLIAMSON: My mother has a drawing I did when I was three or four years old. It's a crayon drawing of a monkey, and it has the tail. It's got a little hat on, and a little cup. It's an organ grinder's monkey, but I don't remember drawing it. People are very discouraging to kids who want to be cartoonists because they regard cartooning as a low form. I think it's an American folk art, it is the art of our times. It has been since Hearst newspapers started Publishing them and the first comic books came out, and now, of course, it's an international phenomenon. The Europeans respect cartooning more than Americans do, and in some respects, we have bigger reputations in Europe than we do in this country.

GREEN: Europe reveres everything about America more than we do.

WILLIAMSON: Jazz had to go to Europe because the musicians couldn't make a living here. My earliest recollection about cartoons was getting in trouble for drawing them. Then later on, when in art class I would draw, I would paint and everyone said, “That looks like a cartoon!” So I was coerced into making these things so they didn't look like cartoons. Finally I came to the realization that the reason I was drawing cartoons was because that's what I wanted to do. Of course, the early Mad comics were a big influence around that time. I would trace the drawings of Jack Davis, Will Elder, and Wally Wood. When I was in grade school and later in high school, there was a core of guys, there were three of us, and we were totally fanatic about Mad. We would sit around and try to out-Basil Wolverton each other. I'm the only one who became a cartoonist. One of that group is an artist, but he doesn't make a living at it, and the other one teaches music. But it was a good thing because here were three teenage jerks who were constantly competing with each other over who could draw the most outrageous bug-eyed monster. The input of other people can give the drive to keep going. And that drive took me to a certain point. The point where I finally got a cartoon published, in Help! magazine. That gave me the impetus to go further. After that first cartoon, it was two more years before I got another one published in that or any magazine. And I was sending batches every week, 10 or 12 cartoons a week. And I'm talking really bad cartoons.

GREEN: Ah, the good days when postage was cheap.

WILLIAMSON: Yeah. But I wasn't discouraged in this foolhardy pursuit by my parents. I grew up in a liberal family. My dad was a professor, and he never said, “Ah don't want mah son to be an artist, he can't make no money doing that.” I think in his heart of liberal hearts, he didn't mind me being an artist and he figured I'd outgrow this cartooning thing.

GREEN: I think if your parents were like most parents, especially in today's time of drug-oriented youth, they were glad to know what you were doing, instead of you being out running the streets, and they don't know where you're at.

WILLIAMSON: Aw, I was out running in the streets, too. I think most of us go through a certain stage where we drive our parents totally nuts. But the thing is, as I got older, I got more and more into my cartooning and so I tended to stay home more than running the streets with the guys. I wasn't aimless. I had a focus.

I had some fun with the guys, too. My dad had to haul me out of a pool hall once, he was all upset that I was hanging out in a pool hall.

GREEN: Oh, I'm not saying that I was the perfect kid. I got beat before the word child abuse became just a national household word. My father whipped me with everything from ironing cords to leather straps, to belts.

WILLIAMSON: That was the style of the time. Now, you can't do that and remain respectable―not that child abuse ever deserved respect. That was the disciplinarian style that came out of the depression. Everyone came back from fighting the Nazis and the Nips, and they had discipline. What this kid needs is discipline. And they would give it to him, they would give it to me, they gave it to you, they gave it to everybody. Look out! Whap! Ow! That was the style of the culture. We're a little more understanding now, and most people don't believe in that kind of daily violence.

GREEN: But it's too easy. That's why Dr. Spock said, “Don't whip your child” and now, 20 years later, he says, “I admit I was wrong, we have raised a nation of selfish bastards.”

WILLIAMSON: The nation has always been a bunch of selfish bastards. It isn't because we didn't beat our kids. The people haven't changed, the culture has. It's the same collection of self-serving scumbags as ever. People talk about the Holocaust, and talk about the murder of six million at the hands of Hitler, but we totally eliminated the Native Americans as a race. Genocide is genocide. It's been happening since we clawed our way out of the primordial ooze. Man did not evolve from monkeys. Monkeys are a fun-loving group of vegetarians. Man evolved from small, intelligent rodents. Our ancestors were rats. Rats bit babies and spread plague. I'm absolutely certain that we are destined to become extinct by our own hand. Throughout civilization, the fortunes of the few have been built on the bones of the many. And this is the truth. I don't think that our generation represents the lowlife meatbag aspect of humanity any more than previous generations. Perhaps we're even a little more enlightened because of television. It was rough during the Middle Ages. There were no rights. They could cut you down and serve you up. It wasn't that long ago that stealing a loaf of bread was a capital offense.

GREEN: The only thing that keeps coming back to my mind is that today's kids, although they're more bored than any other generation, I think, they have more. Naturally, because the world is progressing, but when I was a kid, I had a little pedal car, pedaled my damn legs and feet off to get around the corner. These kids nowadays―

WILLIAMSON: They put it in overdrive, and take off. But every generation complains about the same thing. “Well, Ace, when I was a kid, life was terrible torment. And kids these days, they got everything.” But that's the march of civilization. That's the commercial society, the legacy of the industrial revolution.

GREEN: But that's money.

WILLIAMSON: It's the American way, isn't it?

GREEN: Now, your major influence is the same as mine―the Mad group.

WILLIAMSON: Some other people, too.

GREEN: But I mean prior to that, from your early life on through.

WILLIAMSON: Walt Disney was the first major early influence that I can remember. Of course, Snow White came out before I was born, but as soon as I could see, Snow White, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, Uncle Walt ran it. Disney was probably, culturally, the most important influence on the country at a certain formative period because he caught all the baby-boomers. He caught all the little rug rats like you and me, and he twisted our minds into a never-never land mindset.

GREEN: Not only that, but even though it had Walt Disney's name on it even as a youngster I recognized the different styles in the drawing, and certain ones appealed to me.

WILLIAMSON: One of the good things about Disney was that he put all those wonderful German and Teutonic illustrators to work. He hired the best people, which was wonderful in terms of style. Unfortunately, he chose to become homogenized and politically he was reactionary. But his early work was excellent, and I think that was kind of the hallmark for the generation. The Sunday Funnies were a big influence in those days, too. I was named after a comic strip character. My grandparents nicknamed me Skippy after the Percy Crosby comic strip character, Skippy. So, it seems almost that I would end up scratching out a living doing this. The focus came very early. It was almost out of my hands, and that's not a negative.

GREEN: That's most definitely a positive. Especially if you think about it in that positive manner. But, I'm confused. Fandom has given me the nickname of “Grass Green.” Now, does that mean that pretty soon I'm going to go on pot? Because I've never smoked pot in my life.

WILLIAMSON: Oh, you're the one. I knew there was somebody.

GREEN: What is your favorite reading other than cartoon-related items? Jay likes humor, but he reads some deep stuff.

WILLIAMSON: I don't read a lot of novels. I read a lot of magazines, and pay attention to media, because of the business that I'm in. I'm not one to devour a tome. I'll seldom read a thick, heavy book. I find that I get bogged down and I never get back to it.

GREEN: Something light and breezy, hopefully.

WILLIAMSON: It's not that so much. I pick up a lot of information. I read manuscripts all the time. They come across my desk every day, so I read the best authors and what they're writing. It's just that I don't read huge volumes. I read a lot of information. I read the New York Times, I read all the newspapers. I read all kinds of periodicals. I'm not really a reader of books.

GREEN: You mean Mickey Spillane, Ernest Haycocks, stuff like that?

WILLIAMSON: Mickey Spillane I like. Mike Hammer's wonderful. Mickey Spillane is basically a cartoonist. He's a practitioner of the vulgar arts, like a cartoonist or filmmaker. There's a great parallel between film and cartooning, and cartooning and film. Fellini was a cartoonist. Panel-to-panel, structuring of a scene is like a storyboard. And that's the basis of all film work. Creating a scene, a plot, a pattern, and following it through to resolution. So there is definitely an affinity. If you look at Will Eisner, in the Spirit, you see a lot of the influence of Eisner. In Film Noir the influence is obvious down to the lighting and the angles, it's amazing.

GREEN: When you mentioned storyboards, I'm reminded of when Jerry Lewis was popular. He was known for being able to conduct an orchestra very well. Then they showed us how he did it. He storyboarded the whole thing. He had his signals written down as to what he wanted the guys to do and they would do it.

WILLIAMSON: The best storyboarder of our time is Harvey Kurtzman. He has a real cinematic sense. I don't know why he never went into filmmaking. It's our loss that he didn't. The man who's picked up on that cinematic flair in the undergrounds is Gilbert Shelton. He uses the same sort of systematic storyboarding. He gives a humorous time sequenced set-up, just in the visuals alone. It's very sophisticated. I also have the suspicion that it's not planned out so much as it occurs intuitively. Hence my interest in film. Cartooning to film is a natural transmutation. I think I'm also intrigued by video. What I like is the small screen, because the small screen is like a panel. It's not an enormous image in a dark room that becomes your world. The video screen is the panel, and the approach to video would not be as detailed, as much as it should be color and character. Did you see the film Alien?

GREEN: Yeah.

WILLIAMSON: Alien was a very dense, dark and detailed movie. I saw Alien in the theater and I liked it, but when I saw it on videotape, I couldn't see what the hell was going on. But if you take video and use it the way it should be used, with more simplicity, I think it's a whole other form. You're dealing with a less dense quality. It's more direct, almost a more cartoon style, which is, I think, the best video.

GREEN: Well, when you know that you're dealing with a more limited medium, space-wise, you're talking about compaction. And so, you would tend to eliminate a lot of detail that would actually detract from the message.

WILLIAMSON: Sometimes the sense of reality is lost. For instance, the Muppets work well on TV, but when they made the transition to the big screen they didn't look real anymore. They are a small-screen item. When I was a kid, I saw The Wizard of Oz and loved it. But I saw it recently on a big screen, and I could see the wire holding up the Cowardly Lion's tail. The reality went right out of the window. On television, it still looks wonderful, because the small screen hides imperfections.

GREEN: Yeah, one of my big disappointments about the movies when I was a kid and saw Francis the Talking Mule I thought, “My God! They've really got a talking mule.” But then, in a couple of scenes, they had the camera at a wrong angle and you could see there was a wire on his mouth, and they were jerking it.

WILLIAMSON: Your sense of reality was betrayed. It's like when somebody told you there wasn't any Santa Claus. Want to know how I found out that there was no Santa Claus? From reading a comic strip. The Blondie comic strip in the Sunday Funnies when I was a kid. Dagwood and Blondie were trying to figure out how they could convince Cookie that there was a Santa Claus. So, essentially, they were saying there wasn't one. Comic strips and cartoons have held great weight in my life. My earliest recollection of film was having the shit scared out of me by a Bugs Bunny cartoon. In it, Bugs Bunny goes to Hell, and my mother had to take me out of the theater because I was terrified. The Warner Bros. post-war cartoons were great. Better than Disney because of their sense of insanity. We can talk for hours about animated cartoons.

GREEN: I was going to ask you―are you pretty heavily into animation? Have you done any animation projects?

WILLIAMSON: No, I haven't. People are constantly asking if I've done any animation. My style would lend itself to animation because it's so broad. The problem with animation is the cost. So if I was going to do animation, I'd need to have to have a studio of animators. Otherwise, I'd have to spend six months out of my life doing it; meanwhile, who'd pay the rent? I'm in a position now, maybe through this film or through a couple of other routes that I can eventually do a piece of animation. It would be fine with me. But I need a studio, and I need to be able to supervise it with an iron fist. I would have strict creative demands.

GREEN: The reason I asked you that was because I think that with your style, with you at the helm, you could probably turn out one of the funniest films. I saw one cartoon where there was an ugly princess. She laughed, and her mouth dropped over halfway down the screen. Man, I roared. I almost fell out of my seat, because you don't see that. Everything is usually minimal exaggeration but cartoons are supposed to be exaggeration.

WILLIAMSON: Exaggeration is the key. You need somebody to do wonderful voices. You need a Mel Blanc. You can even work with a limited animated style like Terry Gilliam did for Monty Python. He used the limitations to his advantage and did it well. Now Gilliam's directing film. He directed Time Bandits and he has one almost in the can called Brazil. With Bullwinkle, Jay Ward used the limitations of his budget to the best advantage. Bullwinkle was funny because they had good voices. They had wonderfully deranged scripts that appealed both to kids and adults. They had exaggeration. Hanna-Barbera uses jerky limited animation. But there's nothing funny happening.

I think eventually animation will come to me. The circumstances have to be right. And you've got to have a market for it. I mean, where are you going to market these things? I've also been thinking in terms of puppets. One of the guys I'm working with on this film project is wonderful at doing little puppet monsters. As a matter of fact, he has a puppet show on film. It's something like Uncle Ned's Puppet Theatre. Uncle Ned is a janitor at Genetic Laboratories, and there are these little mutant puppets, genetic mistakes. They let them out of the cage, and they have to come out and clean up after business hours. One of them is named Gristle, and one of them is named Hook. Gristle steals Hook's pet rat-tail, so Hook gets out a chainsaw and saws Gristle in half. It's wonderful. Blood is spurting all over the glass. There are a lot of ways to go. You could do a show like the Muppets, make it adult humor, make it sexy or sick or whatever.

GREEN: I don't think it's been done.

WILLIAMSON: Everything's been done, so I wouldn't be surprised. But I haven't done it yet. There are so many projects that there's no time to do them. How could a person possibly be bored when there's so much to be done?

GREEN: I don't think I get depressed from boredom. I get depressed from either lack of inspiration or time. Having too much to do, I don't know what to do. So I'll go watch TV, get my mind off of it, and then, slowly, some priority will come up. “I don't know, I'll do this.” I'll get up and leave the TV. And that's rare because I am a TV addict. I watch commercials, cruddy commercials I've seen before. I'll sit there and cuss at them, but I'll watch them. I am a TV addict.

WILLIAMSON: I am too. I consume large amounts of TV. Chicago doesn't have cable TV. It's one of the last cities in the country not to have cable. But I just moved out to Oak Park, and I got cable. And I am in heaven, man. I'm watching all the time. Even when I work, I have the TV on as a background noise. Like the Great White Hope, it's the great white noise. I don't have to pay attention to it, but I can still absorb it. I can draw, whereas if I'm listening to music, it diverts me. I have to listen. Television is another great vulgar art form, like jazz, like movies, like cartoons. Liberal snobs enjoy putting down television as being without worth when it's really the liberal snobs who are without worth. The potential for TV is absolutely amazing. The form itself is innately educational, it's informative, it's immediate, it's in your own home.

GREEN: But it's run by those in power who are money-hungry.

WILLIAMSON: I have faith that those bozos will go belly up due to their own lack of vision. Because what's happening is every year networks are losing more and more viewers to cable, where there's more flexibility. The future is in cable, pay-TV, and public access. It's very embryonic at this point. Cable and pay-TV are mainly showing movies, and rock videos.

Programming is beginning to happen. Actual producing is beginning to happen. The reason that's beginning to happen is because so many viewers are switching over. And that's part of the reason I'd like to be involved. There are similarities to the early underground comics movement. You go out and do it. There are differences. You really have the opportunity now to just go do it, to put together a script, even if you can't sell it to like HBO or Showtime, or the Playboy Channel. There's always public access. Public access is free time. Take your script and your friends, and stand in front of the camera, and do it.

You know, there are some very funny things on cable. Canadian broadcasting through the Canadian film board has a lot of animated shorts, and there are experimental concepts broadcast, some of which are boring, but some of which are very interesting. Experimentation is happening, at least in between the movies.

GREEN: I wager that as a cartoonist if you were to go to Europe, you could almost call your own shots. The reason I say that is because somebody like B.B. King ran around America most of his life, got the term King of the Blues, but is still recognized only by the black people. But he goes over to Europe, man, they eat him up, they keep him over there five or six years. He wants to come home, and they don't want to let him go because they think he's fantastic.

WILLIAMSON: In 1963, me and my friends used to go down to East St. Louis to hear B.B. King playing at the Red Top or at the Paramount Club underneath the railroad tracks in East St. Louis. Nobody knew about him except the blacks. It was a wonderful time. A couple of young white boys hanging out where they shouldn't be. But it was fun. The times were different then, though. There wasn't nearly as much hostility as now.

GREEN: You think there's more hostility now!

WILLIAMSON: I think so. See, I could cruise with the people. We'd buy some wine, we'd get some reefer, we'd go over and spend all night long, until dawn listening to electric blues. You know why? Because of the early civil rights movement. There was affection for people who were trying to cross over and appreciate another's culture. Since then, the lot of most black people, and this also goes for latinos and other minorities as well, has been improved so little, that there's a lot more hostility toward the whites and for good reason.