Introduction

University of Washington professor José Alaniz invited me to prepare and deliver a guest lecture on early comics for his class on food-themed comics. I hoped the project would turn out to be something I could really sink my teeth into. I was not disappointed.

Eventually, over half of this material developed for this lecture was cut, in order to fit the 45-minute allotment of time. I’ve restored the presentation and offer here a “director’s cut” with my own audio narration, packaged into a video that runs for about an hour and half. I hope you find this to be a tasty and nurturing repast.

The Lecture

Additional Notes

When you think about it, food is a pretty ingenious topic for studying a popular art form. Eating is something we all do; it’s woven throughout cultures and histories. Viewing comics through the lens of something so ubiquitous and essential reveals a “living art” aspect to the medium. For example, an E.C. Segar 1933 Thimble Theatre Starring Popeye comic strip in which Wimpy salivates copiously over a juicy hamburger is something a reader in 2017 America can directly relate to because that food is still a part of our culture today. Wimpy would not be amusing today if his ardent passion for a hamburger with “pickles, lettuce and onions both” were instead, say, dancing the Lindy Hop. Because of its universality and direct route to our brains, hardwired to crave and consume edibles every day, food as a theme can help make a comic strip relevant to succeeding generations.

Aside from the timeless aspect, broadly surveying food themes in comics from 1865 to 1954 reveals a fascinating correlation with social movements, trends and history itself. For example, comics in the mid-1940s depicted wartime food shortages and ten years later, they skewered excessive consumerism, mirroring America’s own changes through World War Two and into the prosperous 1950s. Comics, it seems, have often reflected the times in which they were made. The great comics both reflect and comment upon the times, all the while entertaining us.

José Alaniz (Death, Disability, and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond), who develops and teaches a comics studies curriculum at the University of Washington in Seattle, has prepared an entire course on food in comics. The introduction to the course reads, in part: “We will sample classic and recent comics works from around the world devoted to food: growing it, making it, slaughtering it, preparing it, dressing it, serving it, obsessing over it, and, of course, eating it. Discussions and lecture will cover such related matters and economics, agriculture, service work, food disorders and cross-cultural cuisine …”

The texts for this course include Oishinbo: Japanese Cuisine: A la Carte by Tetsu Kariya (2009, VIZ Media LLC), New York Times bestseller Relish: My Life in the Kitchen by Lucy Knisley (2013, First Second), and Over Easy by Mimi Pond (2014, Drawn and Quarterly). The course looks at a number of comics from Winsor McCay to E.C. Comics and beyond.

Chronomethodology

At first, the concern about developing my guest lecture was whether enough examples of food in comics could be found to fill the allotted 45 minutes. After a few days of work, the problem shifted to culling out the best of the many, many comics that either were food-centric in concept, or had notable “food moments.” A search on the Grand Comics Database for the keyword “food” alone yields 2,762 results―and this database does not include newspaper comic strips, only comic book stories. Holy Moley!―as the Big Red, um, Cheese might say.

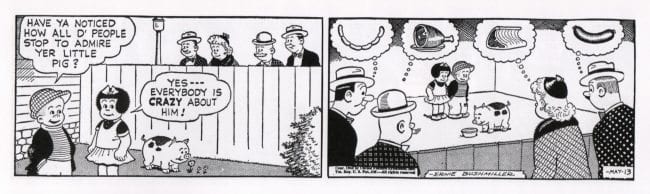

In refining the selection to be presented, the obvious first picks would include iconic examples of food in American newspaper comic strips that were created prior to 1950, and which influenced American appetites and businesses. These include Jiggs’ obsession with corned beef and cabbage in Bringing Up Father, Dagwood’s vertiginous everything-but-the-kitchen-sink sandwiches in Blondie, and in Thimble Theatre Starring Popeye there is Wimpy’s hamburger obsession and Popeye’s spinach (mostly a byproduct of the Fleischer Brothers Studio animated cartoons). Interestingly, as I researched Blondie, I learned about Dagwood’s four week hunger strike to be allowed to marry Blondie, and decided to include that, as well, for contrast.

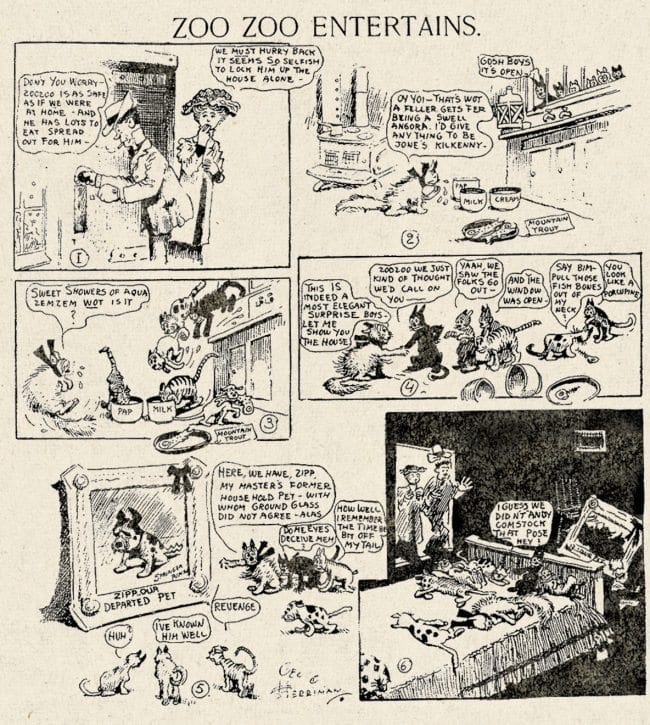

Beyond the obvious choices listed above, my final selection included comics from the 1865 Wilhelm Busch classic, Max and Moritz, linked to the The Katzenjammer Kids by Rudolph Dirks. Next comes Richard Outcault, who began his career in comics with sad, quasi-journalistic cartoons of hungry New York back alley kids and quickly shifted, with fame and widespread acceptance, to the joyful screwball chaos of the goofy Yellow Kid comics. I also gravitated toward the master stylist, Lyonel Feininger, who brilliantly created the artful Kin-der-Kids, a “kid” comic page featuring the nightmarish obsessive eater, Pie-Mouth (a forerunner of Augustus Gloop in Roald Dahl's Charlie and The Chocolate Factory). Themes that emerged from the presentation of these classic comics through this lens included depictions of the disenfranchised and the dangers of rampant consumerism, driven home with the bloody four-color newsprint slaughter of a whale, who asks with his dying breath, “Who would have think it?”

I was fortunate enough to stumble on Hungry Henrietta, a little-known 1904 series by Winsor McCay, most famous for Little Nemo In Slumberland. This is a highly innovative series for several aspects, not the least of which is the strip’s step-by-step depiction of the emotional origins of an eating disorder. Probably the best slide I made in this presentation shows 21 images of Henrietta, one from each episode. The chronological sequence reveals her weight gain, subtly handled in stark contrast to the dramatic verve with which McCay depicted physical transformations in Rarebit and Nemo. Look closely, and Henrietta's heartbreaking disaffection with the world is also charted in this display.

Since the American comic book got rolling in the late 1930s, I had the first years of that medium to explore, as well. I decided to show a story from an obscure early 1940s series, The Face – in which the hero has no superpower and simply dons a Halloween mask to fight crime. In the story shown, he is morally outraged when a crooked businessman sells spoiled meat to an orphanage. Ultimately, the food becomes a symbol for what’s wrong with society. Oddly, I looked, but didn’t find any notable examples of food themes in Superman or Batman stories from the 1940s. Surely, there are some out there. I did find some examples of comics dealing with wartime food shortages, including a lovely Simon and Kirby Sandman story.

Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder’s classic Mad story, “Restaurant!” addresses the shift from wartime shortages to overabundance and mad consumption. The more sophisticated themes and treatments reflect the maturing of the form, as well as the genius of Harvey Kurtzman. The story shows us the reality in the kitchen of our favorite restaurant, and it’s not pretty. Also from the publishers of Mad, E.C. Comics, there is the classic horror story – also drawn by Jack Davis – Tain’t the Meat, It’s the Humanity in which a hacked up human carcass is sold as meat in a butcher’s shop. We’re a long way from the gentle melancholy of Outcault’s kids.

Reed Crandall and Mike Peppe’s “Corpse That Came to Dinner” seemed ideal for the lecture, as well. It’s a vicious skewering of idealized coupling in 1950s middle class America. Wholesome comics also carried hidden social commentaries, especially when they were about food. John Stanley and Irving Tripp’s “Frog Legs” from a 1950 issue of Little Lulu again deals with issues of society and class and, surprisingly, the larger dilemma of sorting out when a creature is a cute animal, and when it is a “delicacy.”

The presentation ends with a look at the 1949 Donald Duck adventure, "Lost in the Andes," by Carl Barks. Some, myself included, regard this to be one of the greatest comic book stories of all time. This is the famous square egg story and it prefigures the desires of capitalists to remake nature for a profit, foreshadowing today's genetically modified food products.

Stepping back to examine this flow, it became clear the selections, when considered in the order on which they were created, presents a poor man’s history of comics, showing the development of the form from Wilhelm Busch's 1865 sequential images through the development of the American newspaper comic strip and to the first decade or so of the American comic book .

Selected Outtakes

Alternate Structure

Instead of a chronology, a thematic structure was briefly considered. Since the lecture was to be given to college students who probably lacked an overall understanding of comics history and who might become confused with a non-linear approach, this structure was discarded.

The Hungry, Homeless and Disenfranchised

Max and Moritz

Katzenjammer Kids

Outcault

The Face

Simon and Kirby Sandman story

Voracious Appettites

Feininger’s Pie-Mouth

Segar’s Wimpy

Jiggs – Irish foods

Dagwood sandwich

Lulu/Frog’s Legs

Food Dreams and Nightmares

McCay’s Dreams and Henrietta

Mad: Restaurant!/ Supermarket!

Tain’t the Meat

Corpse that Came to Dinner

Lost in the Andes (nightmare of altering food source)

+++++++

Paul Tumey is a writer, artist, and designer who lives in Seattle, Washington. He is available for projects, lectures, classes, and curating and would love to hear from anyone interested. He has run his own presentation design business, Presentation Tree, since 1999. His comics history work appears in THE ART OF RUBE GOLDBERG (Abrams ComicArts, 2013), THE BUNGLE FAMILY 1930 (IDW, 2014), SOCIETY IS NIX (Sunday Press, 2013), KING OF THE COMICS: ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF KING FEATURES SYNDICATE (IDW 2015). Most recently, Tumey has written for the Sunday Press DICK TRACY collection as well as the forthcoming book on Rube Goldberg, due out in May 2017. He is currently at work writing a book about the great American screwball cartoonists.