The website of Study Group Comic Books has a button on their menu bar labeled "Genres." It speaks volumes about the publishing mission of Zack Soto—the choices range from familiar genres like "Fantasy," "Horror," and "Crime" to "Abstractions" and "Trippy." No alternative comics publisher is as explicit in its interest in genre comics as Study Group, both on the website and in paper form. Soto is also the rare publisher that still releases single-issue comics as part of a larger series as opposed to focusing on full-length books. Soto exhibits a voracious appetite for absorbing and understanding comics of all kinds, and that's also reflected in the Study Group Magazine that he publishes with editor Milo George and art director Francois Vigneault.

Study Group is far from the only alternative comics publisher that deals with genre, but they focus on it more than any other. That said, their output look less like the sort of genre comics one might see from larger publishers and more like the kind of gritty, idiosyncratic comics associated with minicomics scenes like Providence in the late 1990s. Manga and other genre influences like EC horror comics can be widely seen in some Study Group releases. Let's take a look at their output from the last couple of years.

Titan #1-5, by Francois Vigneault. This is a smart, stylish, political sci-fi romance thriller. In the future, gigantic, genetically modified humans called Titans work in mines on various moons around the solar system. They are a labor class that works for Terrans, who are their managers and security force (and essentially, represent a higher caste in a hierarchical system). The story centers around Joao Da Silva, a Brazilian manager sent from Earth to evaluate the Homestead station on Titan, and Phoebe Mackintosh, a Titan labor representative who is tasked to monitor him. There are multiple intrigues on both sides, with the tension between the Titans (who work in hazardous conditions) and Terrans (who are viewed as exploiters) being cynically stoked by several individuals with selfish agendas. Vigneault makes the story work because of the intense characterizations of Joao and Phoebe. They have conflicting agendas prior to meeting, but their immediate sexual chemistry alters the course of the story.

Obviously, issues of class and race inform the central conflict of the story, but mostly in a way that drives the plot instead of as a sort of transparent, heavy-handed Star Trek-style moral metaphor. Instead, the comic more closely resembles another science-fiction TV show in terms of tone and moral complexity: the revamped Battlestar Galactica show from the '00s. Titan has the same lived-in, grimy feel; living in a space colony is cramped, sweaty and unpleasant. There are the same sorts of secret deals, hidden agendas, double-crosses, and acts of violence that spark huge amounts of unrest. There's also the same emphasis on romance as a kind of frenzied, desperate activity that is literally life-affirming in the face of danger. Both Joao and Phoebe are smart, centered, funny and ultimately moral character.

Vigneault is a skilled cartoonist and his character design and attention to detail emphasize the claustrophobic character of the colony. His faces, interestingly enough, have a cartoony & exaggerated character instead of the more naturalistic technique he uses for the rest of his drawings. Vigneault favors thick eyebrows, lots of dripping sweat, and dense scars. The reader is welcomed to crawl inside every panel and take a close look, as Vigneault rewards close reading with all sorts of interesting detail. Each of the five issues has used a different color wash, with the third issue's red being especially fitting for an extended sex scene.

This is a solid example of genre fiction that doesn't insult the reader's intelligence and has multiple layers, but doesn't try to thematically overreach. Both sides in the conflict have their own ethical murkiness, but Vigneault is more interested in developing how that affects conflict, action, and character interaction than he is in lecturing the reader. The final issue takes a number of unexpected and brutal turns, but the romantic element of the story is far from ignored.

Power Button #0, by Zack Soto. Genre-inspired stories told in an idiosyncratic narrative and visual style, Soto's comics seem to be very much influenced by Fort Thunder. Unlike his stylish and innovative Secret Voice comics, this story feels remarkably derivative of old Marvel titles like The Silver Surfer and Rom, wherein a brave person from a world threatened by overwhelming outside forces sacrifices themselves. That sacrifice comes by way of undergoing a transformation that allows them to save their planet but permanently separates them from further contact. This comic looks nice but is otherwise quite conventional, which is disappointing considering the quality of Soto's other work.

The Secret Voice #1-3, by Zack Soto. Soto is strongly influenced by Mat Brinkman and Brian Ralph, and that influence is most clearly evident in the first issue of this continuing series that's jammed full of clever ideas, appealing world-building, unusual and eye-catching character design, and an idiosyncratic use of color. This is a fantasy epic about a nearly invincible warlord and the enigmatic scholar-sorcerers in the Red College who oppose him. Soto is all about establishing place and letting the reader absorb its particular rhythms; the opening of the first issue features several pages following a water source down deep under a mountain until we meet the main character, a bandaged and bespectacled Red College member named Dr. Galapagos.

What I like best about this comic is the way that Soto balances one narrative with several others that jump back and forth in time, creating a one-man anthology similar to the sort of fractured storytelling that Lewis Trondheim and Joann Sfar do in their Dungeon series. Soto even varies his visual approach in these interstitial features, going from the denseness of his "Secret Voice" serial to the airy and open layout of "Heard You Were Around", where Soto almost entirely abandons line in favor of color and shape. It's not quite abstract, but the looseness of the art fits the wistful and nostalgic quality of the story.

The "Secret Voice" story in the second issue is not nearly as reminiscent of Fort Thunder. Soto expands his world-building and central character conflicts to reveal that Dr. Galapagos is tormented by a voice that possesses him at times, and the reader meets other Red College members who are fighting the war in their own ways. The scope here is not unlike Lord of the Rings: vast battles, cities under siege, huge armies of monsters, and a desperate defense. The structure of the heroes' society is unusual enough to make this story happily free of cliche, and Soto's use of restraint in giving the reader just enough information to follow the story without overwhelming her with backstory lends the story a mysterious but appealing edge. Of course, given the more conventional narrative structure in the main story, Soto throws a more enigmatic narrative at the reader in the backup serial, "Maps Of The Unknown World", which is once again all about space, environments, and slowly illuminating them.

One can see this series as Soto experimenting with and finding his stride as a cartoonist. The third issue is more visually complex but also more original than the first two issues, as his own style starts to emerge. There's an effortless flip between the main plot and nuanced character interaction. What's remarkable is how quickly the comic proceeds despite being a relatively peaceful interlude in the larger story. Soto makes up for that with another time-jumping feature with a dark, denser and scratchy approach that is built on deep reds and purples (and drawn by Jason Fischer), and a narrative that is relaxed in its pacing even as its actions (keeping demons from entering a gate) are frantic. The second installment of "Maps Of The Unknown World" is suitably enigmatic, but there's a bit more context added to make the narrative more coherent, even if its connection to the larger story remains unclear. Soto is the pacesetter for the Study Group line in many ways; his fusion of genre tropes and alt-comics storytelling has been the model for this kind of comic for quite some time.

Magical Character Rabbit, by Kinoko Evans. This is self-conscious shojo manga, down to the funny "translation" in the title and the characters underneath it. It's a relentlessly cute but still interesting story about a rabbit wizard who is tasked with performing the town's winter solstice rite. On cheap paper that handles the deeply saturated colors well, the comic is basically about the mage's attempt at figuring out what she has to do in order to perform the rite. Evans knows how to pace a comic and this one is no exception, as the rabbit runs into a variety of characters--some helpful, some annoying--while trying to figure out just what to do. The purple, orange, and yellow color scheme varies in that some colors look like they were done on a risograph and others look like they were hand-colored via colored pencil. This is a perfect comic for a child aged 8 through 12. A knowing fan can enjoy the tropes that Evans runs through, while a young fan can enjoy it purely on its own terms. Evans' use of a thick line sets it apart from a lot of manga-style stories and gives it a solidity unusual in comics that strive for cuteness. It makes the village and its characters seem more mundane and less ethereal.

The Short Con, by Pete Toms & Aleks Sennwald. This attractive book, done in small, square format, is another Study Group release aimed at children. The high concept is very funny: the residents of an orphanage also happen to run a detective squad that solves all sorts of crimes. The book fits somewhere between Richard Sala and Drew Weing, combining the weird, the creepy, the absurd, and the adorable all in one package. When a rich girl is sent to the orphanage, she's paired up with the slightly misanthropic girl nicknamed "Pops," who has a habit of accidentally getting her partners killed. Toms exploits every cop trope one can think of, and while the identity of the killer is completely ridiculous, it makes sense within the context of the story. Working mostly in a four-panel grid, Sennwald takes a lot of cues from Sala in terms of character design, only he uses a slightly thinner line and deliberately makes the characters look they're playing dress-up. Only in the context of the story, danger is everywhere, be it from robot dogs or the machinations of a master criminal. The pacing of the book is spot-on, allowing just enough character growth and bonding without padding it too much. Everything from design to coloring is top notch on this little book, and I found myself wanting.

Vile 1-2, by Tyler Landry. These are short, moody horror stories that rely on atmosphere and suggestion instead of gore. Each issue uses a single spot color to go with the black pages; the first issue features light green and the second issue dark green. There's some classic EC horror comics influence here, but only up to a point, as Landry deliberately employs vagueness as a storytelling tool. For example, the first issue starts with an interstellar battle where the "good guys" seem to be winning, until one ship is shot down and crash-lands on a planet. Up until that point, we have no reason to believe he's anything other than a laser-toting hero. When he crashes and sees what might be the skeletons of former crewmates who were left on the planet as expendables when they crashed earlier, the reader is clued in that this guy is a narcissist and a sociopath, and possibly delusional to boot. What Landry leaves vague is if what the pilot sees is real or just a hallucination. In the end, it doesn't matter, because the reader sees him for what he really is.

The second issue is a typical "someone goes missing in the forest at night" story that's set up in the first segment by the two main characters looking for gold, talking about how important companionship is out in the wild. As soon as the emotional depth of that point is developed--boom. The younger character simply disappears. The older character thinks he sees his friend's skeleton for a moment, then follows his trail to the river, where the younger man's half-eaten apple has been abandoned. He is not discovered, nor is any explanation given. Nor is it necessary; the story is about a feeling writ large, with the terror of loneliness and the unknown holding full sway. Both issues are well done but feel on the thin side as complete products; I'd prefer to read a larger collection of these stories.

Haunter, by Sam Alden. Alden is in an interesting phase of his career at the moment, experimenting with a number of visual approaches in order to tell different kinds of stories. He's gone from the heavily naturalistic style à la Nate Powell to an almost abstracted pencil-heavy style that emphasizes shading as a way of creating form. Figures are created as a kind of negative space. Alden has always been fascinated by the idea of exploring ruins and other places people shouldn't go, and the consequences of those actions bringing on horrific ends or bizarre consequences. In Haunter, Alden takes up that theme and applies a vivid, often nightmarish color scheme through the use of watercolors. Watercolors sometimes bleed and saturate the page in funny ways, and all of that works to Alden's advantage in this comic.

In terms of narrative, it's sort of Josh Simmons meets Carl Barks. That is, it has the relentlessly fluid panel-to-panel transitions that makes it a thrill ride to read, along with the silent qualities of key Simmons works that inspire dread and a sense of impending, inevitable doom. The story is simple: a young woman is hunting a boar-like creature with her bow and arrows. After missing and tracking her prey, she discovers an abandoned temple of some kind, flooded in a number of areas. Eventually, she finds a huge statue of some sort of god-figure and sees a tunnel in the middle of it. She goes down the tunnel until she encounters a tall, monstrous guardian that immediately starts shooting at her with its own bow. The rest of the comic consists of the hunter's attempt at escape and the guardian's attempt to kill her. The way Alden shifts from green to yellow to blue to purple and to orange as a way of reflecting fading light and other visual illusions while also mixing in other colors to create dissonance is truly the story of this comic.

Though Alden's linework is greatly muted by the color splashes in this comic, it's still remarkably precise and effective, especially with regard to the two figures. We feel the hunter's curiosity and later desperation, thanks to the way Alden draws body language as well as the line weight giving the character real presence. The guardian, a terrifying mass of spikes and thorns, has a line weight precisely equal to that of the hunter. That's a subtle way of indicating that the thing is not invincible, and the hunter uses both guile and brute force to defeat the much stronger creature. There is no right or wrong or good or evil here; there is simply the matter of dealing with an intruder and raw survival. In best EC horror comics fashion, Alden throws one last twist at the reader at the end, one that shows that victory is often defined in the long term. In many respects, this comic is a bit of a lark; it lacks the emotional complexity of stories like "Backyard", "Hollow", "Household", and "Hawai'i 1997". That said, given its origins as a webcomic, the comic was meant to be a simple adventure story told in a highly complex manner, and it is as lush and memorable in terms of its visuals as any horror or adventure comic I've read.

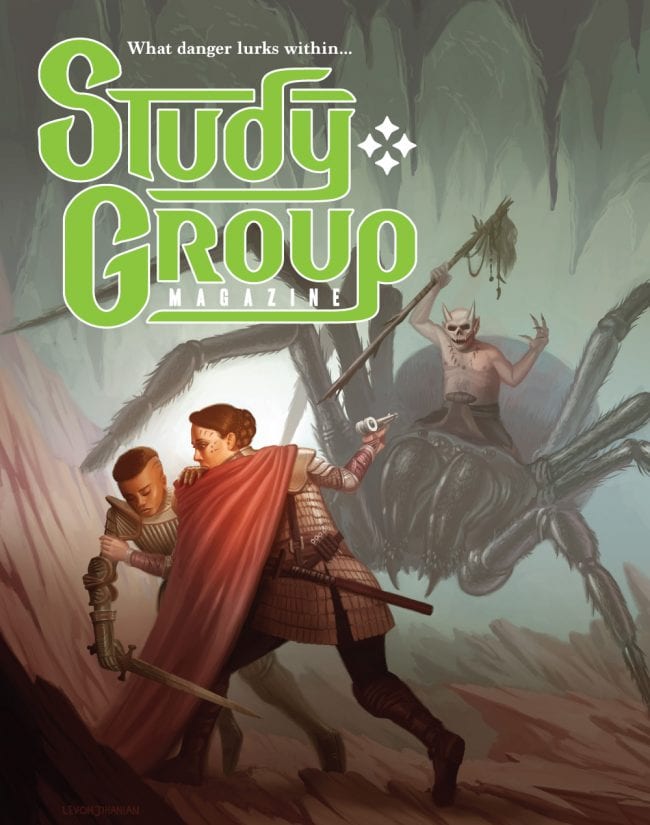

Study Group Magazine #4. In the interest of full disclosure, I have a piece in this issue, which I will obviously not discuss. SGM has always been a representation of the overall aesthetic of Zack Soto and a particular strain of cartoonists; one that believes that comics in all their forms are worthy of at least study and consideration, be they mainstream or alternative. Whereas there used to be a hard line in the '80s between alt-cartoonists and mainstream comics, in part because it was so hard to establish a beachhead for alt-comics, younger cartoonists who have had equal access to both simply seem to care less about such divides. The focus of this issue goes a step further, as it addresses fantasy role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons and the ways in which they relate to comics.

SGM has always had an eclectic mix of commentary and comics. The commentary is especially unusual in this issue, with a conversation between Tucker Stone and features editor Milo George about the old, weird DC miniseries Hawkworld that's thorough, hilarious, and entirely suitable to the material at hand. There's a fantastic piece by Dylan Horrocks (including his own illustrations) about D&D as a world-building device and how that resonates with writing. The world-building is significant because it offers a place to inhabit that is not our world, if only for a little while, and that has a strong impact on one's day-to-day mental health in a positive way. The "craft interview" between George and Farel Dalrymple (told in first person by Dalrymple) is easily the most interesting, revealing piece I've ever read about the artist, going into an incredible amount of detail regarding his influences and techniques. It was especially useful to read given that it talked a lot about The Wrenchies, which is by far his most complex and layered comic.

David Brothers and Joe McCulloch both discuss manga, with Brothers zeroing in on issues related to power in Akira and McCulloch contributing one of his memorable personal pieces about reading his first-ever manga, Golgo 13. It's funny, perceptive, and goes off on tangents that wind up circling back to the original themes. James Romberger's piece on the influences of Jack Kirby is spot-on, with tons of illustrations to back up his points, while Francois Vigneault's interview with fantasy cartoonist Andreas Kalfas links into the way others in the magazine talked about role-playing.

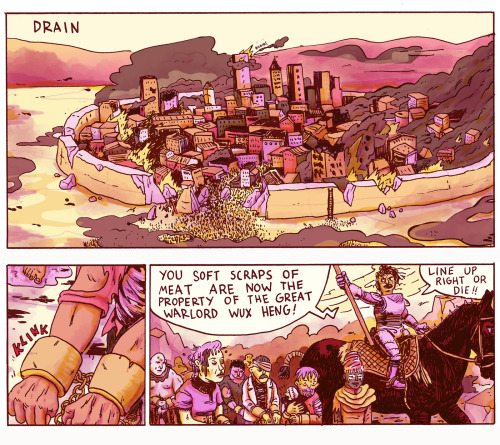

The comics in this issue are also a reflection of Soto, George, and art director Francois Vigneault's tastes, from the oddball Ed Whelan reprint "Comics" McCormick to "Shitbag", an astounding sketchbook story by Lark Pien that is completely unlike her normal style and subject matter. It's brutal, visceral, and even sickening, with the titular creature a force of nature. The story revolves around the cruel machinations of an incestuous brother and sister who torture and kill slaves for fun, and it is done with a fine line and watercolors. There's also a goofy story by Noah Van Sciver, a choose-your-own-adventure-style game by Ian Chachere, and an amusingly violent silent story by Levon Jihanian that fits right into that role player/inventory slot. There's also a long strip by Patrick Crotty that I found to be visually impenetrable. That's unfortunate, given how well the rest of the magazine flowed.