A virtuoso draftsman with an imagination to match, Belgium's Hergé (Georges Remi, 1907 - 1983) is Euro-cartooning's nonpareil. Having sold over two hundred million books in a hundred languages, his creation Tintin is known around the world. Hergé's fame, however, exceeds even the world of comics. When they reach the auction block, his originals now fetch fantastic sums. In 2014, going for €2.65 million, a double-page Hergé spread broke the existing record; last November, a single page went for €1.55 million.

Scrutinized by an army of "Tintinologists", Hergé's work also enjoys an impressive bibliography. Expanded yearly, this can range from PhDs to tomes such as last year's Dictionnaire Amoureux de Tintin. This volume, not atypical, clocks in at 785 pages and features everything from how the artist saw roller skates to his "most overlooked" inheritors.

So how does Paris' Grand Palais picture the subject of Hergé? Amidst so many competing theories, where does the blockbuster stand? Strictly speaking, it's a hagiography traced in la ligne claire. Yet by assembling so many riches, they unwittingly let the work speak for itself – and it proves a disquieting tattle-tale.

Although it is worshipped as a “ninth art” in France, the Grand Palais has never before dealt with the bande dessinée. Here their explicit intention is to elevate Hergé and place him alongside Vélasquez, Warhol and Picasso. Critics have made a lot of this but the show was tailored to justify it. Every day, as soon as it opens, the place is packed with crowds aged "from 7 to 77" – Tintin magazine's summary of its target audience. Yet the show isn't describing merely a master storyteller or a titan of the bande dessinée.

Its portrait is that of a royal figure, an authorised and reified Hergé. A true peer of the very artists he collected, he is seen as a great whose drawing merits comparisons to Dürer and Da Vinci. For brilliance, scope and artistry, the art on show is indeed singular and it can certainly withstand a little overzealousness. In 450 original pieces from all stages of Hergé's life, a visitor gets both the creation myth and apotheosis of his ligne claire. As a bonus, he or she also sees private paintings plus an illuminating survey of Hergé's graphic design.

But all this is deployed in a curious anti-chronology. The expo introduces Hergé via a wall of his paintings, all of which were done during a year in the 1960s. Under the tutelage of abstractionist Louis Van Lint, the artist poured his energies into this different discipline. But the results, while honourable, have little to recommend them. As an abortive outing and a probable source of frustration (if not deep disappointment), they are an odd lead-in.

The paintings introduce a one-room mini-museum stocked with some of the modern art Hergé collected. The contents include six prints by Roy Lichtenstein (an Hergé fan), Jean DuBuffet’s La Cafetière, a Great American Nude from Tom Wesselman and the portrait of himself Hergé commissioned from Warhol. Bolstered by other pieces, including a portrait bust by Tchang Tchong-Jen, the dim room exudes a dusty and dated ambiance. Its real energy comes from the artist's own work: Hergé's riveting sketches for the unfinished Tintin and Alph-Art.

The paintings introduce a one-room mini-museum stocked with some of the modern art Hergé collected. The contents include six prints by Roy Lichtenstein (an Hergé fan), Jean DuBuffet’s La Cafetière, a Great American Nude from Tom Wesselman and the portrait of himself Hergé commissioned from Warhol. Bolstered by other pieces, including a portrait bust by Tchang Tchong-Jen, the dim room exudes a dusty and dated ambiance. Its real energy comes from the artist's own work: Hergé's riveting sketches for the unfinished Tintin and Alph-Art.

The expo has ten rooms in all, each with a theme like "The Curious Fox" (Hergé's Boy Scout name) or "Lesson From the Far East" (the story of the artist's friendship with Tchong-Jen, how it informed The Blue Lotus and transformed his life). At numerous points in many places, Hergé himself pops up on film. He is always modest, jokey and self-effacing; never does he answer a question with any depth. Whether Hergé is asked about the cinema, his work or his art, he remains anodyne. Yet his diffidence masked a sharp and probing mind. The artist was fascinated, for instance, with Balzac’s Human Comedy – as well as inspired by its recurring characters. He loved reading Simenon and Dickens but also Stendhal and Proust. In 1971, he famously exclaimed to the interviewer Numa Sadoul, "Tintin (like all the others) is me, in exactly the way Flaubert said 'I am Madame Bovary!'… ".

Yet with regard to the public, as in the lines of his work, Hergé made himself a master of control. Just like his private feelings, the sharpness of his thinking was kept carefully under wraps. The same way he refined his line over and over, so it conveyed only what he wanted, the artist refined and guarded that face he showed the world. This is a tension palpable throughout the show, one that powered his art and helped to forge his style.

What work, however – and what a style! In so many ways, Hergé's sketches, scribblings and storyboards are magical. At the height of his powers, they simply radiate invention. Hergé kept his energies harnessed via an extreme, labour-intensive process. Once he had decided the basis of a sequence, said the artist, "I use absolutely all the energy in my possession. I draw wildly, furiously, I erase, I scratch things out, I’m full of rage, I swear…I try to give each character's expression and their movement as much intensity as I can ".

Out of "all these lines that blend, cross, run over and under each other" he refined and re-refined until he chose "the one that looks at the same time the smoothest and the most expressive." Above the samples, as a wall text, hangs another quote: You can’t know the extent to which all this is long and difficult, it’s truly a manual labour!...It's as painstaking as a watchmaker’s job. A watchmaker or a Benedictine monk. Or a Benedictine watchmaker.

The resulting line is astonishing in its fluid ebullience and its roots are inspiring. For Hergé was an autodidact with no formal training at all. As a youth who loved images, he explored, imitated and then discarded voraciously. Early on, the artist soaked up everything that attracted him – from children's illustrators like Benjamin Rabier, Christophe and Oncle Hansi (Georges Colomb and Jean Jacques Waltz) right up to Picasso.

Employed towards the end of his teens by the Catholic paper Le Vingtième Siècle (The Twentieth Century), Hergé also fell in love with task after task: photo-engraving, lettering, photo-montage and page composition. The list of contemporaries whose styles intrigued him was just as varied. Some of them were poster artists, like Léo Marfurt, Cassandre (Adolphe Jean Marie Mouron) and Jean Carlu. But René Vincent – who had the same Art Deco smoothness – worked in the world of fashion.

Remi already signed himself “Hergé”. From 17, he used this, the French pronunciation of his reversed initials (G.R.). But the man who helped him consolidate the identity was an outspoken, right-wing Catholic priest.

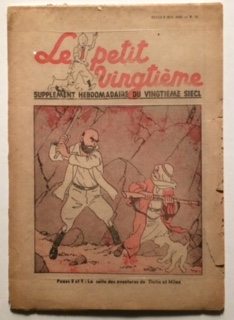

The Abbott Norbert Wallez stood 6'2" tall and weighed 242 pounds. An imposing figure, he was the head of Le Vingtième Siècle’s publisher. Energetic, opinionated and a fervent fan of Benito Mussolini, the enterprising clergymen had actually managed to meet Il Duce. (He was the proud possessor of an autographed portrait). Hergé, who was a quarter-of-a-century younger, found himself impressed by the worldliness of the voluble priest. Asked by the Church to reinvigorate Le Vingtième, Abbott Wallez was bursting with schemes. One of these was a youth supplement, Le Petit Vingtième. In 1928, he asked his young employee to edit it.

No sooner was the magazine established than Wallez had yet another idea. Remi had drawn a boy and his dog for the Catholic Le Sifflet (The Whistle). Could he not turn them into a series for Le Petit Vingtième? The priest even supplied an idea for their début – a trip to Soviet Russia that would show the horrors of communism.

Soon, he had a keen Remi working twelve-hours a day. In addition to the new Tintin strip, Hergé had responsibility for his supplement's covers, layout, typography and illustrations. Yet even on the days he needed to skip lunch, the artist made sure he popped in to see the priest. Wallez, he later said, made everything about their daily discussions interesting. “He was the first person who showed me what intellectual life could be”. In 1932, Hergé married his secretary.

Right up until his death the priest would remain a father figure. Wallez served time in prison for collaboration but, to Hergé, he was always a trusted counsellor. Hergé remained grateful for his first vote of confidence. But, says the artist's biographer Pierre Assouline, he also saw in Wallez, "a spiritual father. Not spiritual in religious terms, but in the deepest sense."

During the 1930s, as well as postcards and stationary, Hergé frequently designed advertising. From 1931, he signed all such efforts "Hergé Studios". Then, in August 1933, after a contretemps with the city's Public Works, Wallez was forced to resign his position. Without his mentor, Hergé became doubtful about Tintin's future. Instead, he looked to advertising and took action to make Hergé Studios legal. Works from its brief existence – which officially lasted less a year – are lavishly displayed.

But Hergé’s promos for toys and travel prove revealing. Their lines are controlled and clean, their compositions neat and minimal. But, stripped of their period context, they lack genuine punch and brio. Rather like Hergé's paintings, they are casualties of a missing ingredient: narrative.

One key to this may lie in Hergé’s childhood, wherein art played a slightly unusual role. Dutiful at school yet difficult at home, he was a rambunctious child who often needed "calming down". His parents learned to accomplish this by giving him tools to draw. (If somehow that failed to work, their next choice was a spanking). In the end, the family communicated largely through drawing.

As an adult, Hergé would say he looked back on childhood "with sadness, morosity and, sometimes, even disgust". The Remi home lacked colour; it had no music, few books and little overt affection. There was also a secret buried at the family's heart: Remi's father and his uncle – twins – were illegitimate. Neither had any real idea about their paternity. Young Georges learned about this mystery only as an adult. As a child, he was simply warned never to ask about or speak of his grandfather.

Remi’s mother was always fragile. Suffering blackouts and depressions, she was frequently hospitalised. Since his business called for travel, Remi Senior charged the young Georges with watching over her. Years later, when she had died in psychiatric care, Hergé was surprised to feel he had never known her. He was 39 at the time and her death triggered the first of several breakdowns.

All Belgian artists of Hergé's generation endured not one but a pair of world wars. They had been born into an ultraconservative, mainly Catholic country – a colonial power that enjoyed a certain prestige. But in 1914, when Hergé was seven, that world was commandeered by the German Army. Their presence lasted four years, a cold, frightening, hungry period. Even when the occupation ended, shortages continued.

If none of this offered a recipe for happiness, neither did it make Hergé into a rebel. As visitors discover in the expo's many photos, he always had the appearance of a model character. Every snap shows him as rigid, reserved and smartly dressed. But even a glance at his working pages will disclose another story. Hergé's drawings are dark with battling versions of even the smallest gesture. Their action spills over boundaries, their faces melt from one emotion into its opposite and the frames are filled as much with hesitations as with decisions.

The art reveals what the exhibition doesn't state: this was a Boy Scout who slept around on his (first) wife, a writer of adventures with no time to spare for travel, a self-promoter who – even under the Nazis – kept his eye on the main chance. All this and more is present in the work, which suggests the price Hergé paid for all that discipline.

There have been many theories about Tintin's "adolescence": an existential form of youth untroubled by sex or family. In the view of Hergé biographer Benoît Peeters, the artist added "very adult qualities to his own vision of childhood". For the psychologist Serge Tisseron, author of Tintin chez le psychanalyste (loosely, "Tintin on the couch"), "His books are the history of a child who tells you how he sees all the adults around him and who reconstructs how they speak… Even his vistas are seen from the height of a child."

The artist himself defined Tintin's status more cryptically. He liked to paraphrase Jules Renard and saying, "Not everybody can have the luck to be an orphan!".

Two things brightened Hergé's own childhood: the cinema and the Boy Scouts. Taken from his earliest years to see silent films, he loved losing himself in their mute, alternate world. As an artist, he cited the significance of Charlie Chaplin, Harry Langdon and Buster Keaton. But Hergé was also influenced by early Westerns and by the likes of criminal mastermind Fantomas. The silent screen helped Hergé learn how to advance a narrative and he always remembered its protocols and etiquette.

If his family were fallible, the boy scouts brought him "camaraderie, nature and adventure". For Hergé, scouting always remained "the great memory of my childhood." It gave the artist precepts he felt he should always value, especially those which had to do with friendship and loyalty. After the Occupation, they were his rationale for supporting collaborationist friends.

Was Hergé – as so many critics insist – a Fascist and a racist? Was he anti-Semitic? At Hergé, all such questions go unaddressed. Fourth in the show's ten rooms is one entitled "Success and Torment" which concerns the artist’s wartime work at a pro-Nazi paper. For Hergé's career, this choice was critical. During the Occupation, with its controls, restrictions and paper shortages, it kept him visible and enabled his books to appear. Plus (as the artist joked to a friend) right after he joined, the paper's circulation doubled.

But with the Liberation, things changed radically. Arrested four times and subsequently investigated, Hergé was ruled an "incivique" – a proscribed non-citizen. He was barred from ever again practicing his profession.

It was the lowest point of the artist's life. Yet, unexpectedly, Tintin came to his rescue. The character, as Pierre Assouline has observed, saved Hergé twice. In the first instance, Tintin kept him out of prison. Many of the artist's friends and colleagues received serious sentences, others had to flee and a few – like the editor Paul Herten – were put to death. Yet, says Assouline, "You simply couldn't put Tintin in prison. Anyone who did that would have been covered in ridicule."

But Hergé's humiliation was total and public. One resistant weekly, La Patrie or The Homeland, even ran a parody of his strip called "The Adventures of Tintin in the Land of the Nazis". This pictured his characters rejoicing at their freedom, with Tintin's faithful dog boasting that Hergé never made him into a German shepherd.

But Hergé's humiliation was total and public. One resistant weekly, La Patrie or The Homeland, even ran a parody of his strip called "The Adventures of Tintin in the Land of the Nazis". This pictured his characters rejoicing at their freedom, with Tintin's faithful dog boasting that Hergé never made him into a German shepherd.

Privately, the artist said death would have been preferable.

The second time, what saved him was Tintin's market value. One of the character's lifelong fans was a former resistant named Raymond Leblanc. With a spotless war record, Leblanc found success launching movie and romance magazines. He wanted to enter the youth market, for which he had conceived a weekly called 'Tintin'. Leblanc searched out Remi and outlined his project. The artist, at an all-time low, was extremely doubtful. But a determined Leblanc soon succeeded in clearing his name. When they launched the magazine in 1946, a grateful Hergé even let him license Tintin products.

The rest of the Tintin saga is history – but its author never recovered. Hergé underwent years of recurrent depression and breakdowns. There was also a certain freedom, a singular spontaneity, that his art could never recapture.

The essence and heart of Hergé's oeuvre, his most extraordinary achievements, were put in place during the '30s and '40s. In the exhibition’s rooms, "A Family on Paper" and "A Myth is Born", the great treasures are his works from those decades. As the great bédéiste Jacques Tardi maintained, "Nothing has ever been drawn more beautifully than the first black-and-white Tintin books. The soft sensuality of the lines continues to move me."

The essence and heart of Hergé's oeuvre, his most extraordinary achievements, were put in place during the '30s and '40s. In the exhibition’s rooms, "A Family on Paper" and "A Myth is Born", the great treasures are his works from those decades. As the great bédéiste Jacques Tardi maintained, "Nothing has ever been drawn more beautifully than the first black-and-white Tintin books. The soft sensuality of the lines continues to move me."

Hergé's best trait is indeed peerless. As his colleague Edgar P. Jacobs observed to Benoît Peeters, " What always struck me about Hergé's drawing was the extraordinary vibrancy of his line… a good part of his genius resided in those lines that never stopped moving, whether he was drawing a plan, a piece of furniture or the fold of a garment."

Yet the universe they delineate is, in many ways, not one for children. Recently Benoît Peeters, speaking on French radio, drew attention to the work's darker side. "Hergé's world is also a universe filled with terror… the alcoholism of Captain Haddock, the kind of dreams Tintin can have, the Yeti, the mummy, the suicides, the opium den…" Children can sense, he added, that Hergé never takes them for babies. "As a child, I was terrified by Tintin! I would often skip over pages to avoid a shock."

Underneath that beautiful line and its pursuit of clarity, the fears one cannot help but sense were Hergé's deepest. His drawings are explosive; they absolutely erupt with conflict. It's an intensity best summed up by Remi's friend Marcel Stahl, who knew him from the 1930s up until the end of his life. "Georges had a kind of anxiety… He didn't have the knack for happiness. He never knew how to experience life like a normal person. There was always some problem, a well of dissatisfaction that affected everything in his life. And fame changed none of this."

The Grand Palais blockbuster finishes up with a giant room, a "salon of the selfie". It's a space created especially for guests, a backdrop against which they can immortalize the visit. The room is covered by an enormous mural which, in 1973, appeared on the New Year's card of Studios Hergé. Here are the boy reporter and Milou, Haddock, Thompson and Thomson, Castafiore and Calculus, with all the villains they fought and many of their compatriots. Some hold placards or banners emblazoned with positive sentiments. "Peace", they read, and "Merry Christmas", "Control Violence", "Protect the Environment". It's a fixed pantheon, with all the reference points of an exemplary childhood.

Yet Tintin, just like Hergé, was never wholly exemplary and never really a child. Perhaps that's why, despite the crowds, the room remains empty.

• Hergé runs through 15 January at the Grand Palais in Paris; for Tintin fans, the catalogue is a treat