We asked our contributors to send us their Best of 2016 lists. Many obliged! Thanks to all for doing this. Now onto 2017. -Eds.

Walter Biggins

1) Hugo Pratt, Corto Maltese: The Ethiopian (IDW)

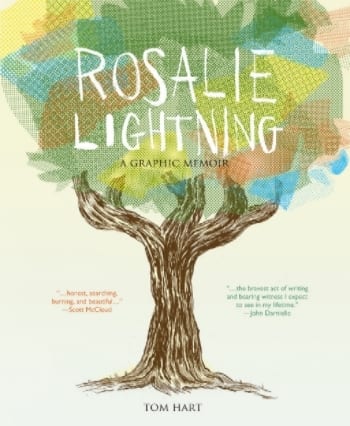

2) Tom Hart, Rosalie Lightning (St. Martin's)

3) Ben Katchor, Cheap Novelties: The Pleasures of Urban Decay (D&Q)

4) Michel Rabagliati, Paul Up North (BDang)

5) Moebius Library: The World of Edena (Dark Horse)

Honorable mentions:

John Porcellino, King-Cat #76 (John Porcellino)

Gilbert Hernandez, Garden of Flesh (Fantagraphics)

Lewis Trondheim and Keramidas, Mickey's Craziest Adventures (IDW)

Julie Doucet, Carpet Sweeper Tales (D&Q)

Notes: 3 of my 5 are reissues. Apparently, no women or no nonwhites made my cut until the honorable mentions. I suck. I'll do better next year.

Robert Boyd

2016 Favorites

My favorites from 2016. There are still a few on my “to read” pile that might make it—for example, The Greatest of Marlys would almost certainly have made it if I had read it in time.

They are in order from smallest to largest.

Endless Monsoon IV: Very Pleasant Transit Center by Sarah Welch. 56 pages, two-color risograph, 5” x 7”. This is a very slow-moving series about two young women trying to make their way in a world of somewhat straitened circumstances. The art is transmits the humid, sweaty feel of Houston very well.

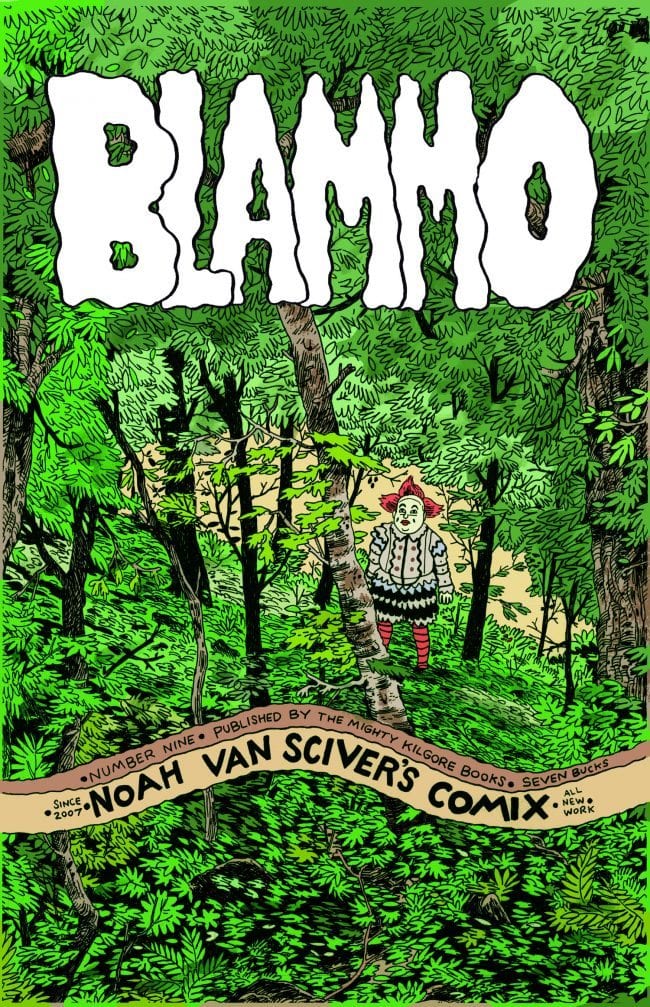

Blammo number nine by Noah Van Sciver (Kilgore Books ). 44 pages, black and white comic book. The two long stories in here are classic '90s-style alternative comics stories—one is autobiographical (Van Sciver inadvertently offends a sensitive soul at the Center for Cartoon Studies and flashes back to his Mormon childhood) and the other a short story about a museum guard who starts to paint paintings in the style of long dead abstract painter being shown at the museum. Both stories are really good, and I liked especially have despite working in the museum, the museum guard is clearly doesn’t know the social etiquette of being in the art world. Van Sciver shows how difficult it is to cross the class divide because one must know the rules of the other side—it’s like a mini-lesson in Pierre Bourdieu.

What is Obscenity? The Story of a good for nothing artist and her pussy by Rokudenshiko (Koyama Press) 178 pages, 6” x 8.5” squarebound book combining color and black and white pages. This book combines articles and comics to tell the first-person story of a Japanese artist who spent time in jail for producing obscene art—specifically for providing digital file of her pussy for 3-D printing in a crowdfunding campaign. The comics here are straightforward and highly amusing, and her story is utterly incredible.

American Blood (Fantagraphics Books) 208 pages, 5.9” x 8.6” squarebound paperback book printed with purple ink. This book collects various self-contained stories that Marra self-published in his Traditional Comics line between 2009 and 2013, including The Incredibly Fantastic Adventures of Maureen Dowd. I had never read these comics before but they were an eye-opener. Funny, satirical, etc.—if someone could take the best drawings that male high-school stoners from 1976 until now drew on their desks and make comics out of them, they would approach this book in sheer awesomeness.

Scorched Earth by Tom Van Deusen (Kilgore Books ) 82 pages squarebound, 6” x 9”, black and white). There is a long tradition in narrative art of having utterly reprehensible cads as protagonists: Sebastian Dangerfield in The Gingerman, Harry Flashman in the Flashman books, Withnail in Withnail and I. And now in Scorched Earth, Tom Van Deusen can be added to that immortal parade of assholes. His genius twist on the time-honored genre is to make himself the hateful but hilarious protagonist.

Megg & Mogg in Amsterdam by Simon Hanselmann (Fantagraphics Books) 160 pages, full-color, hardcover. There seems to be a theme with my choices this year—books about self-absorbed partiers. The trip to Amsterdam happens only at the very end, and it’s not any different from their current existence—just colder and wetter. Werewolf Jones descends to new levels of depravity, including making money of his 10-year-old quasi-feral son’s cam shows. But the real annoyance is Owl, the only one who seems to have a job. I find this book repeatedly hilarious.

Demon volume 1 by Jason Shiga (First Second) 176 pages, black-and-white, paperback. The incredibly bloody story of Jimmy Yee, a man who commits suicide over and over. At first it reads like an epic case of gaslighting, but the actual explanation is weirder than I expected. A bizarre concept taken to a logical extreme in a very amusing, violent way.

Founding Fathers Funnies by Peter Bagge (Dark Horse Books) 86 pages, color and black and white, hardcover, 6.5 x 9 inches. I’ve loved Peter Bagge since Neat Stuff (see below) and loved these strips when they first appeared as back-up features in various Bagge comic books. They work best as short stand-alone stories, but I’m very glad to be able to read them collected into a book.

Blubber #2 by Gilbert Hernandez (Fantagraphic Books) 25 pages, 6.5 x 9 inches, black and white. Blubber is Gilbert Hernandez’s one-man anthology of superheroes and monsters fucking. When I read it, I wonder—why hasn’t this been the dominant genre in comics for years? It is my favorite comic book of 2016. I haven’t read issue 3 yet, so I have that to look forward to.

Nod Away by Joshua W. Cotter (Fantagraphics Books ) 240 pages, 7.8 x 10.2 inches, black and white. This ambitious science fiction story (it’s meant to be the first volume of seven) is packed full of ideas and characters and great artwork. Unfortunately it ends on a cliffhanger. Now I kind of wish I had waited until all seven volumes were out before I read it!

The Eltingville Club by Evan Dorkin (Dark Horse Comics ) 144 pages, black and white and color, 8 x 11 inches. These stories have appeared in various anthology comics, including Dorkin’s one-man anthology Dork, since 1994. The Eltingville Club started at the high tide of Wizard magazine, which at the time seemed like the ne plus ultra of degenerate fandom. Dorkin captured that vibe in his dense, hilarious comics. But fandom, if anything, managed to reach new lows, particularly regarding women fans—see “fake geek girls,” Gamergate, and incessant online and IRL harassment—and in bringing his Eltingville Club members to the present, Dorkin drags them even lower than where they started. It’s cruelly fun to read.

Peplum by Blutch (New York Review Comics ) 160 pages, 8.7” x 11.4”, black and white. A picaresque adventure story set on the frontiers of the Roman world, it makes me imagine what David Malouf’s An Imaginary Life would have been like if drawn by Frank Robbins or Alberto Breccia. Peplum is the mysterious story of a young imposter pretending to be a Roman nobleman Publius Cimber is part of an expedition that has recovered a woman frozen in ice. The ice miraculously does not melt despite its long, eventful journey. “Cimber” loves her, which is the source of all his misadventures. Blutch’s chiaroscuro style is breathtaking

Sir Alfred No. 3 by Tim Hensley (Pigeon Press) 40 pages, 9.75 a 13 inches, color. The Adventures of Bob Hope comic book lasted 18 years, and Tim Hensley has aped its format to tell a series of anecdotes about Alfred Hitchcock. A lot of them are familiar stories if you know your Hitchiana, but Hensley rarely just gives you a straight-ahead retellings of them. His humor is oblique; it’s not about a series of gags. That, combined with his pastiche of Harvey Comics drawing style, make this one of 2016’s best.

Neat Stuff by Peter Bagge (Fantagraphics Books). 488 pages, 9” x 11.6 inches, two volumes, hardcover. This one doesn’t completely count since I read every single issue of Neat Stuff when they came out. Bagge describes his readership as falling in the “lone weirdo” demographic. It has his immortal characters, Girly Girl, Goon on the Moon, Studs Kirby, Chet and Bunny Leeway, Junior and the Bradleys. But it also has a bunch little masterpieces that people may have forgotten, like “Do You Know Where It’s At?!?” and like “The Fall and Rise of Zoove Groover.”

The Nib , edited by Mat Bors, featuring a large variety of cartoonists including Tom Tomorrow, Matt Lubchansky, Emily Flake, Rich Stevens, Jen Sorensen, Keith Knight, etc. These are all clever, funny political cartoonists, but what makes the Nib great are its journalistic comics such as Jess Ruliffson’s stories of life in the military, Kate Moon’s story on the Great Barrier Reef, and Ben Passmore’s first person “Letter From a Stone Mountain Jail”. Day after day, the Nib provides amazingly good political and journalistic comics. It’s a brilliantly edited site.

Pat Palermo's Galveston Drawing Diary by Pat Palermo. Daily comics blog. Pat Palermo is a Brooklyn artist who is currently doing a residency at the Galveston Artists Residency in Galveston, TX. Since he arrived in August, he has been drawing a page of comics every day in pencil on lined yellow paper, scanning them, and posting them on his blog. They started off being about a fish out of water—a Brooklyn guy on a sub-tropical Texas island—and that is still a theme he returns to frequently. But his coverage of the presidential campaign and its aftermath slowly grew in importance as time went on. His drawing is fantastic but also has an appealingly casual quality.

Jessica Campbell

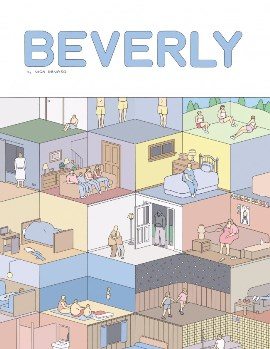

Beverly by Nick Drnaso

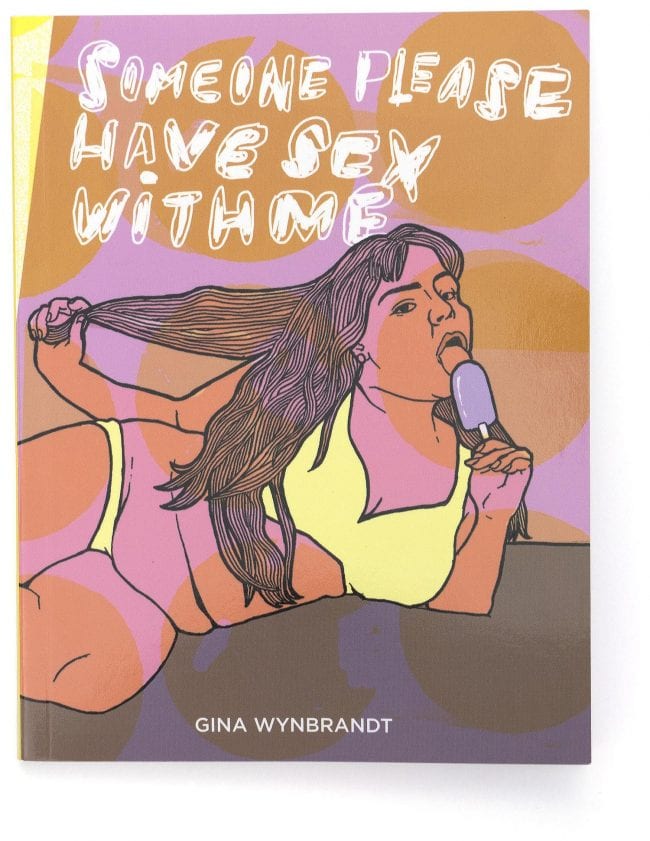

Someone Please Have Sex With Me by Gina Wynbrandt

Pioneering Cartoonists of Color by Tim Jackson

Libby's Dad by Eleanor Davis

Epoxy Cartoon Magazine by John Pham

RJ Casey

What Am I Doing Here? by Abner Dean

Unwell by Tara Booth

Blammo #9 by Noah Van Sciver

She's Done It All! by Beatrix Urkowitz

One-pagers by Gizem Vural

Rob Clough

1. Rosalie Lightning, by Tom Hart

2. Blammo #9, by Noah Van Sciver

3. Someone Please Have Sex with Me, by Gina Wynbrandt

4. The Unofficial Cuckoo's Nest Study Companion, by Luke Healy

5. Exits, by Daryl Seitchik

Anya Davidson

This is random smattering of books and zines I liked in no particular order. Can I say that I think these kinds of lists are arbitrary, because there is a dizzying number of brilliant books out there that I haven't read, so this is more of a "list of things I read that I greatly enjoyed" than a best of?

a) Dias de Consuelo by Dave Ortega #'s 2 and 3

Beautifully executed serialized biographical comic about Dave's grandmother.

b)Perfect Hair by Tommi PG

Dark and funny painted short stories about sex and loss

c) Crim Coblend's Garage Island #3 by Max Huffman

Snappy strips drawn inventively. Shades of Daniel Torres and Lale Westvind

d) Almost Completely Baxter by Glen Baxter

This is a reprint by New York Review Comics. Absurd and transcendent gags.

e) Beverly by Nick Drnaso

Nick has an uncanny ear for dialogue and is finely attuned to the beauty and pain of the mundane.

Andrew Farago

Rosalie Lightning, Tom Hart

March, Book Three, John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, Nate Powell

Demon, Jason Shiga

Power Man & Iron Fist, David Walker & Sanford Greene

Hot Dog Taste Test, Lisa Hanawalt

R. Fiore

New Comics:

- King Baby (Kate Beaton)

- Patience (Daniel Clowes)

- Sir Alfred (Tim Hensley)

- Peplum (Blutch)

- The Twilight Children (Gilbert Hernandez and Darwyn Cooke)

- The Boys of Sheriff Street (Jerome Charyn and Jacques de Loustal)

- Nicolas (Pascal Girard)

- The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (Sonny Liew)

Old Comics:

- What Am I Doing Here? (Abner Dean)

- Trump: The Complete Collection (Harvey Kurtzman et al.)

- Mandrake the Magician: The Sundays Volume 1 (Lee Falk and Phil Davis)

- Tim Tyler’s Luck (Lyman Young and Alex Raymond)

- Moebius Library: The World of Eden

- Complete Crepax Volume 1: Dracula, Frankenstein and Other Horror (Guido Crepax

- Robert Crumb Sketchbook 1964 to 1968 *. Raymond Pettibon: Homo Americanus

In gathering my personal nominations I came across a couple of Amazon orders of forthcoming and just released books I’d made in April that illustrate the sheer profusion of notable comics that came out in 2016. One was for The Adventures of Dieter Lumpen (Jorge Zentner), Providence (Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows), The World of Edena (Moebius), and Alack Sinner: Age of Innocence (Munoz and Sampayo, still forthcoming); the other was for Red Barry Volume 1 (Will Gould), Mandrake the Magician Dailies Volume 1, Corto Maltese: The Ethiopian (Hugo Pratt), Tim Tyler’s Luck, and Dirty Duck (Bobby London, still forthcoming); not to mention another order I made a couple of weeks later including numbers 1, 5 and 6 on my new comics list and number 1 on my old comics list.

The ask was for a Top Five, but I stretched it out to encompass what I consider the First Division; books that stood above the rest, that had some quality of revelation to them. My ground rules were that anything that had its first publication in English in the United States in 2016 was a new book. Numbering is in order of preference, but in the old comics category the order of finish is arbitrary after the top two. The Pettibon is not ranked because quite frankly though I have this brick on the shelf I haven’t tackled it yet, but I can’t imagine this comprehensive retrospective of the Posada of the Los Angeles telephone pole couldn’t be one of the major books of the year.

Getting down to individual cases . . .

Hundreds of discrete choices each made for its own reasons coalesce one on top of another until they form a way of life, one that none would have imagined if they had set out to design a way of life, and yet compliance is nearly universal. One unit of the crowd sidesteps into an alleyway and says, What Am I Doing Here? In his collection of psychic vignettes Abner Dean blazed not a trail but a road not taken. He turned the cartoon caption from a joke into a poetic provocation that interrogates the image. Drawing his characters naked serves to impose awareness that they are creatures from a natural world, inhabiting their own artificial creation. With no intention to that I can discern he also portrays a segregated society, which only admits one kind of person. Dean doesn’t imply that this is a society on the brink of a social revolution, and yet 30-odd years a pop band would be rephrasing the question: “My God, what have I done?”

I lead with my top vintage pick because my top contemporary pick, Kate Beaton’s King Baby, is very much in the Abner Dean tradition. As it deals with happy things Beaton’s book lacks Dean’s sense of quiet desperation, but it has the same quality of seeing commonplace things with eyes both unsparing and enchanted. Where Beaton’s first venture into children’s picture books The Princess and the Pony seemed to strain a bit to bend its tale to its moral, King Baby is a perfectly executed little gem of observation, capturing something fundamental about the strangeness of infancy in an affluent society, from its say-it-all title to its elegant punchline. I think it can be assumed that any expectant mother with a comics-conscious friend can expect to be receiving this book as a baby shower gift for the foreseeable future. They’ll read it themselves and then read it to their children when time comes.

Running quickly through the rest, Patience turns the wish-fulfillment tale on its head with a passion that disintegrates irony, Sir Alfred is another example of perfect execution of a concept on multiple levels, Peplum is as slashing in its narrative as it is in its artwork, The Twilight Children left you wishing that its creators had just had more time, The Boys of Sheriff Street was a prime slice of Charyn American mythopoetics, Nicolas showed the enduring appeal of the Blechman fleck better than Blechman himself, and Charlie Chan Hock Chye was just a shock in its Maus-like encapsulation of an era.

When the modern era of classic comics reprints began you wondered when the bubble would burst. Was there really a readership for all these fifty dollar books, you’d wonder. Now we are coming to the point where we’re running out of classic comic strips. The Complete Peanuts is complete. Mickey Mouse has donned the Bing Crosby hat, which means the good times are just about over. In Dick Tracy we see the first glimpse of Moon Maid over the horizon, which means it’s about to go out in a blaze of lunacy. Little Orphan Annie is still more or less in the middle of its run, but you feel like you’ve seen about every move Harold Gray has, several times. The number of comic strips with wide name recognition and a ready contemporary readership is quite limited, and it remains to be seen whether a readership can be found deeper dig into the likes of Abbie an’ Slats or Barney Baxter. At the same time the addition of Dover Graphic Novels and New York Review to the ranks of retrospective publishers seems to have been a tipping point, and we’ve never had a wider range of comics of the past at our ready disposal. This does not even take into account the print-on-demand samizdat that is bringing us the high-quality likes of Kim Weston’s The Unavailable Carl Barks.

The icing on the cake of 2016 was the long-promised Trump: The Complete Collection (though a more honest title might have been Trump: Both Issues). It’s an exquisitely produced look at a road not taken, Harvey Kurtzman’s dream of a humor magazine with the full production values of a slick magazine that would be fulfilled fourteen years later by the National Lampoon. It is perhaps more notable for what it promised than what it delivered, but what it promised was tantalizing. I ordered Mandrake the Magician: The Sundays in a spirit of speculation, half expecting a mediocrity on the level of Lee Falk’s other strip The Phantom. Fortunately Phil Davis turns out to be a sort of Alex Raymond Light, and the absurd premise of a stage magician operating in the real world as a genuine wizard, evening clothes and all, in practice turns it into a kind of comic strip Weird Tales.

Do you suppose I might get by with endorsing Mandrake without dealing with Lothar issue? Didn’t think so. Racially demeaning characters might be divided into active and passive. The actively demeaning character acts out racially stereotypical traits, as it might be cowardice, ignorance, hedonism, sloth or superstition in such a way as to imply that they are characteristics of a race. In a passively demeaning character the demeaning characteristics are implicit, and depend on the assumptions of the readership. Mandrake’s enforcer Lothar is of the passive variety. He is capable, courageous, and loyal, yet he is a servant and refers to Mandrake as “Master” for no other apparent reason than that it is the "natural" order of things. Since Americans do not normally require their paid servants to address them as Master, the implication is that it’s Lothar’s idea. Lothar’s speech is pidgin, and yet English is not his native language. His adherence to a comic strip version of native dress could be taken as demeaning, and yet it does have some relation to actual African native dress. Namely, to wear a leopard skin is the particular privilege of a Zulu chief. So, potential dignity points for that, but it raises the question, why is this leader of a fiercely independent people calling this fop Master?

Finishing out my list, in Tim Tyler’s Luck you got to see Alex Raymond become Alex Raymond, The World of Edena is as much a feast for the eye as it is a famine for the mind, Complete Crepax Volume 1 is most notable for giving the first long look at Valentina I’ve been able to get, and Taschen’s Robert Crumb Sketchbook 1964 to 1968 presents these seminal early pages without the reproduction limitations imposed on them the last time around. The coming year has a hard act to follow.

Craig Fischer

In the documentary Cartoon College (2012), Scott McCloud argues that comics is now too vast a world for any single person to understand, metaphorically noting that “parts of comics have dipped beyond the horizon line.” And I’m one person presuming to name The Very Best Comics of 2016. My vision is flawed, I can’t see beyond the horizon, but here’s a handful of books from last year that I found moving, significant, funny, and/or edifying, in alphabetical order:

House of Women #3, Sophie Goldstein (self-published). In bringing her science-fiction rewrite of Black Narcissus to a lusty conclusion this year, Goldstein shows off her growth as an artist beyond The Oven and her other previous comics. When the three issues of House of Women are collected into a single volume by AdHouse, Fantagraphics or Drawn & Quarterly—it’s only a matter of time—will the publisher replicate the attention to design and printing (those lavish die-cut covers and molasses-thick spot blacks) that Goldstein put into her self-presentation of the material? I hope so.

Providence #7-11, Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows (Avatar). Almost a year ago, I wrote a long TCJ article analyzing the first six issues of Providence, and now I’m including the five issues that came out during 2016 on this Best-Of list. It’s remarkable, a deep dive into H.P. Lovecraft that also shows off Moore’s ability to structure a dense literary story in visual form. Providence #11 switches time and space between panels as much as Gilbert Hernandez’s most experimental work and still provides a carefully-planned, satisfying conclusion to the tale of protagonist Robert Black. One final issue awaits us in 2017, and I have no idea what’s going to happen next. I wish I could say that about other comic books.

Rolling Blackouts: Dispatches from Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, Sarah Glidden (Drawn & Quarterly). Very early in Blackout, Glidden asks an independent reporter (also named Sarah) to define journalism, and she replies, “anything that is informative, verifiable, accountable, and independent.” Makes sense, until the rest of the book reveals how messy and complicated the practice of journalism can be, in ways that are bracing, mature correctives to simple-minded Trumpist post-factualism. Further, Glidden’s tight focus on a tiny cadre of reporters allows them to emerge as fully-formed characters, especially a veteran and defender of the Iraq War who confronts people and places forever changed by 21st-century American foreign policy. “Maybe the question really is: what is journalism FOR? What’s the point?”

Rosalie Lightning, Tom Hart (St. Martin’s Press). Obviously, the drama of Lightning circles around the incomprehensibly sad death of Tom Hart and Leela Corman’s three-year-old daughter, but it has so much more to offer than tragedy and despair. As I re-read the book, I found myself warmed by the gymnastics Tom and Leela go through to sell their New York apartment—they function as a close-knit, loving unit before and after their disaster—and the cascade of allusions (to The Vault of Horror, Louis, Astro Boy, My Neighbor Totoro) Hart uses to represent and process his feelings testify to the power of art to give our lives meaning and hope.

Sick, Gabby Schulz (Secret Acres). I have a friend named Toney who’s a horror film connoisseur, who’s brought movies like Audition (1999) and Martyrs (2008) into my life. When I gave him Schulz’s Sick for a Christmas present, he replied, “This book is almost too pessimistic and grim, even for me.” I get that. It’s harrowingly painful to watch Schulz’s physical illness—his unrelenting fever, his bloody shits—spiral into mental illness, into an anhedonia so black that Sick reads like (to paraphrase Cioran) a barely postponed suicide. But boy, can Schulz cartoon. His drawings of a child choked by a ghoul (a metaphor for domestic abuse) and a tableau of “all the beautiful people enjoying this beautiful world” (a Hell worthy of Bosch) are beautiful in their craft and directness of purpose. Toney again: “It is a singular example of an artist’s angry fist-wave at the cosmos…a totally original work.”

Best book about comics: Hellboy’s World: Comics and Monsters on the Margins, Scott Bukatman (University of California Press). Hellboy’s World is an examples of academic comics criticism that is both full of intellectual insight and a blast to read. In lucid, often funny prose, Bukatman describes Hellboy as “a Howard Hawks movie set in an H. P. Lovecraft universe with art direction by Jack Kirby”; traces Mike Mignola’s love of literary occult investigators and characters who deny preordained destinies (like Pinocchio’s refusal to be a puppet); and discusses how Mignola’s bibliophilia influences Hellboy stories and the packaging of those stories into gorgeous library editions. (Bukatman even fruitfully compares Mignola with Yasujiro Ozu.) Hellboy’s World is pretty lavish itself, with full-color illustrations that raise the bar for future scholarly monographs.

Runners-Up:

Bacchus Volume Two, Eddie Campbell (Top Shelf/IDW) / Casanova: Acedia # 5-7, Matt Fraction, Fábio Moon, Michael Chabon and Gabriel Bá (Image) / Comic Book Creator #11-13, edited by Jon B. Cooke (especially #11, devoted to Gil Kane) / Criminal 10th Anniversary Special, Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips (Image) / Critical Chips: 10 Contemporary Comics Essays, edited by Zainab Akhtar (self-published) / Corto Maltese: The Ethiopian, Hugo Pratt (IDW) / Epoxy Cartoon Magazine, John Pham (self-published) / Frontier #11 (“BDSM”), Eleanor Davis (Youth in Decline) / Hellboy in Hell #10, Mike Mignola (Dark Horse) / Laid Waste, Julia Gfrȍrer (Fantagraphics) / Patience, Daniel Clowes (Fantagraphics) / Sir Alfred #3, Tim Hensley (Pigeon Press) / Talk Dirty to Me, Luke Howard (AdHouse) / The Weight #4-5, Melissa Mendes (serialized online/self-published).

Shaenon Garrity

1. March: Book 3 by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell

2. Rosalie Lightning by Tom Hart

3. Demon by Jason Shiga

4. Otherworld Barbara by Moto Hagio

5. Patsy Walker a.k.a. Hellcat! by Kate Leth and Brittney Williams

Richard Gehr

Der Räuber, Tilo Steireif & Robert Walser (Haus am Gern)

Smoke Signal #25

Megg and Mogg in Amsterdam and Other Stories, Simon Hanselmann (Fantagraphics)

Underworld: From Hoboken to Hollywood, Kaz (Fantagraphics)

Patience, Daniel Clowes (Fantagraphics)

R.C. Harvey

Best comics-related (history, biography) books: Tim Jackson’s Pioneering Cartoonists of Color, a much-needed resource; The Life and Art of Wesley Morse, the "lost" artist who produced engagingly rendered 8-pagers and nightclub illustration.

Comics collections: Gag on This: The Scrofulous Cartoons of Charles Rodrigues.

Graphic novel: Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (shows how the form can be expanded and exploited).

Best comic books (in descending order, so you can use the first, which is 5th on my list, and drop the rest; or not): Cage (revitalizing and re-energizing the drawing part of comics), Strange Fruit (no lines in the art; just color—a painted book), Lady Killer (simply outrageous but superbly drawn).

Biggest Disappointment: Tokyo Ghost (brilliantly drawn, but the story is tepid stuff)

Anne Ishii

Bas Jan Ader by Kevin Czap, Ley Lines 8 (Czap Comics)

Fatherson by Richie Pope, Frontier #13 (Youth in Decline)

Yes, Roya by C. Spike Trotman and Emilee Denich (Iron Circus)

Gorgeous by Cathy G. Johnson (Koyama)

Libby's Dad, Eleanor Davis (Retrofit)

Monica Johnson

1. Rosalie Lightning, Tom Hart

2. The Complete Wimmen's Comix

3. Disaster Drawn, Hillary Chute

4. Blackbird, Pierre Maurel

5. Don't Come in Here, Patrick Kyle

John Kelly

We Told You So: Comics As Art, by Tom Spurgeon with Michael Dean

Krazy: George Herrriman, a Life in Black and White by Michael Tisserand

The Complete Neat Stuff by Peter Bagge

More Heroes of the Comics, by Drew Friedman

Underworld: From Hoboken to Hollywood, by Kaz

Robert Kirby

1. Rosalie Lightning by Tom Hart (St. Martin's)

2. Turning Japanese by MariNaomi (2dcloud)

3. Our Mother by Luke Howard (Retrofit)

4. Band for Life by Anya Davidson (Fantagraphics)

5. Wendy's Revenge by Walter Scott (Koyama)

Fave self-published minicomics are (a tie) The Warlok Story by Max Clotfelter & Zebediah Part III by Asher Z. Craw

MariNaomi

Rolling Blackouts by Sarah Glidden

Trying Not to Notice by Will Dinski

Rosalie Lightning by Tom Hart

Virus Tropical by Powerpaola

Handbook by Kevin Budnik

Chris Mautner

Sir Alfred #3 by Tim Hensley

Peplum by Blutch

Laid Waste by Julia Gfrorer

Big Kids by Michael DeForge

Ganges #5 by Kevin Huizenga

Joe McCulloch

10. Hellboy in Hell #10 (Mike Mignola, Dave Stewart, Clem Robins)

9. Puke Force (Brian Chippendale)

8. š! #25 (eds David Schilter, Sanita Muižniece, Berliac)

7. Ding Dong Circus (Sasaki Maki, Ryan Holmberg translation)

6. Ganges #5 (Kevin Huizenga)

5. Laid Waste (Julia Gfrörer)

4. Carpet Sweeper Tales (Julie Doucet)

3. Peplum (Blutch, Edward Gauvin translation)

2. Sir Alfred No. 3 (Tim Hensley)

1. Rosalie Lightning (Tom Hart)

Jason Miles

These are the 2016 comics that hit me hardest, stayed with me, nagged me.

In no particular order:

Blubber by Gilbert Hernandez

What me worry? These have been the most important comics to me.

Patience by Daniel Gillespie Clowes

Painfully good.

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden by Annie Murphy

Annie does that Alan-Moore-thing; illuminating the most curious and the most common injustices... crimes that we're all vaguely aware and actively ignoring. Elemental detective work at its finest.

The Future of Art 25 Years Hence by Gary Panter

Beautiful, beatific absorbant. Humbling.

Love and Rockets vol. IV #1 by Beto + Xaime

Love and Rockets is my favorite thing made by humans. It's more than that. The characters are real. I'm constantly wondering what Hopey's up to or if I'll ever find Palomar. Sometimes I hear people complaining that they don't know where to start. Just jump in! Keep going if you like it and fuck off if you don't. This is comics.

Providence by Alan Moore + Jacen Burrows

Brilliant unpacking and resetting of H.P. Lovecraft, trauma, denial and xenophobia.

Urstory by Amy Kuttab

Conjures the timeless dustlight of childhood.

Late Bloomer by Maré Odomo

Holistic record of life. Euphoric.

Ancestor by Malachi Ward + Matt Sheean

Turned me inside out.

Sunny by Taiyo Matsumoto

Heartbreaking.

Super Powers by Tom Scioli

Comics and psilocybin. What's the difference?

#25 and Mr. A #18 by Steve Ditko

New Comic Day.

Scab County by Carlos Gonzalas

I love the way this guy tells a story.

Mostly Saturn by Michael DeForge

I think this may be the first DeForge comic I've read all the way through. Obviously his stuff is visually brilliant, but to my eyes, all his comics (the ones I've tried to read) amount to a chromatic tribute to ennui... which isn't my thing. I may reread Mostly Saturn and see it as another tedium trophy, but honestly I've been too scared because the result of that first reading was ecstatic! I feel this comic is the first true "Literary Comic." It's got this braided, experiential abstraction thing going on that transcends all the usual comic language bullshit. This may be a complete game changer.

Brian Nicholson:

Top five comics of 2016, offered unranked

Big Kids by Michael DeForge, Drawn And Quarterly

There are a couple of things that reoccur in Michael DeForge comics. The first is plots about bodily transformation. The second is that, from story to story, there are changes in the formal language, not just of the storytelling, but in the approach to a figure, working through new ways to cartoon that most identifiable form. Even though the overwhelming majority of these comics have been very very good, the minor breakthrough of Big Kids is that, by focusing on a narrative of the transformation of the narrator's perception, the trend in DeForge's art, towards a more two-dimensional sense of the picture plane, away from depictions that feel grounded in three-dimensional space, can here dive even deeper into abstraction while the narration remains present in intimate emotional reality.

If DeForge's other comics can be considered body horror, or likened to early Cronenberg, this comic is more like a queer take on the 1998 film Pleasantville, by way of They Live. While those films use color and black-and-white to refer to different levels of "reality," DeForge sticks to color throughout, but instead uses a more distended and abstracted cartooning of the human figure as a metaphor for coming to terms with a deeper and stranger world. It's a narrative of self-acceptance, about growing into a mature person rather than remaining a stunted child. While the narrative feels like a metaphor for hallucinogen-induced revelations, drugs, alongside sex and anarchist anti-cop politics are present as plot elements from the very beginning. The arc doesn't begin at a place of presumed "innocence," but rather an adolescent's cynicism. The shift in the drawing is about going beyond the recognizable, the understood and agreed upon, to depict fresh feeling, a new awakening. Through the narrator's lens, we see things we haven't seen before, and are told they are depictions of everyday occurrences. It's a new way of being alive to the commonplace. The conclusion of the book, the narrator's caption of "I felt a lot of things," should be echoed in the understanding reader.

Band for Life by Anya Davidson, Fantagraphics Books

One of the immediate pleasures of comics is their accessibility, both in the easy understanding they offer to a reader, and for how the cheapness of the materials needed to make a comic allows for underrepresented viewpoints to be heard. Occasionally, a comic comes along that is funny and true in a way that nothing else has been allowed to be, depicting a worldview unarticulated elsewhere. Anya Davidson's Band for Life is both indebted to her own autobiography in the noise-rock underground and extends a deep literary and comedic empathy towards all marginalized people. The cartooning language is rooted in John Stanley, Milt Gross, Archie comics, the most accessible work there is. It's a character-driven comedy for people who are not going to see themselves and their struggles depicted anywhere else.

In collecting a strip originally serialized online, it becomes clear how many characters there are in the narrative, how distinct they are from each other, and how much thought has been put into giving everyone a consistent backstory, and showing how these fully realized figures can be in conflict but still be depicted sympathetically. Using a Simpsons-like approach to building strips around people previously depicted as incidental supporting characters, in time it depicts a world of music-making more inclusive than most arts scene within the real world, an act of utopian idealization that's a testament to Davidson's imagination in the face of a widespread lack of it.

Shortly after publication, the way of life the book depicts would begin to feel actively endangered. In a 2016 where the awful outcome of Trump's election was followed by the tragedy of the Ghost Ship fire in Oakland, and the white supremacist alt-right mobilized themselves to use complaints about fire codes to target live-art spaces to evict people from homes on the premise that these are places where radical leftists congregate, this book documents the way people's everyday lives can be an act of resistance, even if they are primarily fighting to have the energy to make music against all the other pressures in their lives. The climax of the book, an extended sequence that didn't previously appear online, shows how the band came to initially form. By using this flashback structure, the point is larger than just "life goes on." The comic's talking about a noise-punk band, rather than activism, and is a comedy rather than a political tract, but the book's world building-via-digression allows the book to make the cogent point, denied by the self-interest-obsessed we must collectively overcome, that disparate people can come together to organize into a unit more powerful than themselves individually.

Pushwagner, Soft City, New York Review Comics

This is a gorgeous visionary work, initially drawn in the 1970s, then lost, only to be rediscovered a few years ago, and now finding publication through an English-language publisher. The drawings are massive, composed around repetition, grids, a depiction of a mechanized world. The line flickers with the inconsistencies of real human life. Adults are drawn in a simplified manner, redolent of children's drawings, while the infant child is rendered deeply enough for us to know we are seeing this doomed world with its eyes. It has this wide-eyed view of the world, taking in cityscapes in all their dehumanizing detail. It's insane that this book exists, as everything that makes it remarkable, how fraught and anxious it feels, the scale of it, the ambition of it, how much energy is being dedicated to the capture of tedium, feels like it should work against the artist having the focus to complete it. There's a tension created between seeing some of the best drawings you'll see all year and becoming bored at seeing page after page depicting long sequences of nothing happening, reminiscent of the way that humans becoming bored of the beauty of the natural world led to a desire for the comforts of technology which then constitute the soul-deadening effect the book describes. It feels remarkably ahead of its time, its masterful one-point perspective and slightly quivering line feeling like a mixture of alien observer, infant child, and security camera shooting in 70mm. Filmic analogies would compare it to 2001, Jacques Tati, or Koyaanisqatsi. The pages create their minimalist score out of the reader's gasping. Ah. Ah. Awe.

Abner Dean, What Am I Doing Here, New York Review Comics

When this book was first published in 1947, it spoke a recognizable language in an unfamiliar way. There would've been some precedent, at least, to those familiar with gag cartoons. The lines are smoothly swooping, the black and white shading done with graceful wash. Still, the characters are naked, but without genitals. The worlds depicted in each panel have no grounding in recognizable situations. The punchlines offer explanatory context only by the fact that the set of feelings they refer to seems to be illustrated by the drawing. There was nothing like it then, and nothing like it followed. It feels like fine art speaking a gag comics language. It ends up aging better than any gags from that era I've seen. If the gag panels in a 1950 or 1960 Playboy cartoon feel dated in their gender politics, the naked-but-without-genitals figures here seem to speak only a language of romantic intrigue defined by longing and loneliness, and feel profound and timeless.

Eleanor Davis, Libby's Dad, Retrofit Comics

Working with the single issue format for a short story, rather than contributing to an anthology, Eleanor Davis stretches out here in ways that allow for changes in tone larger than in any individual story she's told before. There is a subtle, pitch-perfect control in the way the pages here slowly fill up with the color blue, depicting the shift from day into night by delineating more and more of the characters' surroundings. The world becomes more defined by darkness, the young characters idyll being disturbed by the reality of the world they're living in insinuating itself. The things that can be accepted in daylight can become utterly horrifying once the sun sets. The tension and sense of unease that develops is stunning. It's not a horror comic, but the book hinges on a moment where Davis communicates her characters' fear, and so demands a level of control from her over her audience that her previous work, based more on a sort of affectless tone of neutrality, didn't. However, that moment of terror is only used to get to the conclusion, where this open-ended voice returns, and we are meant to read against the characters' interpretation of events. We've been shown that the sense of safety felt in the daylight isn't necessarily true, because living with fear every night slowly takes it toll, and just because we survive doesn't mean the darkness should be denied as a force that defines people's lives.

Tahneer Oksman

There were many books published this year that I loved and that I couldn't fit onto a top-five list. Suffice it to say, for the purposes of this end-of-year exercise I decided to include works that I know I will return to again and again, and those that in some way (formally, emotionally, intellectually) surprised me.

Becoming Unbecoming. Una. Arsenal Pulp Press.

First published by the UK's Myriad Editions in 2015, Una's Becoming Unbecoming tells the story of a young girl growing up in Northern England in the late 1970s against the backdrop of the brutal murders of thirteen women (including many sex workers) by a serial killer eventually dubbed the Yorkshire Ripper. The book carries its central themes--of epidemic violence against women and the growing pains of adolescence--over a gently narrated landscape that continually changes shape to accurately capture how the personal and political always dynamically interact.

We All Wish for Deadly Force. Leela Corman. Retrofit Comics & Big Planet Comics.

Like the gorgeous and painful image gracing its cover, Corman's We All Wish for Deadly Force packs an extraordinary emotional punch. The autobiographical pieces contained in this slim volume, adapting, at times, mythical, biographical, and surrealist slants, tell of longing, loss, rage, and bemusement, all from an incisive, capacious narrating point of view. It would be difficult to overstate the emotional grace of these short comics.

Gulag Casual. Austin English. 2D Cloud.

English calls this book his "first real stab at making art in comics," and it is quite a tour de force. Reading through Gulag Casual is something like a cross between flipping through an exceptional artist's private, experimental sketchbook and looking at pieces of art hung up in a Chelsea gallery. The colors, shapes, textures, and narrative snippets are unexpected, and the images and moods depicted throughout somehow appeal through their gruesomeness.

After Nothing Comes. Aidan Koch. Koyama Press.

After Nothing Comes includes a selection of six zines composed by the artist between 2008 and 2014, appended by a brief interview between Koch and Bill Kartalopoulos. This is another collection of experiments: landscapes, geographic and bodily, are pieced together by an artist dabbling in both naturalistic and abstract drawing styles. The pieces contained are image-word play, briefer and longer poems and narrative bursts examining the nature of disconnectedness and loneliness.

The Arab of the Future 2. Riad Sattouf. Metropolitan Books.

Like the first collected volume of his series, Sattouf's The Arab of the Future 2 is a chronologically narrated story of a recalled upbringing. In this book, Sattouf describes a single year in his life (1984-1985), when he was just six and living in the small Syrian village of Ter Maaleh. Through his careful selection of detailed scenes from childhood shaped by sudden shifts in coloring, Sattouf viscerally evokes everything from the moments of first learning to read the words in his beloved Tintin comics to early imaginings of the sounds his toys made as they moved around at night.

Joe Ollmann

Here's my list, in no particular order, probably forgetting stuff I loved.

All of Jillian Tamaki’s work on the Hazlitt site.

Patience by Dan Clowes

Crickets #5 by Sammy Harkham

The Arab of the Future by Riad Sattouf

Beverly by Nick Drasno

Sean Rogers

I filed a top five for 2016 with the Globe and Mail, where my picks were Blutch’s Peplum, Chester Brown’s Mary Wept over the Feet of Jesus, Anya Davidson’s Band for Life, Julie Doucet’s Carpet Sweeper Tales, and Aidan Koch’s After Nothing Comes. Here are another five that are every bit as good:

Love Nest by Charles Burns (Cornélius). Burns perfects the comic strip as virus—the idiom itself seems infected, contagious, incurable. Like Jack Kamen boiled down and made black and hard as obsidian.

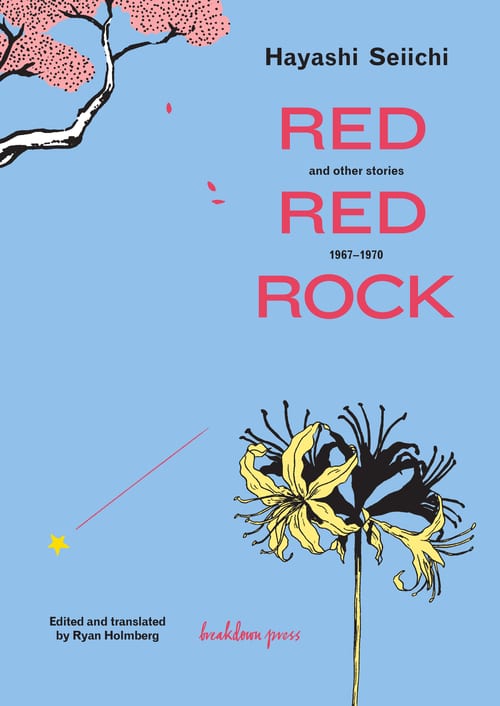

Red Red Rock and Other Stories 1967-1970 by Seiichi Hayashi, edited and translated by Ryan Holmberg (Breakdown Press). Even with Holmberg’s best-in-the-game contextual notes, I’m not always sure what’s going on in Hayashi’s elliptical allegories and psychodramas at any given moment—but, my God, those moments. Some favorites: a rural community sprouting sleek skyscrapers, a girl’s small feet in a faceless man’s brogues, the silhouettes and snow as a woman pleads with the ghost of her husband, all of it haunted and corrupted by memories of war.

Sir Alfred No. 3 by Tim Hensley (Pigeon Press). Along with Deitch’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams, Blutch’s So Long Silver Screen, and Oshima’s Ninja, this is one of the great cross-pollinations between comics and cinema. Hensley’s limber wordplay is largely absent (though on location in the Alps, Hitch retches: “Pabst!”), but his cartooning and joke-telling have never been more tightly controlled.

Ganges Number Five by Kevin Huizenga (self-published). This one’s about everything—work and death and love and religion and the origins of the Earth—but it’s still remarkably humble and patient and curious and kind. Huizenga maps out what it feels like inside your head better than anyone.

“Kanibul Ball“ by Lale Westvind, from Kramers Ergot 9 (Fantagraphics). Westvind locks onto the maniac frequency that was humming away through the Golden Age, Kirby, the undergrounds, Pettibon—some Jungian, cosmic shit that rips out again here, resplendent and brutish and powerfully American.

James Romberger

Tim Hensley, Sir Alfred #3, Fantagraphics Books

Dan Clowes, Patience, Fantagraphics Books

Kevin Huizenga, Ganges #5, Fantagraphics Books

Mike Mignola, Hellboy in Hell, Dark Horse

Anya Davidson, Band for Life, Fantagraphics Books

Hugo Pratt, Corto Maltese: The Ethiopian, Eurocomics/IDW

Chester Brown, Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus, Drawn & Quarterly

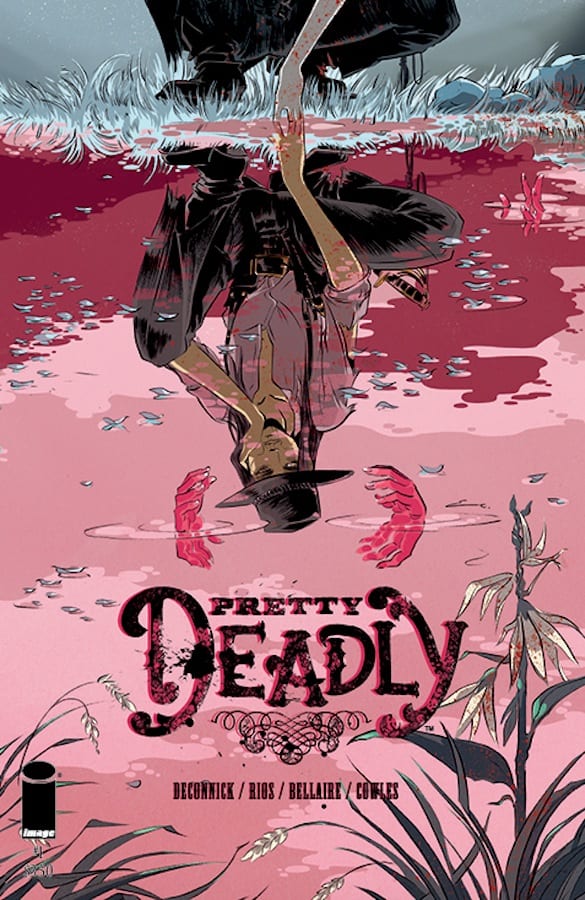

Kelly Sue DeConnick/Emma Rios, Pretty Deadly, Image Comics

Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, Love and Rockets #01, Fantagraphics Books

John Arcudi/Tonci Zonjic, Lobster Johnson: Metal Monsters of Midtown, Dark Horse

Katie Skelly

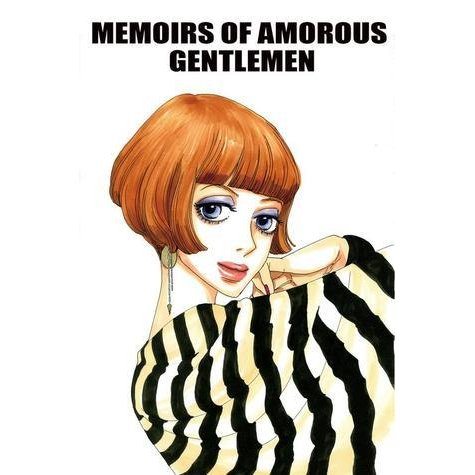

Let’s start with Memoirs of Amorous Gentlemen by Moyoco Anno. There’s always an element of humanity removed from Anno’s characters. Somewhere in her super deliberate line that gives way to sharp ribcages and scalpel-precise haircuts, there’s also a ravenous urge to consume and fuck. Anno is never really one for middle ground, although it doesn’t rob her stories of personality. Every now and then some funny or playful sensibility can sneak its way in, but to see Anno only for this would be a massive oversight. Speaking of bobbed hair biches, The Complete Crepax: Dracula, Frankenstein, and Other Horror Stories (Volume 1) is the book of revelations. (Full disclosure, I wrote a short essay for this book!) It’s an amazing excerpt from the breadth of Crepax’s career, and a clever move to start with his sojourns into (and perversions of) the horror genre. Like Crepax, Sarah Horrocks works in a language wholly her own and wholly alien to today’s comics tendencies in her series The Leopard, issue 3 of which came out this year. Forgive me, as I know she’s my dear friend and podcast partner, but who else is doing straight body count murder comics right now? (Note: please don’t actually tell me.) Nasty stuff. Conversely, Gina Wynbrandt serves up soul-murder with her humor compilation Someone Please Have Sex with Me, most impressively, resisting the self-affirmations most of the mills crave. But who knew the most life-affirming work this year would be (a) from Julia Gfrörer and (b) about kissing your loved ones goodbye in the plague? It’s there in Laid Waste: see if you don’t come away with a smile after that one, in the same way you feel a wash of positivity after seeing a film like Martyrs. And finally – give me some leeway on this one as I know it came out in late 2015, but my love of it carried through 2016 and nothing else has struck me the same way since: “Queue” by Dilraj Mann (Island #3, ed. Brandon Graham & Emma Rios). Mann swaddles his gelatinous figures in giallo gel lights as they maneuver through the tedium of hookup culture. I like how Mann does alienation through color rather than dialogue or emotional expression, and I love how his figures dominate the panels. There’s a thickness to his figures reminiscent of Jonny Negron but an agency that’s his own. And that was my year!

Leslie Stein

Last Look- Charles Burns

Beverly- Nick Drnaso

Disquiet - Noah Van Sciver

Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus - Chester Brown

Nicolas - Pascal Girard

Tucker Stone

5. Red Team Double Tap Center Mass #1 by Garth Ennis

Dude finally changed his haircut, nice

4. Johnny Red #6 by Garth Ennis

Who is that weaseling over there by my garbage cans OH SHIT IT’S HITLER

3. Six Pack and Dog Welder Hard Travelin Heroez #1 by Garth Ennis

Oh man, his kid's faces are so jacked up

2. World of Tanks #1 by Garth Ennis

"Cor blimey", a spot of tea, AND a fucking tank?? 'nuff said

1. Red Team Double Tap Center Mass #4 by Garth Ennis

“Shoulda cleared the room, cuz here comes the boom” —Billy Joel.

Whit Taylor

This is a list of my favorite comics and minicomics from 2016.

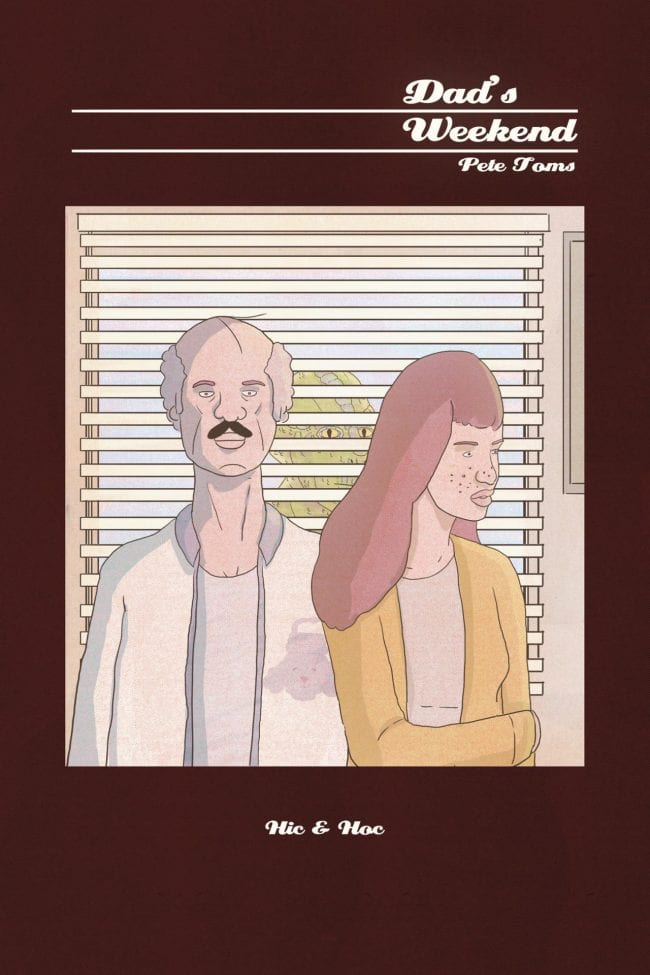

Dad’s Weekend, Pete Toms (Hic & Hoc)

Blammo #9, Noah Van Sciver (Kilgore Books)

House of Women III, Sophie Goldstein (self-published)

Burrow, Marnie Galloway (self-published)

Self, Meghan Turbitt (self-published)

The Unofficial Cuckoo’s Nest, Luke Healy (self-published)

Summerland, Paloma Dawkins (Retrofit)

Diana’s Electric Tongue, Carolyn Nowak (Shortbox)

Your Black Friend, Ben Passmore (Silver Sprocket)

Over Ripe, Sophia Wiedeman (self-published)

Our Mother, Luke Howard (Retrofit)

Frontier #11, Eleanor Davis, (Youth in Decline)

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, Annie Murphy (self-published)

Sir Alfred No. 3, Tim Hensley (Fantagraphics)

Paul Tumey

My Favorite Thing is Monsters - Emil Ferris

A complex, wrenching, beautifully drawn magnum opus from a gifted and experienced artist new to the scene -- worthy of the "graphic novel" label in all senses of the word. Delayed until February, 2017, this was supposed to be a 2016 book -- and for me, it was: I was able to get a review copy in late October, and was blown away. I reviewed it already here. You're gonna love this one when it comes out.

Si Lewen's Parade: An Artist's Legacy - by Si Lewen, introduced by Art Spiegelman

Soldier-artist Si Lewen's 1957 wordless story about the glorification of war and the cost to humanity is timeless and speaks to us as much, if not more, today than ever. Art Spiegelman discovered and befriended Lewen through his work on his 2014 "Wordless!" slide lecture/jazz performance tour. This edition presents Lewen's story, with newly discovered "outtakes," in an accordion-fold format, perfectly mirroring it's content. This edition is really two books in one. On the reverse side of the work, Art Spiegelman has written a lengthy, fully illustrated introduction and interview that expands our understanding of Lewen as a warrior turned artist, bravely committed to his art and vision. The color images of his paintings included in the "ghost book" on the reverse side of the accordion book are simply stunning. Lewen died, at 97, a few days after Spiegelman presented him with one of the first copies produced. Ultimately, this book offers a parade of at least three compelling stories: Lewen's parable, his life story, and the touching friendship between him and Art Spiegelman.

Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White by Michael Tisserand

The first full-length biography of the artist who many, including me, consider to be the greatest comic strip creator in Western culture. In addition to learning the fascinating details of a major cartoonist's life and career in this superbly written narrative, I came away from the book with a much deeper grasp of Herriman's work, especially the monolithic Krazy Kat.

Dick Tracy: Colorful Cases of the 1930s, edited by Peter Maresca

The first years of the landmark, super-bizarre comic strip are surveyed in sumptuously restored color Sunday pages reproduced in their original size and colors. The spot-on curation selects four different continuities, and a fascinating selection of other pages, all buttressed by clear-eyed, rigorous scholarship. I would place this volume among my favorites even if I wasn't a contributing writer, in a small way, to the introductory material. The importance of reading the great American newspaper Sunday comics in their original sizes and colors cannot be overstated -- it is essential for gaining the true experience as the artist intended. In this carefully composed book, we get to see Gould's signature visual style and bizarre vision of the world take shape in front of our eyes, which is thrilling.

Highbone Theater by Joe Daly

Daly did it again. I regard his Dungeon Quest series and The Red Monkey Double Happiness Book to be among the funniest, most engaging modern comics I've read. Highbone Theater, a modern day, slacker magical realist version of the hero's journey, delivers the goods again. I laughed out loud many times, and I wasn't stoned. Like the herbs and chemicals so many of his character's imbibe to attain mystic visions, Daly's books take my mind to new places, and I love that about his work.