This article originally appeared in The Comics Journal Library: Jack Kirby, published in 2002.

It was Jack Kirby, perhaps more than anyone else, who taught us how to imagine the behavior of superheroes if they inhabited the world alongside us. By 1970, the comic books we read had come to revolve around Kirby -- his vision, his style, his skill -- like satellites around a stellar body. But the mid-1980s found him at the center of a struggle that threatened to transform the real world of the comics industry just as radically as his imagination had transformed the aesthetic conventions of the superhero genre.

The crux of the dispute was the insistence of Marvel Comics, Kirby's longtime creative home, that he sign away all rights to the Marvel-published characters he had created. As a coercive gesture, the company informed him that it would hold hostage all Kirby original art in its possession until he agreed to sign a special release form that was required of no other Marvel freelancer. Kirby refused to sign the document, and Marvel, in turn, refused to return his original art, and the resulting stand-off that played out before the rest of us was both disillusioning and inspiring. On the one hand, for those who still cherished memories of the 1960s as a kind of Camelot, in which "King Kirby" and "Stan the Man" presided over a happy bullpen, this was a particularly sour epilogue. Marvel's corporate lawyers could have chosen no more effective way to spit on the ruins of the House of Ideas -- the House that, as they say, Jack built. But on the other hand, the conflict also presented a vision of comics creators, fans and industry media coming together to tip the balance of power against a corporate giant.

The crux of the dispute was the insistence of Marvel Comics, Kirby's longtime creative home, that he sign away all rights to the Marvel-published characters he had created. As a coercive gesture, the company informed him that it would hold hostage all Kirby original art in its possession until he agreed to sign a special release form that was required of no other Marvel freelancer. Kirby refused to sign the document, and Marvel, in turn, refused to return his original art, and the resulting stand-off that played out before the rest of us was both disillusioning and inspiring. On the one hand, for those who still cherished memories of the 1960s as a kind of Camelot, in which "King Kirby" and "Stan the Man" presided over a happy bullpen, this was a particularly sour epilogue. Marvel's corporate lawyers could have chosen no more effective way to spit on the ruins of the House of Ideas -- the House that, as they say, Jack built. But on the other hand, the conflict also presented a vision of comics creators, fans and industry media coming together to tip the balance of power against a corporate giant.

In a real sense, the success of Kirby's creative efforts were the very thing that made Marvel's lawyers see the desirability of separating him from his creations. In large part due to his work, the comics industry, and in particular, the superhero genre had gone through a revival in the 1960s -- so much so that the industry's traditionally careless attitudes toward copyrights and written contracts began to change. It wasn't just monthly comic books that were at stake any more; it was the vast ancillary potential of licensing and merchandising the content of those comics.

Therefore, when the copyright law changed in 1978 to identify work for hire as a relationship defined by written contract, the major companies rushed to make sure their paperwork was in order. New, very specific contracts were issued that were careful to cover the exploitation of comics characters and concepts in other media.

When Kirby got his first look at Marvel's new contract in 1979, he was very aware that the value of his creations had extended beyond the pages of comic books because he had just come back from a months-long stint overseeing the animation of Fantastic Four cartoons. His workload on the comics had been cut back to allow for his animation work, but as the TV animation season ended, he was scheduled to resume his former pace, writing and drawing some 15 pages a week for Marvel. Instead, he balked at the new contract and departed Marvel for good. He told The Comics Journal then, "Maybe this is the right time of life to try other things."

Kirby's departure may have been a consequence of the new contract or he may have planned to leave anyway and saw no reason to sign away rights to a company he no longer planned to work for. In any case, it was the beginning of an estrangement that was to culminate in a highly publicized showdown in the mid-1980s.

Kirby was not the only creator bothered by the contracts that had appeared suddenly in 1979. Although the documents did little more than spell out explicitly the terms that had been vaguely presumed to be in place all along, there was something about seeing their bosses' dominion over the fruit of their labors described so baldly in black-and-white that made many creators think twice about acquiescing. Mike Ploog walked off the job in the middle of a two-part Weirdworldspecial. Neal Adams exhorted his fellow artists not to sign their rights away. And creators began holding meetings and talking seriously about unions and organizing.

DC, though guilty of fierce union-busting practices in the past, had gradually come a long way toward improving its relations with creators. It had acknowledged the right of creators to the return of their original art as early as 1973 and, in 1978, that right was explicitly stated in its creator contracts. It later further mollified creators by instituting a royalties system by which all creators were paid a small share in future profits resulting from reprints and adaptations into other media.

Marvel followed DC's lead with respect to returning art and paying royalties -- or incentives, as Marvel called them -- and both companies were already routinely returning new originals each month by 1976. Generally, pencilers received two-thirds of the pages of a particular issue, while inkers received one-third. DC industriously went through its backstock of original art, cataloging it and mailing it to artists. Its policy, as explicitly stated in the 1978 contracts, called for DC to return new original art within a year or compensate the artists by paying an amount equal to the originally paid page rate. If original art was lost and then found after the artists had been compensated, the art was sent to the artists in addition to the already paid compensation.

Marvel, on the other hand, held onto its backstock even as it began returning new original art. Some artists, such as Jim Steranko and Joe Sinnott, had been able to get some or all of their art back, but for the most part, all original Marvel art had gone into storage. The question of backstock was not one that Marvel wanted to see raised. Its stockpiles of original art were reportedly in such disarray that cataloging and organizing them promised to be a mammoth undertaking. There was also the fear that large quantities may have been lost, pilfered or given away according to whatever whims had prevailed in the absence of consistent policies. According to Irene Vartanoff, who was assigned to catalog Marvel's backlog of original art in 1975, the company's storage facilities were piled high with chaotically and precariously stacked art envelopes dating as far back as 1960. It took Vartanoff a year to organize the warehouse and catalog its contents. She remained in charge of the facilities until 1980, and during her tenure, she said, it was common for Marvel executives to give away pages of original art as incentives to business partners. Some time after Vartanoff left her position, pages of original art were moved from the warehouse and kept near a snack room next to a freight elevator, according to Kirby's former original art agent Greg Theakston. Theakston said he had seen for sale by dealers original art that had been taken from Marvel during this post-1980 period.

When Marvel decided in 1984 to offer the return of its backstock of original art to creators, its offer to Kirby was able to account for only 88 pages of Kirby art out of a total of more than 8,000 pages that the artist had done for Marvel between 1960 and 1970 -- approximately one percent.

As Marvel had returned new original art from 1976 on, artists had been required to sign brief release statements, about four lines long, and the 1984 offer to return the stored original art was also accompanied by the requirement that a one-page release form be signed. The form described the art return as "a gift" from Marvel to the creators. By signing the form, the creators agreed that the art had been work for hire and that Marvel was "the exclusive worldwide owner of all copyright" related to the art. Creators were required to grant Marvel the right to use the artists' name and likeness in promotions.

The form's language was reminiscent of the contracts that had been instituted in 1979, and some creators objected to both the wording and the coercive tactic of tying it to the return of original art. Neal Adams told the Journal at the time, "Anybody who signs that form is crazy.... You dangle a carrot in front of the artists' faces, saying, 'If you want your art sign this form.' It's not true; you don't have to sign it."

Most artists signed the form and received their art, and even Kirby said he would've been willing to sign it, but that was not the option that Marvel offered him. If some artists had found the one-page release objectionable, Kirby was outraged to find that he and he alone had been sent a four-page document that multiplied the obligations of the creator and the rights claimed by the publisher. Even the nature of the "gift" was qualified in the form sent to Kirby. Where the one-page form offered creators "the original physical artwork," Kirby's form offered "physical custody of the specific portion of the original artwork." Always careful not to acknowledge that the artists had any right to the art, the one-page forms made clear at least that the artists would be the owners of the art once the "gift" had been accepted. The gift to Kirby, however, was nothing more than the right to store the art on behalf of Marvel. Though it would be in his possession, there was nothing that Kirby would be allowed to do with it: "The Artist agrees that it will make no copies or reproductions of the Artwork, or any portion thereof, in any manner, that it will prepare no other artwork or material based upon, derived from or utilizing the Artwork, that it will not publicly exhibit or display any portion of the Artwork without Marvel's advance written permission, and that it will not commercially exploit or attempt to exploit the Artwork or any material based upon, derived from or utilizing the Artwork in any manner or media, and that it will not permit, license or assist anyone else in doing any of the foregoing."

While Kirby was forbidden from so much as displaying the art in public, Marvel was to have ready access to it for whatever purpose it deemed desirable: "Upon Marvel's request, with reasonable advance notice, the Artist will grant access to Marvel or to Marvel's designated representatives to make copies of the portion of the Artwork in the custody of the Artist, if Marvel so needs or desires such copies in connection with its business or the business of its licensees." The artwork was also subject to "revision" and "modification" at Marvel's discretion.

As worded, the form would not even allow Kirby to sell his own original art, since that would constitute commercial exploitation. And in any case, he would have nothing to sell but the "physical custody" of the art. He was allowed to "transfer to another person the physical custody of the portion of the Artwork being transferred to the Artist by Marvel," but only if the new custodian signed the same four-page document that had been presented to Kirby.

The long form addressed the question of copyrights in a manner similar to the short form, but in greater detail and with greater care to ensuring that Marvel retained "in perpetuity all other rights whatsoever." In airtight language, the formed claimed for Marvel all copyrights that belonged to the company under the law, but in the event that there were rights that Marvel was not entitled to under the law, it insisted that the artist surrender those as well: "To the extent, if any, that all copyright rights and all related rights in and to the Artwork are not owned by Marvel as provided above by operation of law, the Artist hereby irrevocably grants, conveys, transfers and assigns its entire worldwide right, title and interest therein to Marvel."

To Kirby, who publicly disavowed any wish to challenge Marvel's copyrights, one of the most troubling aspects of the document he was given to sign concerned his right to "assist others in contesting or disputing, Marvel's complete, exclusive and unrestricted ownership of the copyright to the Artwork." He feared this passage would prohibit him from testifying on behalf of any other creators who might contest Marvel's copyright claims or its claims to ownership of all original art done for the company. In fact, it forbade him from objecting even in private to the unfairness of the agreement that Marvel sought to impose upon him.

Even if Kirby had had no interest other than the safe return of his original art, the form offered him no assurances in that regard. Although only a fraction of the art Kirby had done for Marvel had been identified and collected for return, the form specified that in accepting the return of these 88 pages, Kirby was acknowledging that he was entitled to no other art in Marvel's possession: "The Artist acknowledges that he or she has no claim or right to the ownership, possession or custody, or any other right in, any other or different artwork or material presently in Marvel's possession, custody or control, and that Marvel may, if it so desires, transfer the custody of any other such Artwork or material to whomever it may in its sole discretion desire." In order to receive custody of the 88 pages, Kirby was being asked to relinquish all rights to the thousands of other pages of original art he had done for Marvel and to acquiesce to the disposal of the additional art in any manner that Marvel chose.

Kirby received the form in August of 1984 and, over the months that followed, he attempted to negotiate some form of compromise with Marvel Editor in Chief Jim Shooter, asking that a more thorough list be compiled of the original Kirby art in Marvel's possession and offering to send a representative to assist the company in cataloging the materials. Shooter refused all such requests, explaining in a Jan. 25 letter to Kirby that it would be "unfair" to single Kirby's art out for special treatment -- though he apparently saw nothing unfair in devising a release form that targeted Kirby exclusively. Marvel's position remained firm that the artist must sign the four-page document in its entirety or he would receive no art back.

In the summer of 1985, the standoff between Kirby and Marvel became public knowledge whenThe Comics Journal broke the story. The Journal not only reported the controversy, it pursued the story tenaciously over the next several months, eventually taking up advocacy of Kirby's rights in the matter as a crusade. In an editorial entitled "House of No Shame" in TCJ #105 (February 1986), TCJ Editor/Publisher Gary Groth wrote, "You don't need to have grown up reading Jack Kirby's work to recognize that Marvel's treatment of him is criminal." The editorial was part of a Kirby-themed issue "dedicated to swaying Marvel's heart, if indeed the corporation has one." Partly as a result of the Journal's efforts, Kirby became a comics cause célèbre and Shooter and Marvel found themselves in the middle of the worst public relations disaster in the company's history.

In an interview with Kirby in TCJ #105, the artist said, "All I know is that I own my drawings, but they've got them, and they know that I own them. They know, and they're holding them arbitrarily. In other words, they're grabbers. They'll grab a copyright, they'll grab a drawing, they'll grab a script. They're grabbers -- that's their policy. They can be as dignified as they like. They can talk in lofty language, although they don't usually... not to me [laughter]. They can act like businessmen. But to me, they're acting like thugs."

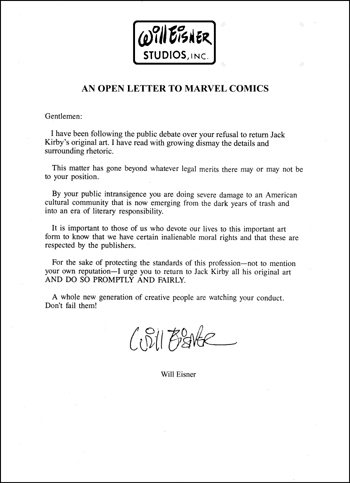

The controversy became a common topic of comics convention panels, several prominent comics professionals, including Adams, Frank Miller and Garry Trudeau, spoke out on behalf of Kirby, and even some non-comics media picked up on the story, including Los Angeles television and radio stations. A July 24, 1986 episode of ABC's 20/20, however, profiled Marvel's accomplishments without mentioning Kirby, let alone his dispute with the company.

Of the many letters on the subject that flowed into the Journal, only one defended Marvel's position. In an essay in TCJ #105, Miller noted, "Several voices have been raised on Kirby's behalf. Many more voices, much quieter, have shown that a great deal of creative ingenuity is being devoted to the invention of excuses for professional cowardice." But despite the professional risks of defying the corporation, when the Journal composed a petition urging Marvel to unconditionally return Kirby's original art and circulated it among 200 individual comics professionals, all but 50 had signed it by August of 1986.

Marvel initially remained intransigent. Artist Kenneth Smith commented July 6, 1985 at a Dallas Fantasy Fair panel, "It strikes me that by threatening to harden its stance if there is public criticism of its posture, Marvel is not displaying the mentality of adolescents; it's displaying the mentality of Shiite terrorists, who have managed to take hostage some valuable original art, as well as abstract legal rights of the artists involved."

Even competing publisher DC Comics sent the Journal an open letter in February of 1986 scolding Marvel for failing to follow DC's ethical example. There was more than ethics, however, behind comics publishers' decision to relinquish any claim to ownership of original art. If a publisher were to officially take possession of the physical art that it reproduced in comic-book form, then, under the law, the transaction would involve more than the assignment of publishing rights; it would constitute the sale of an object. As such, the transaction would obligate the publisher to pay sales tax on the original art. No one in the comics industry had been doing this and for longtime publishers like Marvel and DC to insist on ownership of original art would've meant embracing a disastrous debt to state governments. Marvel's release forms, with all their carefully phrased references to "gifts" and "physical custody," sought to have it both ways, implying ownership without directly claiming it.

In July of 1986, Marvel Vice President of Publishing Michael Z. Hobson issued a public statement telling the company's side of the story: "Marvel has long been willing to give Mr. Kirby such artwork in accordance with its artwork return policy. In fact, Marvel returned hundreds of pages of artwork to Mr. Kirby under its artwork return policy during his last period of employment between 1976 and 1978, and Mr. Kirby signed all release forms submitted to him at that time. Since that time, however, Mr. Kirby has refused to acknowledge Marvel's ownership of the underlying copyright in the artwork remaining in Marvel's possession, and Jack Kirby alone has made adverse ownership claims to some of the underling characters which Marvel is presently publishing. These ownership claims by Jack Kirby were made despite the fact that Jack Kirby previously entered into several agreements with Marvel in which he acknowledged Marvel's proprietary rights in the artwork and underlying characters, and for which Mr. Kirby was fully paid by Marvel. Marvel nevertheless received a series of letters from Mr. Kirby's attorneys during the past four years asserting claims of copyright ownership. As a result of this correspondence, Marvel insisted that in order for Mr. Kirby to receive the artwork earmarked for him, Mr. Kirby would have to sign a longer, more detailed release than the release given to other artists. Mr. Kirby refused to do this and the matter has been at a standstill."

If Kirby had refused to sign the first of the work-for-hire contracts that he had been presented with in 1979 and had not worked for Marvel since, what was the nature of the "agreements" Hobson claimed were already in place? According to writer and longtime Kirby confidante Mark Evanier, Kirby had signed, in the 1960s, an affidavit that related only to Captain America, and in 1975, an employment contract that did not address copyrights. He had also apparently signed a release in 1972, and it was this document that Evanier believes formed the basis of Marvel's claim to a copyright agreement.

Marvel's statement suggested that the conflict was moving closer to resolution as Kirby clarified that he was not interested in challenging Marvel's copyrights. Marvel, for its part, was willing to drop the four-page release if Kirby would sign the short form. By this time, Marvel was apparently eager to return the art pages and put the whole fiasco behind it, but among the details that remained to be worked out was Kirby's demand that he be granted creator credits whenever Marvel and its licensees used his characters. In his statement, Hobson said Kirby had demanded that he be identified as the sole creator of such characters as Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four and the Hulk. Roz Kirby told the Journal her husband would not sign the short form until the art that was to be returned was identified in its entirety. The credit issues had been raised, she said, due to the absence of Kirby's name in the creator credits of past projects, and their demand was only that Kirby be among those credited.

Kirby and Shooter met for the first time in person on Aug. 2, 1986 at the Comic-Con International in San Diego, when Shooter passed near Kirby's table and artist Jim Starlin motioned the editor in chief over. The two spoke for only a couple of minutes. Kirby's wife, Roz, later said, "I just told him what we wanted and [that] we were going to stand firm."

At a Jack Kirby Comic-Con panel that same day, Groth stated that Marvel owed Kirby at least three things: Return of his original art or monetary compensation when art had been lost or stolen, creator credits for characters Kirby had created or co-created, and an apology. The audience applauded.

Shooter, who had been sitting in the rear of the room during the panel, remained afterward to respond to questions from fans. Shooter explained that he had persuaded his superiors to begin returning the original art backstock to creators, but "before we were able to begin returning it, while lawyers were reviewing the situation, is when we started to receive claims of copyright ownership from Jack Kirby. The claims of copyright ownership that came in and the way the demands were made made it very difficult to return artowrk, because any return of artwork, the way the demands were phrased, would be a tacit admission of guilt."

According to Evanier, Kirby had made "a couple of threats," suggesting that Marvel's copyrights might be vulnerable to challenge, in the course of correspondence regarding creator credit issues. "They kept threatening him and he kept threatening them," Evanier told the Journal. "It was the only way he could get their attention. And somebody at Marvel over-reacted." Kirby's comments had only been aimed at gaining some leverage in the dispute over creator credits, according to Evanier: "He had decided in the early 1970s that, financially and emotionally, the copyright issue was not a fight he was prepared to fight."

At a "Marvel Then and Now" Comic-Con panel, on the question of original art, Shooter stated unequivocally, "We own it entirely."

The final resolution came in May of 1987, nearly three years after Marvel had first begun returning original art backstock and nearly 30 years after it had begun accumulating the art. Marvel had dropped its demand that Kirby sign the four-page document and had amended the short form to address his concerns. Details of the amendments were not made public, but Kirby's lawyer, Greg Victoroff, told the Journal, "Jack got just about everything he wanted." The form was signed and the art was returned. The eventual tally of Kirby art Marvel had collected for return came to approximately 1,900 pages, still far short of his total output for Marvel but considerably more than the amount originally specified.

In the end, Marvel was so worn down by the controversy over its original art policies that it returned Neal Adams' art in May of 1987 without even requiring him to sign the short form.