It's time someone came out and said it—Chester Gould's Dick Tracy is bonkers. Stark raving crazy. But it's an American crazy—we feel at home in it.

From its flights of grand guignol violence—scenes of bloodshed, torture, suffering, starvation and mutilation—to its merger of clumsy comedy and grim police procedural; from its high-handed sermonizing to its moments of unexpected levity, Dick Tracy among the maddest achievements of American popular culture. This, perhaps, is why it so compels us.

What made—and makes—Chester Gould's work so damned compelling? There is much about Dick Tracy that has long been taken at face value, and never deeply explored. Gould's aggressive, angular art style, and his off-kilter visual juxtapositions, have gotten lip service from the art world, and from a handful of writers on comics whose viewpoints can outwit the trap of nostalgia. Its gallery of stylized caricature-villains is always mentioned, in mass media, with a mixture of awe and condescension.

There is much more going on in Gould's work—but it requires a devoted scrutiny. It asks its reader to pay close attention, to notice small, seemingly unimportant details and to accept and process arcane information, some of it inexplicable. Its voice is hugely eccentric, didactic and arrogant in its self-righteousness.

The oddness of Tracy was evident 50 or 60 years ago, to those who cared to look. The collagist Jess Collins' series of Tricky Cad pieces—witty re-assemblings of Gould's 1950s work that show an understanding of its native peculiarity—are evidence that at least one person, in this period of time, grokked the otherness of Tracy and celebrated it. Collins' collages are the funniest modern art a person could hope to encounter.

My favorite year of Dick Tracy is 1956. It can be read in the 16th and 17th volumes of the Library of American Comics' Tracy books. In addition to the sequences I'm about to discuss, these volumes include the “return of Mumbles” story-line, a manic Molotov cocktail of slapstick and grim comics noir. If you have been curious about Gould's work, but unsure how to approach it, '56 is the gateway year.

Gould blends two major story-lines of broken children, negligent parents and cynical, amoral men in a 12-month narrative freight train. Moments of stark melodrama, forensic science, intense police pursuit and a haunting, prolonged depiction of a character's loss of sanity (with resultant hallucinations) are components of an amped-up, balls-to-the-wall year of savant storytelling.

The year's first major story strand stars teen hood Joe Period, hired to woo a nightclub singer for a retired lawyer three times the woman's age. Singer and ex-lawyer are murdered by Period (along with an innocent parakeet), and the fleeing teen, smashed to near-death in an auto accident, ends up stuffed into a bass fiddle case and tossed on a moving freight train by two callous hoods. An alcoholic, disbarred doctor, now a tramp, nurses Joe back to health. His reward, too, is death.

Loony as this narrative sounds in retelling, it comes to life with the stylized, ritualized cartooning of Gould and his assistants. Gould was part of a front-line school of grotesque Chicago Tribune cartoonists. With the exception of Milton Caniff, all the Tribune's major cartoonist share a look and feel that contains ugly, misshapen elements. Even Frank King's lyrical Gasoline Alley has its share of this Trib house style—the oversized hands and feet of its quasi-naturalistic figures, and the outstanding visual repellence of its black characters.

It seems likely that the Tribune cartoonists were encouraged to follow this visual path. With revelatory sketches of Harold Gray and Frank King published in ongoing reprint series of these artists' work, it's evident that these cartoonists were capable of more sedate, less stylized illustration. Bigfoot Trib artists like Bill Holman and Ferd Johnson are easy on the eye, but have elements of distortion and grotesquerie in their work. The syndicate's lesser artists—Zack Mosely, Dale Messick, Carl Ed and Martin Branner, et al—are especially eccentric. Taken together the Tribune's comics roster seems to suggest that, in the syndicate's POV, comics had no need for the spit-and-polish of, say, the King Features Syndicate's strips.

As with all comics, the visual element is our first impression. Gould's artwork hews to, yet transcends, the Trib-grotesque school. It is a curious blend of big-foot cartooning, catalog illustration and synthesized pop-art realism. Gould is a true stylist. His stylistic signatures—heavy, bold lines, massed areas of black, nail-file cross-hatching—transcend his limited academic draughtsmanship. At his best, and as a feasible hedge against such shortcomings, he creates a visual non-reality built of silhouettes, abstract shadows and mechanically precise lines. By 1950, Gould and his assistants had synthesized a signature look-and-feel. The strip is remarkably consistent through this decade, and stays the course until 1965 or so.

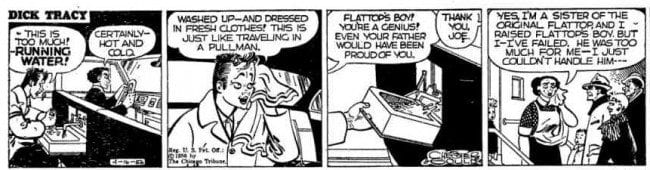

Back to our '56 recap: Joe Period climbs into a well-like railway container (Gould's favorite type of nightmare-trap: claustrophobia rules his world). He finds it's filled with pickles and freezing brine. He is rescued by—wait for it—the son of Flat-Top. The spitting image of his old man, who lives with a look-alike aunt (the Flat-Top genes are sturdy), Jr. is an electronics genius and something of an artist.

Period is bowled over by Flat-Top Jr. At least 10 times, over a few months, he exclaims, “Boy! You're a genius!” or words to that effect. Though FT has no apparent criminal record, he immediately chooses to join Period's path to perdition.

The teens team up and live out of FT's customized car, loaded with Space Age amenities (working sink, stove, fridge, TV, hi-fi and radio) as they evade the police in a prolonged escape. Their goal is to double back to the city, where Joe will slaughter nightclub owner “Nothing” Yonson, the noodle-faced slickie who tossed him on the train.

They succeed; Yonson lives long enough to finger Joe, while Flat-Top Jr. escapes in his car of tomorrow, rents a room in a boarding house and poses as a young art school student. The landlady's nosy teenage daughter, Skinny, develops a crush on the brooding, distant teen. This would-be romance ends as FT hurls Skinny off a rooftop to her death.

In the aftermath of this crime, Flat-Top Jr.'s cool demeanor—and sanity—are permanently shaken. He feels the spectral presence of Skinny, her arms around his neck, hanging onto his shoulders, her face adoring and smiling, and panics.

Gould's stories are often most fascinating in their small details—little tells that suggest more than is said on the surface. Gould loves the set-up of a new story: one can sense him wringing his hands with glee when he upends his scenery and cast. Cause, effect and inevitability weigh heavily in his narratives. He is driven to show how an individual becomes a criminal, and then how that criminal is driven out of society and into a limbo of pursuit and escape, with imprisonment or death waiting at its end.

Gould draws the image of Skinny's ghost, enmeshed with Flat-Top Jr.'s corporeal form, over and over during the summer, 1956 strips. On the surface, this was business-as-usual. Gould was fond of doubles and repetition throughout the run of Dick Tracy. The obese, Elvis-coiffed Clipso Brothers, who appear in a 1957 sequence, look, think and gesture as one. The naive, doomed Summer Sisters, from a 1944 storyline, are another of Gould's comics simulacra. He is also fond of drawing images of an event again and again, from the same POV.

Tracy's summer 1956 strips have no comparable moment in Gould's career, and are left open to interpretation. Gould obliquely hints that FT's guilty conscience has cooked up this hallucination—but it really seems that he has lost his mind. On 9/25/56, Flat-Top Jr. disappears. Things calm down. Tracy and Sam get crew-cuts. A new narrative gets rolling.

There is no mention of Flat-Top Jr. and his madness—it's as if it never happened. We meet Specs, a sunglasses-wearing, mute little girl, Ivy, a Jerry Lewis look-a-like who lives in an underground counterfeiting lair (and obsessively sings the Yale fight song under his breath) and Rodney, a dim-witted engraver kept permanently shackled to Ivy's subterranean workspace.

Madness, depicted on the comics page with sobering fervor.

On November 23rd, Flat-Top Jr., now emaciated, his Frida Kahlo haircut snow-white with stress and madness, is spotted running through a barren rural landscape. He is killed by police-woman Lizz, a former nightclub employee of “Nothing” Yonson's who signed up for the force on New Year's Day, 1956. As life leaves Flat-Top Jr.'s body, the ghost of Skinny finally releases her grip, salutes Lizz and vanishes.

Oh—and Ivy gets one of his arms chewed off by a shark, and his counterfeiting lair is blown up by Rodney, who has his first Christmas as a free man since 1925.

The most striking moments of '56 are those serial images of the deranged Flat-Top Jr. running to escape the clingy phantom of Skinny, who holds the same position, looking off to her right, smiling, as if she's enjoying a carnival ride. They are the acme of Gould's cracked poetry. Their potency is strengthened by their availability in collected form. To see that same damned moment, over and over, is mesmerizing in a way that I don't think Chester Gould could have anticipated.

Gould's serial images of the fleeing Flat-Top Jr., hugged by a teenage ghost.

As is evident from this year's work, Dick Tracy has a strong hint of outsider art—of deeply nursed, highly personal convictions that make perfect sense to their creator, but remain inscrutable to the rest of the world. The average Tracy story-line will have its share of “huh?” moments to modern readers. (For example: the repeated moment, in the mid-1950s, of characters holding up a hand, in a sort of salute, and saying “Peas.”)

But Tracy was “insider art” with a vengeance—created and promoted within the system and eagerly absorbed by millions of readers. Gould's work cuddled up inside the American psyche of the 1930s, '40s and '50s. These were violent, uncertain times, and the threat of gangsterism—Tracy's impetus in 1931—gave way to our national fear of Fascism, Nazism, communism and nuclear war. Dick Tracy both celebrated and mollified those shared terrors.

Gould's angular, flat artwork of the mid-1950s held obvious appeal to the Pop Art generation, who celebrated the ready-made crassness of American detritus, without digging too deep into what made it tick. Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein approached the subjects of their appropriations as pivot points for quick irony. Jess Collins' Tricky Cad pieces are sourced from Gould's Eisenhower-era work.

It would be convenient to dismiss Dick Tracy as crass pop detritus, the ready-made, callous stuff that aggressively filled (and fills) every corner of American life. Lesser by-products, such as a 1960s limited-animation TV cartoon series and Warren Beatty's over-stylized 1990 Hollywood film, might lend credence to the assumption that Tracy, like most other “old stuff” (i.e., popular culture before Star Wars) is quaint junk, interesting for a few moments' diversion, but not significant.

Free of this guilt-by-association, Gould's work retains its loud, loopy grumpy, self-satisfied, sometimes impatient voice. The son of a Pawnee, Oklahoma newspaperman, Gould considered himself a sort of journalist, in that his work had some relevance to front-page headlines. Gould’s work was a vital component of the daily newspaper, and a strong selling point for readers. Tracy's hold on front-page realism was tenuous, at best, after 1933, but truthful elements were part of its eccentric fabric.

Gould consulted police departments and read up on new developments in criminology. Amidst its daffiest narratives, the no-nonsense crime laboratory is a place of reason and logic in Gould's world. Forensic science is a part of Tracy's daily life. Between narratives, the reader is likely to find a couple of days on police judo techniques, updates in radar technology, a brief treatise on police dogs, etc. There are also bouts of sermonizing on the good police do for their community, and in hoping that young people will be law-abiding, and consider police work as a career option.

This do-good messaging created enough of a sense of public service that Chester Gould was free to follow his whims wherever they led him as a comics storyteller. This, in turn, shielded him from potential criticism in an era when comic books were under great scrutiny and societal condemnation.

Through the run of Tracy, and especially from 1944-1963, Gould got away with murder—a serial barrage of the most brutal, nightmarish images in the history of American comics and crime literature.

EC's horror comics have nothing on Dick Tracy—and Gould's work wore the cloak of respectability. In the 1950s, as comic books were purged of their freedom and the target of investigations, Gould's nightmares came wrapped around America's Sunday papers, as the lead feature of most color comics sections. The daily strip was typically displayed at, or near, the top of subscribing papers' comics pages. It was an institution by the dawn of the 1950s, and enjoyed a curious immunity as the battle against comics raged around it.

Gould is among the great crime fiction writers of the 20th century. In his 1980 interview, he brags, with some justification: “I was ahead of Dashiell Hammett....[I] was trying to out-do every cartoonist in the business. My theory was 'Stifle All Competition.'” (“Chester Gould Speaks, Part II,” Max Allan Collins and Matt Masterson, from The Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy Vol. 2: 1933-1935, conflation of two quotes from p.7) Gould often resorts to soap-opera to keep his readers' attention. For Tracy's pop reputation as a shoot-'em-up action-fest, there is a large amount of non-violent melodrama in its mix. Again, this hedged Gould's main obsession as a pictorial storyteller—the graphic depiction of violence.

A fondness for out-of-nowhere humor and farcical supporting figures chaperons this dread and doom. The argument can be made for Dick Tracy as a screwball comic strip with elements of the police procedural. Gould's villains are typically absolutes or caricatures, designed with a comic artist's eye, and not cast from reality. Reducto ad absurdum supporting figures such as Vitamin Flintheart, B.O. Plenty, Gravel Gertie, Vera Alldid and Peanut Butter Bailey are accepted colleagues of Tracy, Sam Catchem and Chief Patton—nuisances who obstruct progress by their very existence.

Gould's attempts at humor are as unnerving as his bouts of graphic violence. Like Jack Webb's stabs at levity in his Dragnet TV series and his 1950s feature films (The D.I., --30--), Gould's humor seldom comforts or convinces. It sits there, demanding that you acknowledge its awkwardness. 1956 is a relatively humorless year for Dick Tracy, which may be why it's my favorite stretch of his work. Though my description of the year's events sound zany, they are presented with drama, pathos and tension—all shot through with their creator's eccentric eye.

Tracy's biggest pull is Gould's savant skill as a storyteller. Gould knows how to suck the reader into his world. He runs the same doomy cycle time and again, from the strip's 1931 start to his sign-off in 1977. A criminal creates a crescendo of (usually homicidal) anti-social acts, flees the pursuit of the police, and becomes hoisted on a (usually symbolic) petard, his mangled corpse in public view on the newspaper page. Like the prose mystery writer Fredric Brown, Gould is fascinated by the pursuit. The crime and punishment steps interest both men less than the middle of this story formula: the wrongdoer (alleged or convicted) on the run, disconnected from society and trying to survive their broken life. With this double-edged pursuit as their core, Gould's narratives, like those of Harold Gray's Little Orphan Annie, are intensely, nervously absorbing. Gould outdid Gray in his ability to layer story-lines. At his best, Gould can keep year-old narrative threads alive, while pursuing two or three newer veins.

Like Harold Gray's work, Chester Gould's has been restored to currency, via an ongoing series of lavish hardcover books published by The Library of American Comics, an imprint of IDW overseen by Dean Mullaney. As of this writing, the LoAC has reprinted the entirety of Dick Tracy through mid-February, 1961.

Tracy has its obvious peaks and valleys, as the LoAC books confirm. Sequences from 1932 through 1936 show Gould in his first flower as a storyteller. Everything is there—the dread, the silhouettes, the dark shadows and death. By 1938, the strip veers into pulp/radio-style melodrama and doesn't regain its footing until 1941, with the first of Gould's infamous series of caricature-villains, Littleface.

Gould is red-hot during World War II, with narratives involving Prune-face, Mrs. Prune-face, B. B. Eyes, 88 Keyes, Laffy and his most-remembered wrongdoer, Flat-Top. The Flat-Top sequence, which ran from the tail end of 1943 to May, 1944, is Gould's first masterpiece—the perfection of a story he had told before, in dozens of different ways, but never with the same sense of oppressive, smothering predestination. Tracy falters in the post-war 1940s, with the exception of a late-1947 narrative featuring the enigmatic Mumbles—one of the few Gould caricature-villains brought back to the strip (most died after one crime spree). The Mumbles sequence suffers, as do many Tracy narratives of 1946-1949, from being too compressed and rushed.

The down-home antics of B. O. Plenty, introduced in 1945, and his family, come to dominate the post-war strip, as does Junior Tracy's goody-two-shoes crime fighting club. Gould may have needed a karmic rest, after the dark march of the war years, but his obsession with the Plenty clan proves trying, and the strip limps.

The introduction of Jewish cop Sam Catchem, as Tracy's cohort, in 1949, signals Gould's return to top form. Catchem was Gould's first truly ethnic protagonist. In the wake of the monstrous, lumpen black characters in the '30s Tracy—among the worst offenders in the annals of pop stereotyping—it is surprising that he feels such fondness for Catchem. Sam's Jewishness is only obliquely referenced, but he is clearly not cut from the same hardy mittel-America cloth as Tracy and Chief Patton. Catchem, in effect, saves Dick Tracy from strangling on mediocrity.

1951-1962 are Gould's golden years: intense, anguished, doom-laden shadow-and-silhouette nightmare stories, in which isolated happy moments have dark, damaging payoffs, and Tracy is battered, burned, starved, tortured and left for dead.

In the 1980 interview, Gould confessed that he often put Tracy into crises so absolute that its creator had no idea how to extricate him. “[T]hat would ruin the whole thing, if I tried to figure it out,” Gould said. “Because you would say, 'well, I wouldn't do that—it's too hard.'” (“Chester Gould Speaks, Part II,” Max Allan Collins and Matt Masterson, from The Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy Vol. 2: 1933-1935, p. 9)

Gould, in this period, was rivaled in mass culture only by the film-maker Sam Fuller, whose hyperbolic, excitably-named movies (Pickup On South Street, Verboten!, Underworld U.S.A.) similarly struck the public's fancy. Fuller, whose movies fell from mass favor by 1964, could have made a great Dick Tracy picture, circa 1955.

Gould and Fuller share a passionate belief that any story they tell, no matter how ludicrous in theory, is valid, and deserves our full attention. Without this self-confidence, neither creator's work could hold up.

A perfect example of this from Fuller is a sequence from a 1949 film noir he scripted, and Douglas Sirk directed. Shockproof, a non-sequitur attention-grabber of a title, stars Cornel Wilde as Griff Marat, a probation officer assigned to keep close tabs on a female ex-con Jenny Marsh (Patricia Knight). Her former flame Henry Wesson—a condescending professional gambler (played like a Gould caricature-villain by John Baragrey)—keeps tugging Jenny back into the world of crime.

One screwy event after another tumbles down Shockproof's narrative line; Griff and Jenny fall in love, and after Jenny shoots Wesson dead (so she thinks), she and Griff become fugitives from justice. In the excerpt I've sawed off from the film, Fuller and Sirk achieve a remarkable simulacra of Gould's wrongdoers-in-flight motif, with the fear of capture pushing them deeper and tighter into a living hell. In Shockproof's case, it's a colony of skeletal shacks that offer the fleeing fugitives zero privacy, as they dodge and duck their fate until no course of escape exists.

Here's the link:

https://youtube.com/dK5PVROHBFk

Though the '50s saw a resurgence of the adventure continuity in newspapers, little to none of that work retains any relevance now. Besides Gould, Roy Crane, Milton Caniff, V. T. Hamlin and Leslie Turner still held to their high standards of narrative and artwork. But their daily canvas diminished and self-destructed.

As newspaper space for comics shrank—especially true for the daily strips—these artists had to make do with less and less. Gould's artwork becomes more diagrammatic after 1965. By that decade's end, it's nothing but thick outlines and stark black and white. The crazy ideas still occur, as do the weird shadows and silhouettes, but the artist and his assistants had forever lost the room to make Tracy as they had in the late 1940s and through the '50s.

By 1972, it was clear that Gould had said all he could ever say with Dick Tracy. If the book reprints reach this period, it will be interesting to reassess Gould's late work. There are glimpses of that jovial, self-determined American crazy, right up to the last strip he drew, published on Christmas, 1977. Until then, let Gould's work be read and celebrated as delirious, loopy, occult Americana—it offers entry into an inscrutable mind and the world that fostered its greatest work.