The following selection is from my book, "How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?": Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs, which looks at the works of seven women cartoonists. Each artist explores her Jewish identity through comics, and some more explicitly than others. This excerpt is taken from a chapter focused on Vanessa Davis's two autobiographical collections, Spaniel Rage and Make Me a Woman. Here I examine the ways that Davis's first book relies on and plays with certain conventions of the diary genre. While Jewish identity is not overtly explored in this early work, I argue that Davis's manipulation of the diary form here allows her to practice certain engagements with personal storytelling that are developed more fully in her later work, particularly in relation to her Jewish identity.

The following selection is from my book, "How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?": Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs, which looks at the works of seven women cartoonists. Each artist explores her Jewish identity through comics, and some more explicitly than others. This excerpt is taken from a chapter focused on Vanessa Davis's two autobiographical collections, Spaniel Rage and Make Me a Woman. Here I examine the ways that Davis's first book relies on and plays with certain conventions of the diary genre. While Jewish identity is not overtly explored in this early work, I argue that Davis's manipulation of the diary form here allows her to practice certain engagements with personal storytelling that are developed more fully in her later work, particularly in relation to her Jewish identity.

Note: Spaniel Rage was initially published by Buenaventura Press in 2005. It will be republished by Drawn & Quarterly in early 2017.

“But that is Only A Small Part of Why I Feel Like Total Shit”

Published in 2005 by the now defunct Buenaventura Press, Spaniel Rage is a collection of what Davis describes, on one of its title pages, as “diary comics and drawings that I made in sketchbooks from 2003 to 2004.” Assembled in a thin, soft-cover book about 10 inches tall and 7 1/2 inches wide, the text can most accurately be categorized as a graphic diary or journal. In this chapter, like autobiography theorist Philippe Lejeune and others, I do not distinguish between the diary and the journal. Some critics make a debatable distinction by correlating journal writing with an intended public audience and content that is less so-called personal. This distinction sets up a hierarchical dynamic—with the diary often cited as a “feminine” and the journal as a “masculine” form—between two modes of writing that have, despite their differing histories and genealogies, become otherwise indistinguishable. Davis’s collection does not include pagination, and one or more often but not always dated entries fill each page. As Lejeune explains in his essay on diaries, “On Today’s Date,” page dating is one of the characteristics that helps define the modern day diary and distinguishes it from other literary and nonliterary forms, including autobiography. The date scrawled or typed at the top of the page reflects “people’s relationship with lived time” (80); specifically, it demonstrates a particular awareness of the continual passing of and subsequent accounting for time. It also stands as a “pact of truth” (79) in that it “certifies the time of enunciation.” By tracking time on the page (or, for some, on the computer screen), the diarist testifies to what is beyond her control, while she also acknowledges her powerlessness over the situation, the inevitability of death and, consequently, of the diary project. That Davis dates some but not all her diary entries is significant, most importantly because it hints at her work’s ability to complicate stylistic conventions in order to create new composite forms of self-representation that defy normative expectations. As she explained in an interview, “I think that it’s important for people to try to be realistic and not strive to fit some template of what works or what sells or what’s popular or what’s considered legitimate. I think people should just do what works for them and see where that takes them” (“Interview: Vanessa Davis”). The structure of Davis’s journal as a whole also reflects this independent style. For instance, three-quarters of the way through Spaniel Rage, a book that otherwise includes no chapter or section divisions, she includes various short comics labeled “Other Stories” and marked as each having been published previously in other locations. The title of these comics, in stressing “otherness,” points to the difficulty of categorizing the various types of texts included in the book and therefore establishes what will become, in both of Davis’s works, a more general preoccupation with categorization and typology. The inclusion of these longer-form comics—each divided from the other by a single blank page—at the end of what is primarily a graphic diary also complicates the possibility that her works, in publication, will fit a particular, clearly defined genre or market standard. By incorporating images created for publication alongside images presumably drawn for her eyes only in what started as a sketchbook, Spaniel Rage thwarts the simple distinction often constructed between the two forms of creation. In this way her text questions the notion that authorial intention or imagined audience is ever clear-cut or formulaic. A resistance to such conformity is also pronounced in her later work, Make Me a Woman, which, also like Kominsky Crumb’s memoir, represents a dramatic departure from a categorizable literary product with an intended audience.

The structure of Spaniel Rage additionally draws attention to the published diary as a work that has inevitably been exposed to edits, and that has been transformed in the process of its publication. Lejeune and others have written extensively on the near impossibility of reading diaries, especially contemporary ones, in the form that they were originally composed, prepublication. Consider, for example, the fact that printed versions of diaries often do not reveal the various nuances of the original text, from handwriting (and changes in handwriting) to the spaces left between words (Culley, “Introduction” 16). The title page of Spaniel Rage is drawn in the handwriting of the artist, with watercolors filling in carefully bubbled, black-and-white cursive letters. Thus the title as well as the name of the press and city of publication are adapted in the pages of the graphic diary and reestablished as part of the diary composition itself. Davis’s work therefore blurs the distinction between “paratext” and main text, and preempts the possibility of ever fully differentiating between the two. As Gérard Genette explains in his seminal book on the topic, the paratext, a term encompassing elements like the author’s name, the title, or the introduction to a work, “surround . . . and extend” the text “to ensure the text’s presence in the world, its ‘reception’ and consumption in the form (nowadays, at least) of a book” (1). In the case of Davis’s work, the intimacy of the hand-drawn paratext prompts readers to approach the book as a unified project that does not distinguish between its creation by a single author and its publication history. The overall structure of the book therefore resembles the way that the self gets established in its pages, as an entity that cannot fully be understood by looking at isolated experiences, memories, or reflections but rather needs to be considered in the context of the work as a whole, including factors that take place outside of, or alongside, the author’s immediate creative control. The hazy boundary between text and paratext additionally destabilizes a notion of self as insider or as one who belongs, even in an iteration of one’s own life story. Just as the paratext is marked by the hand of the author, the journal entries themselves, creations emerging from and reflecting the inner life of the artist, are equally and easily subject to the taint of outside influences, including those of the publisher and of anticipated and actual readers.

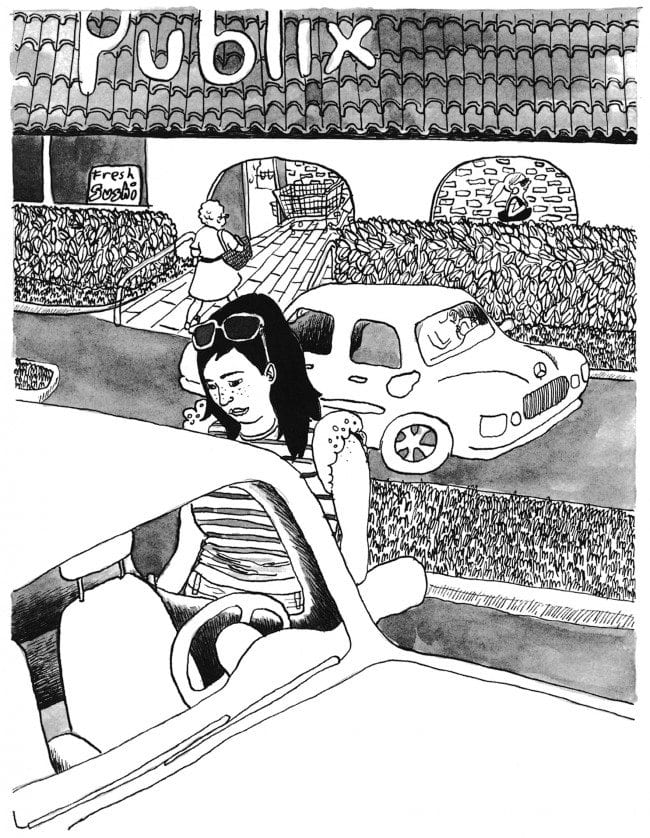

The question of audience and influence is especially important in a genre often mistakenly presumed to be written for the self alone. Margo Culley writes in her introduction to A Day at a Time, “The importance of the audience, real or implied, conscious or unconscious, of what is usually thought of as a private genre cannot be overstated. The presence of a sense of audience, in this form of writing as in all others, has a crucial influence over what is said and how it is said” (11–12). The framing of Davis’s text draws attention to the question of audience from the outset of the book. The image adjacent to the title page, for example, proposes Davis’s graphic diary as a work that does not simply fall into any preconceived notion of a public or private document (in intention or execution), but rather wavers somewhere between both spheres. Beside the handwritten, and in this way individualized, title page, there is a full-page black-and-white drawing, which is the first image we see of Vanessa (figure 2.1). She is pictured standing in front of her car in a supermarket parking lot. There is no verbal etching attached to the image but for the word Publix scrawled across a terra cotta roof and a Fresh Sushi sign leaning against the supermarket wall. Publix is an employee-owned supermarket chain, with most of its stores located in Florida, which is where Davis grew up and her mother now lives. The lack of context or narrative connected to this drawing prefigures the style and tone of the rest of the graphic diary, which does not focus on a directed accretion of experiences and reflections in order to form a narrativistic whole, but rather documents a paratactic and fragmented panorama of self, recorded in narrative and nonnarrative spurts over a single year. Vanessa stands looking down at the door of her car, ostensibly fitting her key into it, although this action is obscured by the vehicle (we see her arms but not her hands). The image presents her moment of passing or moving from a public space into a semiprivate one, an act that, in itself, is partially hidden and partially visible, cropped and directed from a corner angle overlooking the scene. Like this self-representation, the composer of the journal is similarly situated in a transitional framework. Whether or not she ever intends to show her diary to others, she is always at risk of having her work exposed merely by putting down words or images on a page. In this sense, she is always affected by, and maintains an awareness of, the possibility of an audience larger than herself. Her seemingly private universe, in being transcribed onto the page, is always part of a larger public landscape. As Lynn Z. Bloom argues, “it is a mistake to think of diaries as a genre composed primarily of ‘private writings,’ even if they are—as in many women’s diaries—a personal record of private thoughts and activities, rather than public events” (24). Diaries written with no intention of publication always involve some kind of awareness of a possible public audience since “the writing act itself implies an audience” (Culley, “Introduction” 8). Conversely, even if the author intended the work to be published from the outset, there are always private meanings hidden in the diary to which certain audiences will never have access.

Vanessa, as pictured at the opening of the diary, is documented at the cusp of both of these worlds, the private and public, reflecting the status not just of the writer of the diary but also the reader-viewer, who is about to enter someone else’s semiprivate world through the space of a semiprivate document. But this visualization of the diary writer’s stance, the image of Vanessa standing at the threshold, is further complicated by its transmission as an image, and a large, full-page image at that. From its outset, this diary is presented primarily as a visual document, framed not in and through the word but, instead, in and through structures of looking. As W. J. T. Mitchell, among others, has shown, images are presumed to invite viewers as spectators, as passive surveyors. The mere presence of an oversized visual depiction of the author at the opening of this diary thus also implicitly undermines the notion of the diary as a private text, as one not meant to be seen by others. Yet, even as the overwhelming presence of an almost wordless image at the beginning of the diary invites that problematic connection between the visible and public, between images and exposure, the angled, partially concealed content of the drawing nevertheless reinforces the disestablishment of such simple binaries. The scene is highly specific, a fragment of a fragment of a particular perspective. Further, the facing page is the aforementioned title page, which consists only of words, even if they are intimately, hand-drawn ones. It reveals nothing “personal,” relaying only the title of the book, its author, its publisher, and its publisher’s location. More broadly, then, when put in context, the opening of Davis’s book subverts the expectations audiences often assign to their readings of different kinds of texts, particularly the diary. In many ways this destabilization of genre conventions—the breaking down of reader expectations—is mobilized through the spatial and visual structures available uniquely through the graphic narrative form. By placing a full-paged image facing a hand-drawn, word-based title page, the reader is compelled to establish connections and comparisons. In this case these include the differences and similarities between texts that communicate primarily through images and those that communicate primarily through words or texts that presumably profess exposure and “truth” and those that potentially undermine such claims. By depicting various registers relationally, across several or numerous pages, Spaniel Rage reflects the means by which comics more generally can activate productive confrontations with categories like genres or mediums that are so often taken for granted.

The content of the diary beyond the title page and opening image also plays with the assumptions that frame expectations about audience and intention, particularly as they relate to narrative and nonnarrative representations of self as well as the constructed distinctions that are often made between public and private spaces and acts. A number of the journal sketches figure Vanessa in her apartment and, often, even more privately, in her bed—a repeated setting in both of Davis’s books. Other recurring scenes illustrated throughout include Vanessa at work, on the telephone, at a restaurant with a single companion or various friends and family, in bars with friends or on dates, at concerts, and commuting on a subway train. Many of these scenes are left either unnarrated or involve narration that consists only of dialogue without any overarching narrative voice to interpret or connect the various settings and spaces. These repeated representations emphasize the diary as a space in which the seemingly inconsequential gets recorded, where daily public and private experiences that might otherwise be forgotten— either because they are so often repeated and familiar or because, in memory, they fade easily into more significant events—are documented. But a closer look at such scenes also reveals the potential for connection and relevance, for construction and engagement within the presentation of such seemingly trivial or disconnected recordings.

In one early sketch, dated May 12, 2003, for example, Vanessa sits in front of her computer at her work desk (figure 2.2). The same event is depicted in three adjoining panels, drawn in heavy and light pencil lines with next to no gutter space separating them. The changes between the three carefully drawn images can be seen in the details: Vanessa’s arm moves from the mouse to the keyboard and back to the mouse again. Her chair swivels slightly. Her head tilts to the right, as she moves closer to a subtly changed screen, and then back again. A shelf in the background almost disappears by the final panel, as the perspective is slightly modified. In itself, the black-and-white entry featuring Vanessa at work presents a seemingly trivial slice of life. The cinematic quality of the diary entry, which looks like part of a filmstrip, imbues the images with the sense of time passing, but their static nature slows that time down and signifies the sense of monotony that comes from working long hours at a desk job. Nevertheless, the slight variations between the three images also ingrains these moments with a certain significance, recalling the keen eye, and careful hand, of the observing artist. The diary becomes a space not just for recording but also for studying and even sharpening acts and moments that might otherwise remain cloudy and inconsequential. The act of chronicling transforms the events and scenes being portrayed.

In addition to the sense of attentiveness and constructedness that permeates individual entries, when an entry is amassed as part of a larger collective, when it is read in relation to another entry or in relation to many entries, it acquires other new meanings. This particular office scene is depicted on the same page as a much more intimate, smaller, and single-paneled entry, dated May 11, 2003. A woman’s breast, lightly shadowed and in profile, is the focal point of this loosely drawn rectangular panel, and a sketched face with pursed lips and clearly delineated long eyelashes looms over the pointed nipple. In the background a series of diagonal lines calls attention to the corner of a window frame, with several small branches recalling another world outside this very intimate space. Taken together, in such close proximity, this page of the diary evokes the complex and often paradoxical web of intimacy, familiarity, and distance that an individual experiences over short time frames. A secret, sexual act can be observed, in the diary as in the mind of a participant, from a cool remove, or it can be juxtaposed with scenes that feel otherwise incompatible but nevertheless potentially connect to those previous private moments. The images of Vanessa at her office desk, clicking away at e-mail messages that cannot be deciphered by the reader, similarly demonstrate how trivial experiences that occur in public places can potentially relate to more intimate moments.

These engagements additionally complicate the notion of the diary as a space reserved solely for the reflection or refraction of one’s intimate or “personal” thoughts and experiences. As many critics have pointed out, while the diary can focus on an exploration of a person’s “inward journey,” meaning her interior thoughts and emotions, “the reader must remember that the idea of the diary as the arena of the secret, inner life is a relatively modern idea and describes only one kind of diary” (Culley, “Preface” xiii). In other words, to presume diary making to be an act of confession and self-contemplation, one that focuses exclusively on an individual’s secret or private experiences and reflections, is an assumption that ignores not only many of the historical precursors to the modern day diary but also overlooks the many different functions of the diary that exist even today.

Another characteristic of Davis’s diary, for instance, is its frequent attentiveness to the process of its very construction. The entries are often spaces where the author can work out aesthetic issues and create or develop a method of cartooning. Indeed, various aspects of many of the illustrations throughout point to the diary’s use as, among other things, a workbook, in the sense of a book where work-related problems can be recorded and explored, or simply a place where writing and drawing habits are noted. In her introduction to Drawn In, a collection of sketchbook excerpts from various artists (with a preface by Vanessa Davis), illustrator and sketchbook creator Julia Rothman describes sketchbooks as serving this function, among others. As she explains: “Within sketchbook pages, one can trace the development of an artist’s process, style, and personality. Sketches emit a freshness and vitality because they are the first thoughts and are often not reworked. Raw ideas and small sketches are the seeds for bigger projects. Sketchbooks ultimately become the records of artists’ lives. They are documented visual diaries” (12). Within its pages, Davis’s journal, which, as mentioned, was culled from her sketchbooks, includes images and diary entries that reflect such a progression of her “process” and “style.” For instance, on a sketch dated May 24, 2003, the author draws a starred footnote in the corner of an image that says, “Not even close resemblances to Rebecca and John.” Several of the images include self-criticisms related to her work habits, like the introduction to an entry dated July 2, 2003: “I haven’t drawn in more than a week. But that is only a small part of why I feel like total shit.” This particular notation reveals how self-reflections in terms of work-related habits often overlap to combine with other, less specific considerations, such as a general ontological anxiety. Both the structure and content of Davis’s graphic diary thereby redefine the scope and practice of journaling as a space of relative freedom from conventional genre standards, expectations, and norms where diverse practices collide and interact to reflect a self in the making.

By juxtaposing various kinds of explorations and observations within the same text, often even on the same page or within the same image—those taking place in public spaces and those taking place in private ones, those formulated in a social setting and those framed in relative isolation, those focused on aesthetic issues and those testifying to daily experiences and modalities—Davis’s journal presents self-chronicling as a process that, despite its fragmentary nature, inevitably unifies to form a kind of assembly on the page. As Culley explains, “Keeping a life record can be an attempt to preserve continuity seemingly broken or lost” (“Introduction” 8). Indeed, by bringing together the various aspects of our lives that are normally thought of as disconnected, like significant life events alongside mundane everyday realities, or publicly located experiences and private ones, the diary, graphic or otherwise, can help create a sense of cohesion between various senses of self over time. In their introduction to Inscribing the Daily, Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia A. Huff argue that the unique forms of diaries, unlike autobiographies or other forms of personal writing, “challenge us to question the boundaries between the public and the private; and they encourage us to assess the social, political, and personal repercussions of segmenting our lives, our texts, our culture, and our academic disciplines” (2). Davis’s diary entries reflect the ways that mapping together various forms of experience, through the many places and perspectives that inflect and inform those experiences, can actually lead to a stronger sense of a unitary self. In her graphic diary the multifarious geographies that make up the individual’s worldview are all leveled and consequently equalized on the surface of the page to be considered in relation to one another.

One way of better understanding how this unification through fragmentation occurs is by recognizing the integral difference between the practice of autobiographical and diary writing. As Lejeune writes in his essay, “The Diary as ‘Antifiction,’” “the problem of autobiography is the beginning, the gaping hole of the origin, whereas for the diary it is the ending, the gaping hole of death” (201–2). Since the diarist never knows what will happen next, life is presented as a series of unfolding events without any “retrospective point of view” (Cates 213). For this reason, as various critics of diary writing have pointed out, fictional diaries often sound overly contrived and constructed. It is this sense of an unknown future that is so difficult to replicate in the fictional realm. Generally, there is no way of knowing what past events will gain in significance over time or become irrelevant, so in a nonfictional journal all events, experiences, and reflections stand within a certain range of equality on the page. In this way diaries, unlike autobiographies, represent a relatively unsentimentalized or unfiltered view of everyday life, as much as that is possible. This unfolding more closely resembles life as it is actually experienced, with the act of representing one’s self and the places one inhabits as something always entrenched in the present, with no clear or definite sense of what the future holds or how the past will link to that future. This structural difference between diaries and other forms of personal writing and composing ensures that even the most public nonfictional diary—a diary, for example, created with the intention of publication—always maintains some pretense of itself as a private document. The underlying narrative structure of the diary can never be fully decoded since the future arc of the story always remains a mystery to the writer herself. Even, or perhaps especially, for its writer, though also for its audience, the diary is a somewhat contained and mysterious text.

As a mode of life writing that always involves some mysterious elements and hinges on an unknown future, the graphic diary therefore differs dramatically from the recently popularized “graphic novel memoir,” like Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home or Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, in which the story line frequently pivots around an often traumatic event or series of events from the past. As Isaac Cates explains, “A memoir, in comics or in prose, requires a degree of structure, a degree of deliberate storytelling, that is not available to diary comics, because the diarist can never entirely see the larger plots and arguments that his life will eventually fulfill” (214). By presenting life as a set of vignettes without any obvious links between individual images, the graphic journal more clearly reflects the absolute integration of past experiences and settings of all kinds into an animated present, especially because there is rarely a definite sense of how one location or experience will relate to another over time. It is in part for this reason that Davis’s diary showcases a self reflective of Eakin’s “totality of [a] subjective experience,” rather than, as in Make Me a Woman, a self composed of predetermined public identities. The added autobiographical narrative element incorporated into Davis’s second book allows for a more focused self-analysis. It could be said, then, that in Spaniel Rage Davis introduces many of the themes she later and more directly explores in Make Me a Woman. The graphic diary allows her the freedom to pose questions without necessarily answering them. It serves as a kind of dress rehearsal for a more fully developed and manifestly public exploration of what eventually reveals itself, for the author, to be a most urgent and vital set of questions about self-representation and self-knowledge, and which is evoked most explicitly in relation to representations of Jewish identity.

Excerpted from "HOW COME BOYS GET TO KEEP THEIR NOSES?" by Tahneer Oksman. Copyright (c) 2016 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.