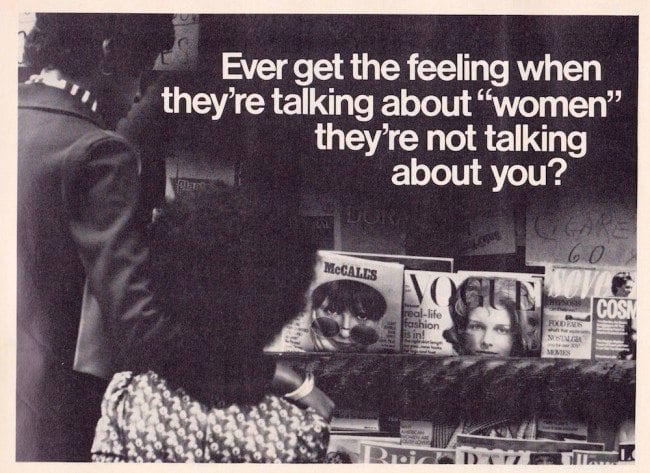

While doing research for an exhibition I co-organized, Our Comics, Ourselves, I came across the first newsstand issue of Ms. Magazine from 1972, the cover depicting a modern Wonder Woman as the embodiment of the new, liberated female. Perfect, I thought. Here’s a solid connection between comics and feminism, two things I care immensely about and that I want to put on display. I thumbed through articles by Gloria Steinem, Germaine Greer, and Erica Jong, and then halted at an ad for Ebony Magazine that asked, “Ever get the feeling when they’re talking about 'women' they’re not talking about you?”

Yes. All the time. And for as long as I remember. (Although this particular ad was specifically targeted toward Black women, the larger point holds true—what is often presented as “women’s experience” excludes large swaths of women.)

My true feelings were outed. Even though I love comics and my politics are feminist, the reality is that I have always had trouble seeing my own experience reflected in “feminist comics.” Admittedly, I’ve bought, read, and written about feminist comics in the direct hope of discovering other versions of myself, experiences that I could relate to, and narratives that might embrace me in a type of membership. In other words, I don’t identify with Wonder Woman and other graphic narratives that explicitly represent women in name or idea, and it makes me wonder, is there something wrong with me, or something wrong with these comics?

I find the feminist underground comix from the 1970s so appealing—the irreverence of the writing and variations in drawing styles are so rich—but they were rooted in events that seem so remote at this point. Many were focused on a woman’s right to her own body—the right to seek and enjoy sexual pleasure without social ostracizing (The Bunch's Power Pak Comics), the right to obtain a safe and legal abortion (Abortion Eve), and the right to work any job a man could, to live alone, and to fart whenever necessary (The Compleat Fart). These just aren’t my struggles—and thank goodness for that, especially the last one. I was born into a world where women had already fought a solid first round for all of this. (However, it’s clear that another round is now due for abortion access. More on that below.) But, as much as I love the confident draftsmanship and balls-to-the-wall humor of Lee Marrs, the pained confessional stylings of Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and the “giving zero fucks” attitude in everything Joyce Farmer ever did, I can’t say that I relate.

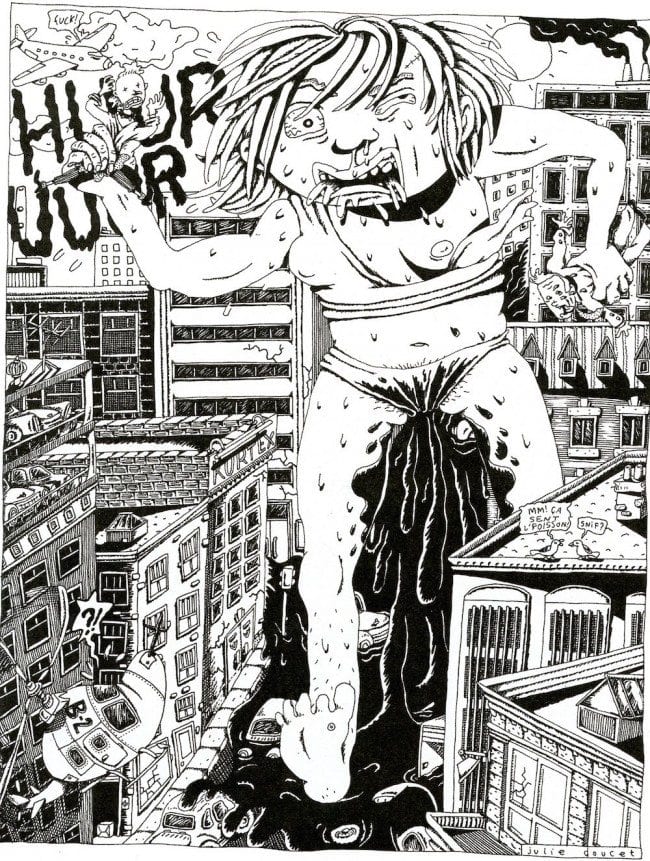

The '90s should be my generation of comics, but the times were so heavy with identity politics that, even as an angsty, artsy teenager, I found it all to be off-putting. The comics were either too dark, too gruesome, or too didactic. I’m thinking of Julie Doucet’s Dirty Plotte, Diane DiMassa’s Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist, or even the short-lived Girltalk. In my recollection, there were too many images of gushing menstrual cycles, too many lessons in vagina anatomy and articulations of sexual abuse, and too many acts of violence—only thinly cloaked in humor—against douche-y men. These comics delivered direct and grating statements about gender politics and injustice. At fifteen, I was unprepared for that kind of intensity. In hindsight, I just wasn’t ready to be politically engaged and that’s precisely what those comics demanded its readers to be. Instead, I wanted to laugh loudly at the funny parts of Janeane Garofalo’s stand-up routine, dance confidently to TLC, and wear enormously baggy jeans at the mall, without having to process that in my own way, these were all statements about feminism, self-protection, and reclaiming the female voice.

Diane DiMassa, Hothead Paisan, Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist n. 16 (Giant Ass Publishing, 1991).

Now, just seconds from turning forty, I’m both politicized and angry, and I long for the intensity of those '90s comics. And I look around at comics written by and about women and they seem so understated. There is still so much to be upset about—Bill Cosby for starters, or why the Angoulême festival refuses to acknowledge that women, too, make comics—yet today's feminist comics seem much less radical, less angry, less mobilizing compared with those of decades prior. I for one would like to hear from the aggressive and hilarious Diane DiMassas and Joyce Farmers of the 2010s! Where are those attitudes? Buried deep within the metaphors of fantasy comics like Bitch Planet and Monstress? Or in mild-mannered graphic novels and memoirs like Not Funny Ha Ha or Honor Girl?

I don’t mean to call out these works as being substandard in any way. I like them, and I appreciate what they do. But they exemplify a few things I am frustrated with, and that keep me from relating to comics that are classified as “feminist.”

#1: It seems like the permission for a woman to tell her own story comes with the caveat that it should be a light story—not angry or highly opinionated—and above all, humorous. (After all, there’s nothing as off-putting as a woman who takes herself seriously.) Even though personal stories always have embedded political implications, the narrowness of the storytelling doesn’t always acknowledge that. Memoir comics by women tend to be presented as contained experiences, ones that reassure us: “This is just my story. No more, no less.”

Honor Girl is a good example of this—there’s a quietness in the way this intimate story of teenage love unfolds. And although quietness is fine as a function of human behavior, within this book it communicates a passive and isolated experience. In that there’s a failure recognize that individual struggles are, in fact, connected to a much bigger picture. Honor Girl is shaped—whether the narrative acknowledges that or not—by greater factors than the actions of its characters. These factors in general set the stage for the conflicts and motivations that make for good storytelling. In Honor Girl, they lie at the intersection of gender and sexuality, and class status and Southern culture, articulations that are all but overlooked in the story.

#2: There are some major middle-class assumptions about the circumstances surrounding female empowerment and equality.

For example, when Not Funny Ha Ha talks about two experiences of abortion—one medical and in a rural setting, the other surgical and in a city—it misses the obvious acknowledgment that in a lot of parts of the United States women still struggle for access to abortion. Individual states have all sorts of restrictions that make the average abortion narrative a far cry from the book’s account: mandatory 24-hour waiting periods, parental notification, ultrasounds and counseling from anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers whose goals are to dissuade women from having abortions. For many low-income or working-class women, it’s not so easy to take time off of work, which leaves many with the choice between having an abortion and keeping a job. Perhaps most mind-boggling, in South Dakota, doctors today are required to tell abortion patients that they have an increased risk of committing suicide after their abortion, even though there is no evidence to support this.

In the majority of locations across the country, abortion is not at all available in the manner described in Not Funny Ha Ha. Abortion rights are astoundingly still under attack today, and the lack of this acknowledgment makes the book read as less feminist, less political, less about women’s health and rights, and more like an illustrated best-case scenario of abortion from a middle class perspective.

#3: Much of the fantasy or sci-fi feminist comic books I’ve read depict women’s power as though it is just like a man’s power—violent, or sexually hungry and emotionally callous. These female characters read just like male characters, but with full pouty lips, great tits, and sexy outfits. And they develop strength only as a reaction to some trauma or abuse they’ve experienced, so that female strength is tethered to victimhood.

Although as of this writing there are only three issues of Monstress on the shelves and the main character Maiko’s story is still unfolding, it’s clear she has suffered and survived several traumas: a war, the murder of her mother, a stint in slave camp, and a severed left arm. As a character we know her to be powerfully violent, but her physique is beautifully lithe. She is gracefully thin with a face that looks surprisingly like model Brooklyn Decker, and perfectly blown-out hair. Is this what a refugee survivor of war and dismemberment looks like? Although the world of Monstress is a matriarchy, dominated by women, not men—and this is perhaps the reason this comic is considered feminist—the characters’ motivations are in line with classic tropes of power that are just mirrored versions of the patriarchal world we know now. What’s feminist about that?

We seem to be experiencing a moment when all it takes for a comic to be classified as “feminist” is a woman author who tells her own story, or when female characters embody male-centric tropes of strength and power. That’s pretty limited criteria. I want better feminist comics than that, and that means demanding more complex and challenging narratives and characters. I don’t want feminist characters to read as “angry women” or “violent women,” but self-aware, articulate women who laugh, fart, and give birth way more often than they roundhouse kick. They should be confident enough to say that though this is my story and experience of the world it is sadly not unique because—let’s face it—we live in a patriarchy that devalues things like women’s health, women’s professional success, and women’s voices that dare say things like, “I was raped.” Feminist comics should poke and provoke more than they do right now. They should confidently point out injustice, and tell hard truths. They should be willing to demand things, and to overstate those demands. To be wrong sometimes.

It’s okay to be critical of the things you care about, and that’s the permission I’m giving myself to be critical of what are categorically called “feminist comics” these days. It’s nice to see that there are now more comic artists who are women, or more female comic book characters, but we should know that we’re not “losing ground” if we question—for example—when an all-male production team creates an all-female comic book series, like Paper Girls. Or why so-called feminist characters are very often depicted with huge tits and tinier-than-possible waistlines. When “they talk about women” I want to feel like they’re talking about me so that I feel compelled to respond and engage in ways that aren’t as critical as this essay is. Right now, it feels like feminist comics are talking about someone else.

This essay is an expanded and revised version of one included in the exhibition catalog for Our Comics, Ourselves: Identity, Expression and Representation in Comic Art, on display at Interference Archive, January 21-April 17, 2016.