Connecticut became a state back in January of 1788. By the 20th century it was a haven for artists, writers, actors---and cartoonists.

One of the earliest cartoon settlers was Art Young, very liberal fellow, a socialist and an admirer of Eugene Debs. Around 1900, Young who drew political cartoons for the socialist magazine, The Masses, purchased four acres of farmland in Bethel, Connecticut. His drawings making fun of bankers and Wall Street brokers got him in trouble with the government and charges of sabotage during the World War I years. But he went on to have a long career and sold cartoons to more acceptable magazines like The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post.

By the 1920s, the towns that comprised Fairfield County, the county closest to New York City, which was the East Coast center of book publishing, newspaper syndicates, magazines and the theater. Towns like Westport, Norwalk, Stamford, and Fairfield were still relatively cheap to live in, they had rural charm and quiet while yet offering access to the nearby metropolis of Manhattan.

Residents included John Held, Jr., the glorifier of the '20s flapper; Henry Raleigh and Harold Von Schmidt, magazine illustrators; Perry Barlow (of the brand new The New Yorker); Garrett Price (The New Yorker); and Robert Lawson, author and illustrator of The Story of Ferdinand.

In later years, as we’ll see in this series, comic book artists, comic strip artists, and magazine gag cartoonists flooded the state. Alex Raymond, Austin Briggs, Leonard Starr, Stan Drake, John Prentice, Gill Fox, Orlando Busino, Jerry Marcus, Dana Fradon, Ramona Fradon, Harold Gray, Mort Walker. Dik Browne, Bob Weber, Hardy Gramaty. The Famous Writers School, and later the Famous Artists School and the Famous Cartoonists School, were established in Westport, the latter two by the inventive, hustling, and dynamic Albert Dorne.

Although born in New Rochelle, New York, Alexander Gillespie Raymond and his family were living in Stamford, Connecticut, a few years later. One of the most influential cartoonists of his generation, he was also one of the few cartoonists who drew four very successful comic strips—Flash Gordon, Jungle Jim, Secret Agent X-9 and Rip Kirby. In 1930, the young Raymond was laboring in the King Features bullpen in New York City and commencing an association with the Young brothers, Lyman and Chic. The elder Young brother. Lyman was blessed with only a minor talent for drawing and had he not been related to the more successful Chic, he might well have been jerking sodas in a drug store or peddling encyclopedias door to door in that Depression year.

Up until 1929, although he’d been interested in drawing since childhood, Raymond had never had any ambition to be a comic-strip artist. Although he did want someday to be a magazine illustrator. He studied at the Grand Central School of Art in Manhattan while working in a brokerage firm. One of the effects the Depression had was on Raymond’s employment; he was fired. He said later, “After losing my job, I went to work for Russ Westover.”

Westover had been doing the successful working-girl strip Tillie the Toiler for the Hearst’s King Features Syndicate since 1921 and employing a succession of assistants and ghosts. A neighbor of the Raymond family, he hired Alex at the salary of $15 per week. The next year Raymond ghosted Lyman Young’s Tim Tyler’s Luck. A much better artist than Lyman—and who wasn’t?—Raymond converted it to the adventure strip the syndicate wanted. When the setting changed from an airport to the African jungles, Raymond handled all that and did his first adventure strip. He continue to improve, moving toward the style he would use a few years later. Lyman never again drew it, although he signed the strip for several decades.

King general manager Joe Connelly assigned Chic Young to a new strip in 1930, one to be christened Blondie. At the outset Blondie was a featherbrained twenties gold-digging flapper. Then along came Dagwood Bumstead, a rich man’s son and a nice fellow, though not exceptionally bright. Love changed him and he became determined to marry the girl. His parents objected but he defied them and continued to pursue the woman he loved. Chic Young switched from the joke-a-day format to using continuities. Blondie grew wiser and by the time the couple married it was clear that she was going to be the head of the household.

Late in 1931, Alex Raymond switched Young brothers and was now assisting on and then ghosting Chic’s new strip. He depicted all the events leading up to their impressive church wedding. He then followed the newlyweds into domestic bliss. Dagwood was an office worker and Blondie was a practical housewife. He was getting closer to the comic strips that would earn him the title of one of America’s Great Comic-Strip Cartoonists.

While Raymond was handling various chores in the King bullpen, along came a new kind of adventure strip that was affect the course of his life and that of King Features. Chester Gould, until then a second-string cartoonist, sold Dick Tracy to the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate. Tracy was tough, impatient, and honest. Comics historian Jay Maeder has written, “Dick Tracy was an instant sensation and proceeded to remain in the first rank of comic strip properties for many years.” His hardboiled dick made Gould a rich man and brought in admirable profits to the syndicate.

Rival syndicates were somewhat slow on the uptake and it wasn’t until 1933 that Connelly at King Features got around to launching some competing tough-cop strips. One of the writers he approached was Dashiell Hammett, author of such hardboiled detective novels as The Maltese Falcon and The Thin Man.

For the handsome sum of $500 a week Hammett was hired to create a comic strip. The result was Secret Agent X-9, who was a rather unconventional agent of the FBI. The new strip was a daily only and debuted in January of 1934. Sales material sent out to newspapers described Hammett as “today’s most popular, fastest-selling author of detective novels.” For the artist Connelly plucked Alex Raymond out of the bullpen. In the sales pitch, he was described as “the sensational new illustrator.” His salary was $20 a week.

Raymond’s work had improved considerably from his Tim Tyler days and he was soon using a vigorous dry-brush approach that suggested that used in many of the detective pulp magazines of the day. And the next year he had hired Austin Briggs, a magazine illustrator, as his assistant.

Hammett was eventually fired from X-9. A magazine reported that he was let go “when he lagged behind schedule, with ideas that lacked the power of his printed work.” Raymond left the secret agent late in 1935 to devote all his time to his two Sunday pages.

Again Joe Connelly became inspired by an earlier comic strip, Buck Rogers. It had first appeared early in 1929 and was later dubbed “one of the worst-drawn features in comics history.” But Buck brought into the open ideas that had been showing up in pulp magazine for years and his adventures hinted at what would be happening in the future, such as space travel and the atomic bomb. It was adapted from a short novel that had been in Amazing Stories in its August 1929 issue. The art, such as it was, came from Dick Calkins. As ungainly as the strip was, it sold very well. The strip Connelly decided on was Flash Gordon. He need a writer to develop his idea and hired editor/writer Don Moore, who was in charge of the Argosy-All Story pulp. Moore worked with, and sometimes rewrote, such fantasy and science fiction names as A. Merritt, Otis Adelbert Kline, and Edgar Rice Burroughs.

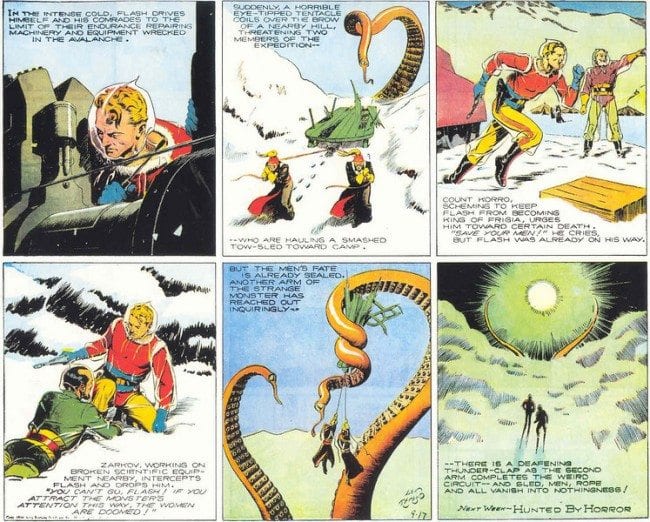

Moore’s obit in the New York Times for April 9, 1988, had this to say about him: “In 1934 he was editing Argosy-All Story, which published adventure, detective, and mystery stories. King Features, which wanted a comic strip to compete with the futuristic Buck Rogers strip, called on him, and Mr. Moore was hired on a $25 week-to-week basis to write Flash Gordon, which was drawn by Alex Raymond.” Several recent comics historians have credited Raymond with creating and writing Flash Gordon. But such is not the case As the bleak decade of the 1930s progressed it became obvious that a second World War was coming, and "the Orient" was perceived as a potential threat. Flash and his companions would, on the planet Mongo, tangle with its maniacal ruler Ming the Merciless. As his title implies, he wasn’t an easy fellow to get along with and was a simulacrum for that famous sinister Oriental villain, the insidious Dr. Fu Manchu. In his first years of plaguing the planet, Ming's skin tone was a conspicuous yellow. An important influence on the strip was Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars. He’d appeared first in an All-Story pulp serial published as the novel A Princess of Mars in 1917. Carter was mystically transported to the Red Planet, known to the locals as Barsoom. Flash’s Mongo was quite a bit like Carter’s Barsoom; both locales mixed futuristic trappings with 19th Century props found in Ruritanian novels. Princesses rubbed shoulders with fascist dictators, giant reptilian monsters swam beside giant submarines. Fellows fought with swords and ray guns.

An equally important source of inspiration was the science fiction novel When Worlds Collide, plotted by Edwin Balmer and written by Philip Wylie. It was serialized in Blue Book, which Balmer was editing, in 1932. The basic threat was that a rogue planet was going to collide with Earth and destroy it. There was only time to construct one spaceship, which would, like Noah’s Ark, carry some folks to safety. In a fine use of funny-paper science, the initial Flash Gordon Sunday page (January 7, 1934) introduces Dr. Hans Zarkov, “who is laboring day and night… to perfect a device with which he hopes to save the world.” This device is a spaceship that the eccentric scientist has built in his backyard. This is what scientists had to do in those pre-NASA days.

Zarkov intends to smack his ship into the deadly comet and send it away from Earth. Just as he is about to blast off, an airliner comes flying low over his property, about to crash. Aboard are “Flash Gordon, Yale graduate and renowned polo player, and Dale Arden, passenger.” The somewhat unbalanced Zarkov hustles them aboard his rocket to help him knock out the fast approaching planet and “with a deafening roar the rocket shrieks into the heavens.” Coming to his senses Zarkov decides he won’t destroy himself or the lives of his conscripted crew. He will instead fly to Mars and land there. The space flight will only take a few days and he’s fairly sure it has an okay atmosphere. He, too, must be getting his information about the heavens from pulp magazines.

Alas, they miss Mars and land smack dab on Mongo. They are captured by Ming and Dr.Zarkov finds out that he is the one sending the planet to destroy Earth. He manages to persuade the tyrant to call that off and then Flash and the others escape from Ming’s palace.

Raymond improves considerably as Flash Gordon moves further into the '30s. His layouts and staging are better, and the flow of the action is smoother. Flash, Dale, and Zarkov travel the length and breadth of the planet, facing dangers in Arboria, a great city in the trees, encountering lion-men and then hawk-men, dwellers in “a city suspended in space.” (These winged fellows, by the way, were quite obviously an inspiration to writer Gardner Fox when he invented Hawkman for Flash Comics in 1940.) Later, Flash is captured by Queen Undina and forced to spend time in her underwater kingdom. An operation allows him to breathe underwater though no longer on land.

By the middle 1930s, Raymond has moved even closer to the striking style associated with him. In the Nostalgia Press reprint of some of two years of these pages, comics historian Maurice Horn called them “a bravura display without parallel in the history of graphic arts.” During 1939, however, Raymond said goodbye to the pulp magazine influences on his drawing style. The drybrush inking was left behind and the drawing became more naturalistic, Flash struck fewer heroic poses and Dale less sultry ones. Don Moore’s prose, though, remained unashamedly clunky. Although beyond draft age, Raymond enlisted in the Marines in 1944, and Austin Briggs assumed the page and stayed with it for four years. He didn’t bother to sign it.

Raymond also left behind Jungle Jim, the topper to the Flash page. Jim Bradley was a “trapper, hunter, explorer” who was probably based on Frank “Bring ‘Em Back Alive" Buck, a popular self-exploiting big game hunter of the '30s. Jim plied his trade in the jungles, but not those of Tarzan’s Africa. He hung out, like Buck, in Malaya, Sumatra, Borneo, and many of the South Seas islands. His basic outfit consisted of riding breeches, pith helmet and boots. Jim’s sidekick was named Kulu and was at the start the hunter’s servant and called him Tuan. The strip improved in appearance along with its downstairs neighbor. During the war, Jungle Jim was recruited by the U.S. government and handled espionage work, eventually becoming an Army captain. Kulu put on a shirt and dropped the pidgin English.

When Alex Raymond returned from the Marines, he found that King Features was satisfied with the job Briggs was doing on Flash Gordon. They offered him a brand new strip that was cooked up by longtime syndicate editor and mystery writer Ward Greene. Rip Kirby was a daily-only strip about a tough but sophisticated private eye based in Manhattan.

Raymond, offered a substantial guarantee, decided to bid farewell to outer space. He prepared a month of dailies for the syndicate salesmen. They were enthusiastically accepted by Greene and King Features. The first weeks of the strip represent a great leap forward for him. His new style is a mature one, with no more heroic poses and a somewhat film noir approach. All in all, Raymond had reached a new level. Rip Kirby sold well, picking up almost one hundred newspaper clients almost immediately. It began on March 6, 1946. Kirby, like Ellery Queen, was an intellectual. He even wore glasses and, like Raymond, he was a former Marine. He lived in a posh New York City apartment, had a piano and a valet named Desmond, who just happened to a reformed thief. His blonde lady friend, Honey Dorian, was gorgeous enough to be a fashion model and soon became one.

The daily strip remained successful and King wanted Raymond to add a Sunday page for an increase in salary of $35,000 a year. He turned that down, explaining that it would be too much additional work. The Rip Kirby sequence that was running in the fall of 1956 had begun on July 30th and when September 6th arrived was halfway from its conclusion. The next day’s New York Times ran the following obituary---CARTOONIST DIES IN WRECK OF AUTO Did “Rip Kirby” and “Flash Gordon” Was Marine Combat Artist Westport, Conn. Sept 6---Alex Raymond, cartoonist, was killed when a sports car he was driving overturned on a wet street and crashed into a tree. A passenger was killed.

The events leading up to this obit were told in comics historian Richard Marschall’s The Great Comic Book Artists. "On a rainy day in 1956, Raymond visited [Stan] Drake’s Westport studio while his Mercedes SL Gullwing was in the shop having platinum plugs installed. Raymond expressed interested interest in driving Drake’s new Corvette, and the pair hit the wet, winding roads around Green’s Farms. Forty-five miles an hour hardly seems like an excessive speed, except on the glorified paths of rural Connecticut. Raymond at the wheel, hit a turn and a dip on Clapboard Hill Road, and the sleek Corvette arced sixty-five feet in the air… before crashing into a tree, Raymond was killed instantly, Drake was thrown thirty feet and severely injured.” In the several accounts that have appeared over the years, some have stated Raymond may have committed suicide, mentioning that he had been hospitalized for accidents on his own in recent months and also been suffering from depression. The other passenger in the car was Stan Drake, who was drawing the soap opera strip The Heart of Juliet Jones. He was not a close friend of Alex Raymond but more a colleague who sometimes got together to talk shop. Contrary to the Times report, he was not killed. He told me he was not unconscious directly after the crash, as some accounts said. He woke up lying on the wet grass near his wrecked car and heard someone saying, “This one’s dead.” About the crash itself, Drake remembers that Raymond misjudged and when he realized they were heading right for a large tree, he meant to hit the brakes but instead stepped on the gas.

While saddened, King Features still had to keep Rip Kirby going and got someone to take it over at once. John Prentice was the artist who took over and this is how, according to Leonard Starr, it came about. “Johnny and I shared an apartment in Manhattan… we worked for Johnstone and Cushing, but I was shopping around some comic strips to syndicates (including On Stage). Then one day, we got word that Alex Raymond had been killed in a car crash. I received a call from Sylvan Byck… He told me that Raymond had worked only two days ahead and the syndicate was in a panic. Could I come over and take up Rip Kirby where Raymond left off? I thought about it… Rip Kirby was a sure thing, but I decided to take a chance and try my luck with my own strip a while longer. So I told Sylvan, ‘You don’t want me, but the very best guy in the world for the job is sitting right next to me’ Sylvan responded, ‘Send him right over!’ And that’s how Sylvan met Johnny and Johnny got the Rip Kirby strip.”

While saddened, King Features still had to keep Rip Kirby going and got someone to take it over at once. John Prentice was the artist who took over and this is how, according to Leonard Starr, it came about. “Johnny and I shared an apartment in Manhattan… we worked for Johnstone and Cushing, but I was shopping around some comic strips to syndicates (including On Stage). Then one day, we got word that Alex Raymond had been killed in a car crash. I received a call from Sylvan Byck… He told me that Raymond had worked only two days ahead and the syndicate was in a panic. Could I come over and take up Rip Kirby where Raymond left off? I thought about it… Rip Kirby was a sure thing, but I decided to take a chance and try my luck with my own strip a while longer. So I told Sylvan, ‘You don’t want me, but the very best guy in the world for the job is sitting right next to me’ Sylvan responded, ‘Send him right over!’ And that’s how Sylvan met Johnny and Johnny got the Rip Kirby strip.”

Although Stan Drake had a long, varied, and mostly successful career as a cartoonist in his own right, he had also become a perennial footnote to any account of the life of Alex Raymond. Born in Brooklyn in November of 1921, he was the son of a transplanted British radio actor, Stanley Allen Drake, Sr. From an early age addicted to drawing, he studied at the Art Students League in New York City, where one of his instructors was George Bridgman, the leading teacher of anatomy and figure drawing. While still in his teens, Drake sold illustrations to pulp detective magazines. A fellow student at ASL was Bob Lubbers, who also did very well in comic books and comic strips. He’s said, “My pal and I Stan Drake left Bridgman’s life class and marched down to Centaur (a short-lived publisher) and sold them some comic book features we’d created.” Drake didn’t do as well as his chum, but did sell a few things. He also worked for the Funnies, Inc shop and drew briefly for Timely.

After spending the World War II years in the service, seeing action in the South Pacific, he was discharged in the late winter of 1946. He didn’t return to comic books but signed up with the Johnstone and Cushing studio. They were the largest producer of comic book and comic strip advertising for ad agencies and his fellow artists included Dik Browne, Elmer Wexler, and Gill Fox. In 1953, Fox who sometimes functioned as a matchmaker, suggested Drake to Eliot Caplin, writer of such comics strips as Abbie an’ Slats , who was looking for an artist to illustrate his new soap opera strip, The Heart of Juliet Jones. A palpable hit, it soon rivaled Mary Worth and could be followed in several hundred newspapers. Richard Marschall praised its “sophisticated story lines and outstanding artwork.” He also praised Drake’s knack for drawing beautiful and stylish women.

Drake, like some of the focal characters in his soaper, was a romantic fellow and much married. This, as might be expected, resulted in his having to pay alimony to two or three ex-wives. And that prompted him to take on more art jobs. Changing styles, he also drew Blondie, daily and each Sunday, for well over a decade. For a time he also ghosted Al Capp’s Li’l Abner and traveled to Capp’s studio in Boston fairly often. A high point in his career was a series of five graphic novels starring Kelly Green, written by Leonard Starr and illustrated by Drake in an excellent version of his style, which clearly showed his enthusiasm for the character. Richard Marschall was the involved with the project and had been hired by the French publisher Dargaud when they opened a New York office. The five graphic novels were aimed at grownup audiences and featured violence, bloodshed and sexy women in interesting shades of undress. Kelly herself was often seen in her lingerie or less. The European format allowed Drake and Starr to do stuff that their newspaper strips wouldn’t allow.

They were sharing a second-floor studio in Westport. It was near a movie theater and upstairs from an art supply store where they both had charge accounts. It was the most smoke-filled of smoke-filled rooms and both of them, dedicated cigarette smokers, looked as though they were working at their drawing boards surrounded by a thick London fog.

They were sharing a second-floor studio in Westport. It was near a movie theater and upstairs from an art supply store where they both had charge accounts. It was the most smoke-filled of smoke-filled rooms and both of them, dedicated cigarette smokers, looked as though they were working at their drawing boards surrounded by a thick London fog.

The above mentioned John Prentice had a separate office in back of theirs, also smoke-filled. As time went by, Drake developed a serous drinking problem and most days from noon until late afternoon could be found at a Post Road restaurant a few blocks from where the studio had been, mostly slouched at the bar. He wasn’t doing much drawing and finally was persuaded to enter a detox program at the Norwalk Hospital. Unfortunately he never left the place and passed away there on March 10, 1997.