The revolution will not be televised

The revolution will not be televised

The revolution will not be brought to you by Xerox

- Gil Scott-Heron, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised (1970)

The humble, photocopied minicomic sprang into being in the early 1970s and has become a prime engine of creativity in a vast subculture that today includes thousands of comics creators. This edition of Framed! offers a glance at minicomix with an essay, a book review, and an exclusive video premiering the first episode of “Comic Books and Pie.”

As its name suggests, the minicomic (or, “mini-comic,” as the term is sometimes spelled) is a modest form of comics: a miniature comic book. The minicomic is not to be confused with fanzines, which offer writing and illustration about comics. Minicomix (the plural form is sometimes spelled with an “x,” a nod to the form’s antecedent: underground comix) are usually self-published, have extremely limited distribution, and are passionate labors of love.

Minicomix rarely make money for anyone and almost never garner attention from mainstream critics (a recent, jaw-dropping exception is "Drawn Together," the three page article by Robert Rhee about the monthly Seattle minicomix event called DUNE, published in the January 2016 issue of Art in America). And yet, they are joyously, enthusiastically produced. Perhaps part of the reason for this is that, over the years, minicomix have fostered healthy connections between people who love comics. This infusion of vitality and goodwill associated with the minicomic is a significant, if invisible, force in the current thriving state of comics in America.

During its roughly 45 years of existence, the modest minicomic has nurtured numerous notable creators, including: Peter Bagge, Donna Barr, Lynda Barry, Marc Bell, Chester Brown, Kevin Eastman, Brad Foster, Rick Geary, Justin Green (often credited as the inventor of the minicomic), Roberta Gregory, Bill Griffith, Matt Groening, Wayne “Wayno” Honath, Peter Laird, David Lasky, Bill Loebs, Jason Lutes, John Porcellino, Ronald M. Regé, Jr., Trina Robbins, Art Spiegelman, Colin Upton, Jim Valentino , Joe Zabel, and Dan Zettwoch, to name a few from mostly the first decades of the minicomic's history. Some of these folks have dabbled in the form; others have made it a core part of their repertoires.

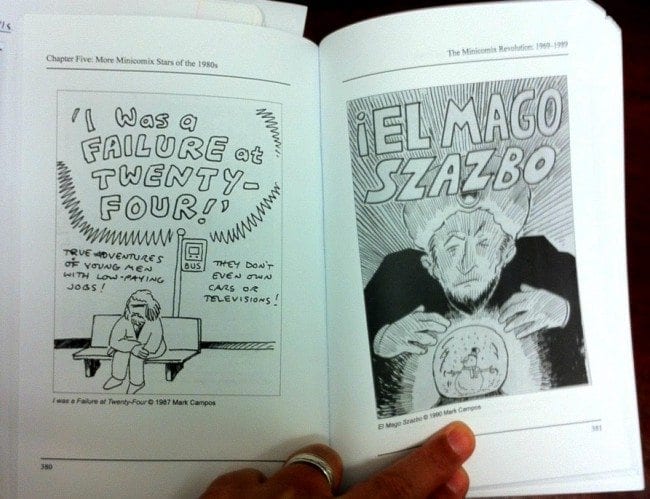

Among the minicomix of visual storytellers and outrageous gagsters like Mark Campos, Max Clotfelter, Clark Dissmeyer, Matt Feazell, Par Holman, David Miller, J. R. Williams, Steve Willis, and Jeff Zenick (to name some personal favorites of mine that aren’t – but should be – widely celebrated), one finds pockets of cloistered coolness that, once absorbed, can expand and transform ideas about comics.

Extolling the Virtues of the Minicomic

Thanks to microscopic print runs and abysmal distribution, the minicomic remains largely underground. The semi-hidden nature of the minicomic -- almost completely an anti-commercial enterprise -- allows for great freedom. In 2015, the form is exploding with a surge of creative vitality. This is spurred and churned by the self-publishing tools of the Internet, a growing population of comics literate readers, and the widespread acceptance of comics as a valid and socially respected form of personal expression. Younger practitioners respect comics and no longer see them as merely about superheros, media spin-offs, and the frustratingly platonic adventures of the inhabitants of Riverdale. Older folks who have been making these diminutive alternative comics for decades have gained a new coolness.

The form of the minicomic has been, and continues to be, one of the most welcoming entrances into the world of creating comics. For some, making a minicomic is a stepping stone to professional work and much wider distribution. For others, minicomix are an end in themselves -- many accomplished mincomix creators remain known only to a few (mostly other minicomix creators). For many other people (more today than ever before I suspect) making minicomix is solely about fun and community, the way one might knit a sweater or play a board game with friends.

Termite Art (1)

At their best – and this is why I find them so interesting – minicomix are, to use Manny Farber’s famous terminology, “termite art.” In his seminal 1962 essay, “White Elephant and Termite Art,” Farber writes:

“Good work usually arises where the creators… seem to have no ambitions towards gilt culture but are involved in a kind of squandering-beaverish endeavor that isn’t anywhere or for anything.”

To this point, Mark Campos, a Seattle cartoonist and writer who has produced several notable minicomix since 1987 recently told me a story about teaching a class in the 1990s on how to make a minicomic. Afterwards, someone asked him: “how can I make money doing this?” As Campos told me this story, he looked as gently amused as a Buddhist teacher who had been asked how to make money from being kind to others. He knew that I understood: minicomix are almost never made with the intention to generate profits.

Farber goes on to say:

“A peculiar fact about termite- tapeworm-fungus-moss art is that it goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.”

Aside from coincidentally (or, perhaps not) representing a striking description of a particular goopy ethos one encounters in many modern practitioners of comics who delight in depicting voracious slimy tapeworms, oozing pustules, and conquering blobs of hairy mold, this is the viewpoint that connects my interests in what might seem to be disparate strains of comics.

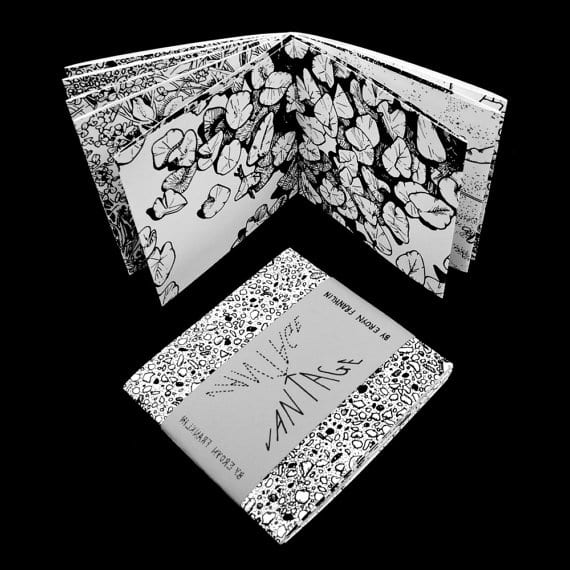

Through this lens, there is little difference between writing about, say, the little-known Percy Winterbottom comics of 1897 and, say, Eroyn Franklin’s Vantage minicomic from 2012. Both gnaw hungrily at the borders, and my mission as a historian-writer-critic is to champion that “eager, industrious, unkempt” mastication.

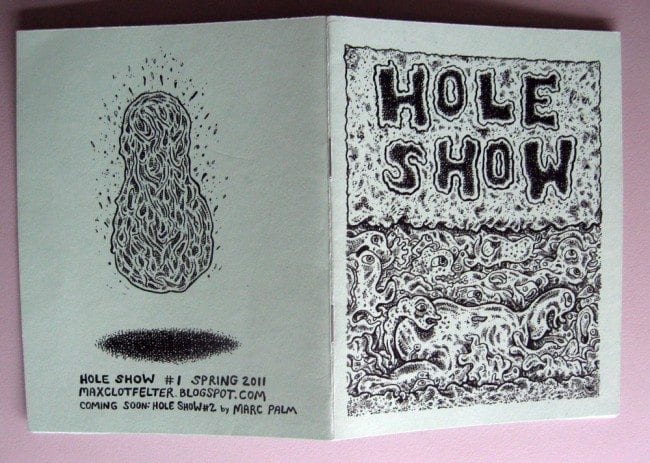

The Minicomic: Then and Now

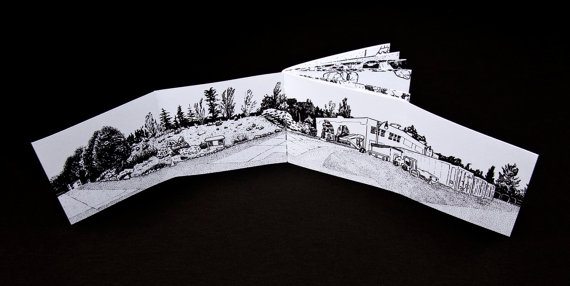

Today, the term “minicomic” appears to apply to any hand-made, self-published, D.I.Y. comic book or illustration album. The “mini” part corresponds to the size of the print run, which is usually small – fifty or a hundred copies. Size and format don’t seem to be a part of the modern definition for that term.

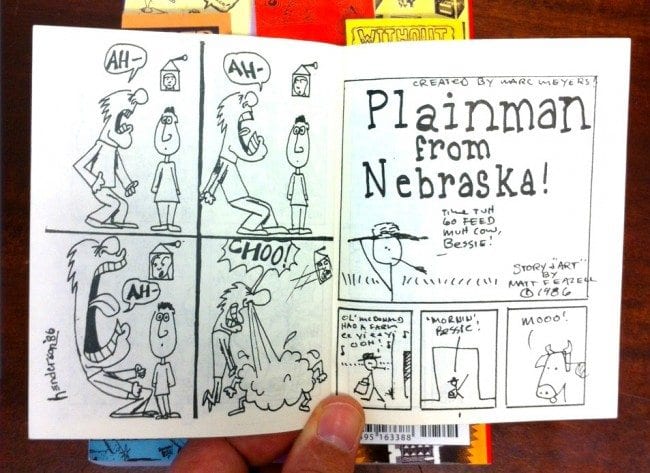

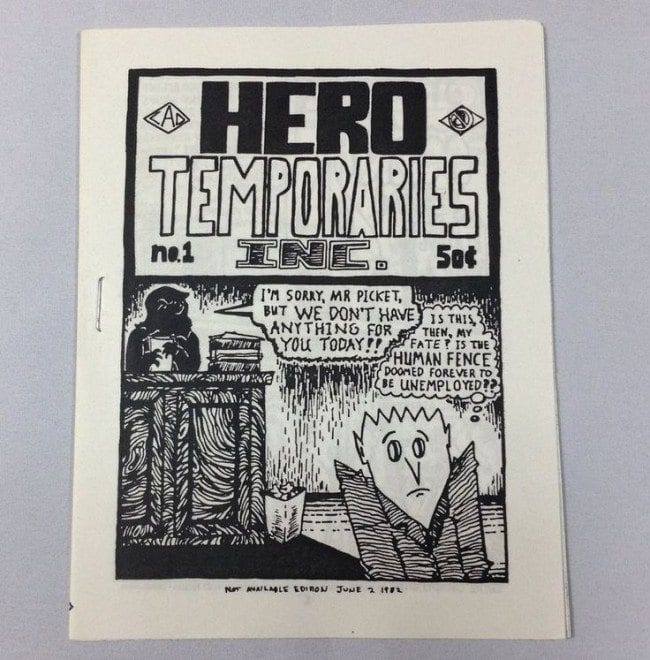

However, back in the 1980s, “minicomic” usually referred to a very specific format: a miniscule booklet, usually 8 pages long and 4.25 inches wide by 5.5 inches tall (“Digests” were 5.5 inches wide x 8.5 inches tall).

Minicomix were ingeniously and economically made by folding a sheet of standard size (8.5 x 11 inches) paper in half, and then folding in half again. A little cutting and stapling and there you have it. The beauty of this is that you can cheaply and easily make a complete comic book at the nearest photocopy machine by simply printing a sheet of paper front and back – a huge advantage for self-funded ventures.

An additional beauty of the original minicomic format is that it literally folds in on itself, compressing and purifying. Put another way: you can’t get too carried away, drawing in a few tiny pages. Unnecessary elaboration is mostly stripped away. The format gives the inexperienced comic artist much-needed structure and encouragement (the wonder of holding your own comic in your hands for the first time is, for some, comic book crack), and the experienced artist can work with it the way a skilled poet works with a sonnet or a haiku.

Another meritorious aspect to the original mini format is that, with some – but not too much -- effort and determination, one can start and complete an entire book in a single session. It’s just eight tiny pages – and really, just six pages if you do a cover and leave the back cover artistically blank. Not easy to make in one session – but possible. Numerous minicomix creators of the 1970s and 1980s (including yours truly) made 24-hour comics long before the term was coined in 1990 by Scott McCloud.

Today, minicomix are not just those halved-twice booklets. They are digest-sized (5.5 x 8.5 inches) books, thick and perfect-bound full-size comics, and all manner of interesting sizes and formats. The term has evolved and perhaps become a bit diluted. But, it’s no great matter. The true value of minicomix lies not in the form, but the spirit.

Underneath it all, the do-it-yourself, punk attitude of the minicomic persists – no matter what form it may take. When you reach deep and fill up a book, and then shell out your hard-earned cold cash to print copies, you damned well know that it’s yours – and you can make comics about whatever the hell you want to – there’s no editor, publisher, distributor, or Comics Journal critic with which to contend. It’s you and the Muse, baby.

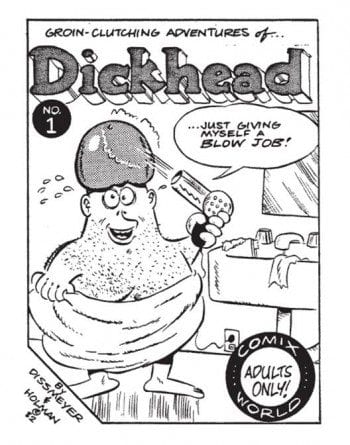

This freedom makes minicomix a mixed bag. Frankly, a fair amount of minicomix are under-developed and just plain boring to read. Because the form attracts beginners who are often young, there’s an awful lot of sophomoric content that quickly loses its charm, if it ever had any to begin with. Drugs, vomit, naïve political stuff, and phalluses – lots of bulging, veiny, spurting members – populate this form, perhaps in a filial connection to the bootleg Tijuana bible sex comics of the 1920s through the 1960s, also small, eight-page comic books (sometimes called "eight pagers").

One often finds in the mixed bag of minicomix skillful renderers with no stories to tell. They draw one incredible image after another, but cannot muster coherent, sustained narratives. Conversely, one can find gifted storytellers who have no drawing ability or penchant for visual storytelling -- good ideas that are buried in unappealling art. Among this vast mish mash, one might apply the great writer Theodore Sturgeon’s Law, that “ninety-percent of everything is crud.”

When, among the piles of photocopied and hand-stapled booklets, you can find the good ten percent it’s often going to be something new and different, and damned well worth some attention. There are many sparks of embryonic creative brilliance to be found among these modest eight-pagers.

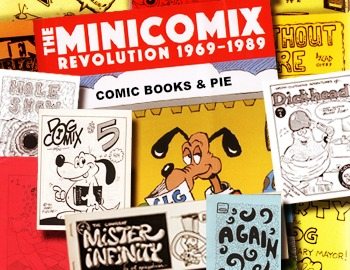

The Minicomix Revolution 1969-1989 by Bruce Chrislip

Which brings me to The Minicomix Revolution 1969-1989 by Bruce Chrislip. Incredibly, someone has written a history of minicomix! This thick, 462-page trade paperback volume Chrislip self-published in July, 2015 serves as a helpful guide in finding and appreciating some of the better minicomix of the past. In addition, it provides a valuable framework for understanding – and further discussing -- the history of the form. And, lastly, it offers Chrislip’s fond memoir of the minicomix culture during roughly its first couple of decades.

Which brings me to The Minicomix Revolution 1969-1989 by Bruce Chrislip. Incredibly, someone has written a history of minicomix! This thick, 462-page trade paperback volume Chrislip self-published in July, 2015 serves as a helpful guide in finding and appreciating some of the better minicomix of the past. In addition, it provides a valuable framework for understanding – and further discussing -- the history of the form. And, lastly, it offers Chrislip’s fond memoir of the minicomix culture during roughly its first couple of decades.

Chrislip's book provides valuable, heretofore unobtainable context for understanding the bewildering, obscure world of minicomix. He should get a golden stapler for this book.

Bruce Chrislip has been active in minicomix almost since the birth of the form. In 1973, Chrislip encountered his first minicomic, Tales of the Enemy #3, created and self-published by Joe Zabel, who would go on to become a prime collaborator of Harvey Pekar’s (with inker Gary Dumm).

At the time, Chrislip and Zabel were attending Youngstown State University in Ohio. In the true minicomix spirit, the back cover of Zabel’s minicomic invited fellow comics creators to contact him for help in making their own minis. Chrislip and his friend Topper Helmers each separately took Zabel up on the offer. Chrislip details his first encounter with Joe Zabel in The Minicomic Revolution 1969-1989:

“He (Zabel) had the bohemian look of long, scraggly brown hair and a somewhat unruly beard…Topper had seen Joe first, possibly even the day before, and he warned me that I might get the bum’s rush, as he had. I asked Joe about this and he told me that Topper had stumbled into the office just at the point that he was trying to impress an attractive young girl. But Joe and I hit it off pretty well, entering into a conversation about comics. He explained how Tales of the Enemy had been printed using a process known as paper master offset. The specially coated pieces of paper that one drew on became the actual printing plate.”

As the book moves through its history, we learn about Chrislip’s life. For example, in 1981 he moved to Seattle by way of Cincinnati, just in time for the transition of the city into a cartoonist’s Mecca:

“When I got to town I looked up minicomix artist Wayne ‘Bover’ Gibson… A few hours after arriving in Seattle and finding Wayne’s apartment, we were drawing a minicomic with the offbeat title of Penguins in Bondage.”

In Seattle, while living on food stamps, Chrislip started publishing City Limits Gazette in 1981. Running until 1986, it was one of the premier zines of the time that reviewed minicomix and interviewed practitioners of the form. The zine published the first-ever interview with Harvey Pekar.

Chrislip’s bits of memoir are skillfully woven among a broader, more objective history of minicomics. He starts with the progenitors of the form: Tijuana bibles and includes promotional miniature comics like The March of Comics, a 488-issue series shoe stores gave away (get it – March of Comics?) from 1946-1982, and which included “Maharajah Donald ,” the classic Carl Barks story in issue #4.

Chrislip spends some fascinating time delving into the undergrounds and what one could call the first “true” minicomic, created in 1969 by Leonard Rifas in California (who now lives and teaches in Seattle, WA):

“Leonard Rifas had the right idea in the late 1960s – publish your own. On 1969, Rifas hired Don Donahue to print 1,000 copies of a 12-page comic called Quoz.”

Taking a rare day off from my PowerPoint presentation design business, on October 31, 2015, I was able to purchase, for five dollars, one of those original thousand copies from Rifas himself, who tabled at the Short Run Comix and Zine Festival in Seattle, Washington offering copies of Quoz from that first 1969 printing, made on the same press that printed Robert Crumb's Zap Comix #1. Without Chrislip’s book, the historical coolness of this comic, an inspired dose of charming surrealism and a terrific comic on its own (sorta makes me think of reading Babar on LSD), would have been lost on me! I wonder how many of the hundreds of people attending Short Run this year knew Rifas is one of the artists who started it all.

The Minicomix Revolution 1969-1989 covers only the first two decades of minicomix history. Chrislip explains that the work, over a decade in the making, would have to be over twice as long to even begin to cover minicomix up to now. A radical underestimation, I suspect. It may be that the full span of minicomix may never be documented. (Steve Willis, a librarian as well as comics master, set up several minicomix and small press zines collections at Washington State University, including the Lynn R. Hansen Underground Comix Collection (123 containers of rare minis, including a few of mine -- I still have my letters from Lynn).

In this book, I learned notable cartoonists like art spiegelman, Bill Griffith, Trina Robbins, and Justin Green made some of the first official minicomix, which hardly sold at all! Spiegelman and Griffith collaborated on a minicomic called Self Destruct: Bulletin of the Suicide Liberation Front that seems to be an important development in a creative partnership leading soon after to their co-edited classic comic series, Arcade.

By far the majority of Chrislip’s history is given over to far less celebrated but nonetheless fascinating minicomix creators. I like how Chrislip mostly stays focused on the cartoonists. Especially valuable are the sub-chapters about the lives and careers of numerous notable minicomix creators. In many cases this information is not available anywhere else. Here’s a sample, from the section on the reclusive Clark Dissmeyer, a personal favorite:

“Dissmeyer was a seventeen year old Nebraska high school student when he saw his first minicomix. He had ordered some minis from Artie Romero in 1980 -- after seeing a plug for Cascade in Heavy Metal magazine and was so inspired that he drew his first minicomic, Plague Humor, in one all-night session. The art was crude but the dark humor was surprisingly effective. The tone was set from the front cover. An angry wife berates her bemused husband: ‘I could have married a respectable man, like a lawyer or a doctor! But no, I had to get hitched to some creep into ‘corpse reanimation’!”

Occasionally, Chrislip moves away from single creators to detail the histories of a few notable titles, such as his nine-page section on Outside In, a fifty-issue minicomic series begun by the seemingly divinely inspired Steve Willis and involving hundreds of others. In some ways Outside In represents the penultimate minicomix project because it engaged hundreds of creators in the act of creating self-referential work.

"It was an artist's project. A rumor. A reality. An obsession. Fifty issues and 447 self-portraits printed from 1983-2003 drawn by artists, writers, poets, friends, lovers, losers, relatives, high school kids, musicians, mystics, scensters, strangers, cartoonists of all ages and abilities. Outside In was over 400 stories about people drawing them,selves as they saw themselves -- or as they wanted to present themselves to the world." (2)

I appreciate that Chrislip does his best – as we see in the above excerpts -- to describe the covers and contents of the literally hundreds of minicomix his book documents. However, it’s hard to get around the fact that one is reading about highly obscure material that – in most cases -- is virtually impossible to read because it was never widely circulated and is today very difficult to obtain.

I have been tracking minicomix on ebay for the last year, and the few that are put up for auction often have shockingly high starting bids, usually around $25 for an eight-page comic that sold for a quarter originally. In September, 2015, a copy of art spiegelman's 1970 minicomic, Compleat Mister Infinity (love that title), printed on a moebius strip and cover priced at ten cents, sold on ebay for $103.50. I don’t argue the valuations made by sellers of what is argruably some of the scarcest comics in America, but I do feel frustrated that I can’t, for example score a copy of Clark Dissmeyer’s Plague Humor, a tantalizing description of which is given in The Minicomix Revolution 1969-1989.

However, I can find a copy of Clark Dissmeyer and Par Holman’s hilarious Dickhead #1 in Michael Dower’s Treasury of Minicomics, Volume One (2013, Fantagraphics). In fact, in that same thick little book, that reprints dozens of rare minicomix, one can find Justin Green's pioneering first two minis that started it all as well as Leonard Rifas’ Quoz, mentioned earlier in this column (although the reprint is smaller than the original and suffers for that), as well as a highly informative essay by Rifas on his minicomic, to boot.

Michael Dowers, the publisher of Starhead Comics - a line of mini- and regular comix and newspapers (The Seattle Star), has tackled what he describes to be the "mind-numbing experience" of sorting through decades of these obscure little books to produce three 800-page plus bricks of minicomix reprints (in the original quarter-page format): Newave! The Underground Mini Comix of the 1980s, Treasury of Mini Comics, Volume One, and Treasury of Mini Comics, Volume Two.

Unfortunately, these books can be challenging to read, printed on thin shiny paper and annotated in a tiny, lightweight font. It's often difficult to divine the names of the creators. However, Chrislip’s new book in hand, beautifully designed and readable, it is now possible to attack the boullion cubes of creativity in Dowers' minicomix series anew. One can get a great deal more out of each of the two ventures when they are put together. Fantagraphics could do worse than issue a broader-reaching second printing of The Minicomix Revolution 1969-1989 to serve as a companion book to their three-volumes-and-counting Minicomics Treasury series.

If I remember correctly, only 500 copies of The Minicomix Revolution 1969-1989 were printed. Perhaps, as a rugged individualist’s nod to the USPS, which once, long ago, brought minicomix creators together, Chrislip has eschewed modern ecommerce methods. If you want a copy, you must mail him a check for $30 ($25 cover price, plus $5 shipping) to:

Bruce Chrislip

2113 Endovalley Dr.

Cincinnati, OH 45244

This book will sell out and vanish in short order. As quickly as, say, the time it takes to read an eight-page minicomic.

Comic Books and Pie, Episode 1

The cartoonist and illustrator James Gill (Cognitive Bias Parade) and I have been drawing and self-publishing minicomix since 1982. Recently, Jim – who has become a video documentarian, among his many other pursuits – wanted to capture me talking comics history during a visit to my home in Seattle, WA.

Relying on the appeal of some cherry pie and vanilla ice cream, I managed to persuade the reclusive Mr. Gill to join me in front of the camera, where we chatted about various minicomix, digests, letters, and other self-published and self-distributed comics randomly pulled from one of my storage boxes. In this episode, we discuss making minis back in the day and look at comics and other stuff by Jeff Zenick, John Porcellino, Jason Lutes, High School Comics, J.R. Williams, among others.

A few notes on this episode:

Jim is correct in remembering there was a Seattle-based publication about minicomics -- it was Bruce Chrislip's City Limits Gazette.

3:35 - The term that Willis and others seemed to prefer over the "Newave comics" is "Obscuro comics."

7:34 - The Factsheet Five like publication from Seattle that Jim and I are trying to remember is Bruce Chrislip's City Limits Gazette.

11:45 - In discussing the John Porcellino spread that has panels of the same shape and size, except for one, the term I was trying to recall is "pre-attentive attributes." These are elements of design based on an immediately perceived difference in a pattern that happens before conscious attention is given. In sequential visual storytelling, pre-attentive attributes are a fundamental design element.

Notes:

Comic Books and Pie was produced by James Gill. and is copyright 2015 James Gill.

All art in this article is copyright the respective holders.

(1) A special thanks to art spiegelman for making me aware of Manny Farber's excellence as a cultural critic.

(2) Michael Dowers published seven issues of Outside In, and includes excerpts and an index of contributors in Treasury of Mini Comics, Volume One