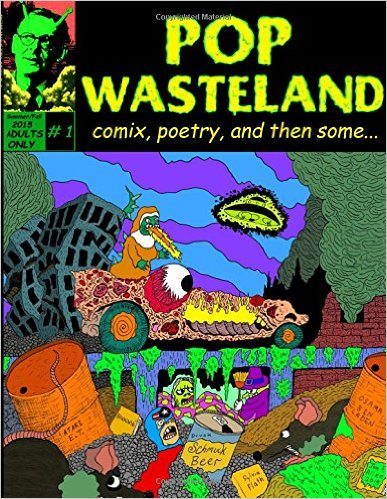

“Having no talent is not enough,” said Gore Vidal about the underground theatrical troupe The Cockettes, following its New York City debut. Neither, it seemed, were bestiality, cannibalism, child abuse, necrophilia, perverted nuns, and several gross of severed penises. Or so Robin Levy concluded after finishing Pop Wasteland (Jon F. Allen and Tim S. Allen, eds. 2015), an anthology of cartoons and poetry, which encompassed all of the above, while leaving him unshaken and unstirred.

He distrusted collections of the previously unpublished anyway, which this was. Unless you paid cash money, or featured celebrated names around whom the less known wished to huddle, which this didn’t, they seemed likely shelters for the cast-off, stunted, misformed. And when you featured forty-four comix, of which forty were a page in length, you were unlikely to have netted artists who’d probed with depth of thought their subjects or themselves. The result came across as spasms of thought, quickly fleshed and spasmodically delivered.

He was uncomfortable with that reaction. He seemed to have become in recent years a “go-to” guy for creators of the unsavory. They seemed to reason, “Well, Levy liked Harry Oddkiss; maybe he’ll like me.” He tried to live up to their expectations. He admired artists who pursued visions more apt to bring them condemnation than more convertible reward. He found satisfaction in the open-mindedness his advocacy for them bestowed. He was flattered by the thought that words of praise attached to his name might advance these artists’ prospects, when this name, attached to his own work, had achieved, oh, not-so-much.

He was uncomfortable with that reaction. He seemed to have become in recent years a “go-to” guy for creators of the unsavory. They seemed to reason, “Well, Levy liked Harry Oddkiss; maybe he’ll like me.” He tried to live up to their expectations. He admired artists who pursued visions more apt to bring them condemnation than more convertible reward. He found satisfaction in the open-mindedness his advocacy for them bestowed. He was flattered by the thought that words of praise attached to his name might advance these artists’ prospects, when this name, attached to his own work, had achieved, oh, not-so-much.

He knew there was an alternate, equally valid view of “Pop Wasteland.” He knew he could say that it voiced courageous dissents and outraged howls against the demoralizing suck of dominant America culture. He knew you could applaud the book, as one advocate for it had told him – shouted actually – as a vehicle for “really taut, cool stuff; not feeble-minded, PC hipster, stick figure, conceptual, poor man’s origami, foldy zine bullshit.”

There, he had said it too, Levy thought. And they could quote him.

Levy had found exceptions to his overall reaction. Aaron Lange’s illustrations had struck him as rich, evocative, and something his eyes were happy to crawl around in. While he generally felt no more comfortable facing up to poetry than he would a Bob Gibson heater, he felt Bonnie Chapman’s “Branching Away” to be slick and spooky. Jon Allen’s cover, a full-color toxic waste dump, built from video games, beer cans, Sylvia Plath poems, and rats larger than superheroes, summed up a world view with originality and wit. And Allen’s “The Ballad of Pussy Riot,” which recounted his censorship on shaky copyright violation grounds by the website Society 6, which removed a poster he was trying to market, engaged him, not least because Allen identified himself as “some broke schmuck” just trying to peddle his art. That had given Levy something besides a severed cock to hang onto.

2.

He was mulling over his failure to grab onto more when Levy read David Golding’s “Doom in the Bud,”

“...I believe,” Golding had written in this dazzling, seemingly renegade Marxist rant, “art’s only function is to humiliate, degrade, distort, and biologize (to the point of abstraction, whereupon we realize there is no biology, only cruelty, and no art, only history.)” That function – instruction through humiliation and degradation – seemed to have been taken up by “Pop Wasteland”; and if Golding was correct, the lesson that there was no art, only cruelty and history, seemed there for the taking. It also seemed, from the placement of “whereupon” within his sentence,” this was a good thing. Was it, Levy wondered, that recognizing life is a struggle, the cruel versus the cruel, would enable people to organize and gird themselves to fight for progress? But when he e-mailed Golding, in Buenos Aires where he resided, he replied that he considered the true effect of biologizing art to be that of eliciting “a dispiriting response in reader/viewer: nausea, pessimism, loathing, all the negative and obscene features of reactionary art.”

That came as a blow. Levy had often flexed his First Amendment-fortified muscles in defense of the (presumably) negative and obscene. When he admitted this, Golding countered that while the transgressive may had value in the mid-twentieth century, “when a liberal-left populist front modernism could justifiably claim to be battling feudal-bourgeois orders,” such shocks now, “both politically and psycho-libidinally... (have become) safely cloistered in the daily ‘private sphere’ of sex and scatology... (as opposed to) something even mildly daring, such as unreservedly taking the side of Palestinian liberation... (or otherwise] challenging the norms... of the ruling psychic paradigms.”

Levy was shaken further. Being called out as a lib-left populist modernist felt like being dumped in the trash bin with the Mugwumps and Whigs. (And the mid-twentieth century had never seemed so long ago.) But he persisted in attempting to fit together what Golding had written, with what the Allens had put between covers. He asked Golding if the person who recognized there was no art, only history, would achieve some valuable understanding. Golding replied that “art... (could be) a strategem or trick (neither bellas nor feas artes) that allows us to get further into a nonartistic, nonmasquerading human consciousness. Kind of like Wittgenstein’s ladder (philosophy) that can be thrown away once it’s gotten you somewhere...”

Levy barely – actually less than “barely” – knew Wittgenstein. He had to look up “feas” in the dictionary. And he wasn’t clear what a “nonartistic, nonmasquerding human consciousness” would perceive; but he felt he was making progress. And his version eliminated unfettered advocation of Palestinian liberation as an endgame.

3.

Levy sat, at 73, four years past the M.I. which had seized him by the scruff and shaken him so thoroughly it seemed to have shaken his thinking into odd and perpeturally shifting corners. (Or had, he considered, the meds which thinned his blood and cleared his arteries also ?) No matter, while he now truly believed each day a blessing, he feared with similar conviction each brought his species closer to extinction. All of geo-politics – the Mid-East, the Balkans, wherever – had come to seem like tribes fighting over dirt; and unless human beings recognized they were one tribe (people), on one plot of dirt (Earth), they were doomed. With that understanding, nations no longer seemed such a good idea. Oh, they had helped transition out of Hobbes’s jungle. They might still throw needed weight against the appetite-driven, raptosaurus-brained herds that roamed the corridors of power. But so long as thought remained state (or family-, tribe-, race-, or even class)-centric, it seemed locked into a planet-demolishing us-against-them mindset.

When he took a long view – figuring a death’s a death, a sorrow’s a sorrow – Levy could argue – despite the inferences of the attention-demanding, large font-headlined wars and plagues – that since life spans were lengthening worldwide and the number of folks tar pit-trapped by extreme poverty was dropping, his species seemed to be getting something right. But at the same time, more rapidly, the beliefs of the Republican presidential candidates notwithstanding, this fossil fuel business seemed to be turning the globe into a shithole.

From this scenic roadside cut-out, his head cranked-up by Golding’s original writing, “Pop Wasteland” began to glow. When Levy’d set it down, he’d wondered why its contents existed. What had these works meant to their creators? Why were they presumed to be of interest to others? What gratification were they expected to bring? Artists didn’t work purely from inner compulsion. No autonomic reaction caused hands to seek pens and pens to gravitate toward paper. Sometimes artists believed, like preachers and pols, they were called to do everyone else a favor. Sometimes, like crossword addicts or masturbators, they sought to test or gratify themselves. Almost always, he posited, they sought to advance interests of their own, secure wealth or fame, enhance self-image or reduce inner tension. But everyone who confronted the empty page, even – perhaps especially – with a chicken-masked corpse-fucker, deserved respect for attempting a potentially useful act. It might be, as his wife Adair told him, each individual must confront society’s paradigms in his own way; and each generation carries within it individuals who, having had this confrontation, may develop new ways – or reveal to others new means – by which to do the important work their times required.

The first generation of UG cartoonists, Crumb, Wilson, etc., had defended their provocations by saying that once they had swept the obvious taboos out of the way, they would be ready for the serious stuff. Levy supposed that had worked to some degree, though the deep cleaning they promised had never materialized. So anyone willing to lift a broom merited welcome, even if the jaded, like himself, had to look at the same-old for a while.

5.

When he thought about it, Golding notwithstanding, there might be no “history” anyway. Physicists and Buddhists had been claiming for a while that time did not exist, the past being merely present memories, the future only present expectations, and there being only a series of co-existing “Now”s. Without time, Levy wondered, how could there be history?

But he needn’t go this far. He need only deconstruct a little. History might be nothing but a totality of events, big and small, from the Fall until the cup of espresso he’d just spilled in his excitement; and any narrative imposed upon them, like the Han Dynasty or World War II, an artificial construct. History was only the sum of all the actions of all the people ever on the planet, lurching around semi-blindly, semi-confused, guided by instinct, impulse and best-available, often seriously flawed wisdom, hopefully in a direction future peoples would find appealing.

To Levy’s as-currently-colonized brain, Jon Allen’s “broke schmuck” remark seemed key to his working through the implications of his understanding. (There had to be some reason, he reasoned, it was the sole sentence he’d quoted on his passage through the book. He just had to find it.) And to do that, for reasons that veered even further from the grasp of explanation, he felt a need to draw from the film “Beasts of No Nation” and the final episode of the UK version of “The Office,” both of which Netflix had flung before him that weekend. “Beasts” was two-plus hours of currently-in-theaters corruption, insanity, murder, and rape, usually carried out upon or by children. It was finely photographed, brilliantly acted, and had left him, wiped, depleted, wondering why he’d watched. He already knew people did terrible things to children and that children did terrible things in return. He did not feel he had gained anything from this refresher course. He felt no more inclined to re-direct his time or re-route his savings to aid infants. He seemed only to harbor increased feelings of hopelessness. He seemed only further deadened to news anchors’ reports.

“The Office,” concerned the workers at a struggling company in a struggling town. The show had run two six-episode seasons (2001-2003), then concluded with a special. The characters were depressed, trapped, thwarted. The central figure was boorish, vain, blind to the indifference or contempt others felt for him. The only two appealing secondary ones were attracted, one-to-another, but, Levy sensed, fated never to connect. Yet this was a comedy, despairing, vicious, subtly played, and dark. And with five minutes to go – maybe, three – the sun shown. Happiness, when it had felt lost forever, burst into the room. Feelings bloomed within Levy he had not suspected he contained. This turn, which stemmed from the show’s treatment of a figure for whom he had felt no better than pity, spread thinly over loathing, seemed to say much about what lay within the human heart.

We’re all broke schmucks, Levy thought. It’s a broke schmuck brotherhood out there, trying to peddle its art since Babylon, in the face of Ghengis Khan and amoebic dysentery, and fuckall. We’ve been drawing on walls 40,000 years. We been making music before that. There had to be a reason. There had to be some benefit. Otherwise, for God’s sake, or Darwin’s, we’d’ve given it up, like our appendix.

Levy recalled reading, a few years earlier in the “Times,” of people assigned to watch a sit-com, a wildlife documentary, or an uplifting “Oprah.” The Oprah-watchers had felt “more optimism about humanity and more desire to help others than the other groups... ” Levy was not advocating removing everything from the dial but the Hallmark Channel. He recognized unleashed artistic ids might remain necessary to clear the ground of inhibitions, impeding progress, like the hedgerows and Dragon Teeth at Normandy. But it suggested that consciousness can be altered toward mankind’s benefit without resorting to LSD in the water supply, which had been one of his earlier positions.

By the time he had reached that sentence, it was nearly Halloween. He had begun with “Pop Wasteland” and moved through Golding, “The Office” and Googling “Does time exist.” There was other stuff too – two volumes of Knausgaard’s “Struggle,” MLB play-offs, Hillary vs. the Benghazi committee, a green-onion-bacon omelette, The Bombadills at Strings, seventy-five rounds on the heavy bag – but for reasons mysterious, his mind had disqualified them from this chain.

On his morning walk to the café where he wrote, pumpkins sat among succulents. Faux cobwebs draped redwood fences. One lawn held faux skulls, tibia, fibula, and hands. The idea was you could be spooked, yet laugh. The hope was you would stroll past the grim into an improved day.

He continued to believe he was getting somewhere. He held the hope we all were.