Steve Lafler is one of those too-late-for-Underground-Comix artists who nevertheless reflected the satirical affect of the 1970s in all its daffy and sometimes dopey energy. Too bad he was only 16 in 1979. On the other hand, he’s a still pretty young fellow practicing his art from Oaxaca, Mexico, in the twenty-first century.

Death in Oaxaca shows the artist at home in that city, among a community of exiles trying to adapt and, if possible, be a force for progress, rather than imposing themselves upon Mexican life, and struggling to come to grips with a culture astonishingly unlike that one north of the border. At least since the time of novelist B. Traven, gringos have been trying to do something similar and the Hollywood Blacklistees fleeing south made a real contribution to the Mexican film industry in the 1950s and '60s.

Lafler’s protagonist-artist has a wife and son to support, but also an urgent need to make music and art. The supernatural is never far away; there are people who transform themselves for adventures, but also a cheerful skeleton and most intriguingly, a geographical memory of Aztec culture a thousand years earlier. The comic may be intriguing because so much of it remains to be unraveled, telling not one story but multiple stories and surrounding that, a vital history and culture to be discovered sympathetically.

Lafler’s protagonist-artist has a wife and son to support, but also an urgent need to make music and art. The supernatural is never far away; there are people who transform themselves for adventures, but also a cheerful skeleton and most intriguingly, a geographical memory of Aztec culture a thousand years earlier. The comic may be intriguing because so much of it remains to be unraveled, telling not one story but multiple stories and surrounding that, a vital history and culture to be discovered sympathetically.

One senses on every page that gringo culture, here and north of the border, is hardly rooted in history or real myth: white Americans in particular have a prepared version of both, altogether too self-serving. We need badly to learn from other cultures to avoid mutual destruction, and time may be running out. Death in Oaxaca is not a reform-minded comic but it tells useful stories and raises important issues.

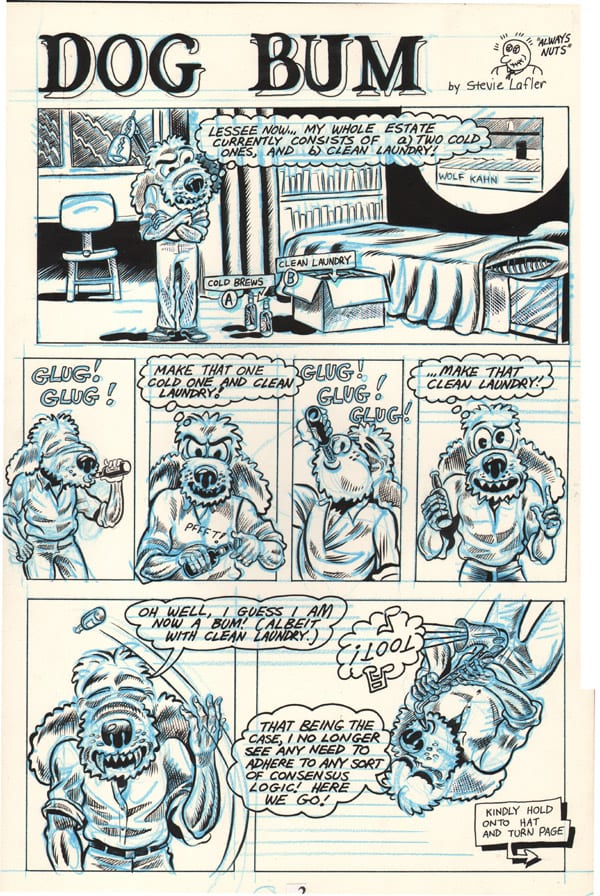

The hefty anthology Doggie Style, a big look back at the artist’s previous work, begins with the indie comics movement of the early 1980s, in the backwash of underground comix’ ignominious collapse. The artist told me that comics-publisher Denis Kitchen told Lafler that he was ten years too late, but at twenty-four, “I was not about to listen to that.” And he wasn’t entirely wrong. When Arcade, the premier anthology, had ended in 1979, Robert Crumb’s Weirdo was nearly starting up, and Art Spiegelman’s RAW was not too far in the future. Lafler, a self-starter, put out as many comics as he could, distributed kindly by Last Gasp among others, and meanwhile pay the rent with t-shirt printing. He was the kind of kid who had worked in co-ops in and after college, including the Amherst, Massachusetts food co-op and an art warehouse co-op in Eugene, and tried to make his own little business a co-op as well.

You could say that he was political without being “political,” that is, quietly skeptical with what passed for the Left, but eager to push eco-politics at the base of popular culture. At Amherst, he had learned the basics from iconic economics prof Samuel Bowles, anyway. Doggie Style has the flavor of over-the-top dopey and sexy humor (Gary Dumm among others were working along the same lines), strange encounters of a half-human with human dames, sometimes skimpily dressed, and an undertone of government/corporate conspiracy real enough during the Reign of Reagan. How to fight the Power? Satire was as good a means as any. And the art is consistently lively, the story lines strong if perhaps repetitive.

The artist says that by the early 1990s, he became a devoted listener to KPFA and got more overtly political. Dogboy (and an “Iron Mike” character who looks like something out of a Justin Green strip) started fighting back against the rich and powerful rather more directly.

Older readers may need to take a toke (perhaps legally!) or just think back to where and who they were 30 years or so ago to appreciate fully what Lafler is laying down. Then again, young folk can look and wonder.