The cartoonist Rénald "Luz" Luzier, a Charlie Hebdo staffer, was born on January 7– the moment for eating a French cake called the 'galette des rois'. This year, Luz spent the evening before it with his analyst. Thinking about his birthday, he told her, made him a little bit blue. Year after year, the day unrolled in a pattern. It started with parental phone calls and finished with a "surprise" dinner.

In between would come the year's first meeting at Charlie Hebdo. To that, being a birthday boy, he had to bring a galette. In 23 years, he grumbled, nothing ever changed. His "special day" was one of hopeless predictability.

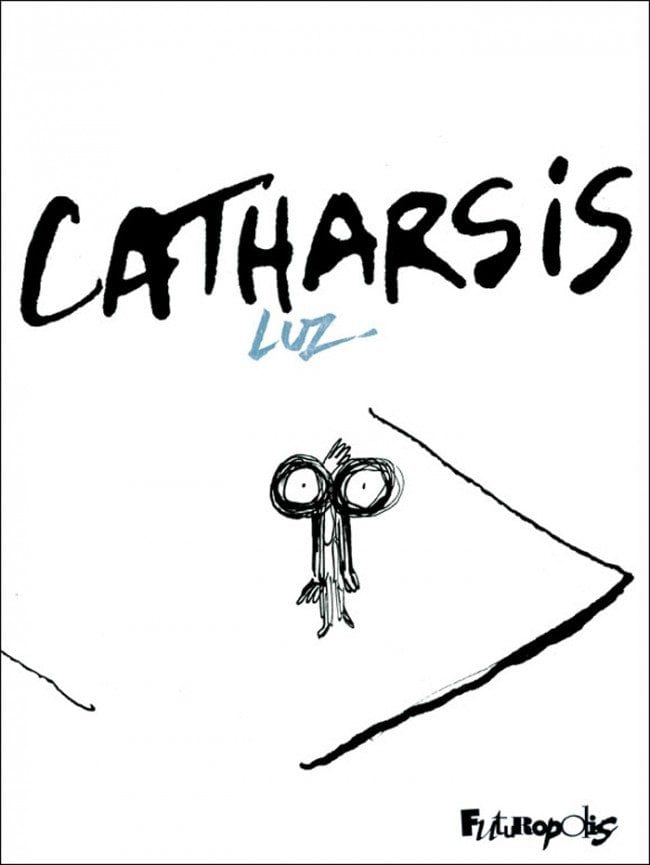

In his new book Catharsis (Futuropolis), Luz recalls this chat. But the memory comes after 114 pages of blood, phantoms, police, guns, media and hallucinations. Frenetic sex alternates with bewilderment and sudden rages flame up before they shrink back into shudders. All this tumult is pictured in different styles, sometimes with anarchic scratches and other times in orderly sequences.

The book is, of course, about how everything changed on Luzier's birthday. But his confessional volume should have a wider interest. That’s because its subtext is the artist’s secret fear of an unforeseen loss of inspiration.

Luz describes it in a little preface. “One day, drawing left me. The same day as a bunch of good friends. The only difference was that the drawing returned, little by little. Both darker and more light-hearted. With this returning ghost, I talked, cried, laughed and screamed… This book is not a testament, even less is it a comic. It’s the reunion of two friends who almost never met again."

The cartoonist had plans to dine well on his birthday, so he slept in until his wife Camille woke him. By the time he set off for Charlie, Luz was an hour late. At its office door, however, a neighbour stopped him entering. Suspicious men, he said, had just gone inside. Clutching his galette, the artist backed away from the door. He heard the volleys of gunshot and saw the Kouachi brothers emerge. Luz watched as they fired into the street where he was sheltering. Once they were out of sight, he ran in and followed their bloody footsteps up to the office.

Having caricatured the news for almost a quarter-century, Luz has announced he will leave Charlie in three months’ time. What unfolded at the paper has made it public property. Yet he is part of that group who have to live inside the story.

It began at a weekly where talent, wit and shouting matches are all givens. But this Charlie, a fourth incarnation of the paper, was a modest world of only 30,000 readers. The journal needed five thousand more to stop it going under.

After the murders, though, time and plans evaporated. Police investigations were followed by psychiatric sessions, then by funeral after funeral. Four days after the attacks came the biggest demonstration seen in France since the Liberation. After that, what remained of Charlie went to work again at a single table in a borrowed office.

Luz drew the cover of their "survivor’s issue". On it, his Mohammed character weeps, a Je Suis Charlie sign offered in his hands. Above him, a strapline reads 'ALL IS FORGIVEN'. Poignant and poetic, it needed no more explanation.

Amidst the genuine sympathy, though, some ugly emotions were brewing. Freedom of expression supported by four million people? Well-wishers of every class, race and belief? That was just a little too good to remain uncontested. In fact, the outpouring had planted some stealthy time bombs, which detonated in sequential polemics. Often these, like much anti-Charlie ink, have shared a certain characteristic stench. It's the odour of compulsive envy, the scent of a criticism that wants less to disagree than simply to spoil or deride.

Nevertheless, judgments piled up around the team at the table. Many came from people who had never read a Charlie, who hadn't seen one for decades, who knew nothing about it other than a couple of covers. Entities from CNN to the Christian Science Monitor delivered verdicts on the journal, on French cartooning, on the history of Gallic humour and on "Muslim life" in France. The disputatious French demographer Emmanuel Todd rushed out a book he called Who is Charlie?. Todd claims that those who marched on January 11 were all "imposters" and "Catholic zombies" who were eager to "spit on the religion of the weak".

All this coincided with the blitz from inside PEN. In speaking for French society and its Muslims, writers like Francine Prose refused to hear anyone else. With her diatribe about "white European" victims, Prose insulted real casualties such as Ahmed Merabet or Charlie’s Mustapha Ourrad. Merabet was himself Muslim and, after decades in France, the erudite Franco-Algerian Ourrad had just been naturalised. Nevertheless, no editor has ever corrected Ms Prose.

Charlie did have its Anglophone supporters. But many of them wanted to make it clear they were only defending freedom of expression. Few really wanted to be seen laughing at Charlie's jokes.

In reality Charlie Hebdo has, if anything, been sharper, further to the Left and funnier than ever. In fifteen issues, ten of its covers have come from Luz. He has caricatured Sarkozy, Hollande and Valls, the Catholic Church, Catherine Deneuve and doping at Roland-Garros. Luz has reported from inside a Romany camp and from the newly-opened Philharmonie de Paris. He picked a battle with the egocentric rapper Booba and has feasted on the war inside Marine Le Pen's family. Luz had lost a lot but not, it seemed, his talent or wit.

Catharsis, however, tells a very different story. Despite all this energy, Luz was running on empty. "Yes, I managed to start again. But I really had to force it. In a sense, I surprised myself. I was telling everyone around me how I couldn’t draw. Yet, the very morning after, I was the first to try."

It didn't prove easy. Luz the DJ found he couldn’t play or listen to music. Luz the artist couldn’t stand to pick up a comic. Art may have been swirling around in his mind, but it was all dark matter: André Franquin’s Idées Noires, the Mitchum books by Blutch, Joe Sacco’s mural of World War I’s worst battle. No longer free to open his shutters at home, Luz lived night and day like an insomniac vampire.

For more than two decades, the drawing he once considered "almost Pavlovian" had been entwined with Charlie Hebdo. But now the paper's every deadline was a torture. Not only was Luz haunted by his lost friends and mentors; he was petrified by the fear of "becoming mediocre".

Catharsis begins where the artist found a light in his tunnel: the simple realisation that, in fact, he never stopped drawing. That, even on the night of January 7, he had doodled mindlessly while talking to police. Much later, Luz realised what he had scribbled, over and over again, was a bug-eyed character Charb often sketched. "I was putting myself in Charb’s place, at the meeting I missed. So I told myself, 'Something is really fucked in your head. But it’s the drawing which will help you understand it'."

Catharsis is a record of how he made this happen. It's jagged, raw and funny stuff that ricochets between opposing moods and moments. Seated next to Charb’s grave, telling Charb about his funeral, Luz has the sudden realisation he's talking to himself. When his wife wears red lipstick, he flashes back to the blood-soaked office. Late one night, in a violent rage, he even stuffs a roll of Charlies into the lit gas cooker. (Camille stops him only by wrestling Luz to the ground).

The cartoonist also has a burning knot in his stomach, a monster that possesses him like the parasite from Alien. He tries to domesticate it with a name, 'Ginette'. "Every time I climb into your heart," Ginette retorts, "I become your unbearable grief…When I go to your head, I'm fear and paranoia…When I sink to the tips of your fingers in order to stop you drawing, I'm your fear of the future mixed with an empty page…also I like to terrify you by slipping into your scrotum…".

A few of the earlier drawings here made it into Charlie. One was a dream in which Luz, missing an eye and half his face, finally makes it into the fatal meeting. In another, he gives his Prophet figure a Rorschach test. A third was an Eros-and-Thanatos strip about making love. But Charlie publisher Gérard Biard found them all too raw, a little too personal for the journal’s bumptious pages. So Luz continued, privately, on his own. He says it was his first time ever doing the work "of a real auteur" in parallel with his day job.

By April, Luz could feel control coming back – and yet something had gone missing from his rapport with the news. After all his struggles, the politics seemed smaller, more trivial. "Drawing had made the dissociation. Drawing showed me there had been a split between that cartoonist of 'before' and the one of 'after'".

Quietly, Luz told the others at Charlie he would be leaving. A month later, in tandem with Catharsis, he went public. He had wanted to keep his departure under wraps all summer. But, shortly after telling some pals, he saw it on the Internet. This is now an irony of daily life at Charlie. On the one hand, fierce security walls its staffers off from the world, making it nigh-impossible for them to go anywhere, meet new contributors or handle the reporting. On the other hand, almost nothing they do or say stays private.

These are human beings who, five months ago, huddled under their desks. Who heard their colleagues die. People who crawled over lifeless bodies in order to phone for help. Now they’re expected to solve every problem in public.

The rumours about their immense riches haven't helped at all. It's been widely printed that donations to Charlie total €30 or €40 million. In fact, around 36,000 people from 84 countries have given the journal a total of €4.3 million. All of it is going to the families of the victims. Charlie’s actual funds come from weekly sales and subscriptions and, since January, these have brought in almost €12 million. Support from the readers, old and new, is very strong. The paper sells 170,000 per week and has 270,000 subscriptions.

Money is far from Charlie’s central issue. On March 31, fifteen of its employees published a manifesto – co-signed by Luz – in Le Monde. It asked, not for dividends, but for an equal say in management. The signatories have proposed making Charlie into a 'Scop', a Société coopérative de production. The idea of such a collective is not favoured by everyone – including publisher Biard, financial director Éric Portheault and editor Laurent ‘Riss’ Sourisseau. Nevertheless, it is going to be discussed in September. That’s when Charlie also hopes to take up new offices.

The journal will benefit from a recent legal change, something Charb was campaigning for at the time of his death. Part of a press reform bill passed on April 2, it's a provision now known as the "Charb Amendment". This created the new tax status of "mutualised media company", open to young, small or struggling publications based around news. Private donors to any of them can now get substantial tax breaks, on contributions up to €1,000.

So far then, it would seem, so good. But, along with Charb’s editorship, Riss inherited all his death threats. Last week, two men were arrested for photographing his home. A messy tiff has also erupted around Zineb El Rhazoui, a Charlie staffer since 2011. Recently El Rhazoui received a management e-mail that, according to who you ask, was either threat to fire her or a "reminder of her duties". Luz says he doesn’t understand how it could happen. "But every person has a different way of dealing with all this. Collectively, it's a staff in post-traumatic shock".

Last week, Charlie’s cover was not drawn by Luz. Instead, 32 year-old Corinne 'Coco' Rey did the honours. One of the paper’s most gifted and versatile cartoonists, ever since the massacre Coco has stepped up to the plate. With talents like those of Riss, Coco and Walter Foolz, the graphic future at Charlie looks plenty exciting. But every fan is hoping that Luz will still contribute.

The week of Luzier's book launch brought the paper a second catharsis. This was the brief office visit from webmaster Simon Fieschi. The most gravely wounded of all Charlie's survivors, 31 year-old Fieschi was shot in the lungs and spinal cord. Like the writer Philippe Lançon, whose face is being rebuilt, he remains in hospital under constant care.

Luz says he chose the title of Catharsis carefully. Like the Prophet, the Charlie carnage is not a subject he plans to revisit. "I expended so much time and so much energy staying strong. I wanted to be there so those people I loved could cry on my shoulders. The book – which is also funny! – is meant as a sort of third shoulder. Hopefully, people will weep on that and I can have my own pair back."