The more scary and depressing the world out the window gets, the more dismaying it feels that the comics of today have pretty much taken a flier on making any kind of serious attempt at political topicality. There’s no doubt that watching the propositions American society’s built on go to pieces invites a yearning for escapism and the trivial, but it seems to me that for our medium to really earn the accolades that the mainstream media’s grown fond of hurling at “graphic novels”, an engagement with the big societal problems of our day and age is necessary. And unfortunately, nobody’s really stepping up to the plate.

The more scary and depressing the world out the window gets, the more dismaying it feels that the comics of today have pretty much taken a flier on making any kind of serious attempt at political topicality. There’s no doubt that watching the propositions American society’s built on go to pieces invites a yearning for escapism and the trivial, but it seems to me that for our medium to really earn the accolades that the mainstream media’s grown fond of hurling at “graphic novels”, an engagement with the big societal problems of our day and age is necessary. And unfortunately, nobody’s really stepping up to the plate.

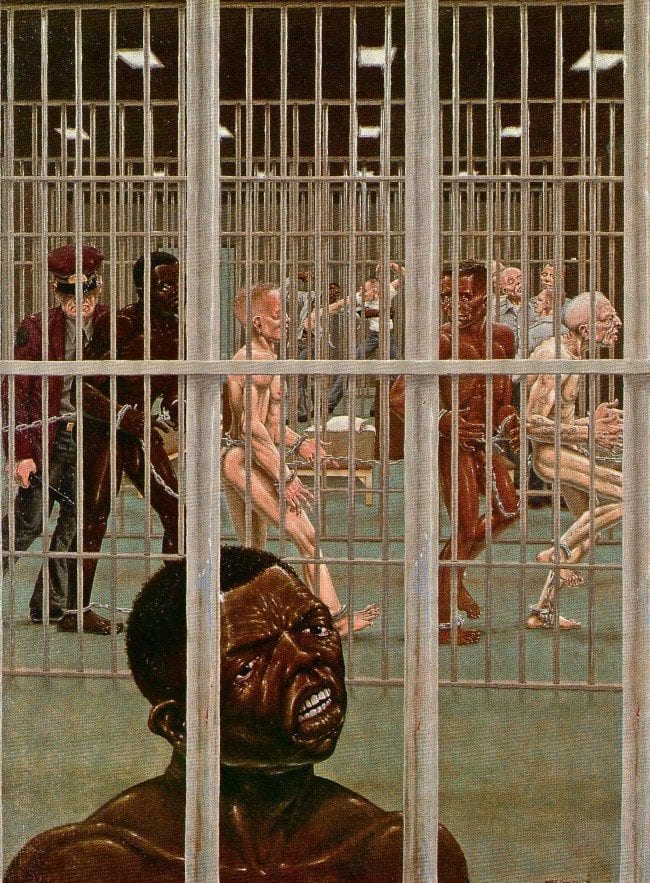

Thank God, then, for Fantagraphics’ new reprinting of Guy Colwell’s Inner City Romance. The most politically cogent of the San Francisco underground comics by leaps and bounds, it’s a book full of messages that resonate as strongly today as they did forty years ago. Colwell’s stories shine an unflinching, brilliant spotlight on the struggles of marginalized and disenfranchised people against the American sociopolitical establishment, picking away at injustices that have only gotten worse in the intervening decades. It’s a little odd that the comic that feels most relevant to 2015 is a rave from the Haight-Ashbury era grave, but so be it: this is essential work, the kind that demands to be seen and reckoned with no matter the time or the place. Inner City Romance has a burning sense of urgency that’s vanishingly rare in the comics medium, one matched pound for pound by the consideration and beauty of every panel Colwell draws, not to mention the near-sublime fervency of the oil paintings the book reprints. If the lack of dust the stories in Inner City Romance have accrued with age is startling, Colwell’s imagery is downright mind-blowing, fluidly cartooned with a rigor and eye for compositional subtleties honed by years of fine-arts training. The second I finished reading the book I knew I had to talk to the man behind it; and since he was gracious enough to pass a few words with me, here they are for you to read

MATT SENECA: What made you leap across the aisle from fine art to comics and begin creating Inner City Romance? What could you do in comics that painting wasn't making available to you?

GUY COLWELL: I think the thing that inspired me to start doing comics after 20 years developing my fine art chops was reading underground comics. I must have first seen Zap in 1967. Before that, comics were comics and fine art was fine art and I saw myself as a fine artist, period. But after Zap (and well, Mad Magazine had its influence) this distinction began to dissolve because I saw these artists doing things that looked like fine art to me, and the stories were daring and invading territory that comics had never gone into before. It did not immediately hit me that I should do a whole comic book, but in early 1968 while I was going through a trial and sentencing for refusing the draft, I began some experiments in sequential panel art just to feel out the medium and see if I liked it. In fact some of the imagery in the acid trip sequence from Inner City Romance #1 was based on these early experimental drawings. I guess the thrust of what I did then was still psychedelic fantasy.

But then I had to go to prison for 18 months. The comic book experiment was put on hold as I continued to focus on small watercolor paintings inspired by the psychedelic experience while I was in the Joint. But there was no acid taking in prison and I gradually got more into looking at reality. My awareness of and inclination toward underground comics was maintained by Spain's Trashman, which I could usually follow because someone had a subscription to the East Village Other which got passed around.

So prison gradually brought out the realist angle in my work. It was a hard, politicizing real life drama that couldn't be escaped in fantasy, but had to be faced and dealt with. And that's the way I began to look at life, the world and political reality... face it and try to do something positive, try to make art that looked at, not away from, what was going on. As I looked at the flow of life around me in the months and years after prison, I sometimes began to feel that individual images like paintings were not always adequate. Sometimes I wanted to tell an ongoing story. That's when I realized only a comic book would work for some of what I wanted to say; and words were needed as well as pictures. So when I wanted to tell a story about the crazy amazing things I was experiencing when I moved to San Francisco in 1971, I finally jumped into comics.

MS: What were your thoughts on comics as a medium when you first decided to work in it?

MS: What were your thoughts on comics as a medium when you first decided to work in it?

GC: The comic medium as a whole? Well, I'm not deeply submerged in the comic thing myself. I used to collect and read the undergrounds but I couldn't devote a lot if resources to this, and I was never very interested in mainstream comics. I mean they are what they are, a medium of entertainment dealing mainly with fantasy. But I wanted to use comics as a medium of social commentary. At least that was the case with Inner City Romance. I can't make the same claim about Doll comics [the 1980s series Colwell followed up Inner City Romance with] which, while still dealing with real life stuff rather than fantasy, were much more of a commercial exercise. But that's the basic difference that runs through my fine art and all my comics; they are about reality, real human concerns not escapist fantasy. This is true of my fine art as well, and this highlights how I am working on the same problems, the same concerns, whether I am drawing a comic book or doing an oil painting. Contemporary reality is my main focus. Even in my surrealist pictures, the elements and issues I put on the canvas are derived from reality.

I think in all of my artwork in whatever medium, I'm trying to bring the viewers' thoughts around to issues of justice, inequality, humanity, environmental stewardship etc. and not offer an escape from the things I think it is vitally important that we work on together.

Of course there are some art writers and aestheticians who preach that any taint of politics makes for bad art. I guess they think art has no other function than decorating walls or offering escapist entertainment. But of course I don't buy this. They would say works like Guernica or everything by Goya or Daumier or Ben Shawn or most of the American realists should be consigned to the category of bad art. To say that art should only be concerned with refined beauty and visual pleasure is to undervalue and disrespect the power of visual imagery to alter consciousness and inspire action. Hey, the cave painters didn't put those animals on the walls just for decoration. They were intended to inspire the hunters to go out and confront the challenge of getting food and securing survival.

MS: Can you elaborate on what the things you felt you were better off saying with comics rather than painting were?

GC: Well, my work in whatever form is concerned with people; the human figure and many aspects of social interaction. I don't have one set of issues that can only be addressed with comics and another with paintings. The media may be different but the issues are the same. A painting admittedly has limitations in that it only captures the external and superficial form of a person. This can tell us lot, but some of the nuances and dynamics of emotion, personality and interconnections between people need an added element of time sequence and language to really dig deep into the human situation. Sequential panel art with word balloons to indicate speech and thought provides some of that depth. So the narrative story line in a comic provides a way to get at ideas that a single image doesn't always have. And I do love to tell stories in the comic panel even if I'm not much of a joke writer. But doing paintings gives me a deep satisfaction in a way that comics can't. As I've said before, if comics are like performing rock and roll then paintings are symphonies, and you can say a hell of a lot with a single picture.

MS: Comics is such a natural refuge for figurative art that it's makes sense you'd end up there. But Inner City Romance also incorporates a lot of abstraction, both in the visuals and the plots, such as they are. What appealed to you about the long dream/hallucination/fantasy sequences in the book?

MS: Comics is such a natural refuge for figurative art that it's makes sense you'd end up there. But Inner City Romance also incorporates a lot of abstraction, both in the visuals and the plots, such as they are. What appealed to you about the long dream/hallucination/fantasy sequences in the book?

GC: Well, down underneath the activist social surrealist there is still a dormant abstract expressionist lurking. For the twenty years I was into fine art painting before prison, I was primarily an abstract painter. I did many purely decorative explorations of form and color and if it had not been for the radicalizing processes of prison, that might have been my life work. It peeks out from time to time in groups of experimental drawings and paintings that usually do not get seen by anyone because the social surrealism is more prominent. The acid trip in Inner City Romance #1 was sort of a last gasp of the old abstract/fantasy vein I was in just before prison, based, as I said, on drawings I did in late ‘67 and early ‘68. Recently I did a series of small abstract oil paintings just because I can't keep this tendency totally suppressed all the time. But, as I expected, this side trip got pushed aside by some new social surrealist painting ideas that took over, such as my new picture of an Ebola treatment center and one I'm working on now of a cute couple with a small child walking through what appears to be violent battle scene.

Of course another aspect of the dream sequences is to explore the inner life of a mind as inspired by the hallucinatory effects of LSD. The trips I took set off a lot of visual experiments because seeing the inner productions of the brain was so incredibly fascinating, colorful and visual that I felt I should attempt to capture some of it in drawings and paintings. There was an explosion of this kind of work in all creative fields in the ‘60's, as you know. Rock posters, rock and roll music, literature and fine art were all hugely moved by the psychedelic experience, just as I was.

MS: In your Central Body book, you talk about your determination to make realistic, figurative paintings despite that not being the cool thing to do in the art world. Do you feel your insistence on telling realistic, politicized stories comes from the same impulse to deal with reality as it is?

GC: Yes, that is exactly right. I'm a painter and a drawer and a storyteller about the reality that I see for myself in the world as it is now. I suppose, as the old bumper sticker says, people tend to feel that Reality Sucks and don't want to see in their comic books and art shows what they know already is happening in the world around them. But I can't help believing it is important to reflect on these things. If we turn away then maybe we do less to address some urgent matters that need remedies. But, well, maybe in time what I'm doing now will be seen as an important historical record.

MS: I'm glad you mentioned that. I think your work does a great job of depicting the feel of a past era, but it also changes a lot with the times between issues. I felt like the arc of the book from beginning to end really crystallizes the changes that took place in both political and also visual culture between the beginning and end of the '70s. Was creating work that looked "current" important to you?

GC: I don't know if I thought about whether the stories looked "current", I just responded to what I thought was important, what moved me personally at the time. But, yes, there was an arc of development and change. Even before the Vietnam War ended, they stopped the draft. Then by 1975 the war itself was over. That certainly cooled things down a lot. The mega-protests ended. Some people by then, as we know, had made the choice to give their lives to revolutionary struggle and we saw a few episodes, such as the S.L.A., which got a bunch of people killed but always seemed a bit more like theater performed for the television cameras than actual revolution. Most people, as you would expect, settled back into "normal" life, no longer espousing or considering joining any uprisings. They started looking again at life as an exercise in love and pleasure and comfort. This change was reflected in my stories, especially #5, which was done while no one was any longer talking about resisting a war or making revolution. But as I saw my comics going more toward pure sex stories with less and less social commentary, that's when I realized I should stop doing Inner City Romance. All the personal, social and international turmoil that brought it into being was over. The stories of sex and self-indulgence in #5 were largely out of sync with the original "soul" of the series so I put it aside

MS: Given that your paintings place so much emphasis on color, it surprises me that you don't have any color comics in print. Did you ever think about or try making any?

MS: Given that your paintings place so much emphasis on color, it surprises me that you don't have any color comics in print. Did you ever think about or try making any?

GC: Well, I made one stab at doing a color comic. It was back between Inner City Romance #2 and #3. I did a 32 page Sci Fi thing called Earth Erectile that fell rather flat. It was all hand painted with gouache, not just filled in line drawings, but a whole book of little paintings. However, the publisher of the Inner City Romance series had no interest in doing this book so it languished for a few years. It did eventually get translated and run in a two-issue serialization in Charlie monthly magazine in Paris, but it did not look very good. (By the way, when that publication was being planned, I was able to work with Wolinski, one of the cartoonists who was gunned down at Charlie Hebdo.) After that, I never tried to do a color comic. I've often wondered if any of my black and white comics might ever get reprinted in color versions, but I can't see myself being the one to do the color. Most likely these days it would be Photoshop or some such software that would be used to add the color, and I hate the prospect of spending months sitting at a computer doing this. If I'm going to be using color, I want to be painting, not keyboarding. Believe me, I know how much work it is to put color on comics as I spent ten years at Rip Off Press doing just that; mostly for the book covers but also many interior pages.

MS: Is there a message to Inner City Romance? If so, do you feel that message is still relevant today? Less so? More so?

GC: I think with Inner City Romance, the messages come on several levels, personal and political. On the personal, autobiographical level, I had to work through the emotional aftermath of being imprisoned, a process that I suppose is still going on now 46 years after I was released. Comics were a great way to do this. I could look at the attitudes I encountered in myself and other inmates. I could look at post-traumatic issues. I could deal with a lot of garbage by looking at it and transforming it in a creative way into something that could both entertain and provoke thought. On the more political level I could reflect on the social and, dare I say, revolutionary events and ideas that were buzzing loudly at the time. Inner city struggles, poverty, activism, protest, war or peace, and the loosening of sexual attitudes were all thrown into the big stew of observations that became Inner City Romance. All this stuff was at a furious boil in the 60's and 70's . Events are not unfolding in exactly the same way today, but many of the issues I dealt with then are still relevant. There is still an epidemic of hard drugs, women are still being turned out as prostitutes, there is more economic inequality than ever, and police are still killing young black men.

But for some reason there is less revolutionary push-back happening, probably because everyone is distracted by the clever little devices they carry around that provide endless instant entertainment and chit chat.

MS: I couldn't agree more that a lot of the problems Inner City Romance confronts are still very much of the now; especially given all that's occurred between civilians and the police in the past year or so. The book feels intensely relevant to me. With that said, (and this is probably even more true of Doll) most of the actions you depict people taking in it are usually either violent or venal, with the kind of grand collective action that acts as a positive counterbalance to the shortcomings of the individual characters never quite succeeding. Do you think the problems you're addressing are eternal ones?

GC: Well, I'm not wise enough to know what "eternal" problems are. But I know that many problems persist and all we can do is try to put some good energy into making things better. I think there are positive, hopeful messages in the pages of my stories, both individual and collective. In ICR #2, James has apparently not taken either of the bad choices that confront him at the end of #1 but gotten to work on positive organizing efforts. The members of the band find the courage to perform for the greater good in spite of the fear that they will be attacked by the police. In #3, the inmates in their brutish and boring situation still have an inner life, which like waking life is full of pleasures and beauty, as well as nightmares. And the apartment dwellers in #4 have a will to overcome their dead-end circumstances and act collectively to pull themselves up. Sure, success is not guaranteed and showing pessimism and cynicism about the possibility of very poor people being able to change things is natural in this unfair world. But throughout these stories, there is an underlying applause for the human spirit and the willingness to at least try.

MS: You mentioned not being much of a joke writer - but I find a lot of moments in your comics funny, even if it's often pretty blackly humorous stuff. Is humor a consideration in these stories? How do you counterbalance it with your seriousness of purpose?

MS: You mentioned not being much of a joke writer - but I find a lot of moments in your comics funny, even if it's often pretty blackly humorous stuff. Is humor a consideration in these stories? How do you counterbalance it with your seriousness of purpose?

GC: Yeah, there's a certain amount of natural humor that bleeds out when writing a sober comic book. But I credit this not to any aptitude for humor that I possess, but more to the unavoidable absurdity of life. I mean, sex is very funny, isn't it? Violence is ridiculous. Much human endeavor and self-absorption is farcical. Cynicism is droll. Hey, it's all a huge tragicomedy and you don't have to try very hard, if you are paying attention to what's going on, to get some good chuckles. So even if I stay firmly focused on the serious purpose, there will always be comedy lurking nearby.

MS: Can you talk a little about how your drawing style progressed while you were drawing Inner City Romance? What was behind switching from brush to pen inking, and the switches in visual tone between issues?

GC: I guess there would be a natural development in style and quality of drawing. After doing a hundred pages or so there would be a bit greater mastery of the craft. Trying different tools and materials also produce different results. I think the most significant choice of tools was the use of a brush instead of a pen in almost all of the first three books. This was my effort to make it a "fine art" effort and keep it more connected to my paintings in some way. But as I went along, I got more into rapid-o-graph pens and then crow quill pens. All of #4 was done with rapid-o-graph, and by #5 I was also using a Tombo Roll Pen Jr., which are no longer made, for a lot of the cross-hatching and stippling. Crow quill and Tombo were my choices when I did all eight of the Doll books and Stacia Stories. I haven't done much comic book work since then, at least nothing that's aroused the interest of any publishers, but I do a lot of ink drawings. Now I almost always use a set of fine archival markers called Pigma Microns. When my book of drawings, Street Scenes comes out soon from Fantagraphics, you'll be able to see what can be done with these great markers.

MS: Can you say a little more about Street Scenes?

GC: Street Scenes is a cousin to Inner City Romance. It will be a limited run portfolio of about 40 ink drawings; the type of item that will be sold directly through the Fantagraphics web site, bookstore or at conventions. All the drawings are unified in subject matter. They are all, as you would expect, city street scenes. A few of the drawings go way back to the 70's. Some are based on old paintings. But most are fairly recent because I've been trying to build up a strong inventory of small works for the exhibitions that are coming up. And, by the way, following up after Street Scenes, there will be a second short run book or portfolio called Disrobed that will feature more than 60 nudes, also mostly done recently for an internet auction site. The drawings in these two productions represent a kind of bridge between comics and fine art and, to me, help support the idea that all of what I do, comics, drawings, paintings, are different aspects of the same big project.

MS: You mentioned exhibitions you have coming up. Can you tell us more about them?

GC: Sure. Since the Inner City Romance collection came out, there has been some encouraging discussions going on about shows. I say encouraging because my work is so controversial, so not soothing or decorative, so outside the comfort zone of most art dealers that it is very hard for me to find show venues. But one situation has been nailed down firmly. In September through November of 2015 I will be showing about 15 large canvas paintings and about 40 framed drawings at a place called the East Bay Media Center in Berkeley during their film festival season. I'm working hard on new paintings and framing for this.

MS: How much do you keep up with what's going on in contemporary comics? Do you have any opinions on the stuff that's going on in the medium these days?

GC: Well, as I've admitted, I'm not deep into comics and can't comment much on what's being done. I kept up with the underground books for awhile, but eventually donated the fairly sizable collection I had to my old art school. If I read comics at all, it tends to be old translated European stuff like Tintin, Asterix or Moebius. The only actual graphic novel I can remember buying was Spain's biography of Che. I know there are some very good, very interesting things to be found within that great mass of work that is mostly super hero fantasy for which I have no interest. There's also an economic factor. I just don't have the money to spend on books. What little I earn goes to paying bills and food and a few art supplies. The time I have available goes to painting and drawing, not reading comics. Most of the reading I do consists of listening to audio books while I paint.

MS: Do you think you'll ever return to publishing comics?

GC: Well, OK, I have started two rather sizable graphic novel projects, neither of which seem to have any prospect of getting into print. I suppose if Inner City Romance and the short run portfolios are so hugely successful that some kind of demand for more from me develops, I will look at finishing these. But I'm not holding my breath. First of all there is In Fox's Forest, a talking animal story which is a kind of personal reflection on prison and its aftermath. I've always thought this one should have color added but that won't happen unless someone wants to publish it and I won't be the one doing the color. It would be about 72 pages long and has an interesting history. I did it while I was working as the assistant manager of a video arcade. To fight off boredom during the hours I was standing around watching people drop their quarters, I would work on it one panel at a time on small pieces of bristol board I could keep in my pocket. A very weird way to do a book, but I actually got it almost completed. The other project was/is a treasure hunt story I call True Treasure, It's about four people walking across a desert and into some mountains in search of a treasure and having lots of philosophical chit chat about life, ideology, the natural world and supernatural speculations. It looks to be about 175 pages long, of which I have penciled 64 pages and inked 32. I've put a preview of it on Tumblr and promoted it in several email blasts. But there has been so little interest or feedback from anyone that I'm not encouraged to believe it would be worth devoting a couple of years to doing. It is unlikely I will start any other comic projects of that scale because I don't like to waste too much of my time doing dead end things that can't be finished. The real demand on my time now is to paint and frame and find exhibitions and I just don't have space for comics.