In celebration of the release of The Comics Journal Library Vol. 9: The Zap Cartoonists book, and the release of The Complete Zap, we present this unpublished interview with the late Spain Rodriguez. It was conducted by Patrick Rosenkranz Sept. 14, 1998, in San Francisco, Calif. It does not appear in the Zap interviews book. All art is by Spain Rodriguez unless otherwise noted.

PATRICK ROSENKRANZ: Would you tell me when you were born and where?

SPAIN RODRIGUEZ: I was born in Buffalo, March 2, 1940.

ROSENKRANZ: Can you tell me the youngest you remember drawing?

SPAIN: I drew in kindergarten. But I remember getting the flash of being able to draw well lying in bed one morning. I had woken up and I still hadn’t opened up my eyes and I could picture how to draw a profile. I was wondering if I would retain it when I woke up completely. So I woke up and drew this profile on the wall. With that, I had this leap of understanding, that I could recreate a face. It gave me confidence. My mother was a painter and pitched me a bunch of clues at various times and helped me solve problems. She was a local painter and had a certain amount of local fame, but never with the big commercial stuff. I was in second grade then, so I must have been 7.

ROSENKRANZ: Did you get into trouble for drawing the profile on the wall?

SPAIN: No, my parents were pretty good about that. I could do whatever I wanted in my room.

ROSENKRANZ: What was the first comic you ever read?

SPAIN: The first comic I ever read was a Plastic Man comic. I remember being intrigued by Woozy Winks, who was Plastic Man’s sidekick, had this outhouse with a propeller on top. I was just intrigued by that idea. I wasn’t really sure what an outhouse was, living in a city with indoor plumbing. I tried to draw it, but I couldn’t quite solve that problem: a flying outhouse. It was just a fragment of a comic the kid upstairs had.

ROSENKRANZ: Where were you in 1963?

SPAIN: In ’63 I was working for Western Electric.

ROSENKRANZ: You’d been there maybe three years by then?

SPAIN: Yeah. I was riding with the Road Vultures. I joined them about 1961.

ROSENKRANZ: You finished art school in 1960?

SPAIN: Yeah.

ROSENKRANZ: You stayed in that job at Western Electric until ’65 or so?

SPAIN: ’65.

ROSENKRANZ: Could you describe some of the things that were important to you in 1963, things you were thinking about?

SPAIN: ’63, let me see. I was interested in political things. I used to go to Socialist Labor Party discussion groups. Mostly working and riding and I always drew a lot.

ROSENKRANZ: Is that during the time you painted murals on apartment walls?

SPAIN: Did I do any then? No, that was around ’65. I did a whole lot in New York.

ROSENKRANZ: You spent the summer of ’65 in New York.

SPAIN: Yeah. My girlfriend was in Long Island.

ROSENKRANZ: That Buffalo Subversive Squad …

SPAIN: That was around ’66. I came back in the autumn of ’65, so all that stuff was going on at the end of ’65 and ’66.

ROSENKRANZ: Who were they, this Buffalo Subversive Squad?

SPAIN: Most towns had a red squad, which basically cracked down on lefties and socialists and communists, anyone they deemed to be politically unacceptable. I think most towns had them. I don’t know about small cities. They had one in Albany. Most cities had them, especially Buffalo. The Buffalo Evening News was one of HUAC’s, the House Un-American Activities Committee’s, main newspapers. They had a whole network of newspapers that would give them favorable publicity. It was a woman who owned it. I remember as a kid during the Korean War, I always thought the Republicans and the Democrats, they were two different parties, but The Buffalo Evening News was vehemently anti-Democratic. Even as a kid it was real obvious. Truman was always portrayed in some utterly villainous way.

ROSENKRANZ: You were drawing for Sunny Daze.

SPAIN: SUNY Daze. Yeah, it was for a newspaper. The name of the strip was SUNY Daze. I can’t remember the name of the guy who wrote it. It was for a newspaper up at the University of Buffalo.

ROSENKRANZ: But you weren’t a student there.

SPAIN: No, I wasn’t. It was for a little newspaper called The Spectrum. It got taken over by a left-wing group. The first strip I had done, SUNY Daze was a student who was going through this world of the mid-’60s with all these events happening and he was sort of in a daze. SUNY being State University of New York at Buffalo. I wish I could remember that guy’s name. [Jeremy Taylor.]

ROSENKRANZ: He wrote it, you drew it.

SPAIN: Yeah. At that point I got some understanding of how much actual work it was to do a whole strip like that, crank it out every week, or every other week. I can’t remember how often it came out. It was a long strip, maybe three or four panels. Sometimes it was half a page.

ROSENKRANZ: That was your first published work?

SPAIN: I had done stuff for The Militant, which is a Trotskyist newspaper. Before that I had worked with a guy named Ed Wolkenstein in Buffalo, and we put out a thing called The Spirit and the Sword, which was mimeographed. There was a whole bunch of issues we put out. This was the first time I learned about John Brown. The guy was originally a high-school history teacher, and worked in a steel mill. That was around the time of the Goldwater election.

ROSENKRANZ: Was it an adventure strip?

SPAIN: No, that was definitely political. I didn’t do any strips. I did illustrations. Then later on I did stuff for The Militant, in fact that summer of ’65 when I went to New York. “The Spirit and the Sword” was a quotation from John Brown. It was mostly text. It was mimeographed.

ROSENKRANZ: You had to draw on those stencils?

SPAIN: Yeah, that was it: draw on those stencils. You’d draw a negative and then see how it came out as a positive.

DISCOVERING THE UNDERGROUND PRESS

ROSENKRANZ: When did you realize there was such a thing as an underground press?

SPAIN: It was The Militant, which was a Trotskyite newspaper, which had been around. You could also pick up The Weekly People, which was on a lot of the corner sidewalk newsstands, which is the newspaper of the Socialist Labor Party, a real old party, a pre-Marxist Party that comes out of the 1800s. The layout of the newspaper was always great, because you could always get into an argument with somebody. The newspaper was about this big and with those big block letters and the arm and hammer, which is some association with Armand Hammer’s father, who was a socialist. There was a connection between that Arm & Hammer logo and the Socialist Labor Party, which is from the turn of the century. They had this great logo. You’d just sit over there with the newspaper and somebody would give you an argument about it.

ROSENKRANZ: Did you consider that an underground paper?

SPAIN: It was an alternative paper. It wasn’t really underground. The first underground newspaper in Buffalo, we did. We put out something called Pith. The guy who really got it together worked at some silkscreen place. It was a silkscreen newspaper that we put out that had all this wacky stuff in it. I don’t know where he got the title. It was a pithy title. He was a strange guy. A story that says everything about him is: One time he was going to New York. He was a strange-looking guy, even by today’s standards. He looked a little like Orson Welles. He had a beard and had loud rose-colored glasses and would wear this hat. It was a New Year’s hat and it was spray-painted black, with an Italian flag sticking up. He wasn’t Italian. He was a big guy. He had this sweater that hadn’t been washed in a long time and it had these little beads on it: these pants that came up to here and sandals.

Some guy like that, especially in 1965, would attract a lot of cop attention. It was about four o’clock in the morning we’re going through or around Schenectady, where the cops were known for being nasty. The cop pulls us over and sees him and … Hey, man! The head guys from every police department around there. Here would come the state cops and different cops. He had this way of talking. He would say this strange stuff but in a conversational tone. They started talking to him and he was saying all this weird stuff and after a while they just start walking away. He was the editor of Pith. His name was Gary Stevens. Unfortunately, he committed suicide. They entrapped him in some drug bust and he was facing time. The sad thing, in Buffalo — I wasn’t there at the time — I think if they had gotten enough community support behind him, they might have helped him to stave off that kind of depression about the jail time. Or brought him out here. He killed himself. He was a real strange guy.

ROSENKRANZ: I used to read EVO [The East Village Other] all the time. Where was their office and what did it look like?

SPAIN: The first office was on Avenue A at Ninth Street. It was a real small place, a storefront with two rooms, a front room and a back room.

ROSENKRANZ: The front room was where they distributed papers and the back room was where the production work went on?

SPAIN: Basically. Then they moved upstairs of the Fillmore East, which was on Second Avenue and 6th Street.

ROSENKRANZ: Can you tell me about the editorial staff and the people who worked there?

SPAIN: Yeah, Yakov Cohen, he was a good guy, and Walter Bowart, whose daughter lives right down the street. Yeah, I was walking to the store for a quart of milk and there he was, standing there.

ROSENKRANZ: You weren’t real friendly with him.

SPAIN: We didn’t part on the best of terms, but it was good to see him. We sat around and bullshitted for a while. I got to send him that interview (about the bathroom mural). It was too bad because we could have done something good. But he was determined to boot us all out.

ROSENKRANZ: What about the rest of the staff.

SPAIN: There was Allen Katzman, Jaakov Kohn, Peter Leggieri, Joel Fabricant and me, Kim [Deitch] and Peter Mikalajunas, who was the art director. We were the three guys in the back room. We were the guys who put out the newspaper. Later on Don Lewis and various writers. Dean Latimer, he was another guy.

ROSENKRANZ: And that guy who liked to go through people’s garbage.

SPAIN: A. J. Weberman. He has a website.

ROSENKRANZ: Kim [Deitch] has told me stories about the apartment you lived in with the hole in the wall.

SPAIN: Yeah, they kicked a hole in the wall. Gary Stevens visited our apartment for a while. Unfortunately, he took down the door to our apartment at one point. He was the guy who did that. For some length of time, I would be sitting there with a pound of grass that I was in the process of selling with the door sitting up on its hinges. I eventually was able to get it back in. We had no landlord. We hadn’t paid any rent for a long time and the landlord wasn’t coming in to fix anything. It was OK when we had a family living next door, but they had a fire and they moved out and the junkies kicked a hole in the wall.

ROSENKRANZ: It was no wonder you were able to live so cheap. You didn’t pay rent.

SPAIN: Yeah, right. Really.

ROSENKRANZ: When Crumb came to town, he stayed with you?

SPAIN: The first time he came to town, he stayed with these friends of ours, Betsy and William. When he was staying there, I might have even been living downstairs.

ROSENKRANZ: Bodé is one I never met. You described him as being pretty conservative when you met him.

SPAIN: Yeah, he was really intrigued by all this stuff that was going on. When I ran into him again years later, he looked completely different. He had hair down to his shoulders and one long fingernail painted green and eye shadow and all that.

ROSENKRANZ: What was that Cartoon Guru stuff about?

SPAIN: I don’t know. He had really mastered that Pop Guru rap. When we first met him, his stuff was brilliant. He had all this stuff laid out, this whole world laid out. Nice stuff. He was from Rochester. I had an interesting experience in Schenectady, when I was on my way to New York for the first time. [I was] riding my bike, and it was about six o’clock in the morning and I was crossing a bridge. This hot rod came up and one guy had a bottle of beer or a bottle of something and offered me some. We went over to some diner and sat around and bullshitted for a while, and then took off.

BUSTED

ROSENKRANZ: Can you tell me about the bust of Kiss magazine? Isn’t that the one where they cited that story of yours …

SPAIN: I thought that was in EVO. That was earlier. I don’t think that strip was in Kiss. Before I was doing Trashman, I was doing this amorphous strip, whatever would come into my head. I had this one character. He was giving this woman head. They busted the guy who sold the newspaper, so the next week I had him punching her out and the newspaper wasn’t busted.

ROSENKRANZ: You were never called to testify.

SPAIN: No, they busted some old guy who was peddling newspapers.

ROSENKRANZ: That had no effect at all on the publication?

SPAIN: No. It kicked up a certain amount of publicity for a while. Increased sales. I ran into one of those guys who edited Gay Power, I forget his name. They used to have a Midnight Dream Show at the Palace. The name was changed to the Palace from the Pagoda. I think now it’s a restaurant. They had this Midnight Dream Show, which was pretty interesting, put out by all these gay guys who had a lot of interesting underground and offbeat movies and shows. All these guys would come out in drag. This guy comes out and he’s all done up. He has a beard with spangles and lipstick and eyelashes, and goes, “Oh, Spain.” And it’s this guy. At first it was weird talking to this guy, but after a while I realized that somebody seeing it from the outside would think it was bizarre because I was talking to somebody in unusual garb, but it was just two guys talking. He was the editor of Gay Power.

ROSENKRANZ: Did they produce it out of the same office?

SPAIN: Yeah.

ROSENKRANZ: That must have gotten pretty crowded.

SPAIN: Yeah, but it was never a problem. People were always in and out. When we would put out the newspaper, we would put it out in the back room. The thing that really intrigued me about New York was that you could go there and get all these great publications like The Realist, Socialist papers.

ROSENKRANZ: You said in 1969 that you came out to San Francisco around the beginning of the year. You said in an interview a friend called you and offered to come get you. Now that wasn’t the Lark Clark trip, right? That was before?

SPAIN: That was a different trip before that. He came out. I remember I thought no one was going to come cross-country to get me.

ROSENKRANZ: You did two trips in the winter: one in January and one in December?

SPAIN: Yeah, the one in January we came up through New Mexico.

ROSENKRANZ: Was that someone involved in comics?

SPAIN: No, just a crazy guy.

ROSENKRANZ: EVO was afraid of losing you, so they gave you an airline ticket to come back?

SPAIN: Yeah, they said if we buy you an airline ticket, will you come back? I said sure, man. I’d never flown cross-country before. I didn’t leave because I felt any dissatisfaction with EVO. It seemed like a neat thing to do. I’d never been out here before. The guy did come all the way across the country to get me.

ROSENKRANZ: What were your first impressions of the underground comix scene?

SPAIN: Great. Things were really bubbling. I met [S. Clay] Wilson for the first time. I stayed with Crumb. It was ’69, so the Summer of Love had happened a few years ago. You could go out in the Golden Gate Park and some guy would offer you a joint. The hippy ambiance was still there. Now it’s transformed, the hippy has a somewhat nastier edge to it. You could see pimps out there. When I first came to San Francisco and I was hitchhiking around, when I would tell people that I was living in the Haight, they’d say oh, it’s so dirty and dangerous out there. You know.

ROSENKRANZ: You were from New York.

SPAIN: Yeah, right. It looked pretty clean and safe to me.

ROSENKRANZ: I want to ask you about the Zap #4 art show at the Phoenix Gallery in Berkeley.

SPAIN: I probably wasn’t here at the time. I’d gone back to New York already.

ROSENKRANZ: Was that the first time an art gallery had paid attention to underground comix?

SPAIN: At some point there was a show in New York at the Whitney Museum and they used some of my stuff. I think that was the same year.

ROSENKRANZ: What do you think were some of the best underground comix?

SPAIN: There was a great one called Two-Fisted Zombies. Skull. Insect Fear and Mean Bitch Thrills.

ROSENKRANZ: What about the biggest dogs? How about Dave Geiser?

SPAIN: Me and Dave Geiser almost got into it. Gary Arlington was putting out a bunch of EC covers that other people would do.

ROSENKRANZ: That Nickel Library series?

SPAIN: Yeah. One time I told Dave Geiser he wasn’t good enough to be an EC artist.

ROSENKRANZ: He was convinced he was great.

SPAIN: He still is convinced that he’s great. Last time I ran into him was down by Big Sur. He was marrying some good-looking woman.

ROSENKRANZ: I met him in Paris in 1976. He was staying with Willem.

SPAIN: When I was breaking up with my first. We were in the middle of a real nasty fight, when [S. Clay] Wilson called me up. Him and Geiser were in some bar that was down at the end of the alley in North Beach where I lived. So I went down there and I was sitting between the two of them while they’re both arguing over who makes the most money.

ROSENKRANZ: How does Geiser make any money from his comics?

SPAIN: He does painting. He claims he does well at it. He’s a nice enough guy. I just always hated his work. All this stuff came out and I didn’t even read all of it that came out of the woodwork. There was tons of stuff. It seemed for a while that anybody could get stuff published. The market became oversaturated.

PEAKED

ROSENKRANZ: What were the signs to you that it had peaked?

SPAIN: At some point, they tried to make that leap into Arcade. The thing that was really a kick in the ass to underground comix was when they closed down all the head shops. The fact that you had underground comix in there was taken as evidence that you were dealing drug paraphernalia. It didn’t end right away. It just slowly went down. It never died. Later on, we were all trying to find any other kind of work that we could. Justin [Green] becoming a sign painter was certainly a strong indication. I was fortunate to do stuff in Zap and various things. I was able to hang on for longer than most. Certain people would drop out like Jay Kinney, who did good work.

With the crumbling of Arcade — that was certainly an indication that an era had passed. I had an idea for a comic called Stomp: The No Nonsense Comic. When I first got here you could get just about anything published. With that, I had difficulty getting people to do work for it. I probably could have found someone to publish it. But, slowly, it became more apparent that underground comix weren’t selling as much as they had been. You hang on with one thing or another. Doing comix is labor intensive. There was a lot of good stuff that came out. There was all that crap. Zap seemed to be the one place that was consistent. The artists did good stuff. But the royalty checks slowly started petering out. You were getting them every month, for a long time, into the late ’70s. Then you start getting them less frequently, or you get 40 bucks a month. If you had a cheap place to live, you could survive and have a good time.

ROSENKRANZ: Robert Williams said Print Mint was cheating you guys and so you switched to Last Gasp.

SPAIN: One of the things they had done was stolen one of the jams and sold it to somebody, the original artwork. Someone got a good deal. We’re trying to get 7 grand for the latest one. At that point, they were on the ropes. Bob Rita was into junk.

ROSENKRANZ: Williams said sales were high but the money wasn’t trickling down.

SPAIN: The whole problem, the ongoing problem, is keeping track of what’s going on. The good thing about Zap, through the initiative of Victor Moscoso, is that we owned the negs. [Ed. note: Original artwork, at that time, was photographed, using a large camera — aka. photostat machine— that generated a film negative that could be used for print-quality reproduction.] That was one of the issues we had with the Print Mint. So we own the negs and whenever Ron wants to print them, he has to get the negs from us, so we know he can’t print any more than we know he’s printing. The long history of problems for artists is that they don’t have business courses in art school. You have to learn all this stuff by trial and error.

So we’re still in the process of figuring out what procedure we should have to keep on top of the business aspects. It’s been an evolutionary thing. We had the Cartoonists Union and one of the good things with that is we had a lawyer come in and give us a talk on how we should protect our copyrights. At one point, Last Gasp wanted the Wimmen’s Comix group to sign all their rights over to them. We warned them about that. The tendency in any operation is for it to fall apart, for it to become looser, and people forget things. Business-wise, we’re trying to develop a procedure that when anybody gets paid, everybody gets called up so everybody knows they have money coming. Ultimately, we have to look after our own interests. If we leave it up to the publisher, they might forget.

ROSENKRANZ: Did the Zap collective have formal meetings?

SPAIN: It was fairly informal. We didn’t have scheduled meetings. The way putting out a comic works is somebody does the cover. They are the ones who have the biggest incentive to get the comic finished. Usually they bug everybody. In my experience, I would bug everybody and people would say, yeah, yeah. After a while you get tired of bugging everybody. Williams would usually get his stuff done first. And I would be a close second, and Crumb would get his stuff done. Moscoso and Rick [Griffin] would be the last guys to get their stuff done. It would seem like nothing was getting done for years and then suddenly everyone would say, isn’t there going to be another Zap? It would happen real spontaneously.

ROSENKRANZ: Will there will be another Zap, with or without Crumb?

SPAIN: Yes, with or without Crumb. It’s just too good of a deal. First of all, the name Zap sells. We have a good deal with [Ron] Turner. What I said is: if nobody wants to do Zap, I’ll do a Zap myself. Why not?

ROSENKRANZ: I noticed you gave Crumb a hard time, but nothing was said about Shelton or Williams.

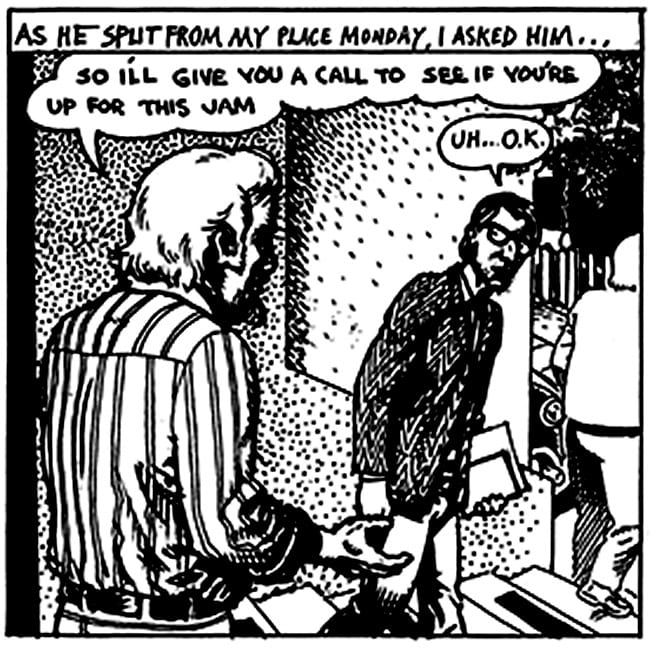

SPAIN: It was stated in the strip that our beef with Crumb was he just didn’t treat us right. If he had called us up. I spoke to him. I called him up a few times. He wasn’t there. He knows how to get a hold of me. When he left here, I said I’ll call you up to see if you want to be in this jam. Give me a call. I didn’t want to pester the guy. He just never called me up. If he called me up and said I don’t want to be in the jam, and if we’d gone over there we would have had coming whatever he wanted to give us, but what did we know? The thing is, this is the way he always is: “I don’t want to be in Zap.” “I don’t want to be in Zap.” Then he turns out something great. We all get together and have a great time. Granted that Moscoso slapping him in the elbow. That was the big punch-out. Even as we speak, guys are getting their asses kicked. A cartoonist gets a slap in the elbow and we never hear the end of it.

ROSENKRANZ: Was adding Mavrides a last-minute decision?

SPAIN: Part of the conflict is that Crumb always wanted to open it up to the new guys. When Crumb had set it up, it was a combination of an act of generosity and Crumb just not wanting to bother with it. It wasn’t quite clear how it should have been set up. If it was set up in a way where if you weren’t in Zap you would lose your voting right, that would have been an incentive for everybody to be in it, and also it would have been a way to eliminate Moscoso’s veto power. This is a contention between Crumb and Moscoso. The only editorial consistency is that we have these same guys in it all the time. I personally never had any objection to anyone new. Wilson did mostly. I don’t know if Williams did.

ROSENKRANZ: Williams said to me, “Don’t blame it all on Wilson. I felt the same way.”

SPAIN: Those were the guys. They didn’t want anybody new in. Then with Crumb leaving, I think bringing Mavrides in was kind of a belated attempt to appease Crumb, and we needed another artist. All kinds of stuff could have been done. There were all kinds of suggestions. I wanted to bring [Stanley] Mouse in. You could just have guys in for one issue or something.

ROSENKRANZ: What do you think about that line Mavrides gave you about Rick?

SPAIN: That was funny. To be totally accurate, when Rick died, he had returned to Zap. It’s just that it took him 30 years to turn out a strip, to turn out a page. When we all worked on that last jam, the first time we got together, everybody was working their asses off and Rick was talking on the phone to his girlfriend. Then the next time we got together, he brought in his panel and it looked beautiful. All through the thing, everybody’s working away, including Rick, and we look at what he had done. It was the same panel, but at that point he had an eighth of an inch of Wite-Out and ink. He just kept changing it, the panel. He was just this guy who was completely at the mercy of the muse.

(Continued)