Gabe Fowler’s comic-book shop, Desert Island, stands unassumingly on Metropolitan Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Fowler has chosen not to take down the original bakery sign in front of the shop, partially obscuring his wares to passersby who don’t know any better. Inside is an oasis of self-published comics, small-press titles, graphic novels, and original art. Fowler does not turn down consignment from artists, but it’s clear that most of his titles are carefully chosen. He even publishes a newspaper called Smoke Signal, which features many of today’s best cartoonists contributing original content for the publication. Fowler has just collaborated with Nobrow Press on the most recent issue, giving each page a splash of Nobrow’s characteristic aesthetic: bold and beautiful color work. Fowler is clearly proud of this accomplishment.

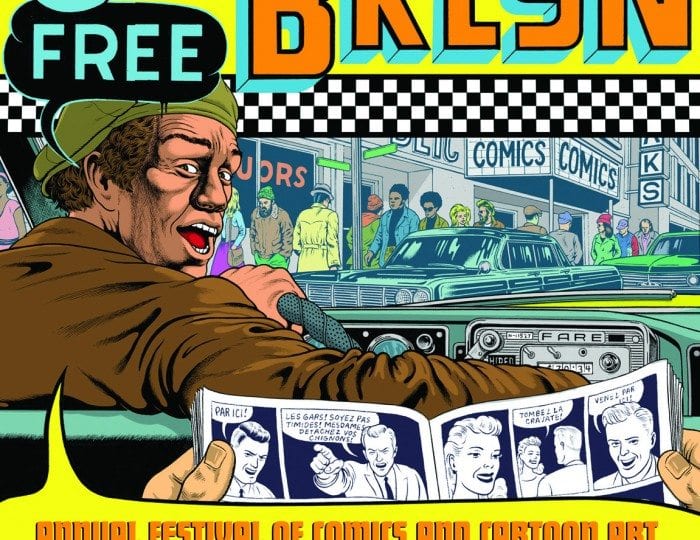

After opening Desert Island in 2008, Fowler noticed that people were starting to complain about the annual MoCCA festival's prices and management. At the time MoCCA was the only major small-press comics show in New York City. “I couldn’t believe people were paying so much for table space at that show," says Fowler. "And the show was charging $15 admission to the public. It seemed like a broken system.” As a result, Fowler decided to start a small show in Brooklyn with a more focused aesthetic, cheaper table prices, and no admission charge to the public. Worried about his ability to attract artists as a newcomer to the industry, he asked Dan Nadel (one of this site's editors) if he wanted to start a show with him. Nadel immediately agreed and proposed the name Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival. Dan then asked Bill Kartalopoulos to run the programming. After a four-year run, Nadel and Kartalopoulos dissolved the show, and Fowler launched a new convention using the same model, with a new name: Comics Arts Brooklyn. He asked Paul Karasik to coordinate programming.

It’s clear that Fowler’s eye for thoughtful curation translates from his store and into the festival. Getting accepted into this show is a coveted position for many indie cartoonists, especially those in the greater New York area. It’s a relatively small show, this year around 100 tables, in a geographic location ripe for sales given its demographic of young, artsy types with purchasing power. The Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Church is a somewhat intimate setting, neither overwhelming nor difficult to navigate. Over the years, the show has consistently been reported as being well-attended with a steady stream of customers throughout the day.

“Festivals add a much needed element of humanity to an increasingly inhuman and digital world,” says Fowler. “For me, the most important aspect of conventions is facilitating artists and fans meeting each other and hanging out. But as a fest organizer, it's important that exhibitors do well financially. Obviously I can't force that to happen, but I can try to make an ideal environment for sales and exposure for artists and publishers. My methods for attempting this are: organizing the show with an eye on innovative content and production, keeping the books sales aspect free to the public, and promoting the show as much as possible.”

It’s true that not all shows are created equal when it comes to sales opportunities for exhibitors. Although many at this year's show noted that CAB was not as well attended as in previous years, and that their sales suffered as a result, the show has still developed a reputation as a lucrative show for many. The reality is that distribution remains an issue for individual artists, as well as many small publishers. There is no small press equivalent to Diamond, but instead an ever-evolving roster of smaller distributors with their own policies for accepting comics. Furthermore, many individual artists forgo outside distribution, selling comics in their own online stores or at conventions.

For those looking to get their work into stores, perhaps the most prominent person in this field is Tony Shenton, a sales representative who represents a comprehensive swath of indie comics creators and publishers. Shenton started repping back in 1993. “After I was laid off from my job as a comic shop manager in the first Bush recession," Shenton explains, "Terry Nantier at NBM Publishing, from whom I had ordered in my prior position, answered an 'employment wanted' ad I placed. He said, 'I have a crazy idea,' which was to apply the bookstore rep model to comic shops. After a while, another opportunity presented itself when another comic shop manager told me he was going to change careers and publish comics and graphic novels full time. The proverbial light bulb was lit above my head. I was freelance, after all, so I said to Tom Devlin, then of nascent Highwater Books, 'I could be as politely persistent for you as I am for NBM.' He eventually agreed, and started to suggest my service to his publishing friends. It grew like the Blob.”

When Diamond Comic Distributors Inc., the largest comic North American comics direct market distributor, raised its minimum orders from $1500 to $2500 in 2009, it was expected to be a death knell for small publishers who were reliant on the company for distributing their catalog. But to Diamond, a company designed to cater to bigger, more mainstream publishers, catering to the needs of many small-press operations appeared to be incompatible with its operation. Looking back, Shenton sees the practicality of the policy changes, especially in a difficult economy. “First, let me say that the service Diamond offers is essential," he says. "There is no one else ready to spring from Zeus's forehead and take over distribution to every comic shop in creation. They are the 2000-pound canary. However, their business needs to be profitable. They had to take a hard look at what sort of minimum made a listing of a new comic worthwhile to handle. For many who were involved, that minimum excluded them.”

Interestingly, it may have been this policy change which saved Shenton’s operation. “The service I offer received more inquiries after that announcement," he says. "That wasn't a surprise, considering how many small presses were affected. In retrospect, since things were still getting worse at that time, Diamond's policy shift quite possibly kept me in business fighting for this branch of the comics industry.” Ultimately, Shenton believes that Diamond’s decision actually benefited the small press market in unexpected ways, “forcing creators to use their imaginations and time to use other services - or establish them - to get their books out.”

After CAB, I followed up with some exhibitors to gauge their experiences and gain some greater insights on what shows like this mean to them, in the context of distribution and sustainability. Kevin Czapiewski is a cartoonist and relatively new micropublisher/distributor (Czap Books). This was his first time exhibiting at CAB, although he’s attended before. He mentioned that sales were not as profitable as he had anticipated, but that he had a great experience with the show overall. “Shows like these are really the core of my sales, both as an artist and a publisher," he says. "I get a steady flurry of online sales, but the shows are where it comes together. Sales, promotion, networking, life support, the whole deal.” Czapiewski mentioned that “hand-selling” continues to be his most successful means of distribution. “I've been doing this just long enough that the question of distribution and marketing is really starting to be a nagging one, but some people are starting to take baby steps into the playing field. Neil Brideau's Radiator Comics, Robyn Chapman's The Tiny Report, and Jared Smith's Small Press Previews come to mind. A lot of people are thinking hard about this.”

I talked to Robyn Chapman, cartoonist and micro-publisher (Paper Rocket Minicomics), about The Tiny Report. The idea grew out of her interest in minicomics history and her growing awareness of the proliferation of micro-presses, which see sees as a “movement.” She agrees with Czapiewski in many respects. “I think conventions are very important," she says. "One of my biggest challenges as a micro-publisher is distributing my books. There are very few distribution options available to me, so I'll use anything that works. And what works for me right now are conventions, Kickstarter, and selling through Desert Island. (Because I work there, I can always keep my books in stock).”

However, Chapman goes on to note that it has grown harder for her to turn a profit at conventions or simply break even. “I believe I'm producing the best work of my life, but selling comics at conventions was easier when I was in my early twenties, when my work was often, in my opinion, mediocre. I think there are a few reasons for this," Chapman says. "The number of quality small-press comics being produced has increased, but the audience hasn't grown at the same rate. It's harder for work to get noticed.”

Conventions like CAB are “very” important to Chris Pitzer’s publishing company Adhouse Books, whose mid-size business gives it an unusual position. Exhibiting at conventions allows Pitzer to discover new work and talent as well as catch up with other publishers. He does note though that Adhouses’s biggest distribution channel is Diamond. “They distribute to both the book and comics [direct] market for us," he says. "While it is advantageous in some regards (Amazon, B&T, etc.) there are definitely challenges. We’re kind of stuck in the middle of being 'alternative' but not too artsy. We also get help from Spit & a Half. John [Porcellino] can move some units!” Adhouse’s “middle” position adds a further challenge. “It’s tough to have your work heard above the 'shouting' at the front of the [Diamond] catalog. But… we’ve been doing this for over ten years, so I think we’ve built a reputation or 'brand.'"

Annie Koyama of Koyama Press, explains that as a Canadian publisher, travel costs are a significant factor in her United States convention sales, making it tricky for her to determine which sales method (conventions, online, stores) is most profitable. Reflecting on how the circuit has evolved since she started publishing, Koyama says, "The sheer number of new shows that have begun since 2007 is pretty impressive. Some are great comic towns, but if the sales don't reflect that population, I think that some of those shows may become important regional shows but attract fewer international publishers." Given Koyama's diverse offerings, she is cognizant that different shows attract different crowds, which may, for instance, account for better sales of art comics versus kids' comics. Fundamentally, Koyama derives satisfaction from helping to introduce artists to the people who are buying their work.

Adhouse Books and Koyama Press are mid-size indie publishers; just how important are convention sales for a larger publisher like Fantagraphics, compared to online and store sales? "Apples and oranges," says Eric Reynolds, associate publisher of Fantagraphics. In a world where books are available to purchase online, conventions serve other purposes, which are still important to book promotion and ultimately sales. "I would say that we do shows for two reasons," says Reynolds. "Because the mission of the show is simpatico with our own goals, which means that it's a viable show to promote our authors and new books at, and/or because we think we can make some money (or at worst not lose any)."

Shenton is often seen frequenting shows like this, catching up with artists and publishers he represents, collecting samples of their new work, and scouting out potential future clients to work with. “Only a minority of comic shops will order small press, so conventions help raise awareness and appreciation for these off-the-beaten-track comics,” he says. “While some shops use these shows as an excuse not to order, consumers can still be leery of buying through the Internet. These fairs let them handle and inspect the books with less pressure.” Shenton then reiterates, “Income is essential, and these shows can provide ready income for the publishers who attend. Networking among publishers can help creators find more assignments, or allow them to pitch projects if they want to move away from self-publishing. Today's minicomics creator may be tomorrow's best selling graphic novelist.”

Sustainability is a word that I hear floating around the small-press comics world. This is an industry people choose to get into primarily because they love the medium of comics, not because of the money, but that doesn't mean that financial concerns aren't real, albeit complicated and often frustrating. “Art and commerce is always a troubled combination,” says Fowler. “It's a contradiction. I'm an idealist, and I like to see artists making work apart from considerations of the marketplace, but I'm involved in a commercial enterprise related to the sale of artwork. These issues are larger than comics, but they're predicated by living under the dominant economic model of capitalism. Artists shouldn't think about commerce when they're making work, but in America people vote with their pocketbooks, and it feels good when a stranger gives you money for your art. It's important.”

Leah Wishnia, the NYC-based artist and publisher/editor of Happiness Comix, acknowledged that shows like this are “good for sales,” but that she mainly goes to shows to connect with comics folks in person, and not just “on the Internet.” Wishnia put it simply: “Nothing creative or independent in our stupid economy is sustainable. I’d like to see arts and comics festivals funded by the government as they are in other countries, so that exhibitors might actually be able to afford to table and make a profit. But like, yeah, right.”

“I think it's sustainable, but I fear it's only sustainable,” says Chapman. “It's hard to see how it will grow to something that reaches outside of its own community. How can the small press be small without being insular?” Chapman notes that Paper Rocket Minicomics, her micropress, is self-sustaining, meaning that her production costs are covered by her sales. “This is not how I make my rent,” she says. “But that's not really a problem for me: my goal is sustainability, not profit. With profit comes compromise.”

Pitzer emphasizes the importance of being a “smart” publisher with a realistic and feasible business plan. “The game seems to change every few months, though”, acknowledges Pitzer. “Just look at Kickstarter, the new direct market. That was a game changer, but who knows what the next one will be? But yeah, if people like myself continue to purchase small-press comics, I think there will always be a interest in them.”

Czapiewski also emphasized the dynamic nature of the industry. “I get the sense that the landscape is the middle of a transition, like our ideas about comics shows are evolving, largely in response to this question of whether or not they can be sustainable. I'm optimistic,” he says. “That said, I have to recognize that even my role models need to supplement their publishing operations with one or more other sources of income. We may not be able to completely sustain ourselves on selling comics, but maybe there are ways to make money from the infrastructure of comics, like printing and distribution (those webcomics guys were trying to make a business as Kickstarter campaign consultants... did that go anywhere?). Also, it may sound counter-intuitive, but I feel like the continuing diversification of the playing field, with more and more different people making and selling comics, is a good thing overall.”

Is the current convention model sustainable, I ask Annie Koyama. "Hopefully," she says, "but it's worrisome that it sometimes feels as if it's the same people buying the books and that we're not reaching a wider audience. Unless more of the smaller publishers can get distribution for their work, I think it's difficult to expand the reach of small press if limited to shows and local comic shops." At this point she sees the benefit of artists and publishers supporting each other through event and promotion partnerships, as well as the utility of having "respected advocates" continue to introduce comics to librarians and schools.

"I don't know. I really don't," says Reynolds in response to my same question about sustainability. "I do think that there might be too much emphasis on shows these days, but I also know that for some small-press creators, the festival circuit is the only way to gain any traction out there in the public eye." I ask him about any potential future roadblocks or strengths he sees as existing in the small-press community, which could affect this sustainability. "The small-press/indie comics economy is a history of roadblocks, real or potential. So sure. It's always a struggle," explains Reynolds. "Strength in numbers can help, and festivals like TCAF and SPX do seem to succeed in their mission of elevating the profile of the art form a bit, through outreach to their communities. But I think it will always be a struggle, because art is a struggle. The late cartoonist Gil Kane once said that 'the good is always in conflict with the better,' and it took me a long time to fully appreciate that, but he was right. Great art will always be threatened by not-great art. Let's face it, the public's appetite for shit is not getting any smaller. That's a huge roadblock, right there."

I detect a bit of cynicism in Reynolds' response and ask him to elaborate about "the public's appetite for shit," as it seems to me this is a time period in which many talented cartoonists are gaining more exposure and respect than they may have in previous eras, and at the same time the 'bar' may be lower for entry into making comics for various reasons (internet/social media, access to production resources, # of shows etc).

Reynolds walks back his "flippant response" and clarifies. "You're absolutely right that on the one hand, we're in this golden age of great comics, and of certain graphic novelists finally getting their due," he says. "But on the other hand, those examples still tend to be the exception to the rule. The bestseller lists are still dominated by middlebrow genre work. Cynical studio tentpole films still top the year-end box office charts. Graphic novels have gained a certain cultural acceptance, but the signal-to-noise ratio hasn't much changed. And it's arguably harder than ever to make a living as a serious cartoonist, even as the art form is flourishing. It was the best of times, it was the worst of times..."

What does Fowler think? Ultimately, he sees the current small press economy as being sustainable. “The magic combination is artists making things they believe are vital contributions to the world, which are also things people want to buy with money," he says. "When you're talking about comics printed on paper, both the artist and the viewer need to feel that the printed paper is the best expression of the content. If you want to make a web comic, make a web comic. But don't expect someone to buy it when you print it out as an afterthought. Print is still the best way to package visual art in a portable, inexpensive format - it just needs to be made purposefully and with intentionality.”

What is clear is that the realities of commerce are inescapable, even for artists who may have intentionally gotten into comics purely for their craft. Terms like "sustainability" are operational on both personal and business levels as well as greater industry ones. Chapman is right: indie comics fall in a peculiar place. In some ways their identity (and their marketability) is defined by their "smallness" and the associated culture's insularity. At the same time, it's the specifics of these realities (coupled with a persistent societal monetary undervaluing of comic art) which may inhibit the small press industry's ability to expand and diversify. Shows like CAB are increasingly vital; not only in bringing together talented creators, publishers, and consumers, but also in creating a dynamic environment in which discussions like these are cultivated.