One could say that Matsumoto Masahiko was the true innovator of gekiga and today’s manga.

Sakurai Shōichi (cartoonist, publisher, brother of Tatsumi Yoshihiro), 1971-72

As an aside, let me point out that, around the time that the term ‘gekiga’ was born, some people used ‘komaga’ instead. In my opinion, it would be more appropriate to call [advanced story manga] ‘komaga.’

Tōge Akane (critic, cartoonist), 1969

Without komaga (literally “panel pictures”), there would have been no gekiga. Moreover, because by the mid 60s gekiga had become lingua franca in comics for adolescent boys and young men, and because without gekiga it is unlikely that the “cinematic” would have become the obsession that it did amongst manga critics and historians, one could also say that without komaga neither manga or its discourse would exist as we know them.

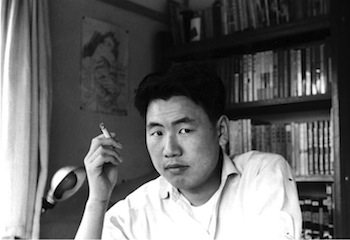

Despite this, komaga’s creator, Matsumoto Masahiko (1934-2005) has only recently been resurrected from the archive. Yet still has his work barely registered within the mainstream of manga scholarship, which remains stubbornly Tezuka-centric in focus.

Most readers of Tatsumi Yoshihiro’s A Drifting Life (1995-2006) will probably remember the importance of Tezuka in the artist’s development. They might also recall the name Ōshiro Noboru, a major figure in children’s comics between the mid 30s and early 50s, who was a key influence on Tatsumi’s cartooning, and through whom Tatsumi succeeded in publishing his first book. But from amongst the cascade of contemporaries that flowed through Tatsumi’s life in the transformative mid 50s, the average reader is not likely to recall Matsumoto Masahiko. He appears in the story as Tatsumi’s slightly senior colleague at the seminal kashihon publisher, Osaka’s Hinomaru Bunko. He appears as Tatsumi’s peer in artistic debates, and as Tatsumi’s rival in creating a new form of comics. But in a way, Tatsumi was (though only a year younger) also Matsumoto’s student. What came to be known as gekiga had many of its own captivating features. Nonetheless, Tatsumi’s much-celebrated manga-that-was-not-manga essentially originated as a form of komaga.

This is not really communicated in A Drifting Life. Without the resurrection of Tatsumi some ten years ago, it is doubtful that anybody other than diehard kashihon collectors and researchers would even know about Matsumoto. But it should also be recognized that Tatsumi, by coining the term gekiga and thus effectively (regardless of his intentions) taking the innovations for his own, did his share in obscuring Matsumoto’s central contributions to the medium. A few years ago I pointed out how Tatsumi was either forgetful or dishonest about his story sources. When it comes to the more important matter of Tatsumi’s visual aesthetic, again I think the autobiographical self-focus of A Drifting Life has skewed art history.

When first introduced in A Drifting Life, around the end of 1954, Matsumoto is simply “a vacant but wholesome-looking man” who had been drawing for Hinomaru since before the publisher was known by that name, and whose books in the judo and humor genres were some of the early kashihon market’s most popular titles. With his longer experience in the kashihon market, Matsumoto advises Tatsumi whom and what to beware of. But it is not until the summer of 1955, with the release of Matsumoto’s deluxe-sized Kaidanji (August 1955), that one gets a glimpse in A Drifting Life of Tatsumi’s jealous admiration of Matsumoto. Judging from Tatsumi’s work from that period, he already had a hungry eye on Matsumoto’s comics style many months before.

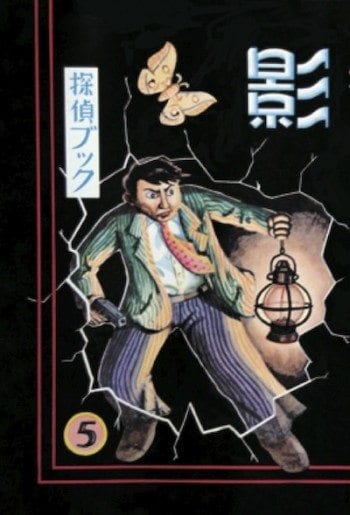

When the idea for a mystery anthology first appears at Hinomaru in early 1956, it is once again the result of Tatsumi’s pursuit of Matsumoto. Desperate to create work in the larger format that Matsumoto had been allowed, but denied the privilege by the publisher, Tatsumi tries to get in through the back door by proposing a two-man collaboration with Matsumoto. Matsumoto agrees to the idea, but once pitched to the publisher it gets appropriated by a jealous elder, Kuroda Masami, Hinomaru’s in-house artist and editorial advisor. The collaboration ends up instead as Shadow, the kashihon market’s first mystery manga periodical and one of the crucibles of the new comics form that would become known first as komaga and then gekiga.

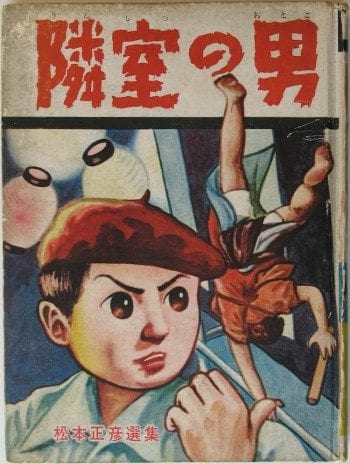

The first issue of Shadow came out in March 1956. The book as a whole is impressive, but what catches Tatsumi’s eye? Matsumoto’s “The Man Next Door” (“Rinshitsu no otoko”), a 30-page story about a cartoonist who imagines a locked room mystery starring his acrimonious neighbors. “As he read the story,” Tatsumi writes about his alter-ego, “he felt as if a blow had been delivered to his head.” Next to a page-wide panel showing Matsumoto’s cartoonist looking out of his window down into the scene of the imagined crime-to-be, Tatsumi continues, “The smooth pacing and big panels that played with perspective were indeed cinematic, but together they created a wholly original atmosphere. Once again, Matsumoto had beaten him to the punch. Hiroshi’s [meaning Tatsumi’s] mind went blank.” Tatsumi is so impressed with “The Man Next Door” that it takes his brother’s intervention to keep him from destroying his already-finished story for the next issue of Shadow.

Matsumoto appears here and there throughout the remainder of A Drifting Life. He, Tatsumi, and Saitō Takao lived together for one month in Osaka during the summer of 1956, an arrangement made by Hinomaru with the hope that the three artists would be more productive away from the distractions of home. Cohabitation had quite the contrary effect, and Matsumoto was the first to decamp, returning to his family in Kobe.

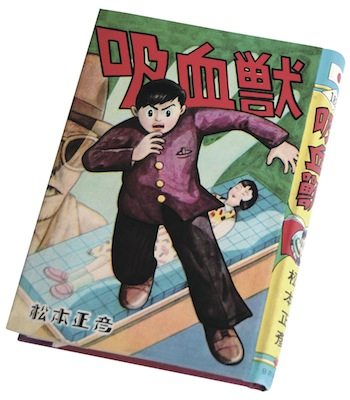

It was immediately after this that Matsumoto began applying to his work the term “komaga” – “panel pictures” – in reference to the “koma”of film frames and in order to emphasize the importance of the panel breakdown in narrative composition in comics. A new name was also a way to differentiate what he was doing from what manga usually connoted: children’s humor comics. “Komaga” first appears on the title pages of his work in September 1956, simultaneously in the book The Bloodsucking Beast (Kyūketsujū) and in “Incident at Shiranui Village” (“Shiranui mura no jiken”), a short story for Shadow. Also appearing for the first time in The Bloodsucking Beast, Matsumoto developed a logo for his manga-that-was-not-manga: a rounded letter M (for Matsumoto) with wings.

In one of the many factual errors in A Drifting Life, Tatsumi dates the first appearance of the word “komaga” much later, to the summer of 1957, putting it closer in time to his own decision to neologize: “gekiga,” or “dramatic pictures,” which was first used for a story published in January 1958. “Komaga sounds like an extension of one-panel and four-panel manga,” complains Tatsumi’s alter-ego. “It sounds a little weak, sort of tame. We’re aiming to create dramatic, epic works. We need a more dramatic name.” Tatsumi too came up with a logo: a rounded G inset with the tag Gekiga Studio. This was over a year after the publication of Black Blizzard (November 1956), the book that Tatsumi has said encapsulated his gekiga aesthetic and that definitively drew a line between what he was doing and Matsumoto’s newly titled “komaga.”

As a character in A Drifting Life, Matsumoto is hardly more than a friendly phantom, in contrast to, say, Saitō Takao, a robust presence endowed with equal parts bluster and talent. From the synopsis above, however, it should be clear how important Matsumoto’s work was to Tatsumi in 1955-56, during which years both artists have said their aesthetics fully gelled. Without Matsumoto’s komaga there would have been no gekiga – a statement with which Tatsumi would agree. But looking at the comics themselves, one could go further and say that the aesthetic Tatsumi pursued in the mid 50s en route to full-blown gekiga was in fact Tatsumi’s version of Matsumoto’s komaga. Tatsumi adopted not only individual techniques from Matsumoto, but also Matsumoto’s overall visual storytelling style. What Tatsumi produced had many of its own innovative features – a combination of komaga paneling with animated cartooning, an emphasis on visual effects, an expressive graphic écriture – and was in many respects much stronger and sharper than what Matsumoto had created. Nonetheless, gekiga’s relationship to komaga was much more filial than the fraternal picture Tatsumi has offered. What his brother, cartoonist and publisher Sakurai Shōichi, wrote in a series on kashihon manga for Garo in the early 70s – “One could say that Matsumoto Masahiko was the true innovator of gekiga and today’s manga” – is much closer to the mark.

What follows is the first in a lengthy two-part introduction to Matsumoto Masahiko and his komaga. It covers the period spanning Matsumoto’s debut in 1953 to early 1956, thus ending before the term “komaga” was coined in the summer of 1956, but dealing with the works in which the core principles of Matsumoto’s distinctive if yet-unnamed aesthetic were most fully operational. Please read this essay as a first draft. I have been meaning to write about Matsumoto for years, but as has been the case with other kashihon artists, my research has been hampered by the fact that early kashihon manga (1953-57) are generally hard to find and expensive to buy. Even the major library collections offering (for-pay) access (the Naiki Library in Tokyo, the Aomushi Shōwa Manga Library in Fukushima) are far from comprehensive. A number of years ago, Matsumoto’s son, Tomohiko, was kind enough to allow me access to his personal collection of his father’s work. Many of the images you see here are photographs taken at his home in Tokyo. Still, even Tomohiko’s collection is incomplete, and so this essay is based on partial research and can only offer provisional hypotheses.

What has finally forced me to take a stab at Matsumoto’s komaga is the publication of The Man Next Door by Breakdown Press. This is a collection of four of Matsumoto’s short stories from 1956, all originally printed in early issues of Shadow, including the eponymous work that floored Tatsumi in A Drifting Life. In some ways, the stories collected therein are not representative of Matsumoto’s komaga, since they are all 35-page-and-under condensations of an aesthetic designed for 100-page-and-over books. Yet according to Tatsumi, in a text accompanying the first-ever compilation of Matsumoto’s kashihon work (2009), this was part of their appeal. “The methods that I thought were only possible in book-length stories were there everywhere in ‘The Man Next Door,’ a work of a mere thirty pages. . . . Today these techniques are commonplace, but ‘The Man Next Door’ had pictorial depth (a sense of perspectival space), a careful calculation of the movement from one panel to the next, and a rapidly changing pictorial composition (cinematic camera work) that shifted the reader’s viewpoint from above to below, also from a diagonal to a bird’s eye view. The members of Shadow were all influenced, in large and small ways, by Matsumoto’s work.” In what follows, I hope to explain what was novel about this komaga style, how it came about art historically, and how exactly it worked.

The release of The Man Next Door marks two events. First, the opening of “Gekiga: Alternative Manga from Japan” at the Cartoon Museum in London, an exhibition spearheaded by Matsumoto Tomohiko in honor of his late father. Second, the beginning of a collaboration between me, Breakdown Press, and the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures to deliver important historical manga in English translation that, because of limited readership and financial viability, would probably not see print without institutional support. If this specific volume has a polemical purpose, it is that of the present essay and its sequel, which is to help round out understanding of postwar manga’s development by challenging the monopoly on gekiga’s inception that Tatsumi functionally claimed for himself in A Drifting Life. Help Breakdown sell this book, and down the road you might see more translations of rare, mid 50s kashihon manga. Black Blizzard and the stories in The Man Next Door are just the tip of the iceberg.

Now, let’s get to know komaga’s originator a bit better, and on his own terms.

(cont'd)