With the publication of the book École de la misère last year, the elusive French-Beninese comics artist Yvan Alagbé returns to expand upon a classic, his 1994 masterwork Les Nègres jaunes. The result, although not without false notes, is an ambitious and moving enrichment of a grand family narrative he has been telling for the past twenty years, and one of the most intricate, challenging, and moving of its kind in comics.

I

Back in the early 1990s, when comics needed a change, the French anthology Le Chéval sans tête ("The Headless Horse") was a glove thrown in the face of habitual thinking. Unabashedly high art in sensibility, it seemed willing to leave behind all the trappings of traditional comics, including those that other innovators on both sides of the Atlantic—from Chris Ware to David B.—were finding such exhilarating new use for at the time.

The anthology was edited and published by two young Parisian artists, Yvan Alagbé and Olivier Marbeouf, under the name Dissidence Art Work. They had previously put out an arts fanzine, L’Oeil carnivore, that informed Chéval, which mixed comics with poetry, photography, and other visual art. The roster of artists they included—people like Andrea Bruno, Martin tom Dieck, Anke Feuchtenberger, Vincent Fortemps, Eric Lambé, Stefano Ricci, Raúl, and Anna Sommer—may not all have become household names since, exactly, but remain significant voices on the edges of the comics medium.

They gradually started producing books too, under the name Amok. Several of these were drawn from material serialized in Chéval, and some of them are overlooked classics: Aristophane Boulon’s Faune (1995), Raúl and Cava’s Fenêtres sur l’Occident (1995), Lorenzo Mattotti’s L’Arbre du penseur (1997, later reissued as Chimera by Coconino/Fantagraphics in their Ignatz series), Muñoz and Sampayo’s Le Poète (1999) and, not least, Alagbé’s own Les Nègres jaunes ("The Yellow Negroes").

It was first published in Chéval in 1994 and then almost entirely redrawn for publication in book form in 1995. In 2012 it was re-released along with a selection of Alagbé’s short stories as Les Nègres jaunes et autres créatures imaginaires ("The Yellow Negroes and other Imaginary Creatures"), preparing the way for École de la misère in 2013.

II

Nègres is one of those works that becomes emblematic not just of its publisher, but of a particular moment in comics. Where the individual parts just click, where every creative decision feels right and supports the author’s intent, while retaining the spark of youthful ambition. Its focus on how issues of race and France’s colonialist legacy shape a set of human relations makes it almost programmatic of Amok’s line of books, much of which strove for a kind of realism engaged in greater sociopolitical context.

It is the story of a young white French woman, Claire, who is in love with a young Beninese man, Alain. An illegal immigrant, he lives with his sister Martine, who makes a living doing housework for well-to-do families, and Sam, a young artist who records key moments of the story in his sketchbook. Sam is a thinly-veiled stand-in for Alagbé himself, adding a dash of mercifully unobtrusive metafiction to the proceedings.

The three of them are hounded by Mario, an Algerian former officer the a paralegal police force tasked with rooting out revolutionary sympathizers in France during Algeria’s bloody war of independence. The reader learns through a third-person narrator, who might just be Mario talking to himself, that he was among those responsible for the notorious massacre of around 200 pro-Algerian demonstrators in Paris on October 17 and 18, 1961.

As a harki, i.e. Algerian loyalist, he is persona non grata in his homeland where sympathizers of the former government were rounded up and killed en masse following the war of independence. But he is also a political outcast in France, where the authorities he served did their best to wash their hands of their former allies, offering them no help as the new, independent Algerian government exerted their gruesome revenge. Many of those who remained in France were imprisoned in camps as illegal immigrants and only slowly accorded basic rights.

Although Mario was clearly too well-connected to have suffered this fate, he is cast as a pariah, his loss of national identity directly reflected in his state of profound loneliness. His successful doctor daughter avoids him, and he seeks human closeness among people in positions of weakness, like the Beninese siblings. As sans-papiers, they are receptive to his offers of help, offers that draw upon his past as a police officer. Given his state of disgrace, these are entirely illusory, but there is also some self-delusion mixed in with his dishonesty. He so strongly identifies with his former job that part of him believes his own deception, giving him purpose.

That Mario is Alagbé’s most fascinating character is telling, in that he personifies more strongly than any of the others the wages of colonial sin that the author is examining and criticizing in this book. Unacknowledged sexual anxiety feeds Mario’s effusive but blinkered approach to the objects of his attention, leaving him to reproduce the repressive, exploitative behavior he internalized on the job. He is an emasculated, lost agent of a history that is still very much alive.

Initially more of a blank slate, Claire would appear to be his opposite number. Her name itself indicates her seemingly unfiltered approach to the social context entangling the people around her. She is the least prejudiced character in the book, in love with Alain. It is clear, however, that this attitude has come at a cost. She is alienated from her divorced father, who strongly disapproves of her choice, and we sense a troubled family background.

As for Alain and Martine, they are the most obviously vulnerable in this system of mutual oppression, and indeed suffer for it. To Alagbé’s credit, they are not uniquely described as victims—Alain, especially, has an exploitative side to his personality, which clashes with his vanity and his pride. He takes advantage of Mario, but resents his increasing dependence on his money and promises, and it becomes his undoing.

It’s a tragic tale. In part it is an impassioned indictment of French institutional racism and an inhumane immigration system, but more profoundly it is an analysis of an oppressive social world determined by colonial history—to be combated, sure, but primarily to be reckoned with.

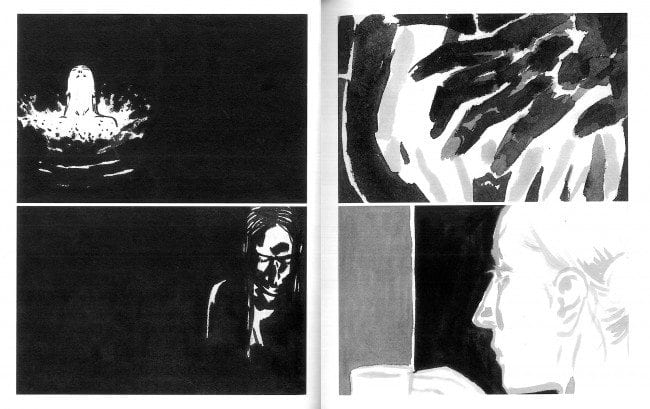

Alagbé’s brush-and-ink cartooning is alternately lush and sparse, scruffy and exacting, black and white, with echoes of Muñoz and Aristophane Boulon. He selectively lends texture to areas of focus, while leaving others defined only by contour. Although he makes selective use of symbolic passages, he is a realist at heart, attentive to facial and bodily expression. At times he errs on the side of the obvious, but he also occasionally catches real moments of ambiguity as well as emotional clarity—the combination of apprehension, skepticism, boredom, and impotence drawn on the faces of the siblings listening to Mario’s tales of African adventure; the genuine expression of affection shown by Mario as he speaks to his daughter on the phone; and so on, moment after moment.

Alagbé modulates his rendering skillfully. Everybody, whatever the color of their skin, alternately appears lighter or darker, and specific physiognomic traits, particularly those of the black Africans, are occasionally emphasized to contrast strongly with their white surroundings, reflecting the social context. The point, however, seems to be that in a graphic world consisting uniquely of black marks on white paper, everybody is black.

III

Alagbé’s comics production has been modest. He has been involved in various collective projects of politicized autobiography, including a couple with his sister Hélène, which are not strictly comics. In 2001, Marboeuf had left Amok to pursue a career in other media, while Alagbé joined forces with the Belgian avant-garde publishing house Fréon to form Frémok, or FRMK.

Until recently, his most substantial publication at this structure was the book Qui a connu le feu (Who has known fire, 2004), written in collaboration with artist Olivier Bramanti (read my 2004 review here). It stages a hypothetical conversation between a colonialist and an anti-colonialist: the sixteenth-century king of Portugal, Sebastian I, and Béhanzin, the late nineteenth-century King of Dahomey—the land that was to become Benin. It mixes the political speeches of the latter with excerpts from the poetry of Luis vaz de Camoes and Fernando Pessoa, as well as other texts, to form a symbolic mediation on colonialism and its legacy visualized as a portentous suite of black faces and bodies interspersed with symbols of imperialism. An ambitious, intense, and thoughtful, but also somewhat haughty work.

Over the years, however, Les Nègres jaunes has remained the touchstone of Alagbé’s career as a comics artist. A breakthrough so authoritative that it has continued to reverberate in his work over the years, it is his Maus, so to speak. In 1997, he returned to the cast of Nègres with two short stories. One, Dyaa, was released as a stand-alone book (and is included in Les Nègres jaunes et autres créatures imaginaires). It explores Martine’s past, her arrival in France and her tragic romantic involvement with another immigrant.

The other, written in collaboration with Éleonore Stein, is called “Le Deuil” (‘Mourning’) and was published in Chéval no. 4. It fleshes out the story of Claire. At the sudden death—by suicide, we understand—of her paternal grandparents, she returns to the family’s countryside house to be reunited with her brother, uncle, and estranged father. Her relations with all of them are explored, and we understand that she spent part of her childhood in her grandparents’ city residence, part of which they ran as a whorehouse serving a diverse immigrant community. Another revelation is an album of photographs taken by her grandfather in Cameroon in his youth, some of them sexually suggestive pictures of young girls. An extended, but inconclusive reckoning between Claire and her father also occurs.

IV

It is this rather unresolved story that Alagbé now has picked up and developed further in École de la misère ("School of Misery"), a book on which he has been working since the publication of “Le Deuil". It greatly expands upon the original, adding layers both to it and to Nègres, though it has to be said that Alagbé is at his most suggestive here. So much remains unsaid that even for those familiar with the preceding stories, many of the particulars of the present narrative remain ambiguous, not to say nebulous. Without knowledge of the earlier material, the reader may feel lost.

So the price of admission is high, but the book nevertheless deserves attention. It is a bold and nakedly intense effort to represent the way bereavement may trigger memories, dreams, and rationalization, as well as to describe how, like it or not, family dictates our lives.

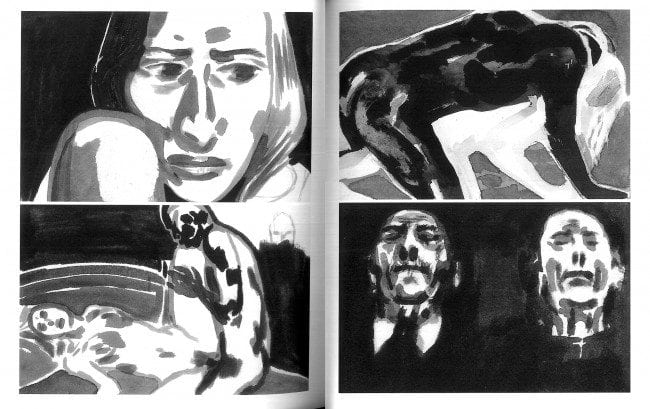

Where the previous stories were rendered in starkly brushed black and white, École is painted in lush, dark ink wash, offering many shades of grey. The printing by photogravure—always done so beautifully by FRMK—and heavy paper stock add meaningfully to the sense that this is a precious object, perhaps (appropriately) like a family heirloom.

The storytelling is decompressed, as they used to say in American mainstream comics a decade or so ago, with two large rectangular panels per page. Alagbé weaves together rather punctiliously various strands of his narrative to suggest, in a kind of mosaic, Claire’s flow of consciousness—a family album of the mind. One strand is the expanded version of “Le Deuil”, which prompts a range of flashbacks—we learn that Claire spent part of her childhood at her grandparents’ city home/bordello, and that her grandfather strongly disapproved of her naively stated desire as a tween to marry a black man. Connections are made to his youth in Cameroon, where we understand that he worked as part of the colonialist apparatus, and to his own repressed desire for black women revealed by the photos taken there that Claire and her family discover.

This complicates Claire’s character, suggesting that she is reproducing prejudices and desires that run in her family and implicating her emotional reactions in a wider social context haunted by the specter of colonialism and racism. Suddenly, we realize that she and Mario, the apparent polar opposites of Nègres, are united at a profound level. While clearly genuine, her love for Alain—whom she lost at the end of Nègres—is tainted by factors utterly beyond her control.

Alagbé further compounds this by interweaving his narrative with an extended scene of passionate, graphic sex between Claire and Alain—a memory that clearly haunts her and defines her feeling of emptiness. Again, there is no reason to doubt that her love for Alain was genuine, nor that their physical connection was real, but by thus emphasizing the latter, Alagbé suggests that there is a fetishistic side to her desire—as indeed there may have been to his—inextricably tied to inherited racial prejudice.

Other important tesserae in Alagbé’s mosaic include an extended and, we sense, recurring daydream about what might have happened between Claire and Alain, had what actually occurred not taken place. This is juxtaposed by an extended replay of the tragic ending of Nègres. The reasons for the confrontation between Alain and Martine, which precipitated that particular chain of events, are also expanded upon and a repressed history of abuse is implied, with connections also being drawn to the events previously sketched out in Dyaa.

This unites Martine and Claire, whom we come to understand was also the victim of abuse at the hands of her father. This is the least satisfying part of the book, in that it feels slightly too predictable—like Alagbé overplaying his otherwise strong hand. His attempts to also tell the sad story of the father’s later life consequently fall a little flat.

In the end, the macro-story Alagbé has been telling over the past twenty years is about the cages we inhabit as social beings in a determined historical flux, cages that are doomed to ever to reproduce themselves. The pessimism is palpable, but where Nègres and its follow-ups in the nineties withheld any promise of redemption, École—colored by the ambiguities of age—offers it in the very quintessence of reproduction, ending as it does with an innocent smile.