Comics Unmasked is Britain's largest-ever show about UK comics. It also offers the first public peek at the British Library's enormous comics collection. However there's more to see than just a Rolodex of auteurs or a trip down memory lane. The exhibition's "unmasking" delivers what its subtitle promises – examples of how, from their very start, British comics have revelled in both and art and anarchy.

On display are over two hundred original scripts and sketches, artefacts and rarities, with a large number of loans from artists and collectors. Fans will find absorbing work from all the big British names – Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, Eddie Campbell, Steve Bell, Posy Simmonds, Grant Morrison and more. The expo also features an ingenious mise-en-scène (specially commissioned from Dave McKean) as well as its own signature graphic heroine. Created by Jamie Hewlett and nicknamed 'Lawless' by Library staffers, she is a sulky crime-fighter slouched in an alley.

Lawless is the perfect symbol for this show about graphic dissent, executed with great verve by co-curators Paul Gravett and John Harris Dunning. Partly thanks to its series of associated events (author appearances, conversations, workshops, signings, curators' tours and day-long conferences), it has broken attendance records at the Library. "The whole thing," says Gravett, "is a really unique experience. Especially since, at this venue, the term 'modern' means 'after 1500'."

The show does feature some artefacts of astonishing age: pages from a 15th century Biblia pauperum (a block-book Bible whose sequential style has startled viewers) or a detailed 17th century book of magician's spells. Yet, ever since they could, British people have loved to read. What this show highlights is their enduring obsession with visualised narratives – here displayed in broadsides and chapbooks, pamphlets and periodicals, newspapers, journals and illustrated gazettes.

Britain was the home not only of Hogarth and Gillray, but also Punch and Judy, Charles Dickens and Cruikshank. In terms of narrative satire and storytelling, work by figures like these has profoundly shaped British perceptions. Maybe critic Thierry Smolderen is right that comics are all anarchic. But Comics Unmasked confirms that the British comics tradition, at least, has structural roots in rebellion.

From mischief-making in kiddie strips to chronic debunking of order and class; from satire about the opposite sex to mockeries of manners and style, the British definition of "anarchy" asks that its viewer question everything. This is illustrated over and over throughout the show – from The Magic Beano Book's Snitch and Snatch in '49 to Tank Girl in the '90s or 2010's Kick-Ass. But nowhere is it more intriguing than in the forgotten characters Gravett and Dunning have brought out of the UK's past.

One such example is the 19th century's Ally Sloper. Sloper was the image of a lazy, tippling British worker recognised by Victorians as widely as the Simpsons are now. He was created by the novelist Charles Henry Ross. However, this British stereotype was mostly drawn by Mrs. Ross – who happened to be a Frenchwoman called Isabelle Émilie de Tessier. The show features some stunning examples of Sloper merchandise, including a ventriloquist's puppet used in the 1890's.

The exposition has six sections, each with a different theme. These divisions let it counterpoint the old and new; they also help viewers grasp how characters and concerns have endured with passing times. The first three sections (Mischief & Mayhem; To See Ourselves; Politics, Power & the People) also break down British comics' history of scepticism. Many of the artefacts found here are fascinating. An 1888 Illustrated Police Gazette, for instance, has an all-pictorial, as-it-happened front about Jack the Ripper. Right next door, you can study From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell.

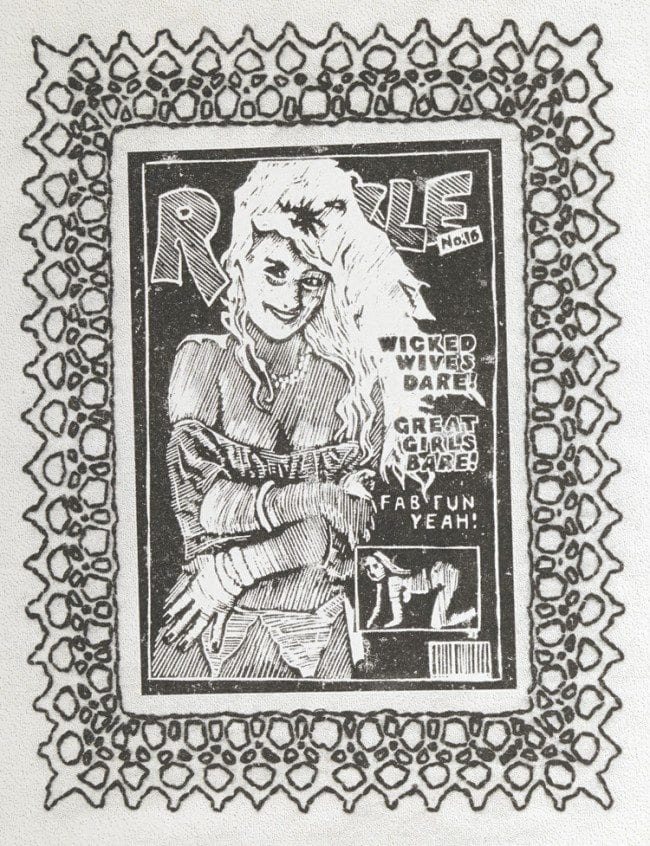

These sections are succeeded by Let's Talk About Sex and Hero With A Thousand Faces. The first is an in-depth look at UK "underground" comics which includes the 1971 Oz obscenity trial. (Erotica, gay issues and various sexual narratives are presented in their own protected, signposted space). The section on Heroes, critically, handles the US comics invasion. Here, Gravett and Dunning point out how the horror, crime and superhero sagas burst upon a nation still traumatised after the War. That Britain remained a nation subject to deprivation and rationing. It had also yet to emerge from an era when "moral unities" had been a matter of psychic survival.

This context helps explain the '50s indignation of parents, groups and authorities in the face of Black Magic, Tales From the Crypt, Crime Suspense Stories, etc. (It's frank, too, about how anti-Americanism alternated with the lure of profits to be made from these very genres.) The response of British creators to such American imports – especially in the reinterpretations they later offered – helps illuminate Anglophone comic culture today.

The exhibition's scheme functions less well in its final section, which is called Breakdown: The Outer Limits of Comics. Dedicated to disobedience as defined through "magic" and drugs, its historic input (like the Victorian era's use of laudanum) gets too muddled up with post-'60s psychotropics. Yet the show as a whole provides genuine, landmark insights.

UK comics are frequently linked to 18th century satire, Victorian caricature and so forth. But here, via pieces that are both rare and original, visitors see the depth of that continuum between Britain's real radical past and rebellion in her comics. Thus Comics Unmasked clarifies more than random characters and allusions. It helps us understand what gives UK comics their "Britishness".

• Comics Unmasked continues at London's British Library through 19 August 2014 (a parent or carer must accompany visitors under 16).