A Mad Look at Toes by Craig Fischer

I’m bugged by much of the mainstream media attention given to Al Feldstein’s passing, because it feels less about the editor himself than about websites providing Boomers with yet another opportunity to wax nostalgic: “Mad’s editor died? Too bad. Hey, do you remember ‘2001: A Space Idiocy’?” For me, Feldstein’s 28-year editorial run shouldn’t be simplified to clichés about Mad’s irreverence. Feldstein’ achievement is more ambivalent than that, as much about Fordist efficiency and lost opportunities as about the supposed cultural subversions of the “usual gang of idiots.”

This ambivalence creeps into the interviews Feldstein gave to the Comics Journal. In the interview with Gary Groth posted on TCJ.com last week, Feldstein talks lovingly of the friendship he and Bill Gaines developed as they worked together on the E.C. Comics, after Gaines had been through a painful divorce and while Feldstein’s own first marriage was failing. Feldstein has harsh words, though, for E.C. business manager (from 1952-54), First Amendment advocate, and publisher Lyle Stuart, who encouraged Gaines to speak at the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency (“definitely not a good idea,” says Gary Groth, understatedly) and also probably broke apart Feldstein and Gaines’s collaboration. As Feldstein says in last week’s interview:

I don’t know how it happened, when he [Gaines] made this decision that he no longer wanted to spend nights reading and to bring in springboards, and that I should work with other writers and give up that particular pattern of creativity that we had worked on for so long. He then announced to me that he was going to give me my own office, one story up, for me to entertain writers and to do my work--and actually the intention, I assume, was to get me out of the office, so I wouldn’t know what’s going on as far as Lyle’s advice to him was concerned.

Stuart wasn’t too fond of Feldstein either. In Squa Tront 12 (2007), Stuart described Feldstein as “an inadequate personality. His values seemed superficial and he seemed to be a plastic man” (53). Whatever the reason--Stuart’s interference or other factors--the relationship between Gaines and Feldstein had become strained; the gleeful co-conspirators of the early E.C. days had become publisher and editor, employer and employee. Then, after Feldstein took over as Mad’s second editor, Gaines increasingly divorced himself from day-to-day operations, sometimes only looking at an issue immediately before it went to press, while Feldstein turned the magazine into a post-war publishing sensation.

Did Feldstein enjoy his career as Mad editor and employee? In his interview in The Comics Journal #225 (July 2000), Feldstein tells stories about the good times--posing for satirical ads (several of which can be found here), going on the legendary staff trips--but includes some serious grievances about the way he was treated at Mad too. He argued with Gaines for a “piece of the magazine” (a percentage of gross profits) after Gaines sold Mad for tax reasons in the late 1950s (p. 68), and he complained about being “written out of Mad’s history” after a 60 Minutes piece focused exclusively on the current “gang of idiots” (p. 68). More trenchantly, Feldstein believed that Gaines’ model of running Mad refused to evolve with the times:

That was part of the problem I saw when I decided to retire in ‘81. We weren’t going anywhere. I wanted to bring the magazine into the ‘80s, the ‘90s, and Bill didn’t want to have any part of it. We had a lot of...discussions [laughs] about the future. I felt the future was bleak. (p. 79)

So Feldstein served out his last contract with Gaines (from 1981-84) and then left the magazine. It’s odd that he resented Gaines’ unwillingness to update Mad, since I’ve always believed that Feldstein’s own editorial policy was based on stasis as well. He was undoubtedly superb at recognizing talent when he saw it: he and Gaines recruited Aragonés, Berg, Drucker, Martin and Prohías, among others, to Mad. Once these stellar talents were working regularly for the magazine, however, Feldstein appears to have encouraged (or at least allowed) them to do the same material from year to year: The Lighter Side of Spy vs. Spy Movie Parodies. Consequently, Mad became a fad that the kids in my neighborhood outgrew--when we were 11 years old, we were thrilled by its irreverence, but we stopped reading it at age 13 because we were tired of its formulas.

One of my favorite comic books of recent years is Bongo’s Sergio Aragonés Funnies, because it’s a venue where Sergio was free to draw folk tales, puzzles, and autobiographical stories (some of which chronicle his career at Mad). In Funnies #12, the most recent and (for now) final issue, Aragonés recalls his encounters with Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune: meeting him on the Mexican set of the film Ánimas Trujano in 1961, having him over for dinner at his family’s home, catching up with him two decades at an L.A. parade. The second-to-last panel of the story features Sergio summing up his impressions of Mifune and his talents:

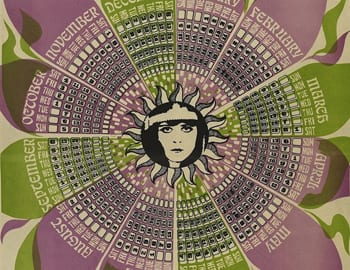

Sergio watches Mifune’s magisterial turn in Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), but note that the title of the strip on his drawing table is “A MAD Look at Toes.” Is Aragonés bored with Mad’s shticks too? What kind of magazine would Mad have been if Sergio’s personal stories had been published there? Or if Gaines and Feldstein, both fully committed to collaboration, had brought some of the energy and transgression to Mad that they’d devoted to the early E.C.s?

When I met Feldstein in 2008, I found him a gracious and generous man--generous enough to allow me (and Ben Towle, Roger Langridge and Richard Thompson) to interview him for a Heroes Con panel. He made a lot of money with his “piece of the magazine,” he was universally adored by adolescent smartasses everywhere, and he had three decades of an artistically fulfilling third act as a painter after leaving Mad. He deserved his success. He won. Yet Feldstein’s 28-year run as Mad editor is perpetually eclipsed by the 23 comic-book issues Harvey Kurtzman wrote and edited, and when I try to read issues of the Feldstein-edited Mad today, my attention slides off them like they’re frictionless. I wish this good man had left a more vibrant legacy.

The Power of Albert B. Feldstein, the editor of Mad by Mark Newgarden

Part 1.

“My name is Albert B. Feldstein and I am the editor of Mad.”

“My name is Albert B. Feldstein and I am the editor of Mad.”

“My name is Albert B. Feldstein and I am the editor of Mad.”

My copy of the little square cardboard Meet The Staff Of Mad flexidisc skipped here and it never, ever occurred to nudge that needle forward. It only got funnier. One rainy night I let it play for a good 45 minutes until my little brother began to cry.

Part 2.

Towards the end of fifth grade I apparently considered Albert B. Feldstein my favorite author and registered this information for posterity on the appropriate blank line in my groovy purple PS 45 graduation autograph book. I subsequently felt a tinge of guilt since I knew this wasn’t the sort of literary figure that the autograph book manufacturer had in mind for me and amended it with a qualifying “(EDITOR.)”

Part 3.

I later learned that the Mad paperback reprints that I loved above all were the work of Harvey Kurtzman, the editor of Mad, not Albert B. Feldstein, the editor of Mad. And today I learned that Albert B. Feldstein was dead at 88 and had taken to painting wild west scenes in his golden years. The New York Times covered the story with this headline: “Al Goldstein, the Soul of Mad Magazine Dies at 88.” I was also informed by Drew Friedman that the recorded voice on that flexidisc was in fact associate editor Jerry De Fuccio impersonating his boss, whose speaking voice was deemed “too Jewish.”

So now I’m at a complete loss.

(But God bless Albert B. Feldstein, the editor of Mad, anyway.)