In many ways, 1939 and 1940 were pivotal years in Jack Cole's life and work. These are the years he stretched from humorous short subjects to longer, more serious crime and superhero stories.

Cole's growth reflects the rapid growth of the American comic book industry, which was mainly propelled by the superhero boom in these years. Cole's output climbed from about 50 comic book pages in 1938 and 66 pages in 1939 to around 200 pages in 1940.

These, then, are the formative years when Jack Cole developed from a struggling gag cartoonist into a professional visual storyteller destined to become a master of the form.

As Cole stepped up his game, probably for economic reasons as much as artistic, his stories became increasingly weird (and therefore, entertaining) expressions of a singular world view – one that had both genuine mirth and lengthening shadows that hinted at a dark side to the prankster inventor.

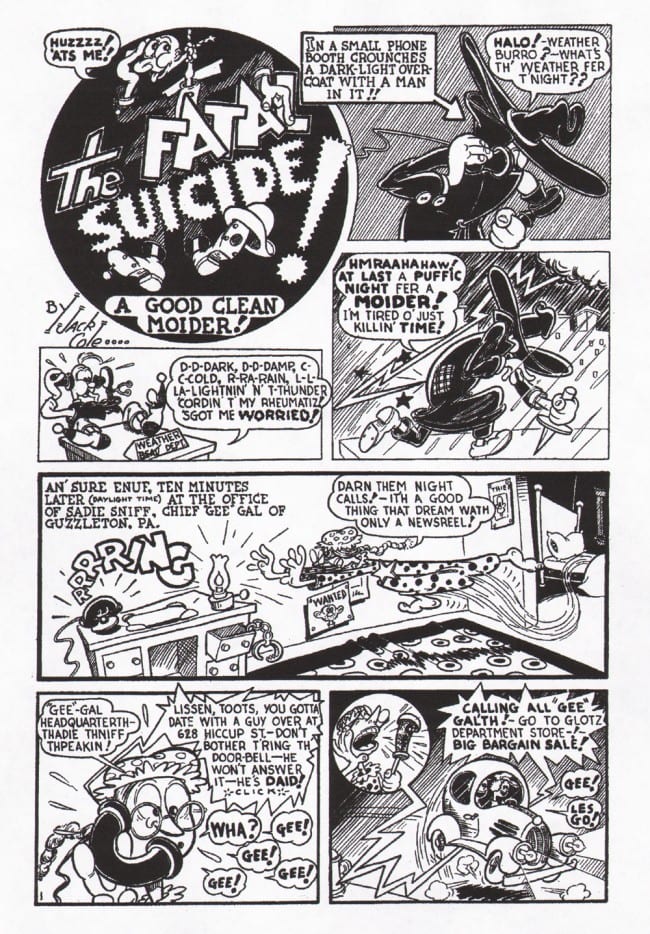

Consider his manic four-page screwball farce published in the March 1939 issue of Funny Pages (Volume 3, #2) entitled “The Fatal Suicide." This story appears to be the first of perhaps dozens of instances in which suicide appears in his work. When one knows that Jack Cole took his own life in 1958, it's impossible to escape the ominous foreshadowing presented by the shrill suicide gags in this story. "I'm tired o' just killin' time," the seemingly murderous villain cackles on page one, amid nighttime rain, lightning, and thunder.

After four head-spinning pages of high octane visual-verbal gags, it turns out the murderer's victim is himself -- a man named Rigor Mortis who appears to be very much alive, despite the dagger in his heart -- but insists he is "DEAD!"

One must be careful not to read too much into such things, but a smiling, suicidal man with a a dagger in his heart and a comic book in his hands undeniably resonates with what we know of the man who created this story. A black and white complete version of "The Fatal Suicide" can be found in The Best of Jack Cole, edited by Greg Theakston (Pure Imagination Publishing, 2006).

"The Fatal Suicide" stars one of Cole's short-lived characters, a decidedly un-sexy, gawky, quasi-policewoman named Sadie Smith. The character only appeared in one other story, which came out the month before "The Fatal Suicide." The story was set in the fictional town of Guzzleton, Pennsylvania -- a nod to Cole's hometown of New Castle, Pennsylvania (about a year later, he would set his Dickie Dean stories in New Castle).

The splash page of of the first Sadie Smith story is notable for the streamlined, diagrammatic cartooning and ever-present narrator story structure that Cole briefly played with -- an approach that vanished for almost 20 years until 1958, when it resurfaced with great refinement in his syndicated comic strip, Betsy and Me.

Up to about 1939, Cole's work had been pure expressions of the sort of screwball comic that peaked in American newspapers during Cole's boyhood. Artists like Rube Goldberg, Milt Gross, Gene Ahern (The Squirrel Cage, The Nut Brothers), and Bill Holman (Smokey Stover) had shaped, forged, and polished the screwball comic template for at least two generations before Jack Cole came of age.

The work Cole created from 1936 through 1938 at the Chesler shop was only a shade different from the humor comics of a half dozen other artists in the same room; a little quirkier, a little more clever. In 1939, with stories like "The Fatal Suicide," Cole's version of the gleaming, buffed screwball comics template developed hairline fractures, and his comics thereafter offered a mix of comedy and despair so singular and personal that no other creator has been able to work with his popular Plastic Man character in a way that comes close to Cole's version. It's these cracks, through which a sense of the darker realities of human experience seep, that makes Cole an interesting artist.

Pitooie! Jack Cole's Magazine Gag Cartoons of 1939 and 1940

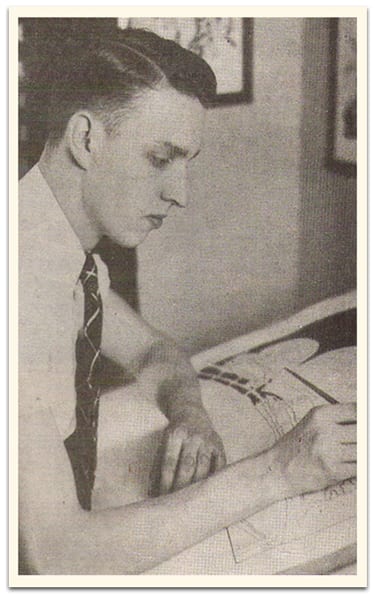

Among the lost gems of Cole's work are his published magazine cartoons. While he toiled days in the Chesler comic book sweat shop, Cole also ambitiously worked on his fledgling career as a magazine gag panel cartoonist, probably at nights on the kitchen table in his Greenwich Village apartment. This was, after all, the reason he had moved to New York: to make it as a magazine gag cartoonist and perhaps someday have a syndicated comic strip. He even managed to sell several cartoons to leading magazines -- most of which have not seen the light of day since their original appearances in the back pages of weekly and monthly magazines.

None of the books published on Cole thus far reprint these cartoons, or offer much more than a sentence or two about them. Ron Goulart's excellent essay, "Jack Cole, Gag Cartoonist," (Comic Art #2, Winter 2003) understandably focuses on Cole's astonishing non-Playboy sex cartoons of the 1950s. As more and more of these early lost Jack Cole cartoons are found, it becomes clear that they represent an important part of his output in his formative years. One might almost think of Cole as pursuing two careers at the same time - one (magazine and comic strip cartoonist) with great intention, and the other (comic book artist) a sort of accidental occupation.

It's tantalizing to consider that these early published cartoons may be merely the tip of the iceberg, and that dozens of unseen Jack Cole cartoons were roughed out and finished in 1939-1940 and later lost to posterity, either destroyed in the flood of his home a decade later, or discarded by his widow, who refused to have anything to do with Jack's work after his death.

From 1936 to 1938, Jack Cole sold 16 cartoons to Boy's Life. As he became more and more entrenched in the new, anything goes art form that was rapidly developing in comic books, Cole sold fewer and fewer gag cartoons to magazines. In 1939, he placed six cartoons in Boy's Life, and the following year, just three, and none in the magazine after October, 1940.

Jack Cole's 1939/1940 cartoons for Boy's Life displayed impressive advances in technique and confidence, foreshadowing the superhuman leaps he would later make when he returned to the form in earnest during the mid-1950s.

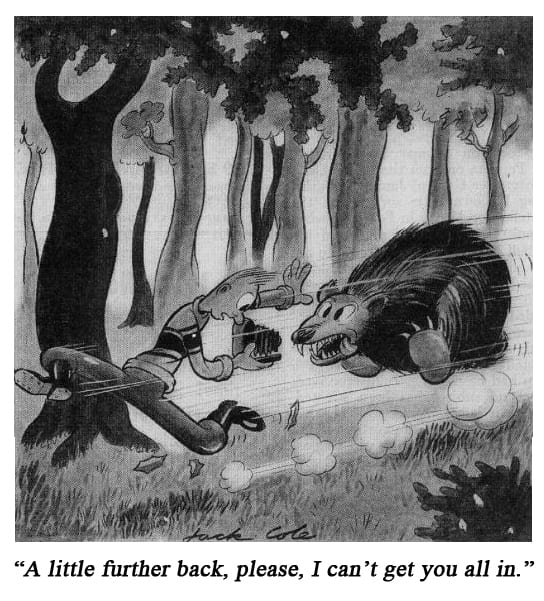

Jack Cole's last cartoons for BOY'S LIFE show the same comically furious energy that later manifested in his comic book stories. His cartoons evolved from tentative, static poses into bold split-second snapshots of forms in motion; they could have been frames taken from the crazed action sequences in Tex Avery cartoons. His lines were bold, curved, and sweeping. Cole laid in larger areas of blacks and grey washes, causing the "pure" whites to seemingly leap off the page. His compositions masterfully organized spatial vectors so that he precisely controlled the movement of the reader's eye across the drawing.

His gags, mostly corny and forced, took a secondary role to his increasing vital visuals. He drew a pole vaulter in mid-vault, a thrown bronco rider flipping and falling, and an airplane not just descending, but sucked down out of the sky. Even his bold rendering of a blown tuba had a disarming energy to it as if a secret message were encoded into the caption-less sight gag.

Cole's bold depictions of humorously quick and soaring movements anticipate the manic energy of his later comic book stories, where at times he seemed obsessed with the idea of capturing speed on paper. It is in the comically furious energy of Jack Cole's 1939 and 1940 Boy's Life cartoons that one can first see the mind that would later draw Plastic Man in a single panel stretching from a city sidewalk, through an open third-floor window, into a glass of liquid and up the straw to confront a crook that is so started he is jumping out of his clothes while dropping the glass.

Cole also continued to place cartoons in Collier's, a weekly magazine read by millions. As with his work in Boy's Life, his Collier's cartoons evolved in style and confidence -- but in an altogether different direction. In the cartoon published in the May 20 issue of Collier's, Cole uses a jumpy, impressionistic line -- his first steps towards the acclaimed painterly Playboy cartoon style he mastered in the mid-1950s.

Jack Cole made only two more sales (currently known) to Collier's in this period, and both appeared in the September 2, 1939 issue. One was a decent gag about Joe Dimaggio in which Cole cleverly avoided the pitfalls of an attempted recognizable caricature of the baseball star. The cartoon is done in the same wash style employed in Cole's later Boy's Life cartoons.

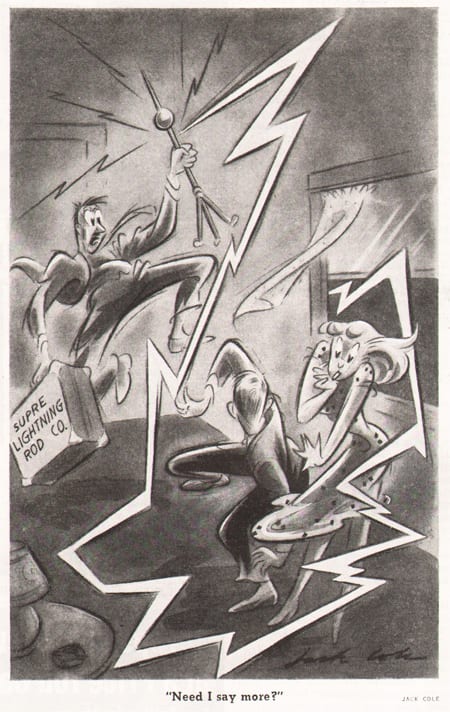

Cole's second cartoon is one of his best, and another in the wild, freeze-frame approach he developed around mid-1939. In this bold cartoon, Cole captures a lightning bolt, and -- one might say -- lightning in a bottle.

The eye-candy aspect of a zig-zag bolt of lightning, as well as its symbolic verve was not lost on Jack Cole, who included numerous jagged flashes in his comics of this period. Cole's lightning bolts are just one of several such visual tropes he consciously developed to make his art more exciting and appealing. Other examples of Cole's visual tropes include the black and white prison stripes in his Death Patrol stories, ejaculating volcanoes, and zooming automobiles that moved so fast their wheels rarely touched the ground.

Early Crime Stories

In 1939 and 1940, Jack Cole created some of the first of the "true crime" comics, a genre that would become a massive hit in comic books in the 1940s. Though he created only thirteen “true” crime stories in his entire sixteen-year career, Jack Cole’s two Tommy gun bursts of crime storytelling, in 1939-1940, and 1947-1948, grazed the genre and left an indelible mark.

Spurred on the various magazine and book writings of the notorious child psychologist Frederick Wertham, various early 1950s governmental commissions singled out-- among dozens of other examples -- some of Cole’s 1947-1948 crime stories (as well as his Plastic Man stories) as prime examples of publications that fostered juvenile delinquency. The anti-comics controversy contributed to the near death and desperate metamorphosis of the industry in the early 1950s, prompting Jack Cole and many other comic book pros to leave comic books for good. Cole’s involvement in the whole fracas began in 1939, when he first turned his attention to crime comics, producing six stories during 1939 and 1940. The stories,not reprinted in nearly 75 years or widely known, are:

- 02/39: “Little Dynamite (Keen Detective Funnies V2#2, Centaur)

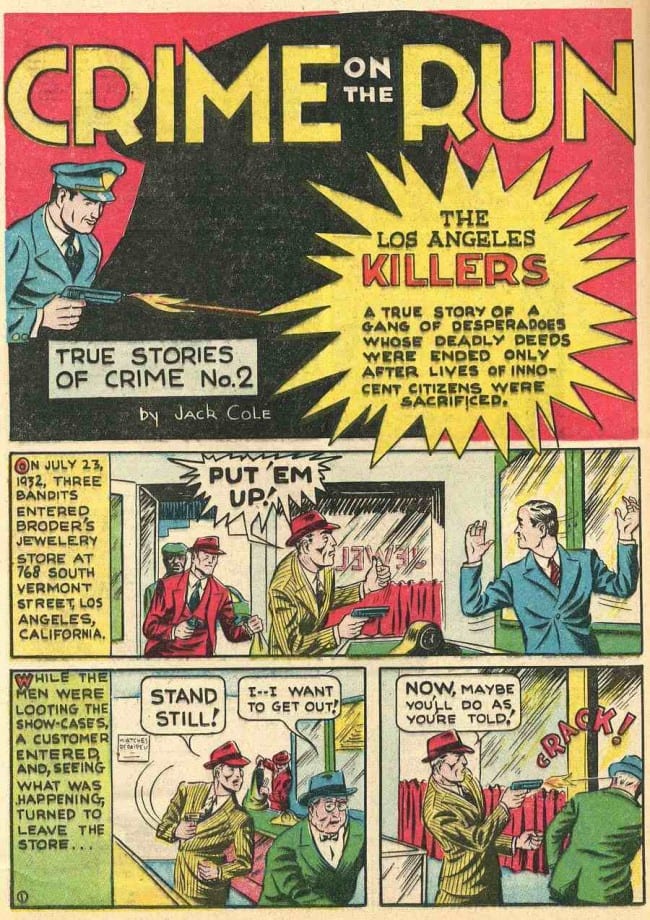

- 11/39: Crime On The Run (Blue Ribbon Comics #1, MLJ/Archie)

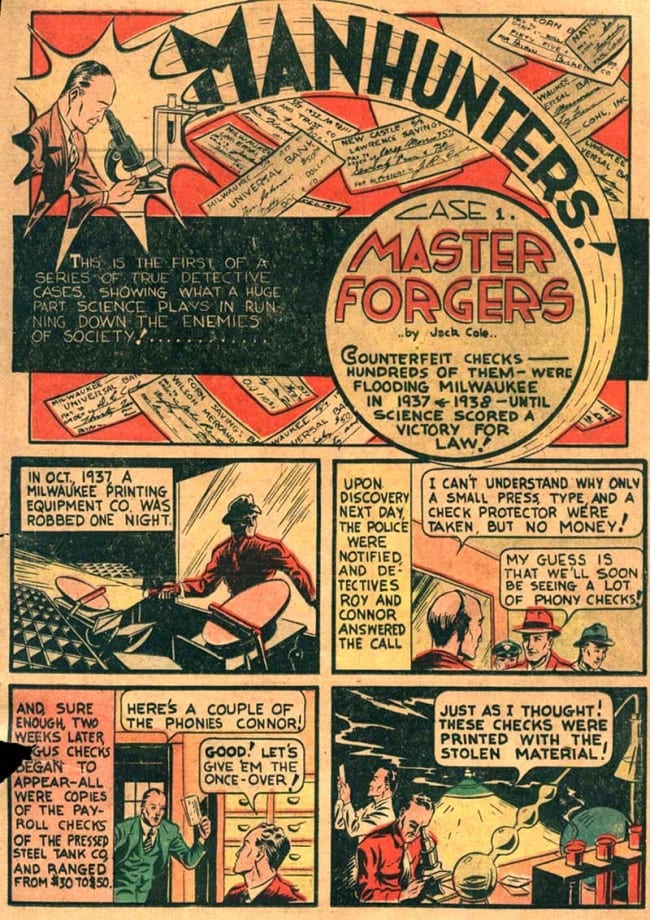

- 12/39: Manhunters (Top Notch Comics #1, MLJ/Archie)

- 01/40: Crime On The Run (Blue Ribbon Comics #3, MLJ/Archie)

- 01/40: Manhunters (Top Notch Comics #2, MLJ/Archie)

- 02/40: Manhunters (Top Notch Comics #3, MLJ/Archie)

“Little Dynamite,” Jack Cole’s first crime story, appeared in the February, 1939 issue of the Centaur published Keen Detective Funnies (you can read the entire story in The Lost Comics of Jack Cole, Part 2).

The six-page saga was drawn in a heavy, dark style that was unlike anything Cole had done up to that point, and dissimilar from any work that came afterward. In much the same way that the playful visual style of Cole’s Plastic Man stories is perfectly suited for telling stories about a man who can stretch and mold his body into almost any shape, the determined, awkward quality of Cole’s art in “Little Dynamite” resonates with the content, which centers on a grimly resolute policeman who happens to be a little person.

For the rest of his crime story spree, Cole ambitiously created two new, short-lived series: "Crime On The Run," and "Manhunters." This was material that he created at the Harry "A" Chesler shop, which supplied original comic book content to various packagers and publishers. As comic books became a newsstand sensation, new publishers sprang up overnight, and most faded away just as quickly. One publisher that did not fade away, and which is still in existence today, was MLJ, which later became Archie comics. Through the Chesler shop, Cole supplied solid content -- both humorous and crime-oriented for two of their new titles, Blue Ribbon and Top-Notch.

Of Cole's humorous content that appeared in the MLJ/Archie books, "Knight Off," a manic one-pager was notable for the interesting, organic panel shapes that Cole employed to add to the visual dynamics of an otherwise unremarkable gag.

"Crime On The Run," Jack Cole's two-issue crime series that ran in Blue Ribbon Comics focused more on the criminal experience from the bad guy's side. The series tries to be slightly more lurid and sensational than "Manhunters,", even though Cole's art doesn't quite live up to the task.

Here, in late 1939, we see the embryonic efforts of Cole to draw realistically. After a year or two of this, he doffed the "realistic" straightjacket and unleashed his glorious natural cartooning ability in the work of the 1940's.

Although the draftsmanship is crude, the story displays Cole's solid sense of graphic design, and has some remarkable panels, such as page 4, panel 6, which almost looks like a woodcut. Perhaps more astutely, however, one can compare the art and tone in this story to the hard-boiled art of Chester Gould in Dick Tracy, a likely influence on Jack Cole.

Perhaps Cole (or his editor) thought the assertion that the stories were true would help attract readers. It's certainly a formula used to great success in other instances, including Biro and Wood's Crime Does Not Pay comics. In this story, Cole begins by assuring us the story is taken from records and photographs in "Cleveland police files." Cole, who was cranking out comic pages to survive in New York City, probably did not journey to a Cleveland police station to research the story. More likely, Jack Cole lifted the tale from a tabloid paper, magazine or book, or just made it up.

It's interesting that this crime story, created in 1939, takes place in 1913, making it a historical story as well. Cole went to some lengths to show the cars, horse-drawn wagons, and clothing of the period, which suggests he probably did work from photographs.

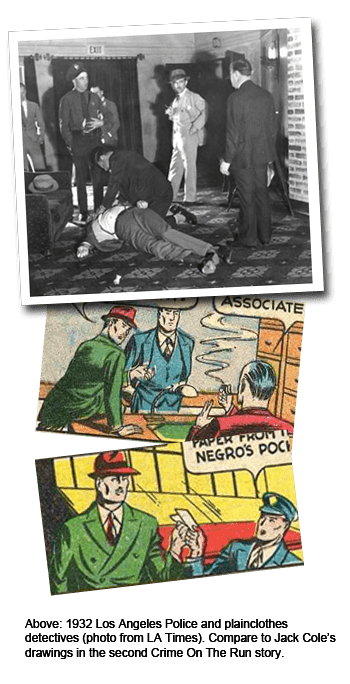

In his second and last CRIME ON THE RUN story, Jack Cole delivered a wholly engrossing and exciting story. This time, the setting is in 1932 Los Angeles. As with the first story, Cole has made an effort to capture a few period details, as shown in the 1932 LA Times photo below of an LAPD policeman and plainclothes homicide detectives. Cole got the 3-piece suit right, although he gave his policemen jackets, which appears to be incorrect, based on this photo. One of his detectives has a pencil thin mustache, just like the detective in this photo.

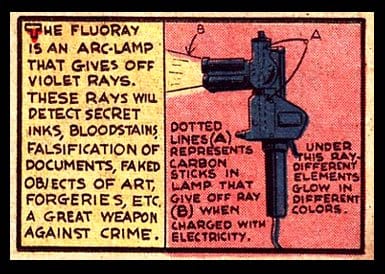

"Manhunters," Cole's 3-issue crime series for Top-Notch Comics showed crime from the lawman's point of view, complete with detailed diagrams of state-of-the-art (and sometimes made up) law enforcement technology.

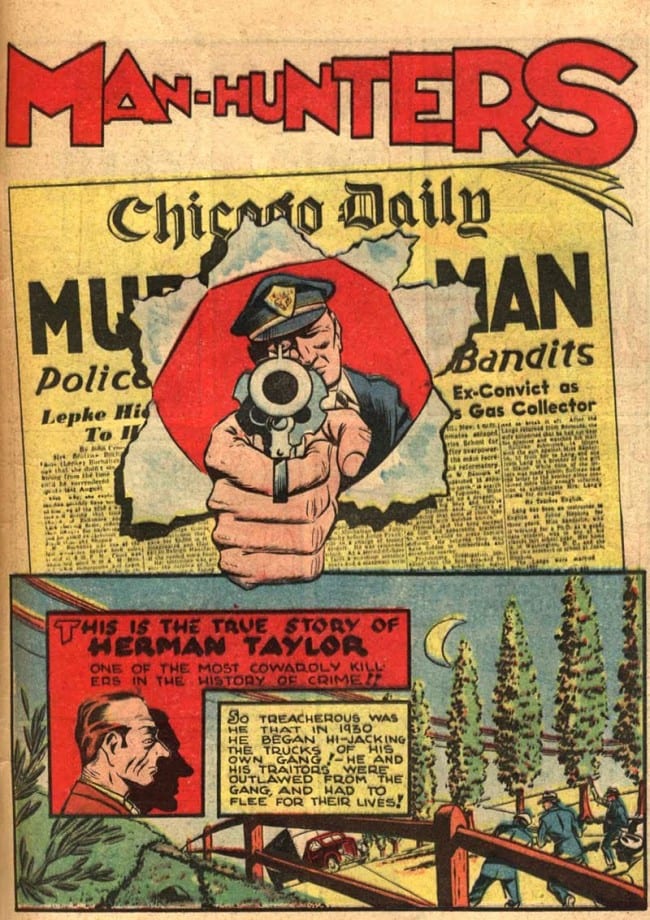

Although the draftsmanship in the stories is generally crude, Cole's solid sense of dynamic composition emerges in the eye-catching splash pages he designed for these stories.

The first "Manhunters" story climaxes with chilling scene of mob violence, introducing into Cole's comics the motif of an individual being overpowered by a crazed group. This sub-theme appears throughout his work, including his Plastic Man and Web of Evil horror stories.

In his third and last "Manhunters" story, Cole delivered his strongest splash page yet, creating an image of a policeman thrusting his gun into the reader's face, busting through the headlines of a newspaper, and also appearing to be smashing through the paper of the comic book page in a crude trompe l'oeil. It's as if the story is too powerful to be contained.

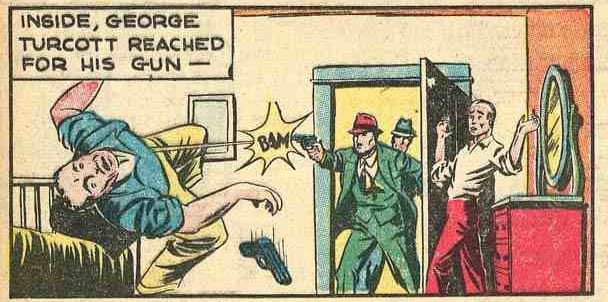

Cole's art improves with each successive story. While his rendering and inking remain crude, his sense of how to tell an exciting story using sequential pictures, dialogue, and narration becomes more assured. In the third "Manhunter" story, we can see Cole determinedly seeking ways to make his story more dynamic and powerful. One of his solutions was to draw scenes from extreme angles, heightening the emotional intensity of the scene -- a device Cole would master in his Plastic Man stories.

These stories represent Cole's first fledgling steps from short humor fillers to longer, more dramatic stories. Crime stories were already a big part of American movies and radio by 1939. The famous gangster film, Scarface, came out in 1932, and a flood of hard-boiled crime films followed in its bloody footsteps. Lucky Strike cigarettes sponsored a popular nationwide radio program in the 1930's dramatizing true life FBI cases.

Cole was perhaps slightly ahead of his time by bringing the winning combination of high-handed moralism and titillating graphic violence to comic books. Generally, the popular wave of American crime comics is considered to have begun in 1942, with the start of Crime Does Not Pay series, but Jack Cole was doing it in 1939.

The Biro/Wood Connection

It's interesting to note that Charles Biro and Bob Wood, the creators of Crime Does Not Pay, the hit comic book that spawned a spree of crime comics from 1942 to 1955, were colleagues, friends, and neighbors of Jack Cole.

Alex Kotzky, a fellow cartoonist and one of Cole's assistants related the following story Jack Cole told him to Gill Fox (see Alter Ego #12, TwoMorrows, January 2002), creating a vivid scenario that could have been lifted from the pages of Crime Does Not Pay.

One evening in 1939, a taxi pulled up to the curb of a street in lower Manhattan, New York City. Jack Cole, a tall, six-foot-three skinny man unfolded himself our of the cab, followed by his cute, diminutive high school sweetheart and wife, Dorothy, who everyone called "Dot" (an appropriate name for the spouse of the artist who created Woozy Winks, he of the eternal polka-dotted green blouse).

Their companions, a handsome man with a tough guy demeanor named Bob Wood and his girlfriend, stayed in the cab. Cole and Wood worked together, drawing comics for the Harry "A" Chesler studio. Gill Fox recounted, "Cole gets out of the cab and looks back to see Wood beating up his date."

Another time, as a result of a quarrel with his wife Dot, Cole crashed in a spare room of Bob Wood's, who lived close by with fellow Chesler artist Charles Biro. As Gerard Jones, in Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book (Basic Books, 2004) put it: "Through the walls he [Cole] could hear [Bob] Wood pounding on his girlfriend.

This troubling behavior was nothing new. Biro and Wood were unflappable womanizers, and Wood, who drank, sometimes lost control. Wood's mysogynistic violence continued unchecked, until August 27, 1958 when Wood -- ironically, the co-creator of the hit comic book series Crime Does Not Pay, confessed to a cab driver that he had beaten a woman to death after an 11-day drinking binge.

The nightmarish story of Bob Wood is where the American comic book intersects with the violent, fatalistic worlds of noir novelists Jim Thompson and David Goodis. Jack Cole was on the fringes of this desolate, pain-wracked territory. Could there possibly a connection with the fact that, three days before Bob Wood began his drinking binge that would send his companion to death and him to jail, his old buddy Jack Cole had killed himself with a shotgun blast to his head in a parked car?

In 1939, Bob Wood and Charles Biro were some of the people that the 26-year old Jack Cole, recently emigrated from a small town in Pennsylvania where he had been raised as a Methodist and a Boy Scout in a teetotaling home, had found as his new companions in the Big City. Hard working, hard living men. In other words: fellow cartoonists. It can be no coincidence that this was around the time that Jack Cole, who had drawn innocently wacky humor comics all his life, began to create grim crime sagas that depicted amoral, violent people meeting harsh justice.

In addition to the plethora of magazine gag cartoons, zany humor comics, covers,and crime stories that Jack Cole created in 1939 and 1940, he also created his first superhero stories, which are drenched with the odd, appealing mixture of Cole's humor and darkness. In the next installment of this multi-part study, we'll look at Jack Cole's first superhero comics, some of which have been "lost" for decades.

See also:

The Lost Comics of Jack Cole Part 1 (1931-1937)