From The Comics Journal #96 (March 1985).

Today, Howard Nostrand’s name is well known through the National Lampoon, and his work is seen by millions when he illustrates the Lampoon’s color comics stories (as in the April 1983 issue). But back in 1968–74, Nostrand’s unsigned contributions to comic books of the ’50s were veiled in such mystery that Nostrand’s obscurity was, in fact, a prime reason I felt compelled to interview him.

Just as Carl Barks was once labeled “The Good Artist” because readers deprived of his name needed some way of identifying him, Howard Nostrand was known during the ’50s (and later) as “The Mystery Artist” and “The Jack Davis-type Artist.” And, like Barks before his name became known, Nostrand had no realization that his work for comic books had made a lasting impression, or that his identity was, decades later, a conversational topic among comics readers.

It was, we might say, bad timing. The right talent in the wrong place at the wrong time. Entering comic books at the age of 19 as Bob Powell’s assistant in 1948, Nostrand worked anonymously alongside Powell for four years on stories for Street and Smith (Shadow Comics), Harvey Comics (Witches Tales, Black Cat Mystery, Chamber of Chills, Tomb of Terror), and other publishers. Nostrand’s forte was humor, and this was the direction he took after splitting from Powell. When the Harvey Comics Mad-imitation, Flip, began in the spring of 1954, Nostrand and Powell shared the book. By issue #2 it was evident that Nostrand’s knack for satire put Flip far ahead of the other Mad imitators of 1954. But no sooner did the still-anonymous Nostrand start to give Flip a cohesive direction by scripting the entire book (in effect, becoming a Flip editor-writer-designer, as well as lead cartoonist), than the Comics Code Authority was formed (Sept. 16, 1954), bringing the Harvey humor/horror titles to an unscheduled climax. The Comics Code served to erase Nostrand’s name from comics history. Rather than remain snarled in the starting gate, Nostrand dropped out of the race. His name still unknown to his readers, Nostrand left the comic book field (along with scores of other writers and artists).

A few years later Nostrand’s signature and byline appeared in newspapers when he began his 1959 Columbia Features comic strip, Bat Masterson (a spin-off of the 1958 Bat Masterson television series starring Gene Barry). Not many comics readers made the connection. One who did was Hames Ware and his letter about this in the letter column of Graphic Story Magazine #11 (Summer 1970) not only touches on the confusion Nostrand created in the ’50s (when some readers believed he actually was Jack Davis) but also indicates the conundrums and enigmatic signature fragments that masked the Mystery Artist’s true identity:

I first saw this artist’s work in an old Harvey comic I bought back in the early ’50s. I discounted Jack Davis, as the feet were not greatly out of proportion, but I was struck by the similarity. No name was signed. But, diligent as ever, I did not give up. Also in the same comic was a story drawn by Bob Powell. In a newspaper that one of the characters carried was a headline stating, “POWELL BEATS EPP IN BIG RACE.” The name Epp rang no bells, but turning back to the mystery artist, I found the name on a “VOTE FOR … ” poster in a store window. I thought I had identified my man.

Several years later, I picked up one of the many Mad magazine imitations that were popular in the ’50s. There, under art credits, were three names — Bob Powell, Howno Strand and Marvin Epp. This was the clincher, I felt, as I pored through the magazine. Sure enough, here was the Davis-like art. But, instead of seeing Epp signed to the story, I found three letters scribbled across the work: “NOS.” No matter how I looked at them, those letters just could not come out Epp.

Again several years passed, and I am now reading an out-of-state newspaper’s comic section when I see a comic strip with the Jack Davis-like art. The strip is Bat Masterson, and the artist’s byline reads, “By Howard Nostrand.”

Howard Nostrand — Howno Strand — “NOS”?

When I got back home, I looked up the old Harvey comic and found that the store in which the “VOTE FOR EPP” poster was displayed was named “Nostrand’s.” At last, I felt that another mystery was solved.

The only rub was that in the Bat Masterson comic strip, barely visible on a wanted poster tacked to a tree, were the words “WANTED — Marvin Epp.”

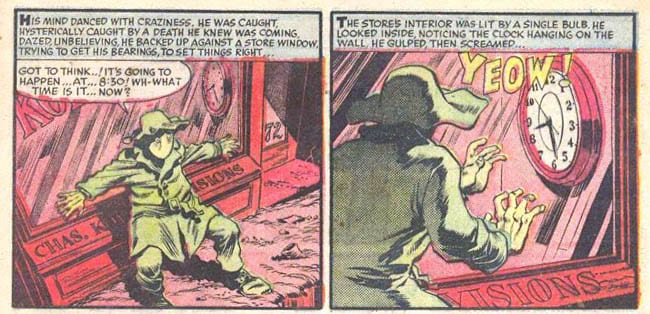

In the mid ’60s, when I first learned Nostrand’s name, I would have just mentally catalogued it under “Comics/Subhead: Mystery Artist Identified,” except that, around that same time, I acquired a copy of Witches Tales #25 (June 1954) with Nostrand’s astonishing Kurtzman/Eisner homage, “What’s Happening at 8:30 P.M.”, a comics noir laden with mood and atmospherics. Shlup-shlepping through the mud comes a sad-faced humanoid character, yet with antennae and bulbous-nosed head. He is shunned as he meanders through a near-deserted city, splashing through puddles, shlepping into the night. It is 8:00 pm. He meets a friendly stranger who expresses defeat and warns him to get out before 8:30. Instead, still perplexed but now fearful, he continues his slow pace through the city. At 8:10, seeing others fleeing, he panics, runs, crashes into an ashcan, and veers into a dead end. Arriving hysterical at a storefront, where he spots the time — 8:30 — on a clock inside the store, he experiences a moment of self-awareness only a split second before he is burned alive by a scorching stream that pours down on him from above. By ignoring the closing explanatory punchline captions (“He was a germ! And the streaks were … all-consuming … all-powerful … X-rays!”), the story can be read as pure fantasy, a foray into back alleys where Eisner never ventured, while also recalling Buster Keaton’s dramatic pantomime in Film (1965) by Samuel Beckett. Like Keaton in Film, the isolated and alienated characters of “8:30 P.M.” are mainly shown in views of their backs. There are several other fascinating parallels with Film, a 22-minute, black-and-white short directed by Alan Schneider. Film attempted to show two different “visions” of reality by intercutting subjective camera shots with objective shots: an all-perceiving “eye” (E) observes an object, while the object (O) observes his environment. O (Keaton), aware he is being perceived by E (the camara), covers his face with a handkerchief and flees through the streets, trying to escape this and all other perceptions (some imagined). In the closing scene, as E maneuvers to face him directly, O’s efforts fail. O cannot rid himself of self-perception, much as the “8:30” character, in the next-to-last panel, “realized what was happening … and what he was …”

In his notes, Beckett described: “Climate of film comic and unreal. O should invite laughter throughout by his way of moving. Unreality of street scene.” In the same fashion Nostrand avoided a “straight” style and chose to give “8:30” an appeal through the “Mad-style,” Beckett and Schneider sought a similar stylization by the casting of a comedian, as described in 1969 by Schneider:

From the beginning, in keeping with Sam’s feeling that the film should possess a slightly stylized comic reality akin to that of a silent movie, we thought in terms of Chaplin or Zero Mostel for O. Chaplin, as we expected, was totally inaccessible; Mostel, unavailable. We hit upon Jackie MacGowran, a favorite of both Beckett and me. Jackie is a delicious comedian and had been an inveterate performer of Beckett’s plays in England and Ireland … Jackie got a feature film which made his summer availability dangerously tight … Sam reacted to all developments with characteristic resilience and understanding. During a transatlantic call one day (as I remember) he shattered our desperation over the sudden casting crisis by calmly suggesting Buster Keaton. Was Buster still alive and well? (He was.) How would he react to acting in Beckett material? (He’d been offered the part of Lucky in the original American Godot some years back, and had turned it down.) Would this turn out to be a Keaton film rather than a Beckett film? (Sam wasn’t worrying about that.)

In “8:30,” everyone but the central character seems to know “what’s happening.” In Film, while O is running from E, E has direct camera close-up confrontations with other people (who express the “agony of perceivedness”). Beckett’s six-page outline called for a setting of “Period: about 1929 … small factory district,” and the exterior locations were shot in lower Manhattan near the Brooklyn Bridge, where Schneider had the streets watered down. The “8:30” character and Keaton are costumed almost identically in hat and trench coat, and just before the denouement, both Schneider and Nostrand (page four, last panel) employed full-front angles with hats causing shadows over the faces. In the opening shots of Film Keaton is introduced in right profile. With his hat, coat and handkerchief-covered face, he bears an astounding resemblance to the character in Nostrand’s splash panel — seen in right profile with a shadow-covered face.

In its sympathetic depiction of this fantasy creature’s amnesiac dilemma, tightly rendered in the stylistics of the comic book greats, “8:30 P.M.” stands apart from other comic book stories of the period. It cannot be pigeonholed, filed away, and forgotten. While dozens of stories in the Harvey horror books conjure up no fantasies whatsoever, only the desperate reality of human beings hacking away with pens and brushes in a slapdash struggle to pick up checks before the weekend, “8:30 P.M.” suggests a completely different image: an abandoned theater, closed and shuttered, yet with sets still standing after a successful long-run Eisner production has departed — and then a solitary work light flicked on so a small experimental theater group, the Howno Strand Workshop, can step quietly out of the wings for a one-night performance amid the Eisner sets. Intensifying this effect is the unrealistic coloring — all the characters are yellow, wearing pale green costumes, seen against the city backgrounds of only bloody reds and fleshy pinks.

As a humorist working in an Eisneresque mode, Nostrand was obviously given a high-voltage jolt by the early issues of Mad. One can almost see the gears and cogs clicking into place in his 23-year-old head. It was, we might say, good timing. The right talent in the right place at the right time: when Nostrand skipped out of the Powell studio in March 1952, he began his solo career in the very same season Kurtzman was hatching Mad #1 (Oct. 1952–Nov. 1952). Kurtzman’s original idea for Mad was to parody types of comic book stories (horror, SF, romance, sports, crime, etc.); his revamp of that concept into direct satires on specific radio/TV/comics/movies came later, with issues #3 through #8 making this transition throughout 1953. The revolutionary Mad feature of contemporary movie satires with recognizable caricatured likenesses, timed to coincide with the film’s general release nationwide, did not happen until Mad #9 (Feb. 1954–March 1954) with “Hah! Noon!” — followed by others in 1954 (“From Eternity Back to Here,” “Wild Vi,” “Julius Caesar,” “Stalag 18”). After 30 years of Mad, it becomes almost impossible to explain why it was so exciting and so much fun in 1954. There just had never been anything like it. Opening an issue in a newsstand was like … was like …

Okay. Forget the analogies. Lemme put it this way: You’re in a small American town. Some people there have TV sets. You don’t. So you can’t even see Sid Caesar. Your high school reading assignment is deadly — Alexander Pope (1688–1744), right? The teacher calls him a satirist, but no one laughs. School’s out. You buy Mad #12 and read — in color — “From Eternity Back to Here.” You think about the Life photo of James Jones leaning on his manuscript, pages stacked almost to his own height. A month later From Here to Eternity — in black and white — arrives at the town’s only movie theater. After seeing it you reread the Mad parody to relish the specificities. So then you spend part of the summer reading the entire James Jones novel and wind up knowing Prewitt as if he were a personal friend. Then you reread the Mad parody again. See? There was more to Mad than Mad itself. Cultural reverb, that’s what it was. Can you dig it? Well, forget it, man, it can’t be explained. You had to be there.

Nostrand was there. In fact, he was there first, so eager to get going that he anticipated Kurtzman’s evolving concept before Kurtzman, as noted in John Benson’s chronological critique of the Harvey horrors and Nostrand’s brief Harvey career:

In Witches Tales #14 (September 1952) a story, “The Devil’s Own,” appeared, which, although it was from the Powell shop, was illustrated more by Nostrand than Powell. Shortly after this Nostrand began to appear on his own (or occasionally collaborating with an artist other than Powell). At first his work seemed unsure, with somewhat stiff figures and an emphasis on heavy outlines. Then he fell heavily under the influence of EC and Mad, patterning his layouts after Harvey Kurtzman, and creating pictures that looked like an uncanny amalgam of Jack Davis and Wally Wood. At times, he even did pastiches of particular EC stories. His “What’s Happening at 8:30 P.M.?” (WT #25) draws heavily on Kurtzman and Wood’s “V-Vampires” (Mad #3), for example. When Nostrand did this, however, he never “swiped” cold but always created completely new pictures. At other times, Nostrand would lay out a story in Eisner style. In one story a rain-soaked “Dead End” sign straight out of The Spirit fills the splash panel and also serves as the title for the. story (WT #21). Other Eisner gimmicks are seen in “The Undertaker” (WT #24), where the title of the story is a reflection on the wall.

Though nearly all of Nostrand’s storytelling, drawing and rendering techniques were directly borrowed from others, the amazing thing was that because he loved and understood what he was borrowing and because he himself was talented, he created something that was almost as good as the work of those he borrowed from. Only in the writing did he fall down. The scripts, whether they were his or by others, were usually slight material that undercut his great facility in the comics form. Nostrand’s undeserved status of being almost completely unknown is due partly to his not having signed his comics work, and also to the fact that the 35 or so stories (and numerous one-pagers) he did for these horror titles represent more than half of his total output for comics. Most of his other work is in other Harvey titles of the same period: their 3-D and war books, Ripley’s Believe It or Not and Flip, which was generally masterminded and written by Nostrand and was far and away the best of the Mad comics imitations. Nostrand also did a few stories for Timely/Atlas. Many stories by other Davis imitators have been attributed to Nostrand by comics dealers and the Price Guide — including one comic actually by Davis himself!

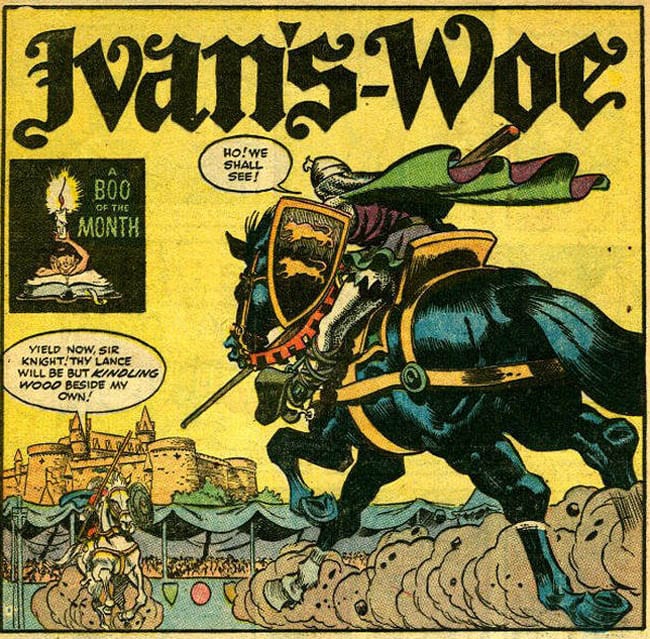

In issues cover-dated March 1954, Harvey announced a new policy. Each title would have a theme: Black Cat Mystery would feature “real-life” horror; Chamber of Chills, supernatural horror; Tomb of Terror, science fiction horror; and Witches Tales, funny horror. Yes, Mad’s influence was strongly felt. Actually, Nostrand had unofficially inaugurated funny horror six months earlier in Tomb of Terror #20 with a “Boo of the Month” series, which continued every other month until the end (switching to Witches Tales when it became the official “funny” book). The stories in the series were: “Noah’s Arg-h,” Nostrand (ToT #10); “Rift of the Maggis,” Nostrand (ToT #11); “Don Coyote,” Powell (ToT #12), with lots of funny signs on the walls à la the popular perception of Mad; “Ivan’s Woe,” Nostrand, (WT #23), the famous pastiche of Wood’s “Trial by Arms”; “Eye Eye, Sir,” Sid Check (WT #24), a private-eye parody not specifically identified as part of the series; “Mutiny on the Boundary,” Powell (WT #24); “Ali Barber and the Forty Thieves,” Powell (WT #25); and “Withering Heights” (WT #26).

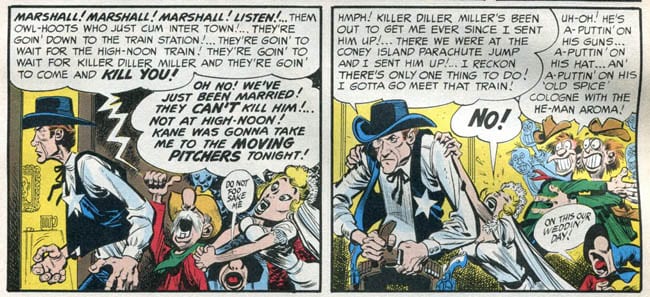

The companion feature to “Boo of the Month” was the “Silver Scream” series, which appeared every month in Black Cat Mystery: “Low Noon,” Nostrand (#47); “Les Miserables,” Manny Stallman (#48); “The Three Musketers,” Nostrand (#49); “Moe Gambo,” Powell (#50); and “Come Back Bathsheba,” Nostrand (#51). The amazing thing about these series of parodies is how fast Nostrand caught on to the possibilities of the Mad approach. When he was working on his first “Boo of the Month” he could only have seen Mad through issue #3. Nostrand’s “Low Noon” parodied the specific plot of a specific current movie, parodied the soundtrack, and used illustrational-type caricatures of the film’s stars of the kind that Davis and Wood would later make famous. Nostrand did all this about four months before Kurtzman did! Coincidentally (Kurtzman couldn’t have seen Nostrand’s story), Kurtzman picked the same film to do these things for the first time. Even though Nostrand had the early generalized Mad parodies to inspire him, and even though Kurtzman’s script for his “Hah! Noon” is about 50 times better than Nostrand’s, it’s still uncanny to realize that Nostrand actually used the definitive Mad approach and look before Kurtzman did.

Specificity in early Mad can be traced as follows: In Mad #1 the genre parodies (Western, crime, SF, horror) include Wood’s “Blobs,” a satire on the EC SF books which can also be read as a satire on E.M. Forster’s famed short story “The Machine Stops” (1909). Real-life personalities were introduced in #2 as characters in the Davis horror-baseball tale “Hex,” but John Severin barely hinted at the caricature possibilities in “Melvin,” Mad’s first parody of a specific media creation (Tarzan). Beau Geste (1924) was the point of departure for Severin’s “Sheik of Araby” in #3; while Davis played off the familiar movie serial/comic strip/comic book/radio image of The Lone Ranger, Bill Elder did not caricature Jack Webb and Ben Alexander for his “Dragged Net” (suggesting this was actually a satire on the NBC radio show, which began in 1949, rather than the 1952 TV show).

Without reference to the art styles of the originals, #4 introduced well-known comic book/radio/movie serial characters in lampoon form — “Superduperman” (with a considerably altered subsidiary character, Captain Marbles) and “Shadow” (same name but drastically changed in appearance). Mad #5 experimented with media overlaps: While “Black and Blue Hawks” is specific, “Outer Sanctum” combined radio’s Inner Sanctum with “The Heap” from Airboy Comics; “Kane Keen, Private Eye” gave a Cuisinart slicing of the titles from both radio’s Mister Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons and radio/TV’s Martin Kane, Private Eye (but with a narrative style that borrowed more from Mike Hammer and Sam Spade); “Miltie of the Mounties” refers more to the northwest genre than specifics of the 1935 King of the Royal Mounted comic strip, the 1942 movie serial King of the Mounties or radio’s highly popular Challenge of the Yukon.

Along with “Teddy and the Pirates,” #6 brought back “Melvin of the Apes” (this time with more familiar and specific Edgar Rice Burroughs bits), while Elder’s “Ping Pong” caught the plot but not the actors of King Kong. Along with a Classics Illustrated-type “Treasure Island” (Severin) and “Smilin’ Melvin,” #7 featured Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce-like characters starring in “Shermlock Shomes.” By this point, Wood was fully established as the resident comic strip/comic book satirist, but the look of these were always brushed Wood-style rather than in the styles of the originals.

Mad #8 brought back the Davis “Lone Stranger”; the Mad interpretations of Frankenstein and Batman were scripted with plot specifics but the art was cartooned rather than caricatured. Finally, in #9, came “Hah! Noon!” with caricatures of Cooper and others. It arrived at the same time EC launched its own Mad imitation, Panic (Feb. 1954–March 1954), a scant month before Flip hit the stands. With #10 (when Mad went monthly) Elder’s “Woman Wonder” bore a striking resemblance to the DC character, but Severin’s sketchy likenesses of Shane characters dulled the impact of “Sane.” (As the Mad style was defined, issue by issue, Severin began to appear increasingly ill-suited. “Sane” was his last contribution to Mad comics.)

Then the caricatured concept took off: The Panic #2 lead featured on-target Wood caricatures of Bogart and Hepburn in “African Scream” — while Mad #11, that same month, offered its second “Dragged Net” parody, this time with a heavy concentration on all the Dragnet conventions, plus close-ups and emphasis on caricatures of Webb and Alexander (suggesting that Kurtzman and Elder had finally purchased television sets). From here it was only a half-skip to Mad’s string of movie/TV parodies, faithfully caricatured by Wood and Davis, and comics parodies, faithfully duplicated in every detail by Elder.

Thumbing through these back issues, then and now, I’ve sometimes wondered what certain stories would have looked like drawn by other artists. Such a “what if” session is, to use Nostrand’s word, “funsies.” What if Al Williamson had illustrated “Flesh Garden”? What if George Evans’s aeroplane expertise had taken “Smilin’ Melvin” to a different altitude? What if “Robinson Crusoe” had been Wolvertooned? What if Frazetta had handled “Melvin of the Apes”? What if Johnny Craig had inked “Ganefs” as a cartoon noir? What if Krigstein had revived a turn-of-the-century look for “Casey at the Bat”? What if Wood had jazzed up “Bop Jokes” and “Plastic Sam”? But mainly I wonder what if Kurtzman had hired Nostrand in March 1952? Goodbye, Bob Powell. Hello, Harvey. If — ah, the Big If — yes, if this had happened, the original Wood/Severin/Elder/Davis Mad line-up would have been Wood/Nostrand/Davis/Elder, brushes blazing as all four competed to out-cartoon each other, with Nostrand stuck in the middle to form a stylistic link between Wood and Davis. Potrzebie!

All that hoohah, all that long-ago laughter of Kurtzman’s Original Marching Cartoon Jass Band, tootling “What fools these mortals be,” echoing through the tunnel of years, echoing down below Astor Place past the Puck Building all the way back to 255 Lafayette, where the saints, where the Cartoon Saints go marchin’ in, go marchin’ in.

So now picture me in the winter of 1967–68, sitting with the Wizard King of the Cartoon Saints, Wally Wood, grinning his Woody grin and chuckling his Woody chuckle as, without any prior discussion, he pulled open a suspension file and hauled out tearsheets of “Ivan’s-Woe,” Nostrand’s parody of Wood’s “Trial by Arms” (Two-Fisted Tales #34). Nostrand, for some reason, had the notion that Wood was not happy about “Ivan’s-Woe,” but my memory is that Woody was flattered and pleased by the obvious homage. This was obvious not only in the art but in the opening line with bold italics emphasizing Wood’s name: “Yield now. Sir Knight! Thy lance will be but kindling wood beside my own!”)

When Woody introduced me to Wayne Wright Howard in 1967, it was pretty clear that he was impressed by the 18-year-old Wayne Howard’s Wood-like reflected highlights and other brush effects. During his senior year of high school, Wayne Howard had won the National Scholastic Press Association’s Best Student Cartoonist Award and, throughout the late ’60s and early ’70s, he continued to use Woodwork as a model while he whipped out pages for DC, Marvel and Charlton. Wood was fascinated by the efforts of Howard and the other artists who emulated him. And the closer they got, the more intrigued he became. So, naturally, he was still somewhat amazed, 13 years later, by the work that went into Nostrand’s “Ivan’s-Woe.” He knew that it was work, not any kind of a rip-off, and he perceived that it was a genuine homage, not a mockery.

I remember standing in the center of the Wood Studio as he handed me the torn Witches Tales page of Nostrand’s nine-panel pantomime joust and mace combat. I remember him standing behind my right shoulder, pointing at the panels, indicating how Nostrand had duplicated the “Trial by Arms” layout and the story situation carrying the combatants from horses to the ground. And mainly I remember his delight at the fact that Nostrand had not copied the combat sequence but had redrawn all the figures (with two or three exceptions) into completely new poses, setting up totally different angles, yet still maintaining a faithful simulation of the Wood look. And I also remember that at that moment I asked the only logical question.

“Did you ever meet Nostrand?”

“No.”

No? I was dumbfounded. Perhaps I had naively thought such a pastiche and the mutual respect of these two men would have brought them together. Surely in 13 years? But no, never. They had only met on paper. I left the Wood Studio that day thinking that this guy Nostrand, whoever the hell he was, had picked, even if unconsciously, an apt metaphor: the two combatants could have been Wood and Nostrand jousting it out (“CLANG! CRACK! KLONG!”) with brushes and egos instead of lances and mace. After learning that even Wood did not know anything about Nostrand, the Mystery Artist seemed to be even more of a mystery. Who was he? If he had no connection whatsoever with Wood or EC, why had he consciously produced such work?

Continued