Pity the artist who has to follow up a mega-successful, critically acclaimed, game-changing work. Sure, having achieved such incredible success in the first place mitigates any desire to throw a pity party, but it's an unenviable task all the same.

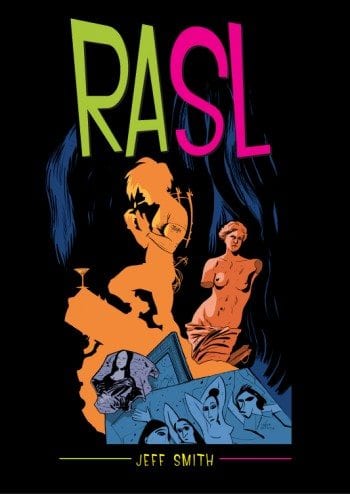

If Jeff Smith felt any pressure putting together a follow-up to the phenomenon known as Bone, he doesn't let it show. While RASL, his noir-tinged, sci-fi saga differs in tone and content from Bone, the change stems from an artist following his own interests, as Smith notes below, rather than from any direct and deliberate attempt to shift away from what he's best known for.

If Jeff Smith felt any pressure putting together a follow-up to the phenomenon known as Bone, he doesn't let it show. While RASL, his noir-tinged, sci-fi saga differs in tone and content from Bone, the change stems from an artist following his own interests, as Smith notes below, rather than from any direct and deliberate attempt to shift away from what he's best known for.

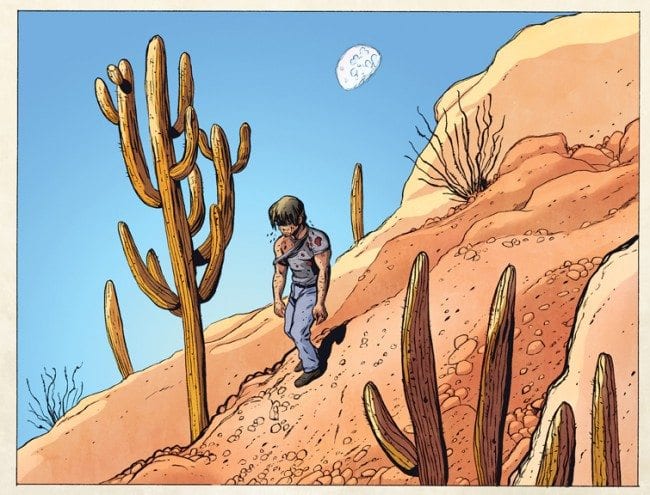

After being serialized over the past few years in a number of different formats, RASL is now available in a chunky hardcover edition, in full color to boot. Smith said he considers this the definitive edition of the work, and the subdued, muted palette does give the comic an added vibrancy. Certainly Smith's gritty, trippy story of parallel universes, metaphysics, government conspiracies, and vast Arizona vistas serves as a reminder of what a consummate and considered cartoonist he is.

I cornered Smith at this year's Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Md., almost immediately after his Q&A panel. We found a quiet spot on the lower level and while my daughter read comics, I peppered Smith with questions about RASL and comics culture in general.

Chris Mautner: What was the last SPX you attended?

Jeff Smith: The last one was 2008. So it’s been about four years since I’ve been here. I went to the first SPX and I went to all of them from whenever they started in 1994 or so to about 2001 or 2002. Back then we used to have a one-day show on Saturday, and on Sunday we’d have a pig roast and we’d play softball against Diamond. It was much smaller. It was a crazier event in some ways.

Looking around at the show today, how has SPX changed, and how is that change emblematic of what’s happened in comics in general?

Well, my goodness. My first reaction when I came through the lobby last night was, “Oh my god, look at all these people I don’t know!” And they’re all 12! They’re obviously not 12, but to someone my age, anyone in their twenties looks so fresh-faced.

One of the biggest differences is for so many of these people it just doesn’t even occur to them that they shouldn’t do comics. It’s a totally normal career choice: “I’m going to make comics.” For boys and girls. It’s so different in tone, and the energy level is off the hook. I’m excited by it. I’m wound up by it.

To what extent was RASL a conscious shift away for you from Bone and its success? How much of it consisted of you being interested in noir and sci-fi and how much of it was you wanting to do something markedly different from Bone in tone?

It was not a conscious decision at all to move away from Bone. As I was explaining on the panel just now, when I first came up with the concept for RASL, it was four years before I finished Bone. In 2000, Bone was not a children’s book yet. I was just thinking, “I did this comedy-adventure book and now I’m going to do a more hardcore sci-fi book.” It didn’t even occur to me that the audiences would be different. But the audiences have changed so drastically in the last fifteen years. The reality was that when I finally did RASL there were kids reading comics again and Bone was considered a children’s book. By that point I had to deal with the fact that the audience was going to have different expectations from me. But it was too late! It was the story I wanted to do and I’m doing it [laughs].

I just don’t think that it’s that different a story. I get that it is, and I see how people think it is, but for me it didn’t change my thinking that much. For me, it was exciting to try to learn the tropes of a different kind of story. And it was hard to get out from under Bone’s shadow. I spent so much time on [Bone]. It was a little break.

So in that sense did RASL afford you a chance to shift your focus?

Maybe that is what it was. I think I was hopeful I would be able to do something again. It was enjoyable for me to do something that wasn’t the same thing I had been doing for twelve years. Does that make sense?

That makes a lot of sense. You were talking [in the panel] about how you were doing more horizontal panels [for RASL]. Other than that, were there any other deliberate stylistic ways you tried to make RASL different from Bone?

There are a couple. The one you just mentioned was to deliberately do a different kind of panel layout, one I thought would be more appropriate for this kind of story. I don’t know exactly why, except that I was doing a different kind of action, and I thought [more horizontal panels] would speed things up and also pull each image out a little further in your peripheral vision.

There are a couple. The one you just mentioned was to deliberately do a different kind of panel layout, one I thought would be more appropriate for this kind of story. I don’t know exactly why, except that I was doing a different kind of action, and I thought [more horizontal panels] would speed things up and also pull each image out a little further in your peripheral vision.

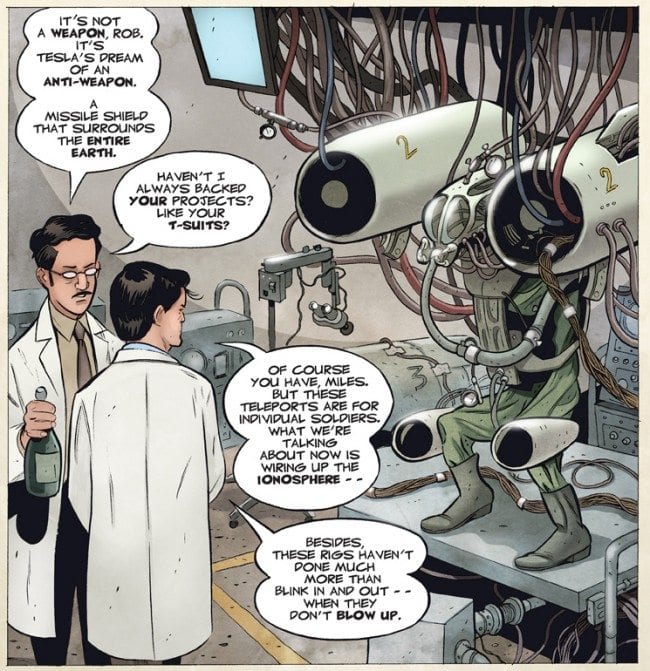

There are these little moments of meditation on Nikola Tesla that are very different than anything I did in Bone. They’re not flashbacks per se but RASL’s interior workings. It’s him working through his memories of Tesla’s story. It’s a very different style. I didn’t treat Tesla as a character in the book. You don’t see him walking around his lab talking to people. I treated it more like a documentary. My Italian publisher hit the nail on the head when he said, “What you’re doing with the Tesla meditations, it’s where Herman Melville writes about the whale’s head for no reason for five pages.”

One thing I noticed that’s different is that Bone is pretty much a straightforward narrative from beginning to end, and in RASL you’re jumping around in time a lot. There are a lot more flashbacks, there’s a lot more work for the reader in terms of keeping track – not just of the characters – but of where we are in the story. Can you talk a little about that?

It was because the nature of the story was parallel universes and also noir, which has a lot of history of mazes. The maze of the city. The maze of the lies you’ve woven around yourself. So I thought it tied in stylistically with the concept of him being lost in a maze and parallel universes to keep the reader a little disoriented, especially at first. I never said what city they were in. I wanted you to feel a little disoriented or at least not know exactly where you were and what was going on. And then slowly I stared letting you know they’re in Tucson and the Sonora Desert.

The other reason was hard-boiled stories are [told in] first person. Which is very different from what I did in Bone. Bone was a straightforward adventure story where you could go from what Phone Bone and Thorn were doing over to what Smiley Bone and Phoney Bone were up to. Or you could jump to the bad guys up in the mountains. You could hear them plotting and figure out what they’re doing. Whereas in this kind of a hard-boiled story, you only know what the protagonist knows.

And that makes for a more insular story.

It creates a very claustrophobic situation for the reader, and for the writer as well. It was a little hard, cause you have to figure out how he’s going to find out everything you need the reader to know. You really find yourself twisted up in knots sometimes.

You’ve talked a lot about how your interest in noir and sci-fi led to RASL, but there are also themes of mythology, religion, and faith that run through the book. There’s the lizard-faced villain that’s coming from a specific religious perspective, for example. And the Southwestern Native American mythology seems to be a strong motif.

You’ve talked a lot about how your interest in noir and sci-fi led to RASL, but there are also themes of mythology, religion, and faith that run through the book. There’s the lizard-faced villain that’s coming from a specific religious perspective, for example. And the Southwestern Native American mythology seems to be a strong motif.

There were similar themes in Bone as well. It’s what interests me in writing: Exploring things you can’t see or the life forces that surround us and interact with us. With RASL, the parallel universes obviously suggest that we cannot see everything. That opened up the whole idea where I could start talking about the symbolism used by the Indians of the Southwest, which I was able to overlap with the maze idea. The American Indians of the Southwest, all these different cultures and tribes, they all used this man in the maze concept. I just took that maze concept and introduced it into the story. The maze itself stands for Follow the maze and every time you reach a turning point, it’s like a life choice or life event has passed, and the closer you get to the center, the faster and faster the turning points come. It all just overlaps so perfectly with [RASL’s] maze of parallel universes and bad life choices.

You said early on, when the first issue came out, how you wanted to create a character that made bad choices and was almost unlikeable. Did that change? Did your initial conception of the book alter?

In some ways it has to. When you serialize a book – and I always write the ending, so the ending is the same ending that I always intended. Some of the major plot points were always going to happen. Thing present themselves – I can’t think of an example off the top of my head, but I did it with Bone as well, where an opportunity or something interesting pops up and I follow it. And I just try to keep it under control so it fits in with the story and I can get [the characters] back [to where they need to be]. There’s a moment at the end of RASL where there’s a bunch of birds falling out of the sky. It’s a huge, mass bird die-off. I only learned in the middle of writing the book that it was tied into conspiracy theories about the antennae ray and Tesla, which my fictional St. George Ray is based on. And so if I learn those things I can add them into the story. You have to be quick on your feet.

So were you researching the whole time you were working on the book?

Constantly. It did grow. The personal stories got a little bigger. I don’t think I had originally fleshed out the relationship between RASL and his partner that much but once the Nikola Tesla thing really kicked in and became part of the book it became something for those two characters to share and have a past about it. And that opened up different things to write about.

Why did you decide to set this in the Southwest? Because usually when you think of noir, you think of Southern California or urban areas. Or when you think of sci-fi you think of futuristic cities and other worlds. But RASL is set in a very specific and different place and time.

I think my idea was that when you boil down noir what the most important thing was a man against himself. His decisions or his choices he had to make to save himself. He had to survive and it’s a really primitive situation. That’s how I boiled it down. I thought putting it in the desert would be the perfect place for that, because once you’re in the desert there’s no one to help you. Symbolically, that’s him against nature, against himself, and it enables him to figure out a way out of [things].

And it enables you to tie in not just the Native American mythology, but also things like Area 51 and government conspiracies …

Yeah, Raytheon is out in Tucson. Plus, those cacti are in our psyches. We know that stuff. That means the old west. Mano a mano. And that’s the kind of tale I’m telling. Which is very different than Bone.

I wanted to ask about the coloring in RASL. I think you initially planned to have this in color?

Maybe I did. I could have. I went back and forth on it. It was a decision that had to be made at some point. I thought it worked pretty well in black and white; it’s a noir, Maltese Falcon story. Black and white would have been fine. Steve Hamaker, who colored it with me, we thought if we could find a palette that really worked, that didn’t just color it for the sake of it but actually gave the story more power and made the world a little more [real] – I was definitely interested in doing that. There were things about RASL I couldn’t really communicate in black and white and that was some of the reflected light and some of the crazy light things you can do with color that I thought would be better. I mean, you can do a lot with black and white. Look at Will Eisner. But there were light things I wanted to do with color and Steve found it. He found some textures and a palette that I thought ended up being very rich and dark and smoky. It works for me. It isn’t just a color version. This is the definitive version. I actually like this better than the black and white.

Smokey is a good adjective. It has a subdued feel to it.

And let me tell you, getting that to work on this toothy pulpy paper we picked was crazy difficult. We were working with our printer in Singapore and they not able to communicate to us what the dot gain on this grade of paper was and we were really sweating it. We went panel by panel making educated guesses on it, we’re doing math to figure out how much magenta or cyan to put under the black or, “That’s a guy we might need to lighten that up by thirty percent.” Crazy things. We were just guessing! I definitely had some sleepless nights waiting for this book to come back from the printer.

When you started RASL you had a couple different publishing things going. You had the pamphlet, you had the oversized collections and you had the pocket collections. Why so many different versions? What worked, what didn’t work and what did you take away from that experience?

The reason we did more than one version, quite honestly, is that RASL didn’t get a lot of traction after the initial burst of publicity that “The Bone guy is going to do something new!” It was not really taking, I could tell. So we got the first oversized trade out, that was the size I wanted to do it in, but again, I didn’t really feel like it was getting traction. I didn’t hear it being talked about or hardly even being reviewed.

This is one of the advantages of being a self-publisher: You can move fast on your feet. You don’t have to give up. I don’t have to ask anyone’s permission to fix it. So we thought maybe that first trade has 115 pages in it but it might not be enough of the story. Maybe we should have waited until we had a little more story. So that’s why we did the pocket book version, which was – it wasn’t the size we were interested in. We wanted to get two of the larger books, so we’d have double the story and see if that would catch people’s attention. And that in fact did work. We started seeing reviews and began to get a bit of traction.

I was going to ask you how you felt RASL has been received because it did seem to me that it was getting lost in the mix and I wondered if part of that wasn’t that we are in an age where people are waiting for the [completed] book.

I was going to ask you how you felt RASL has been received because it did seem to me that it was getting lost in the mix and I wondered if part of that wasn’t that we are in an age where people are waiting for the [completed] book.

That’s probably true, and I’m as much to blame as anybody for that. [laughter] The sales were decent on it as a serialized book. It started off close to 20,000 and ended up in the 12,000 range, which is enough to justify its existence. I think you can tell by the love that my team at Cartoon Books has poured into this that we hope that this is the version that will attract attention. I don’t want to sound negative. It was getting good reviews from fairly outstanding places like Publishers Weekly and newspapers. We were getting really good reviews the whole time, starred reviews from Booklist. So it was getting good critical reviews the comic book world just wasn’t …

… lighting on fire about it.

Right. Like they did with Bone. Of course, nothing’s ever going to do that.

Comics culture has become rather balkanized in recent years and there’s little overlap between the different markets – the SPX people don’t mix with the manga people, etc. I wonder if that makes it harder for certain authors to get their work out there and get attention.

It might, but I don’t think that’s the case with me. It’s always been stratified, somewhat artificially. Remember, when we were kids, if you liked Marvel you weren’t allowed to like DC. There were all these demarcations and lines in the sand that have always been there. If you like superhero comics you don’t like the non-superhero comics. Even today, in our little pocket of indie comics there are stratifications of “These are art comics and these are indie comics.” And all of that is completely made up. It makes no difference. If Dan Clowes is a brilliant cartoonist, just because of the subject matter, that shouldn’t put him into a certain strata. It’s because of his skills. It’s because of his chops.

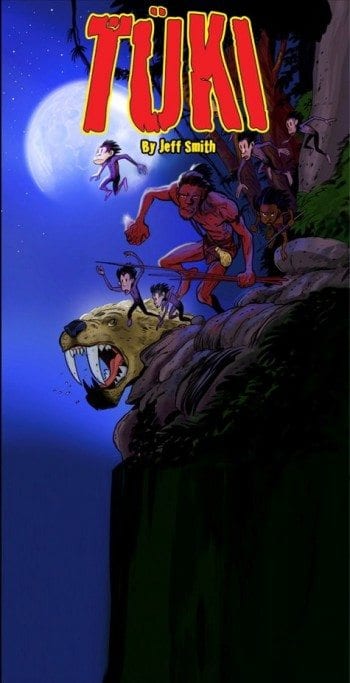

Talking about format and style, I wanted to ask about your next project, Tuki Saves the Humans. You said you’re serializing this online. What led to your decision to do that? Are you down on the pamphlet now?

Talking about format and style, I wanted to ask about your next project, Tuki Saves the Humans. You said you’re serializing this online. What led to your decision to do that? Are you down on the pamphlet now?

No, I’m not down on the pamphlet, and I don’t think print is going away, but clearly the future is digital. There’s no way you can ignore it. I haven’t seen a good model for making money online. It seems like the webcartoonists that have succeeded and are making money have somehow transitioned into the book distribution world that’s more traditional way of making money. Someone like Kate Beaton. She’s a webcomics artist but she’s making money now because she has a book and that book is going through normal channels. Faith Erin Hicks has also done a similar thing. I think that’s a good model. It seems to be working. And I just decided I want to try it. Again, I’m a self-publisher. I can experiment. And if it doesn’t work, you’ll see me turn around and try something else very quickly.

Can you summarize the story?

It’s going to be a Pleistocene-era story that takes place two million years ago when there was one of the first big ice ages. This is the one that locked all the moisture up in one of the polar ice caps. Africa is dry as a bone and all the creatures that live there, including early hominids, and all the animals, they were losing their jungle environments and were becoming extinct, including early man. At some point someone was the first one to leave Africa. There was someone who left Africa and populated the rest of the world. I want to tell that guy’s story. All the forces of Africa, the other humans, the animals and ancient gods are going to do their best to stop him.

And I have the ending written. I always write the ending before I make that first page.

Comics culture has changed so much since you started Bone, and Bone has played such a large part in that change. I feel like you have a unique perspective because you straddle so many spheres. You’re a comics guy, you’re someone who started in the traditional comics format, but you’ve been published by a book publisher, you’ve got a young adult fan base, etc. When you look at the comics industry as a whole, do you see it as healthy? What’s your take on where we stand?

I would have to say it looks pretty healthy. Especially [compared to] twenty years ago, when there were so many rules and conventionally wrong ideas about comics. First of all there were no kids reading comics. Your daughter is sitting here reading a comic right in front of us. And she’s making comics. That is healthy for us as lovers of comics, as creators of comics, as writers about comics. It couldn’t be better.

I remember very clearly the day in the late ‘90s when I noticed it wasn’t just guys in their thirties on the showroom floors. All of the sudden I began to see young couples, young girlfriends – two girlfriends holding hands and going, “I’m going to go shopping for comics.” I’m like, “What’s happening?” This is a wonderful, wonderful thing.

There were periods where early in the mid ‘90s when declarations were being made that children were lost to comics. They’re not going to read at all, they’re going to play video games and watch movies and TV. Between manga and the Scholastic books there are [now] millions of kids who want to read comics. And there’s the fact that we were able to get out of the comic book store ghetto. I love comic book stores and they still represent a large part of my audience, but we needed to be out of there.

We used to talk about comics all night, every night, all of us of that generation. All we wanted to do was get our comics read by the widest possible audience. And one of the problems, especially for those of us starting to think of this long-form format, where we were going to serialize very long stories with a literary structure and a beginning, middle and end – the problem was comics were sold like magazines. They were up on the shelf for four weeks and when the new issue came out that one went down and into a long box never to be seen again, except by a collector. Someone like me, who is writing a story that’s planned out as a 1,400-page novel – I need people to be able to read that first chapter.

In the back of Wizard it said Bone #1 was worth $300. Nobody can read it! So we had to get political about the whole thing. We would have pizza parties or meetings at Dave Sim’s penthouse suite back in the day and we’d meet with retailers, especially key retailers that were on our side and believed in us, and say, “You’ve got to stock graphic novels.” Once you sell out, buy them again! It’s like if you have a hardware store and you sell out of hammers, you get more hammers! We would explain to them, these are profit centers. You can count on these.

We had other prejudices we had to get over. Self-publishing – only in comics was it a badge of honor. Outside of comics, there were guidelines. Baker & Taylor wouldn’t touch a comic and they wouldn’t touch self-publishing. So we had all these battles.

Do you feel like those battles have been won?

Yes and no. From an actual standpoint where we were trying to get more shelf space in the stores and into [other] distribution systems into libraries and big box stores. Those were very much our goals: Wider audiences for small press, the work of an author with a voice.

In that sense, yeah, I think we did win. Because there were battles just to get out of Artist’s Alley. This show we’re at right now came out of a conversation between Dave Sim and I, where we were like, “Let’s go on the road” – cause we were like two kings for a couple of years. “Let’s go on the road,” and we contacted a bunch of good stores all around the country and … the next year [we visited] the Bethesda store. But then they started SPX and we were there.

We needed to control it cause the system that was in place was not there for us in terms of San Diego, the conventions, the stores, certainly not Barnes & Noble. So yes, in that manner, we checked [these things] off [our list] and we live in that world now. We don’t have to be that political anymore.

Still, in terms of outreach, I still meet occasional librarians that are like, “This isn’t reading. I understand why kids like graphic novels because they can do other things while they’re reading it.” What? [laughter] It’ll never be done. But that’s the new generation’s problem. Let these young turks handle it. I’m old and tired.