PETER BAGGE:

I recently ran into Chris Ware at a comic convention. Chris knew that Kim Thompson had been diagnosed with lung cancer, and was eager to know what the latest prognosis was. When I told him the grim news, that Kim had two weeks left at best, his face went ashen. After a beat, he said, “All I can think about is how much I used to fight with him.”

I couldn’t have related more to that statement. Kim was the editor and all-around point person on my comic book series Hate back in the 1990s. During that title’s ten-year run, he and I argued frequently, and over every aspect of the series you could think of. These of course were “good fights,” as my musician friend Steve Fisk calls them, in that it all stemmed from both parties being equally invested in and committed to trying to produce as strong a product as possible. We also were both incredibly stubborn and opinionated, and the fact that that we also were making Art only raised the stakes further, intensifying and personalizing our disagreements to a greater degree than they would have been otherwise. And I have no doubt that in the end our battles led to the creation of a better product.

But these disagreements also took their toll on me, and while I had many reasons for ending Hate as a regular ongoing series in 1998, I must confess that the seemingly increasing differences Kim and I were having played no small role in that decision. I was fully aware at the time that not just Fantagraphics but the entire alternative comics industry was heading in a direction, both artistically and format-wise, that I had little interest in being a part of. Yet Kim was more than happy to embrace this new direction, so what little willingness he showed in helping me pursue my own plans was at best a reluctant indulgence on his part, and it quickly took the wind out of my sails.

We of course continued to work together after that, albeit on a much more casual basis. There were the less-than-annual Hate Annuals, for one thing, as well as regular book collections of my work, both from the Hate and Neat Stuff days and elsewhere. In fact, Kim made a point of scheduling the release of some kind of “Bagge book” every calendar year, which I greatly appreciated, and in return I yielded to his editorial preferences much more than I would have in the past. Well, I trusted his instincts in general, so nothing regretful ever resulted from my yielding –- in fact, it sometimes seemed like the more I stayed out of his way the better the book would turn out -- but my sweating the small stuff would have also resulted in the petty bickering that I no longer had the stomach for.

And yes, all of this bickering I’m recounting here seems really petty to me now. Death does that to you. It humbles you, and makes you feel small and selfish. And by “you,” I of course mean “me.” Yet this is where my mind keeps going when I think of Kim: Regret, but also enormous pride for what we accomplished together. And regret for never taking stock of what we did together until now! And of what Kim did for me. Which was a lot. He and Gary Groth gave me my own title way back when I was a nobody who couldn’t even get arrested, let alone get much more than a gag panel published in the lowliest of men’s magazines. They then gave me enough creative rope to hang myself with, which thankfully I didn’t (though I came close). And they did the same with countless other independent-minded artists as well, which struck me as a miracle of sorts at the time, and still does. Hell, it is a miracle!

I wanted to say all this to Kim the two times I saw him after his diagnosis -- which I did to some degree, though I didn’t want to pile it on too much out of fear of making him feel like he was a goner (there was still a sliver of hope when I saw him, too). Still, I never thanked him anywhere near the extent that I would have liked to. So I’ll do it now. Thanks a ton, Kim.

PAUL BARESH:

I still remember the first conversation I ever had with Kim Thompson over the phone. I was answering a “help wanted” ad in The Stranger that read: “Late night scanner needed for scanning artwork. Must know Macintosh.” At the time I had no idea what Fantagraphics was and I thought Love and Rockets was a glam rock band. I envisioned the job entailed scanning large pieces of classical art style paintings on some huge scanner. My phone conversation with Kim went something like this:

KIM: The job is scanning pornography.

ME: Okay.

KIM: It pays $7.50 an hour.

ME: Okay.

KIM: That usually scares people away. Come on in for an interview.

I went in for the interview and got the gig, doing nothing but scanning Japanese Mangaerotica stats (porn comics). Eventually, when that ran out, Kim had me do other work such as comic-book lettering, page layouts, Photoshop work, and more scanning (of non-porn comic art). I’ve been working for Fantagraphics in the art department now for over twelve years, working mainly on Kim’s books, and am very thankful to Kim for bringing me aboard the Fantagraphics team as I have been very happy here and have enjoyed the work.

I must say, I would rarely see Kim in person, as I’ve always worked the “graveyard” shift, although I would occasionally see him when I’d stay late and he would come in early. We mainly communicated by e-mails, of which I would usually receive ten to twenty from Kim each day. One thing I must say about Kim is that I have always been in awe of his intellectual capabilities. The man was smart as a whip. He seemed to know everything about art, pop culture, and the proper usage of punctuation (he probably could have been an English professor), plus he spoke several languages fluently. Kim was also savvy in the technical aspects of book production. He knew all about the layouts, the printing process, all that stuff. He probably could do a lot of the production work himself if he had the time. (Gary Groth, on the other hand, often asks me what “RGB” means, although he is getting savvier.) Kim was also a “hands on” boss, as he would often get into the page layouts and enter the text and lettering edits himself. I was always in awe of how much work the man did. He would do all the proofreading on his books, often making the edits himself, and basically ran the production in the art department, on top of all the other duties he did as co-publisher of Fantagraphics. I don’t know where he found the time to do everything he did, but I assume he didn’t sleep much. As others have said, Kim would routinely (much to Gary’s chagrin, I think) interject himself into problem-solving on Gary’s books. I must say, though, that usually Kim was right! The man knew his stuff!

Besides being an all-around intellectual and champion of underground comics, Kim was also an excellent bowler. One of my fondest memories of Kim was the time I narrowly managed to beat him at the last official Fantagraphics Christmas bowling party (many years ago) after I bowled the best game of my life in an intense “winner take all” one-on-one game against Kim. A few years later I gave Kim the Fantagraphics bowling pin trophy as a Christmas gift. I think he got a kick out of that.

It was a shock to hear when Kim was diagnosed with lung cancer several months ago. I, like most others, thought he had a good chance of beating it and returning to work. It was even a bigger shock when I heard he had been taken off the treatments and it was just a matter of days. I guess it still hasn’t sunk in that Kim is gone. To say that he is missed here is an understatement. I still expect to see ten to twenty e-mails from him each night when I log into the Fantagraphics e-mail, but I guess Kim is too busy hobnobbing and discussing comics, art, and pop culture with all the other comic-book greats that have also passed on. Maybe he’s even bowling.

Here’s to you, Kim!

DAVID B.:

Kim was the kindest and most attentive of editors and to have a U.S. publisher, an American, who spoke fluent French –- what a pleasure.

From time to time we exchanged e-mails with regard to my work, which he appreciated and was the first to support in the USA, as well as with regard to the French graphic novel.

I had discovered Kim's passion for Belgian wildlife cartoonist Raymond Macherot and I suggested he put together a Macherotland in Seattle, to compete with Disneyland.

This project had not advanced too much but I hope at the moment you're reading my foolish thoughts, he is in cartoon heaven, bringing it up.

One of these days, Kim.

STEVE BRODNER:

Hearing about losing Kim hurt. We don't expect to be missing big parts of the architecture of our lives with the loss of one person. But there are key, indispensable people in our lives, the importance of whom we consider, usually, only when we have to.

How do we manage without Kim? I think we stand around kind of stunned for a while. Then comes healing, where we come together and allow new forms to emerge. For now we have grief. And thoughts. And reflection on what he was like to have with us and perhaps what some of it meant.

We worked together on my book, Freedom Fries, in 2004. This was an unusual book for Fantagraphics. Covering 25 years of political illustrations from US journalism. Personal statements made in the world of commercial art; art seen and then tossed out daily. This was to be somehow collected made into a book narrative. The reason this project worked was Kim. He had tastes and interests beyond the worlds he worked in. His bringing my book in was a statement that graphic expression is tall and wide and deep. He cradled this baby, rocked it, raised it up. He showed his smarts and great competence in many ways. You can hear the wheels turning before he would offer “an executive decision”, which was, very often, dead-on smart. The shape of the book, its coherence and focus was all the result of Kim’s decision process.

Freedom Fries was a labor of love by him, yours truly and Kelly Doe our designer. Each of us was a perfectionist to the point of absurdity. And all went well with, as you might imagine, many phone calls and emails back and forth about decisions that got tinier the closer to the deadline we got. The corrections made to the last version were not complete so there needed to be one more round. Burning the oil, we all hammered this baby out. At last the truly final version of Freedom Fries was sent to the Korean printers. Soon after, books arrived. Reading the first page revealed that the printer had accidentally used the second-to-last file. I called Kim to ask him to stop the presses. This, of course, was not possible and the book would stand or fall, typos and all. Kim consoled me with a comics-homily, "You know, in the Fantastic Four there is a villain named Doctor Doom. He goes around with a mask, thinking his face is horribly disfigured. In one episode the mask comes off and we see that he looks . . . okay! But he lives in terrible shame over a tiny imperfection." Then he paused. No further allusion to my current state of frustration was necessary. The comment was an essence gleaned by sage comics scholarship. I loved the metaphor and the way he used it. It did talk me down. I still beat myself up about such things. But Kim is still in my head talking sense to me. I am certain that for many artists and writers his wisdom, generosity and friendship live permanently in them. In this way he goes on and as we work with others on our respective projects we get to pass Kim’s gifts along.

I never got to thank him properly, which makes me extra sad. But I am sure that he occasionally looked back at his body of work and saw what he had accomplished with and for us . . . and flashed a puckish smile.

BOB BURDEN:

Kim’s passing was a shame, a real bad break. Kim was a nice guy — an ever kind and gentle soul — and it doesn’t seem at all fair. Hearing thE news brought back a lot of memories from the good old days — from the early days of this whole comic fandom subculture. Wow. And they were good memories and good times. I always saw Kim and Gary and the rest of the Fantagraphics gang at all the conventions. Conventions were a few thousand people at most back then, everyone knew everyone else and the parties could last till three or four in the morning. Kim had a certain benign smile, I remember, and I will always remember him with that smile.

I think I speak for all creators when I say that Kim and Gary’s contributions to the field of comics entertainment — back then and now — cannot be underestimated. Or taken for granted by any of us.

Fantagraphics was a port in the storm for so, so many wonderful and amazing books. Year after year, decade after decade. Besides all the wild, leading edge comics Fantagraphics published, think of all the comics that they instigated, just by their very presence. So, so many artists picked up a pen and got started, encouraged to do greatness (and forsaking crass obeisance to commercial viability) totally inspired by the kind of artistic books Kim and Gary published, and what it would mean to get reviewed in the Journal. (And to get to read that review to their peers and their Mom.)

And think of what Marvel or DC would be like without Fantagraphics.

Take a “George Bailey journey” for a minute. What would our comics medium have been like if Gary and Kim had never existed? Would DC have ever rolled out a Vertigo line? What kind of creators' rights would there be without Fantagraphics holding a mirror up to the cavalier indifference of the corporate publishers.

And isn’t it always that way? Just a few special people that make the biggest difference in any era or a movement. Whether its City Light Books or Arkham House or Mabel Dodge’s little Greenwich Village get-togethers on Sunday afternoons. Fantagraphics and the indy, artsy, alternative comics managed to keep a human face on the game, and maintain an artistic center of gravity going through all the high and low tides we survived over the years.

In the end, we were a little cottage industry and an art form, rather than a pop-culture, mass-market juggernaut. And that’s fine with me, and I can still see Kim’s smiling face, and know it was fine with him. Just the way he wanted it.

MIKE CATRON:

Editor, Publisher, Pioneer, Friend

Kim Thompson’s death rips a hole in Fantagraphics that will never fully heal.

But if you love comics, if you’re engaged in trying to make a difference in this art form that we love, or even if you just hope to do so one day, you should be happy for my friend Kim. Even a bit envious. I know I am.

Because Kim Thompson landed his dream job on his first try and got to work his whole life in comics. And the world of comics is today a better place partly for his unwavering determination to make it so.

Kim grew up outside of the U.S. because that’s where his dad’s job took the family. He settled in the U.S. for the first time at age 21 and within a very few weeks of his arrival, he was pitching in to help Gary Groth and me on The Comics Journal.

He didn’t apply for the job, exactly. He just kept showing up each day. So Gary and I kept throwing work at him. Early on, his facility with multiple languages made him a good copy editor.

He built on that talent to learn publishing from the ground up and became one of the best editors the comics community has ever known. During a period in which the market was dominated by factory comics, Kim, as editor, fought to elevate the visibility of individual artists that he truly, passionately, believed in. As the co-publisher of Fantagraphics Books, he was in a position to do something about that. It is a power that he used for good.

Kim Thompson became a pioneer in comics because, as editor and co-publisher of Fantagraphics, he invited — no, expected — no, demanded — that readers share the love, appreciate the care, and exult in the joy he felt for the comics he published — and even for many he didn’t.

Kim was justly proud of what Fantagraphics has accomplished and didn’t hesitate to say so. One of my favorite Kim quips occurred a couple of years ago on a blog discussion that was bemoaning the lackluster quality of comics reprints from a different publisher. When an anonymous poster took a swipe at Fantagraphics, Kim was there to set the record straight and lay down a little snark. The exchange looked like this:

- archive this

January 12, 2011 at 2:24 pm

What I find astounding is Fantagraphics holy reputation. We haven’t seen any of the those “90% sized” books and we already know that “Fantagraphics is set to do justice to Carl Barks”. They get a free pass for everything: reducing the size of the books, bad scans like on Prince Valiant…

- zack soto

January 12, 2011 at 11:32 pm

What? Bad scans? Tell me more. I am pretty sure those Prince Valiant books are as good as the book has looked since the first time they were printed!- kim thompson

January 12, 2011 at 3:53 pm

The Carl Barks books are NOT 90% (an off-the-cuff figure thrown out by Gary G. that has traveled around the globe five times since he made it, despite prompt attempts to rein in back in), they will be something like 97%.We get a free pass for everything because we are super awesome and have earned it.

Earned it indeed, Kim.

We mourn the loss of Kim Thompson — for what it means to Lynn, and to us, and to comics. We will miss him always. And we will love him forever.

DANIEL CLOWES:

Kim was my long-distance friend, publisher, and occasional role model for thirty years. He was one of the last people with whom I had an old-fashioned telephone relationship and we maintained a casual, gossipy rapport, fully grounded in the mutual respect one feels toward a fellow lifer (usually these calls devolved into Kim trying to convince me to give DePalma’s Snake Eyes another try, or baiting me with the assertion that Franquin is the best cartoonist of all time). He loved being the first to share the news about comics events, and it occurs to me that this is the first major industry death that I didn’t first hear about from Kim himself.

Kim and I also had a business relationship and, despite the stresses inherent to such a loaded enterprise, I grew over the years to appreciate more and more our simple, finely honed interaction. He was such an utterly reasonable man, never negotiating with exaggerated figures or lying about cash flow problems. He was up front and fair and expected the same, and if I could convince him via reasoned arguments to increase print runs or lower a cover price, he would do it without complaint, and if I couldn’t, he wouldn’t. Having this kind of gentlemanly honor-bound business relationship feels like something of the distant past and its loss isn’t something I care to ponder. Kim, among his many fine traits was honest to a fault, and one could learn a lot from analyzing the careful prudence he employed in keeping his beloved publishing house afloat and thriving.

Kim had, from my vantage, what appeared to be an enviable life: a happy home, and an unending pride in his calling. He was truly a gentle, kind soul, though he always thought of himself as a bit of a punk, I think. I don’t remember ever seeing him angry, and he treated even the lowliest of adversaries with good-natured acceptance. Dave Sim has probably lost his only sane defender. Kim knew he and Gary had done something beyond what anyone could have ever imagined and he seemed continually giddy over what turned out to be an astounding and indelible achievement.

We artists all cared deeply about what he thought of our work – in most cases, his was the first (and sometimes only!) response, and the weight it carried can’t be overstated. He was always kind, but never dishonest in his appraisal, and if he thought something was especially good, you could tell right away. He also had an endearing (and often maddening!) way – something I blame on his Scandinavian heritage – of neutralizing his compliments with a tiny, offsetting follow-up that brought the swell-headed among us back to Earth. (“Hey, congratulations on being nominated for a Harvey award. [pause] Too bad it’s only for best letterer.”) It’s that evenness of spirit that I grew most to admire. He once told me he was perfectly content with his life and couldn’t imagine what he’d do with anything more than he had. I think about that all the time.

Years ago, at the old San Diego Comic-Con, the ever-observant Gilbert Hernandez pointed out that while we always saw Gary and the other Fantagraphics guys at dinner after the con closed down for the day, we’d never see Kim. Where the hell was Kim? It became a bit of a running joke and a mystery. I think I even asked Kim once and he deflected it in a way that made it seem even more mysterious. Then, one night an unwieldy group of us were walking to some restaurant and I happened to look in the window of a Carl’s Jr. and spotted Kim, sitting by himself eating dinner with a big stack of comics he’d picked up at the show, a smile on his face. Even after spending his day, not to mention his noble and far-too-short life, toiling in the dark heart of the comics world, that’s where he chose to be.

SYLVAIN COISSARD:

During all the years I have worked with Kim (mostly on the works of Jacques Tardi, Emile Bravo and David B., which my agency had licensed to Fantagraphics), I cannot remember one single e-mail in which you would have found an aggressive attitude, spite, or even a bad mood. He was just kindness, intelligence, culture, curiosity, and brilliant ideas. All the time. The comics world is losing a man of the art who did incredible work getting French (and more generally, European) comics authors introduced overseas. I have lost a friend.

AL COLUMBIA:

I know I probably wouldn’t exist as a cartoonist if it weren’t for Kim Thompson. Kim looked out for me and bent over backwards for me since I was 23 years old and has never stopped being there since. There's never been a time Kim wasn't available for me to call to talk to if a nightmare was afoot, or to just chat, or to just listen to me be weird. He always expressed a certain unconditional friendship and support for me, like a dad, or a really cool step-dad — and as such I feel anything I can say sounds dumb compared to how I feel, except to say I loved Kim, he was family, he was one of us, and he will be missed very much.

MARK EVANIER:

Kim was a man of great humor and industry. He had a great laugh — a really great, from-the-gut laugh, the kind only found in people who love the world around them enough to find things funny.

The vast body of books of comic art he published, edited, nurtured, and otherwise midwifed testify to how good he was at all he did. The overflowing shelf of Eisner Awards also makes the point, though not as well. Check out the books themselves.

He had a passion for presenting the best material Fantagraphics could get its mitts on and presenting it in the best possible way. I knew this before Carolyn and I started working with him to bring forth the collections of Walt Kelly’s Pogo… but I don’t think I expected to like working with Kim as much as I did. He met every problem with grand spirit and you could hear the gears whirring as he tried to figure out, "Okay, how do we solve this and make the book better?" That was always his first concern. I’m not sure he even had a second concern but if he did, it was a distant second. It’s so sad to lose a guy like that. So sad.

R. FIORE:

A Life in Funland

I always say, if you believe in a transcendent deity who, once He's had his little joke, will guarantee us all an eternal life of bliss, I'm on your side, pal. Believe me, when you turn out to be right I'll be first in line to take a boot in the ass for doubting you. To be brutally honest though, lung cancer lends more weight to the Meat Machine theory than the one about the Loving God. What happens is, the body stages a revolution against itself. A dissident faction of abnormal cells rises up as if to say, "Who are you to say what is normal? Are we not tissue just like you?" These rebels have no desire to engage in such bourgeois pursuits as breathing or thinking or supporting your frame, or anything but reproducing themselves. If you're like me, as soon as you heard about Kim Thompson's diagnosis you took the Internet and found that there is absolutely nothing encouraging about this disease there. The predominant message is "Don't get your hopes up." I sent him a message expressing the hope that his cancer had made a poor career choice, that it should have been something less ambitious, like a rash. As it happened he got the Khmer Rouge of cancers.

These days you figure you have an 80-year lease. Sure, if you really trash the joint you can get evicted early, but even then you figure you can dodge the process servers until your mid-60s. Kim didn't engage in any of the typical asking-for-it behavior -- didn't smoke, avoided nuclear disasters -- but he got it anyway. It could have happened to Jonas Salk, it could have happened to Nikolae Ceausescu, as it happened it happened to Kim. Supposing though we spare ourselves our feelings and presume this fate was engineered into the machinery, that to escape it he would have had to be someone else. It is the raw deal of raw deals, but up until that shot in the head Mrs. Lincoln would have had to have been delighted by the play. It is a curious privilege of our time to have the chance at what I've always thought of as a life in Funworld. There are enough people about that your services are not required for such tasks as digging the coal or growing the food or selling the insurance. There is enough wealth about that it is possible to make a living amusing those who do the drudgery, a much more enjoyable task. I had a couple of years of Funworld and it's like a weight lifted from your back to go to work and do things you like to do, that have meaning to you. Kim never had quite that feeling because he hardly born the weight at all. The most reliable ticket into Funworld is having the talent to amuse people. If you don't you must invent a role for yourself in the service industries that surround the making of fun, which Kim managed to do. To be sure at the start whether dinner would be hot dogs depended on whether there were subscription checks in the day's mail, but at the price of early insecurity he bought himself freedom. He never had a master, for some time never wore long pants except for funerals, indeed I understand was barely clothed save for a bathrobe for extended periods. In this primordial office casual he not only made a living enjoying himself, but the result of his enjoyment was the making of tangible things that had meaning to him and that made him proud.

If he had told you 36 years ago that he would one day be the publisher of Robert Crumb, Charles Schulz, Walt Kelly, Carl Barks, Harvey Kurtzman, Will Elder, Hergé, Jacques Tardi, and EC Comics, together with much of the Mount Rushmore of a comics era yet undreamed of, you would have said, "Will this be before or after you've laid all the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders?" Even when I got there in the mid-'80s and they were still proud and happy to publish The Flames of Gyro, this would have seemed like a teenager's vain dream of glory. And yet it all came to pass. He was the Good Cop of Fantagraphics, not merely liked but well-liked. I am certain he personally deflected at least half of the ill will that the enterprise attracted, a sort of human Van Allen Belt. He was a font of industry gossip, no more malicious than the industry itself. He is not a replaceable person. Above all, creatively speaking, his loss will be a terrible blow to French comics in English. I don't know this from the French end, but I recall reading David B.'s Epileptic I was so struck with how smoothly it read that I had to check who'd translated, and saw it was Kim. Where even the best translations of comics French, up to and including the renowned work of Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge on Asterix, will come out somewhat stilted, Kim's come off as idiomatic and natural English. If you were Fantagraphics this skill was just there, like water in the tap.

So he wasted less of the limited time he had on things he didn't want to do than just about anybody I can think of, and he spent more of that limited time disseminating things we all can enjoy than just about anybody you can think of. And if he had all the time that you or I or anyone has the right to expect then somebody might hardly never not have been unsorry, perhaps.

DREW FRIEDMAN:

According to Kim Thompson, I had the honor of (indirectly) giving him what he told me was "the most thrilling moment of his career."

Kim was the brilliant editor of my last six books for Fantagraphics, including my three books of portraiture depicting "Old Jewish Comedians" (designed by Monte Beauchamp). The only running text in the books was the comedians' actual Jewish names, along with their showbiz names (for example: Benjamin Kubelsky/Jack Benny). My wife Kathy and I diligently researched the original names using various sources, mainly comedy history books and via the web. When the first book was released in late 2006, Fantagraphics sent out several copies to some of the (still living) comedians who were included, among them Mickey Freeman, Freddie Roman, and Jerry Lewis. All three aged comics instantly called me directly to tell me they were absolutely thrilled with being in the book, so much so that they arranged for a Friars Club book party to celebrate its release.

Shortly after the Friars party I received a call from a giddy Kim Thompson, his upbeat voice far from his usual steady monotone. He had just gotten off the phone with one of his all-time heroes, none other than the legendary comedian Sid Caesar of Your Show of Shows fame, now 84. Caesar had placed a call to Fantagraphics and their secretary instantly transferred the call to Kim. It soon became clear that Sid Caesar was not at all happy. Why? Because his "real" name was listed as Isaac Sidney Caesar. At the time, every Sid Caesar tribute site, including Wikipedia, claimed his real name was indeed "Isaac". He claimed it was not. He proceeded to rant, rave and kvetch into the phone at Kim for a good twenty minutes or so, as if Kim was responsible for this insult, even launching into faux German/Yiddish double-talk to overly-emphasize his points ("Vot's Vit You?? You ish a DUMMKOPF!!"). Kim was in heaven, Caesared the moment and basically sat back and let Sid Caesar perform his special brand of (angry) schtick. The more Caesar carried on, the more Kim laughed, and Caesar seemed content because he had a clearly receptive audience of one all to himself, even if it was someone who published a book that infuriated him. They somehow established a brief phone-bond, a performer pleasing his audience. He continued his raving until he eventually became exhausted and finally banged down the phone. Kim immediately called me to relate what had just transpired and told me that although he was a bit shaken, it was the most thrilling moment of his entire career AND the best part of having just turning fifty. He asked if I wanted Sid's phone number so I could also enjoy the experience of being reamed out in Yiddish by a comedy legend but I declined the offer. I was content with living vicariously through Kim's experience. Finally, Kim, always the level-headed editor, summed things up: "Well, I guess this means we won't be able to get him to write a foreword to one of our Peanuts books. Oh well! Ha!"

GARY GROTH:

Fallen Comrade

Kim Thompson was more than a business partner. He was an aesthetic compatriot. Art always meant more to us than business, and Fantagraphics Books was always a means to an end: a way of getting art we admired into the world. This imperative forged a bond between us that lasted 37 years.

I met Kim when he accompanied a mutual fan acquaintance on a visit to my three-bedroom apartment sometime in the Fall of 1977. One of the bedrooms served as the office of The Comics Journal, which Mike Catron and I had been editing and publishing for over a year, every month a struggle and near financial disaster. Kim had just arrived in the Washington, D.C. area — he had last lived, briefly, in the U.S. in 1964 — after spending most of his life growing up and indulging his comics addiction in Denmark, France, Germany, Thailand, and the West Indies. He grew up reading European comics (and acquiring an intimate knowledge of their history) and, later, Marvel Comics (the first such that he read being Fantastic Four #108 — missing the end of the heyday by eight issues!). He offered to help us put out the Journal, which we accepted happily.

I remember an immediate kinship. There was not just the comics connection but a mutual love of movies as well. Before he started coming over every day and eventually camping out on the floor, I recall talking to him for hours on the phone — mostly about movies. We may even have talked more about movies in those 37 years than about comics. (It’s funny what one remembers — and how much one doesn’t remember: I spent a night talking to Kim about Hitchcock and the only part of it I remember is that I conflated Bernard Herrmann and George Herriman into Bernard Herriman; I realized my mistake the next day and we had a good laugh over it.)

Kim was a super comics fan. He had a network of fan correspondents when he was in Europe (which included Dean Mullaney, Mark Gruenwald, and others who would go on to make their individual marks in the comics profession) and he was a prolific letter writer to Marvel Comics titles (many of his letters appear in Marvel’s comics in the early ’70s). Working on a magazine about contemporary comics must’ve been a dream come true. He was easily as obsessed as Mike and I were, and he jumped in with both feet; he had a superior European education, so once he learned the editorial procedures and protocols (such as they were), he had the skills to handle such chores as copy editing and news gathering, which he proceeded to do.

In 1978, Mike accepted a job offer from DC Comics and moved to New York; Kim and I carried on. 1976 to '78 was a dismal time for comics: the mainstream had hit rock bottom, the undergrounds were a shadow of their former selves, and the next wave of alternative comics hadn’t yet materialized. This turned out to be perfect timing because it gave us a mission: to change the world (of comics), which we proceeded to try to do for a decade or more until the (comics) world changed to our satisfaction. We fed off each other’s energy. I wrote reviews, and Kim followed suit, not only writing reviews but conducting contentious interviews, contributing to the Journal’s reputation for vituperation and its pariah status among certain comics professionals (though there were many critics to come who would help us maintain that distinction).

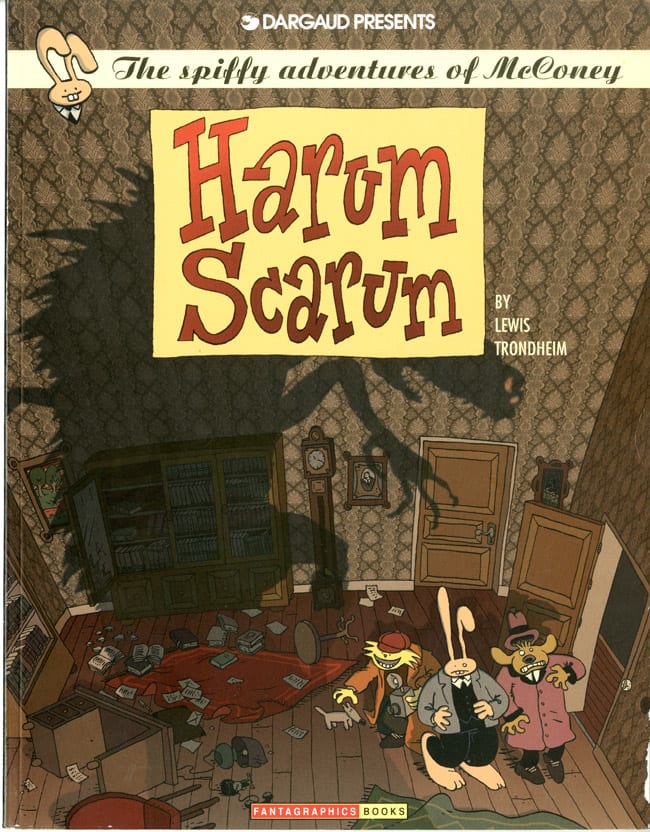

In 1981, we began publishing comics. Why? I don’t know; it’s not as if we had a plan. Maybe we were restless. Before Love & Rockets, which I consider our true flagship book, we published Don Rosa’s Comics & Stories, Milton Knight’s Hugo, and Jack Jackson’s graphic novel Los Tejanos. Kim acquired the Belgian cartoonist Hermann’s Jeremiah, which Kim retitled The Survivors. (“We did Hermann’s Jeremiah because we (mistakenly) thought it would sell. I enjoy Hermann’s work, but my main thought was it’s got adventure, excitement, great drawing,” he later recalled.) We published two volumes in 1981 and 1982, which was a big deal at the time: full-color English-language European albums. We also started publishing Prince Valiant, and befriended the comic-strip historian Rick Marschall, who began editing our Popeye series (all black-and-white, including the Sundays!) and the nonpareil comic-strip magazine Nemo. We were off and running.

In retrospect, it’s obvious that Kim and I were far too strong-willed and individualistic to collaborate on all the company’s projects and that we each needed our own solo projects. Looking back, our intense collaboration on the Journal started fraying in the early ’80s.

If I had to guess, I’d say that Kim started to chafe under my dictatorial, headlong editorial agenda, to which I was so obsessively committed that I was probably oblivious to any dissent or resentment; I probably thought we were 100% in sync when in fact we were only 85% in synch, but that 15% caused tensions. The Journal was my baby and Kim may have felt like he was only going along for the ride — and he wasn’t, quite rightly in my view, content to go along for the ride. If I’m right, this was resolved (without our ever having talked about it) by each of us pursuing projects that reflected our most passionately held aesthetic interests. After all, this only made sense: it would be unreasonable to imagine that any two people would be in total agreement as to what constituted the artistic potential of comics!

We had our combined goal of maintaining Fantagraphics as an ongoing enterprise, but we also needed our autonomy. Our tastes overlapped most of the time, and occasionally diverged, and we indulged these divergences to the betterment of Fantagraphics, because the dynamic added to the company’s catholicity without diluting its essential mission.

In 1982 Kim started editing Amazing Heroes, our bi-weekly (!) magazine devoted predominantly to mainstream comics — now he had his own solo project. He edited it from 1982 until its end in 1992. This was his baby. The amount of work a bi-weekly magazine takes (even with an assistant, which we hired early on, and, later, a managing editor) is enormous, but it played into Kim’s strengths: enormous discipline when it came to scheduling and deadlines, and a continually inventive editorial vision, the result of a mind always in motion.

By 1985 Kim had the process of putting together Amazing Heroes down to a science, and needed something more challenging — I’m making this up as I go — and started Critters, a funny-animal anthology that ran from 1985 to 1990. It featured the work of Steve Gallacci, Mike Kazaleh, and the Danish cartoonist Freddy Milton (who had drawn Donald Duck for European publishers and was interviewed in Amazing Heroes #129 in 1987 — small world), but the title may be best known as the comic book that introduced the wider world to the brilliant and underrated creator of Usagi Yojimbo — Stan Sakai.

Another high point in the ‘80s was his editing and translating the extraordinary collaborators Jose Munoz and Carlos Sampayo. Sinner was a five-issue series starring the eponymous private eye, and Billie Holiday was a stand-alone graphic biography. Kim had wanted to translate their political thriller Nicaragua, but he never got around to it.

In 1995, Kim started Zero Zero, an alternative comics anthology — again, I think it was time for a long-term project that he could invest himself in. And invest he did: it featured an amazing array of multi-generational cartoonists — from Bill Griffith, Joyce Farmer, and Kim Deitch to Joe Sacco, Richard Sala, and Dave Cooper. And what other magazine — or sensibility — would publish Mike Diana and David Mazzucchelli? He kept to a strict bi-monthly schedule and he ended it in 2000.

Kim worked on any number of significant projects in the first decade of this century. We had dabbled in publishing European cartoonists: Jason was an extraordinarily prescient discovery whom we began publishing in 2001. Following were Francesca Ghermandi’s The Wipeout (2003), Martin Kellerman’s Rocky (2005), Matthias Lehmann’s Hwy 115 (2006), and the Ignatz line, produced in conjunction with Italy’s Coconino Press (which included David B’s Babel, Igort’s Baobab, Marti’s Calvario Hills, Lorenzo Mattotti’s Chimera, Sergio Ponchione’s Grotesque, Matt Broersma’s Insomnia, Leila Marzocchi’s Niger, Marco Corona’s Reflections, Gipi’s The Innocents, and Gabriella Giandelli’s Interiorae).

But Kim truly came into his own when he resuscitated his dream to bring bande dessinée to American readers — with a vengeance. Fantagraphics was finally doing well enough financially to accommodate this vision, and he took full advantage of our resources beginning in 2009.

We published our first two Jacques Tardi books that year, and Kim translated a total of nine graphic novels by Tardi (with more waiting in the wings, of course). From 2009 to 2013, Kim shepherded thirty-two foreign translations through the publishing process (including four by Jason). The last book he translated was The Adventures of Jodelle, an immense project on which he worked closely with Guy Peellaert’s son Orson for over a year — a towering achievement for which he was justly proud.

I’ve sketched the highlights of Kim’s “career” (he would understand and appreciate the quotation marks — neither of us thought of this as a “career”), but it barely scratches the surface — it’s impossible to adequately convey his devotion to specific projects and to the goals of the company generally, the all-nighters we pulled to get books to the printer, the tens of thousands of hours hunched over typewriters and computer keyboards and manuscripts, his above-and-beyond-the-call-of-duty proofreading. What I’d like to do, though, is to offer a few words about something I’m uniquely qualified to talk about: the intersection between our personal and professional lives.

As a publisher of cartooning, Fantagraphics Books was an outgrowth of The Comics Journal, so a polemical chip-on-the-shoulder was built into its DNA. As recently as the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, the whole notion that comics was a bona fide art form was still alien not just to the culture at large, but even to the fan sub-culture, most of which inhabited this bland, gray area between a connoisseurial love of great cartooning and the worship of pure dreck (often both at the same time). The only way to break this critical complacency, I thought —and it may not have been the most effective strategy (because it was less a strategy than a compulsion)— was to confront the artistic status quo head-on with the best criticism we could muster — and Kim was right there with me in this Quixotic endeavor, as his reviews of Ronin, Detectives, Inc., The Death of Captain Marvel, and other books attest. Without this zeal, I don’t think we could’ve made a difference.

We brought this combative stance to Fantagraphics Books. When we began publishing original cartoonists in the early ’80s, we considered it a continuation of the same fight we’d begun in the pages of The Comics Journal. We weren’t just publishing Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, and Dan Clowes, and Peter Bagge — we were fighting on their behalf. We believed in what they stood for because they stood for what we stood for. What I’m trying to say is that it wasn’t business-as-usual; there was a revolutionary fervor to the venture, and Kim embraced it.

This was reflected in our office by the argumentative atmosphere Fantagraphics Books inherited — or, rather, never disinherited — from the Journal, and along with that came all the sectarian squabbles that logically result from such unfettered tendencies. A friend of mine who worked in the office for several years and saw me and Kim interact on a daily basis recently told me that he’d never seen any friction between us. My response: Look for a good cataract specialist. Kim and I would have prodigious arguments (and not only with each other, but with employees, or anyone who got in our way or who happened to stumble into the office that day). In a 2002 interview with our mutual friend Ana Merino, Kim described our working relationship:

“At this point, we are just like an old married couple. We have many spats, mostly over silly things, some over serious things. We complement each other well in terms of personality and approach to work. It is sometimes frustrating, for the most part very satisfying, and obviously the results are good.”

I agree with this entirely. It was not an ordinary office environment. Our opinionated and argumentative natures blended seamlessly with our task-driven office-drone personas so that we could each be diligently working on whatever task was before us one moment and spontaneously combust into a polemical squabble the next. Our arguments could be so furious that innocent bystanders (i.e., new employees who hadn’t gotten used to it) would cringe in terror, but to us it was just another day at the office.

Our internal Dilbert exchange that Mr. Reynolds slyly smuggled from our e-mail and placed on the Fantagraphics blog was a mere skirmish compared to what we’d indulge in routinely, practically on a daily basis. My recollection is that we would argue more often about film than about comics. Kim and I would get into such violent arguments over Brian DePalma, for example, that, sometime in the mid ’80s, we agreed to a moratorium on the subject, and never spoke of the director again. (Kim loved DePalma.)

I often told Kim, only half-jokingly, that if his taste in comics mirrored his taste in film, we would never have lasted. Kim loved great films but he also loved films that I found it incomprehensible to like or even enjoy on any level. Not long ago, on his way out of the door, he stuck his head in my office and excitedly told me how great Hostel: Part III was. (I’m still not sure if he was just giving me shit or was too exhilarated not to share this enthusiasm even with someone who he knew wouldn’t reciprocate.) We knew each other too well to bother being polite, and these arguments could stretch over days. Once, circa 1985, the Journal’s news writer Tom Heintjes and I got into a knock-down-drag-out argument with Kim over a news article in the magazine. We prevailed, and Kim’s response was to stay late at the office that night, write a one-act play indicting everyone in the office as out of touch with reality, and leave copies on everyone’s desk the next morning. Like I said, it wasn’t an ordinary office environment.

Many of our disagreements may have sprung from what I perceived was a central difference between us — Kim not only accepted but embraced popular culture on its own terms, whereas I stubbornly refused to. (My position was always that once you do that, you’ve conceded half the battle). Kim’s love of pop culture cannot be overstated. When it came to pop culture, Kim was positively sybaritic; he never slummed and never had a guilty pleasure. In a way, he lived in and through pop culture, as we all do these days — but more deeply than anyone else I knew. Kim could more readily talk about big questions if they were filtered through pop culture. I remember having many, many conversations (and debates) about pop culture with him, but almost none about life. I don’t think Kim was comfortable opening up; even after we’d spent 37 years in the trenches together, Kim could be opaque to me.

Nonetheless, this disjunction, illogically perhaps, never adversely affected our combined vision of what Fantagraphics should publish. We respected each other's publishing choices even if we didn’t always understand them; if one of us didn’t “get it,” he gave the other the benefit of the doubt, but this didn’t in fact happen often. I can’t think of a single instance when one of us objected strenuously enough to the other’s judgment to exercise a veto. More often, we were each overjoyed when one of us would bring in a project that the other wouldn’t have brought in. There was a crazy equilibrium in play, and it may have worked because of rather than in spite of our querulous temperaments.

I’ve been tempted these last couple of weeks to envy the more superficial or “professional” relationship others have had with Kim, and how uncomplicated and easy that generally sounds. But in the end, I’m grateful to have gotten as close as I did to the whole man, with all its emotional messiness.

His diagnosis of lung cancer shocked all of us. (He was never a smoker and was in perfectly good health until then.) I knew the seriousness of it, but had hoped that with chemotherapy and radiation treatments, he could live another year or two, at least get back to the office, complete the work that he’d begun, have more time with his wife Lynn. Shortly after he was diagnosed, I found myself standing outside his home with Lynn, both us trying to make sense of it, but utterly flummoxed. The cancer was more aggressive than we had imagined. Lynn, who is a medical professional, at first helped navigate him through his treatment options and made sure that the best decisions were made. But his condition worsened continuously until those of us closest to him realized — or accepted — that he was nearing the end far faster than we had anticipated. The medical setbacks were relentless. When it became obvious that the chemo could not retard the cancer sufficiently to grant him more time, they made the decision to end it. She became his medical advocate, making sure he had the best care possible.

On June 12th, a week before his death, I was sitting with him in silence. He was, by then, at home in palliative care, comfortable, and substantially free of pain, but his ability to focus had been drifting, and I wasn’t sure if we could have a conversation. I pulled the chair closer to him and told him that I needed to say a few things. I didn’t know exactly what I was going to say, but I knew this was it, and I had to make it count. Maybe it was my demeanor or my uncharacteristically somber —or halting— tone, but I didn’t get more than a few words out of my mouth when his hand reached out to mine and I noticed that his eyes, looking straight at mine, were more fiercely alive than I had ever seen them, and at that moment all our differences melted away, and we were, for the last time, one.

He was alert, articulate, lucid, and for twenty minutes, we spoke about our partnership and our friendship, how different our lives would be if we hadn’t met, how pleased we were that we did, where life had taken us over these last four decades, how much he had accomplished, and how proud he should be of his life’s work.

Whatever tiny toehold Fantagraphics has acquired in the larger culture, whatever Fantagraphics has become, Kim and I built it together.

HELENA G. HARVILICZ:

I liked Kim Thompson, which means a lot since I don’t like anybody. I worked with him briefly at Fantagraphics in the early ’90s. Maybe he was supposed to be my boss. I would catch him observing me but he didn’t do much supervising. It was more like the relationship that Jane Goodall would have with a chimp. He was often amused and occasionally appalled. I had a reputation for being crazy but at least some of that was put on specifically to make him laugh. It was easy to make Kim laugh, actually.

SAM HENDERSON:

I worked with Kim Thompson very briefly. In the comics canon, my own career is a pebble in a pond. I contributed a few stories to Fantagraphics’ flagship anthology Zero Zero in the ’90s and was a regular in Measles, their attempt at doing a kids' comic, before I had a series of my own. He was kind enough to include the first few issues of my solo book in their catalog even though he didn't publish it himself, and point me to the critics I should have it sent to. Even as a consumer of comics and not a cartoonist, sometimes I would order comics and I'd get personal replies. People who worked with him in the office say he was “hands-on,” and even though books were getting major distribution and making bestseller lists, he would still often unload trucks and fill orders himself despite there being plenty of subordinates for such a thing. Imagine Si Newhouse personally taking lunch orders for New Yorker editors.

There was also a Comics Journal message board online, kind of continuing the bile of the magazine, and Kim was again hands-on, posting on threads and humoring people nowhere near as educated, often who hadn't even read the comics they were criticizing, and writing to them like they were equals. There was the usual trolling and sock puppetry one would expect of message boards, though not as much, as Kim moderated as the voice of reason.

A couple weeks ago I did a comics show where almost everyone else involved was at least 15 years younger. I realized they're the first generation to do comics without a chip on their shoulder, without having to defend the fact that they do comics to family and friends, who went to college at the same time there were several schools with programs that dealt with comics academically and not condescendingly. None of that would have been possible without the legacy Kim Thompson helped create at Fantagraphics. Though not the first to do what they did, they did it more frequently and longer, and made more inroads to art and literature circles. The “serious” aesthetic in comics I complain about is still is much more palatable to the masses, and has allowed for giving legitimacy to the subset of comics I identify with. Without his input at Fantagraphics, there'd be no Drawn and Quarterly, Top Shelf, PictureBox, Koyama Press, Alternative Comics, Retrofit, Secret Acres, etc., except as hobbies. I would say Fantagraphics being an early pioneer continuing what the underground was doing is indirectly responsible for my doing work for corporate behemoths yet still able to retain my own copyright.

What are we to do about this loss? I'll tell you what I'm doing. I'm going to continue drawing cartoons. That's what Kim would have wanted.

GILBERT HERNANDEZ:

Kim's passing is one of the saddest losses in my life. I've known him for a lot longer than I've known any of my childhood friends. He was there from the beginning of Love and Rockets and I'm not sure how long the book would have lasted without his and Gary's support in the early days and for all the years since. My comics career would not have flowered without him and I'll always appreciate that. That and he was always easy to hang out with. I'll miss his distinctive cheerful chuckle and grounded intelligence and so much more. We've lost a truly decent man. God bless, Kim.

JAIME HERNANDEZ:

Remembering the kind of publisher Kim was, I really appreciate those times when Gilbert and I were down to the last week of finishing the latest Love and Rockets and Kim would make sure the comic, the production staff, and the printer were all in sync just so we could hit a particular deadline to debut a couple of hundred copies at the San Diego show almost every year.

PAUL HORNSCHEMEIER:

Truthfully, I dreaded getting Kim Thompson’s e-mails. But the origin of that dread is the same as the dentist’s chair, or an advanced calculus exam: things that are good for you –learning, growing– are scary, painful, messy enterprises. And learning about yourself, your limitations, and the complexities of the industry you’d like to think you understood at age twenty-four... well, that puts calculus to shame.

But Kim Thompson taught me about all of those things (minus math and dentistry). I only dreaded his e-mails because he made me get honest about what I wanted to do, how things really worked, and what was really going on in my life. Not many people can do that. But Kim did. And through every e-mail, phone call, or convention conversation, I learned.

Kim was a great teacher and an amazing publisher. Our lives are emptier without him, but fuller for having known him. Thank you, Kim. I’ll try my best to keep learning.

PAUL KARASIK:

Kim Thompson made good books.

I am yet another guy who benefited by his taste in book-making. Without Kim Thompson, the Fletcher Hanks books that I edited would probably not have been published. A couple of other publishers passed, and Gary Groth admits to this day that he himself never really got what the big Fletcher Hanks fuss was all about.

The year of its publication, I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets ended up Fantagraphics biggest seller, right after The Complete Peanuts. Four editions later it won an Eisner Award.

Kim made good books while simultaneously disdaining comics culture, the culture that habitually kowtows to its readers and never criticizes another publisher, no matter how limited that publisher’s editorial skills may be. Instead, as he stood behind the Fantagraphics booth at a comics festival, Kim appeared glad to take your money but silently dismissive of your pathetic choices. A gushing fan rhapsodizing over Jaime's brushline might be bluntly told that it was actually many pen-lines made to look like a brushline. A certain other publisher was dismissed as a moron for publishing good work in an offensive package.

Kim had standards, a vision—and he made good books.

BRUCE McCORKINDALE:

Kim Thompson was a big part of my comics life, both directly and indirectly. During my early '80s college days, I went through many gyrations about whether to pursue creative writing or comics work. Articles and interviews in The Comics Journal (many attributable to Kim Thompson) gave me the revelation that literary aspirations and comic art were not mutually incompatible. This notion doesn't seem like much of a stretch now, but at that time, it was a nuclear explosion in my consciousness. As with many such explosions, the after effects, happily, have never left.

That was Kim's indirect influence. On a direct level, at some point he became my main contact for Fantagraphics work. I never felt worthy, but was always grateful. Kim was thoughtful, generous, professional, and (perhaps most importantly) reliable. There was never a question or concern I ever had that he didn't address with great efficiency and respect. I always thought, "Man, if he's like this with me, I can't imagine how he is with people who actually matter!" When SDCC lost its luster for me and became more of a chore than a fun adventure, Kim was one of the few people I looked forward to seeing. He was smart, affable, and very funny. One time, he described the SDCC patrons who walked around aimlessly, blocking pathways, as "meanderthals." It cracked me up for the rest of that day.

His writings, translations, and editorial work made comics better for everyone. It is a legacy that is hard to match. I am grateful for all that he did for me and (more importantly) the comics community. As a teen, I wanted nothing better than to do comics that Gary Groth and Kim Thompson would like. I don't think I ever quite got there, but even at age 52, the thought has never left me. I will always think a little of Kim when I'm striving to do my best comics work.

JC MENU:

JASON T. MILES:

It's been two weeks since Kim's passing and when I'm not feeling numb from his absence I'm overwhelmed by sorrow and rage by his enduring presence. Gary has compassionately urged me to write about Kim. I dunno, maybe it will help?

I worked closely with Kim for the last six years. Which is to say I lived and breathed Kim Thompson on a near daily basis. I was a member of his family. A truth I wasn't always capable of or willing to recognize and appreciate.

I've worked for Fantagraphics for almost ten years. For the first 3+ years I had almost no contact with Kim. I worked at the legendary Fantagraphics warehouse and it wasn't until I was "called up" to the office by Gary that I became more centrally positioned in the company. I vividly if not accurately remember an early interaction with Kim, where his reply to my question was "because I'm a fucking genius." To which I declared, "I don't think he's kidding." He wasn't kidding, and he was a genius. No doubt about it. There's no other way to account for what he accomplished on a daily basis. Kim was a Hercules. He could do it all and all he did, whether he needed to or not, whether it was helpful or not, he couldn't help himself (he once surprisingly admitted as much to Gary, Eric, and myself). He was like a lion devouring a gazelle. Every fucking day.

Kim was a world-class meddler. When he was stumped on one of his books, or didn't have enough to do, he'd cruise the office and inveigle (a Gary word) his way into other people's books or work duties. He loved to problem solve! He derived immense joy from figuring it out! During pre-production on our EC Comics reprints, he was like a madman, e-mailing Gary, Eric, and myself with ideas and suggestions at all times! Didn't matter if it was Sunday or 1 in the morning on Tuesday. Didn't matter if it was his book or not! All the fucking time he was going strong! Goddamn, I miss his spiraling, bounding energy—even though, on more than one occasion, it compelled me to question my feelings for him as well as question my longevity at Fantagraphics—and that's despite the respect and faith I had in him and continue to have for Gary and Eric and what they've established for all of us to enjoy and argue about and learn from and love. All that petty bullshit and ego-derived resentment... I wish to let it go.

When Eric told me about Kim's initial diagnosis I felt wounded and started to cry and said, "This fucking sucks!" and Eric teared up and we hugged. That's a big deal to me because the relationship I thought I had with Kim is not one I would've characterized as deep. But in that moment I knew we were family and that I'd do anything I could to back him up. I've had deep conversations with Gary and Eric but not with Kim (writing this I can't help but recognize and lament that I could never sidestep the fact that these amazingly weird and wonderful men are my employers). Kim and I never talked about our lives to one another. It was years before Kim asked me a non-work-related question, and it wasn't until after that question that he asked me if I'd seen a particular movie, or read a certain book, or listened to such and such album. Understand that Kim's love language was pop culture (I'm writing that just as much to myself). Kim expressed his love, his yen for life, through his work and through his love of pop culture. When Kim returned from his last trip to Sweden, he brought back a specific book to give to me. Of course he was giving me more than a book.

Kim things I miss:

I miss how Kim would destroy the kitchen/mail-room area. Every day Kim would receive a lot of mail and packages, and everyday he was like a kid feverishly tearing through presents on Christmas morning. Wrapping paper and envelopes strewn about. Several pairs of scissors left open. A mess!

I miss hearing the shake of Ludwig's collar, knowing Kim wasn't far behind. I miss seeing him dote on his dog. Ludwig was perhaps Kim's other love language.

I miss talking about movies and comics with Kim. Several times a week we'd take a moment to talk about Brian DePalma (the one topic Gary and Kim agreed not to talk about) or Paul Verhoeven or our agreement that Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia is the best Peckinpah movie and that Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo is the best Western. I still have his copy of the Pusher trilogy he loaned me. I remember his disdain when I told him I no longer liked Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut. Once Kim knew I was interested in European comics, he grabbed me by the collar and almost every week he'd show me one of his favorite bande dessinée (the first cartoonist Kim ever met was Druillet). We didn't talk about music much with the exception of our mutual appreciation for PIL. Kim loved to host fucked up movie nights. The last of his movie nights I know of – he gleefully showed Irreversible and Antichrist to a now psychologically scarred group of people. I repeatedly refused to go to this sure-to-be-awkward-extravaganza and Kim repeatedly called me a "pussy." There were a few times I attempted to go deeper than pop culture references with Kim to which he would – I later found out – meaningfully reply with dialogue from movies. I always thought the words were his until I once quoted something he'd written to me, stating it really helped me to get over a personal block, and he simply replied, "That's from Pulp Fiction," and walked away.

I miss the delight Kim derived from messing with Gary.

I miss hearing him saying, "He-e-ey, Jason..."

I miss watching him adjust his shirt after asking him a question.

I miss the way he rested his hand on his hip.

One year at San Diego Comic-Con a group of us were having a hard time finding a place to eat. We'd just finished a fifteen-hour day and were hungry and tired. Place after place was full up until we came upon an all-you-can-eat Brazilian BBQ joint. The only hitch being it was $36 per plate and well out of our price range. Kim stepped up and generously offered to pay for all of us as a reward for our collective hard work. I can honestly say it was one of the most memorable and greatest meals of my life. We all got shitfaced on meat! Kim giggled all the while we ate ourselves sick! At one point the owner of the restaurant came up and put his arm around us and said with a satisfied look on his face, "You are all now a part of my family!"

A few months ago Kim invited me over for lunch. He'd been out of the office for a couple of months, due to his illness, the severity of which had not yet been determined. I spent two hours with Kim. It was easily the longest one-on-one, non-work time I'd ever spent with him. He didn't speak much, mainly due to the pain, and he wasn't interested in talking about work or pop culture. All of our go-to speaking points were gone. There were long stretches of silence until I decided to ask him about his life away from work. I asked him about his parents and brother and how he met Lynn. I asked him all the things I could think of that had nothing to do with work or comics. At one point he told me that he felt he'd been forced into thinking about his legacy. I can't emphasis how humble, unassuming, and unpretentious he was at this moment. Frankly, I was shocked because Kim could be proud to a fault about Fantagraphics and its impact on the medium and industry. I nervously asked him about which aspects of his legacy he was thinking about, and I specifically remember him saying, "All of it. Comics as art. I think we did it and that makes all this a little easier to accept..."

A week and a half before his passing, Eric and I went over to visit. He told us he wasn't in any pain and he appeared comfortable. We spent a lovely, sorrowful afternoon chatting about movies and comics, for by now we knew his time here wasn't long. I did not want to leave.

The Friday before he passed away I went over for what turned out to be a very brief visit. Kim was very tired and it was apparent that he was using all his strength to focus on me. He apologized for being so tired. I knew this would be the last time I would see him. I leaned in and put my hand in his. He squeezed my hand and I told him, "I've got your back. Give me a call if you or Lynn need anything." He looked at me while nodding and said, "I know. Thank you."

TONY MILLIONAIRE:

Kim was always so quiet around me that I never really knew what he was thinking about. One day he e-mailed me: "That latest Sock Monkey book was a real mind-fuck." I asked him three times to explain what he meant specifically, but he would not answer. Months later we got into long e-mail discussions about Stanley Kubrick and I got a glimpse into his brain. But when we went to Norway for the Oslo Comics Expo, that's when he really shined. He was open, talkative, like he had come back home and we were his guests, like he was welcoming us to a place he knew. There's something different about the way Scandinavian types think and act, and he seemed very comfortable and happy there. That's when I finally got it about his Northern European mind.

I'm grateful to him for everything he did, the Comics Viking.

PAT MORIARITY:

I got to know Kim Thompson pretty well in the 1990s. He and Gary offered to publish my first attempt at a sequential narrative, a story called "Popcorn Pimps" that appeared in Graphic Story Monthly, an anthology. Not long after that I showed up on their doorstep and found myself working with the guy. Kim and Gary were my bosses but Kim was the one who seemed to know the specifics. Kim was more of an overseer than a participant. He was the king of the memo. I'd get a memo, typed cleanly on brightly colored yellow paper, like every day. Sometimes several, depending on the workload. It wasn't just me; these memos were handed out to just about everyone, with their orders of the day. Kim had an amazing mind, able to spot the most subtle grammatical errors instantly. I found this most helpful and annoying. He had a vast knowledge of all things cartoon related as well. I spent almost eight years of my life working in that small house with Kim and company, on a thousand projects, to promote the “greatest cartoonists in the world.”

Kim's opinions hit hard with me, whether I agreed or not. His take on cartoonists and their work was extremely honest, usually delivered in hilariously brutal words. Before Sacco's sales figures got off the ground, he'd refer to the back stock as “Mount Palestine.” He was perplexed by my close friendship with Shary Flenniken because she was “crazy” but then he'd chuckle and admit that he thought all cartoonists were, especially the best ones. He once told me that I was too well adjusted to be a truly great cartoonist. Compliment or insult? That's Kim, and that's why I loved him. And feared him. I'm just another soul whose life was forever changed for the better, because of his sweet soul, which he kept mostly disguised in sardonic humor. Kim was kind of a punk rocker in attitude, although he was no punker. Thinking about Kim, the refrain I hear in my head, what I seem to remember hearing Kim saying the most at work was “Fuck 'em!” followed by his trademark nervous chuckle. Fantagraphics will just not be the same without Kim Thompson, and neither will I.

ERIC REYNOLDS:

Kim Thompson was my friend, a partner in the trenches, a mentor, a role model, and a near-daily presence in my life for the past twenty years. His absence leaves a big hole. I’ve spent half of my life admiring him, fighting side by side with him, and learning from him and I still can’t believe he’s gone. I loved him a lot, and I know he loved me.

Kim was not your traditional fount of fatherly wisdom, and he wasn’t my go-to guy for all of life’s problems, but whenever I needed him, he was there as much as anyone ever has been for me. He was an exceedingly loyal friend, a good man, and a singular human being.

He was hardly flawless. He could be mercilessly honest to the point of cruelty. His mediocre was usually better than your best, and he had no trouble letting you know when you weren’t up to snuff. He did not suffer fools, but he was happy to make fools suffer. His bedside manner ruffled the feathers of many talented cartoonists who craved more in the way of ego-stroking that honest evaluation. There’s a reason that my business card, for many years, described by position in part as “Paid Apologist.”

He was not always the easiest guy to know in the traditional sense of what you think of as being a close friendship. Maybe it was those inscrutable, Scandinavian genes. A predilection for written correspondence over face-to-face conversation (even when sitting ten feet away). Kim’s polymath brain was just wired differently than the rest of us. Nine languages! This was truly a brain for the ages. I wish it could be preserved for future generations to study. But underneath that cool, stoic, Danish exterior lay a French bohemian and an American Punk who both also fought for dominance.

My employment in the Groth/Thompson empire came via The Comics Journal and Gary Groth in 1993. Kim was elusive to me for some time. In 1994, I think, I gave Kim one of my minicomics and asked him if he would give me his honest opinion. I haven’t been able to find his typewritten reply this week, but I’ve saved it all these years. It was brutal, and I still can quote from memory the line, “Your inking obfuscates a multitude of sins in your penciling.”

A more diplomatic but less effective editor might have phrased that as, “You’re a pretty good inker.” But I respected him for it, he was dead-on in his assessment, and in hindsight I suspect it might have been a turning point in our relationship, simply because I wasn’t offended by it. When I switched “teams” in 1996 from the Journal to Fantagraphics (it’s hard to understand now, but there really was more of a separation of church and state at that time), that’s when we really developed a connection. Our status as two ex-Journal editors gave us a certain camaraderie in the office that was unusual; few other outgoing-Journal editors have had the desire and option to stay with Fantagraphics, but I lucked out.

For the past fifteen or more years, Kim absolutely treated me like his equal. But let’s be real: I was not his equal. Yet treat me like one he did, and we became close, in our own way, and spent a lot of time with each other over the years. Not just in the office, but traveling to cons and sharing hotel rooms more than a few times. He was a quirky travelmate, to say the least, and still the only man I’ve ever traveled with who brought a full-length bathrobe and slippers with him everywhere he went. (His dedication to comfort over fashion pretty much 24/7, outside of weddings/funerals, was truly a testament to his unpretentiousness.)

My favorite trip with Kim was flying round-trip from Seattle to SPX in 2000. Then, from SPX, we drove (actually, Kim did all of it) to Manhattan and back to attend Joe Sacco’s book release party for Safe Area Gorazde at the Knitting Factory. I remember asking him, as we drove through whatever tunnel it was that took us into Manhattan, if he got nervous driving in New York City (I would). He looked like he literally couldn’t comprehend the question. “Why would I?” The unflappable Kim Thompson. Sacco’s book was going to be a real milestone for Fanta, and we both knew it, and it was fun to share that time with him.

On the flight back to Seattle, I pulled out a copy of Michael Kupperman’s Snake ’n’ Bacon’s Cartoon Cabaret that I had picked up at SPX. I started howling with laughter. Kim wanted to know what was so funny, so I shared it with him, and we sat there, these two grown men, laughing out loud and repeating choice punchlines. “Ssssssss!” “I’m good on a sandwich!”

And then there was the Comic Book Cruise, also in 2000 (a trip which still feels like some kind of bizarre fantasy I must have hallucinated, but that’s another story). I took a picture of him on that trip that I’ve always liked, of him on the beach of Cabo San Lucas, holding three iguanas with a palpable sense of pride that I remember kind of baffled me but I found endearing at the same time.

Being two of the earlier risers in the office, Kim and I would routinely have the upstairs of the Fanta HQ all to ourselves for an hour or more during many mornings over the past several years. I’m going to miss those early morning bitch sessions. Over the past four months, since Kim has been too sick to work, I’ve routinely had these moments — always in the morning — where I forget he’s not going to be there and expect to hear Ludvig, his beloved dachshund, bark at me as I enter the kitchen. But he doesn’t.

Kim is one of the most whipsmart people I’ll ever know, and it makes me sick that I -– and all of us -- won’t have access to that deep reservoir of knowledge anymore. But not just the knowledge! The critical acumen that I never stopped learning from, and probably never will.

At Fantagraphics, we argue a lot. A LOT. Kim is one of the two best arguers I’ve ever met in my life. The other is Gary Groth. As I once put it while caught in the middle of one of their most epic – and hilarious – debates: irresistible force, meet immovable object. It was something to behold, and occasionally fear. But you know what was even more impressive? Watching the irresistible force and immovable object team up like superheroes to crush some poor opportunistic schmuck that dared offend or underestimate them.

I’m pretty sure that they’ve argued themselves out of going out of business at least a few times. Their collective, sheer force of will (or perhaps stubbornness) has floated Fantagraphics when economics or business sense have not, when many other would-be empire builders would have long imploded under the weight of their own egos or demons or any of the myriad other ways that businesses fail. But Kim and Gary simply wouldn’t let Fantagraphics fail. That may sound corny, but really, I’ve witnessed it.

Here’s the thing: nobody was a bigger Fantagraphics fan than Kim Thompson. There was no false modesty on that front. Without fail, as we put together a new catalog every season, Kim would say at some point something like, “We really are the best comics publisher ever.” But it wasn’t an ego trip, it was a passion, a passion to publish the best work that he could, not for his own glory but for fellow fans to enjoy. For a self-professed “stone-cold atheist,” he came as close to living out a “higher calling” as anyone I can think of.

Personally, Kim’s dedication has afforded me a career in the medium I adore, with the publisher I admire the most, working with most of my favorite cartoonists of all-time. To bring things full circle, it occurred to me this week that my own very first published work –- fan illustrations of characters like Plastic Man and Kraven the Hunter -- appeared when I was a teenager in the 1980s (several years before I started working at The Comics Journal), in the pages of Amazing Heroes, which was edited by Kim Thompson. As a kid, Amazing Heroes was kind of my Internet. I owed Kim before I’d even met him!

Fantagraphics will survive, sure. I have no doubt about that. But it won’t be quite the same. I drove Kim to the hospital one day, earlier in the year, for a doctor’s appointment some weeks after the cancer had kept him from working for the first time in his adult life. He asked me for a State of the Union. I filled him in, and he said, “I guess you guys really don’t need me.” I told him to stop fishing for compliments. He laughed. But he was wrong. We’ll always need him.

On Wednesday night, as I saw his name trend on Twitter (along with Tony Soprano, an association he most certainly would have been tickled by), and I saw my e-mail inbox and Facebook wall flood with tributes to Kim, I was overwhelmed with emotion by seeing how many people’s lives have been improved by the books Kim midwifed into the world, because really, that’s all he ever ultimately wanted to accomplish.

Kim showed me continued, unwavering loyalty throughout our friendship. I love him for it and will continue to endeavor to be worthy of it.

JOE SACCO: