Venerable comic book artist Carmine Infantino passed away April 4, 2013. The cause of death was undisclosed. He was 87 years old.

Infantino was best known for his beautifully designed artwork characterized by a spare, abstract, modern-looking approach perfectly in tune with the late 1950s and 1960s, when he reached his creative maturity. Infantino was editorial director at DC Comics beginning in 1967 and served as the firm’s publisher from 1971 to 1976.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, May 24, 1925, Infantino found work in comics as a teenager while attending the School of Industrial Art (later the High School of Art and Design) in Manhattan. He and his boyhood friend Frank Giacoia worked as a team: Giacoia penciling and Infantino inking. Their first published work was the Jack Frost story in Timely Comics’ USA Comics #3, which hit newsstands just before the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

Before long, the two friends switched roles, with Infantino penciling and Giacoia inking. Together and separately, they drew comics for Hillman, Prize, the Jack Binder shop (which supplied Fawcett with editorial content), and other companies. In 1947, Infantino got his first assignment at DC (then National Comics) drawing the debut story of the Black Canary in Flash Comics #86 (August 1947). Then he began work on the Flash and other features and became a favorite of editor Julius Schwartz. Like a lot of young artists at the time, Infantino admired Milton Caniff’s comic strips Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon: Infantino's male protagonists took on the Caniff look.

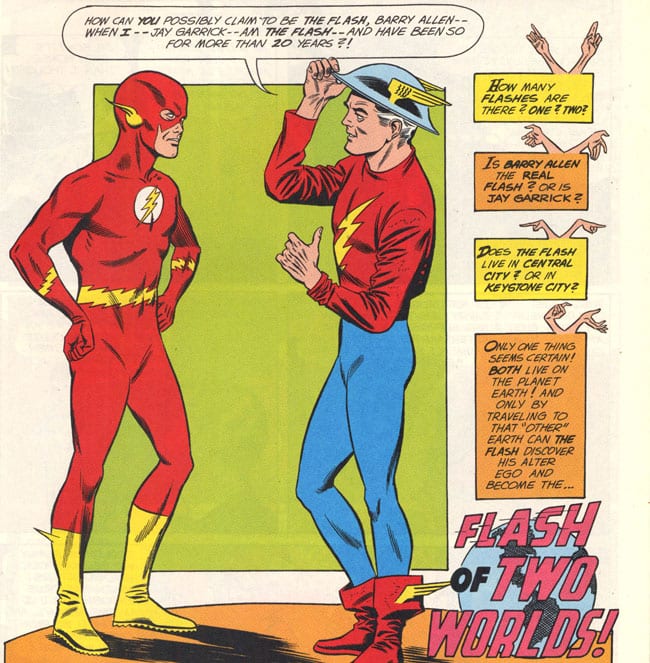

In 1956, Schwartz chose Infantino to pencil a tryout issue of a new version of the Flash. Working from a script by Robert Kanigher, Infantino’s pencils on “Mystery of the Human Thunderbolt!” in Showcase #4 (September-October 1956) achieved a new kind of superhero action, emphasizing design and movement, with a kinetic quality that was exhilarating. Infantino’s design for the retooled Flash — an all-red costume except for bits of yellow — was like a sleek, modern sports car. His visual conception, along with uncommonly mature stories by Robert Kanigher and John Broome, sold the reinvented character to the burgeoning number of baby boomers who were looking for something new and exciting. The success of the Flash led to the reinvention of Green Lantern and other Golden Age heroes at National/DC, which in turn inspired Stan Lee and Jack Kirby to create the Fantastic Four in 1961. Later comics historians would identify Showcase #4 as the kick-off for what came to be called the Silver Age of comics.

In the late 1950s, Infantino went to art school and his work changed. “There came a point where I felt I had to get back to school,” Infantino recalled in his book The Amazing World of Carmine Infantino. “I just felt there was something missing.” Infantino took classes at the Art Students’ League, and then at the School of Visual Arts with teacher Jack Potter. “What Jack taught me about design was monumental, and I went through a metamorphosis working with him. My work started to grow by leaps and bounds. I was achieving individuality in my work that wasn’t there before. I threw all the basics of cartooning out the window and focused on pure design.” Infantino’s work took on a dynamic quality that moved the eye across the page to focus on the point of each panel, rather than being distracted by background details. He continued to refine his style over the next few years on features such as Adam Strange. After this metamorphosis in his mid-30s, Infantino became one of the great comic book artists, as opposed to just a very good penciler.

In 1964, when Schwartz was given the ailing Batman titles to edit, he tapped Infantino to update the look of the Dynamic Duo. With Detective Comics #327 (May 1964), Batman and Robin had a “new look” designed by Infantino (with inker Joe Giella), the beginning of a new era for the characters. Two years later, when DC felt it was losing ground to Marvel Comics, Infantino convinced the powers-that-be to make him art director. He designed virtually all of DCs covers in an intensive campaign to make them more dynamic and eye-catching.

DC’s editorial director Irwin Donenfeld was ousted after the company was purchased by Kinney National Services (later Time Warner) in 1967, and Infantino was informed “you’re editorial director now.” One of his first moves was to promote artists to editorial positions. “The books were sterile-looking in those days,” Infantino recalled in his autobiography. “Julie Schwartz, Mort Weisinger, and Murray Boltinoff were purely literary men. My feeling was that we needed visual people also.” Joe Kubert, Joe Orlando, Mike Sekowsky and Dick Giordano became editors. Infantino also canceled old titles, revamped others and started a host of new ones. One of his coups was hiring Jack Kirby away from Marvel Comics in 1970. That year, DC’s lineup was very different than the slate of titles Infantino had inherited.

Infantino became DC’s publisher in 1971. In that capacity, he initiated the first company crossover, Superman vs. the Amazing Spider-Man, and consulted with writer Mario Puzo on the story for the movies Superman and Superman II. During this time, creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were engaged in a lawsuit to regain ownership of Superman, and Infantino worked — some said aggressively — to defeat their efforts. In 1976, Warner Communications ousted him. Infantino’s tenure had been stormy and many in the creative community felt he had been an effective editorial director, but wasn't up to the job of publisher.

After leaving DC, Infantino sought other management positions in comics and related fields, but was never able to find one. Finally, he returned to freelance art, first in Warren’s black-and-white magazines, and then at Marvel Comics. He penciled that publisher's highly successful Star Wars comic book for several years, and worked on a number of other series for the publisher such as Spider-Woman, Nova, Ms. Marvel and Iron Man. In the 1980s, he returned to DC Comics and stayed with it until Crisis on Infinite Earths in 1985 spelled the demise of the Flash.

A retired Infantino became a frequent convention guest in the 1990s, signing copies of his autobiography The Amazing World of Carmine Infantino (2001), which he collaborated on with J. David Spurlock. During this time, according to Michael Dean in The Comics Journal #262 (November/December 2004), he engaged in a lawsuit “against DC comics, claiming it had stolen the rights to to several characters created by him, including The Flash.” Infantino withdrew the lawsuit shortly thereafter. In 2010, he was the subject of Carmine Infantino: Penciler, Publisher, Provocateur, a book by Jim Amash and Eric Nolen-Weathington. He was inducted into the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1998 and into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame in 2000.