IN THE ROTUNDA of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, each state is permitted to place statues of two of its native sons whose lives or works were somehow worthy of enshrining. As the number of states grew, so did the number of statues until they were too numerous for the Rotunda. Today, those statues stand in the Hall of Statues just off the Rotunda.

These bronzed personages on pedestals include presidents and statesmen and generals—Washington, Lincoln, Jefferson, Robert E. Lee, and so on. Exactly the kind of roll call you'd expect. Until you get to Montana.

Montana's two statues are of Jeannette Rankin and Charles M. Russell. Never heard of ’em, you say? How can they be heroes if they're unknown? Depends on your idea of heroism, I guess.

Jeannette Rankin (1880-1973) was a leader in the women's suffrage movement and in 1917 became the first female member of the U.S. House of Representatives. She served until 1919 and was one of only 50 members of the House to vote against declaring war on Germany. She was back in the House in 1941, and when war was declared on Japan following the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, she voted against the declaration—and this time, she was the only dissenting vote. Why? She was a pacifist, first of all; but she also felt that "a good democracy" should not be on record as voting unanimously for war.

Charlie Russell (1864-1926) is renowned as the self-taught "cowboy artist" whose depictions of the old West in watercolor, oil, pen-and-ink, and in clay and bronze sculptures are highly regarded for their authenticity. And for their sense of humor. Before he became famous as an artist, Charlie hunted and trapped, herded cows, and broke broncs. One winter, he lived with the Blood Indians in Canada. They gave him the name "Ah-wah-cous," or antelope (possibly because the pattern of his riding breeches in the back reminded them of the south end of an antelope running north). Charlie always spoke of Indians as the only "real Americans," and he was an early conservationist and environmentalist (before there was such a term).

Russell's is the only statue of an artist in the Capitol. Fittingly, the only artist monumentalized in the Capitol is a cowboy artist: the West, after all, is the most distinctive aspect of American cultural history, and the history of the country's expansion into the West —and the legends and lore associated with that expansion—are the nation's mythology.

A pacifist equal rights advocate and an artist. With heroes like these, Montana is my kind of place. I like the scenery, but it's the people that nominated Russell and Rankin; and one of those people is Stan Lynde.

"Charlie Russell has achieved the category of sainthood in Montana," Lynde told me when we talked in September 1992. "No politician can succeed in Montana unless he's for Charlie Russell and against gun control," he said, with a grin.

"Russell was a major influence on my life and on my career choices," he continued. "Like many families growing up in the thirties, my parents were quite poor during that period. The Depression was in full swing in Montana, and we survived primarily by our garden and my father's rifle. And the only decorations in our house were Russell pictures taken from a calendar and put on the wall, so I grew up looking at Charlie Russell paintings."

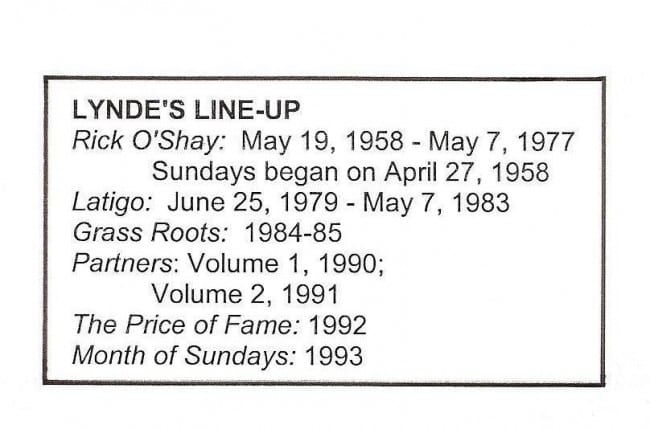

Montana is clearly Lynde's kind of place: he depicts it lovingly in his work—in the comic strips Rick O'Shay and Latigo, in the graphic novels Pardners and The Price of Fame, in the cartoon series Grass Roots, and in the prose novel The Bodacious Kid, and seven others about the out West adventures of Merlin Fanshaw. All of these are products of Cottonwood Publishing, Inc. (formerly Cottonwood Graphics), the company Lynde formed in 1989 with his wife Lynda (“the Lady Publisher”) for the purpose of publishing and marketing his work.

"Lynda had been a business woman in many areas," Lynde explained. "She'd run a bed and breakfast; she'd been a realtor. She'd been a real estate developer. And we wanted to do something that we could do together."

Although Lynde had left Rick O'Shay in 1977 and its successor, Latigo, had ceased in 1983, he had never stopped cartooning. "I did a self-syndicated feature called Grass Roots for weekly papers. And then I did a collection of those in book form, and we were thinking of some way to go back into cartooning. I was fascinated by the graphic novel idea. We talked about going with a major publisher, but, everything considered, we decided to try to do it on our own, so we formed Cottonwood Publishing as our own company."

The first publication from Cottonwood was Lynde's memoir, Rick O'Shay, Hipshot, and Me, published in September 1990. It was a fitting choice: Lynde's first career as a syndicated cartoonist had begun with Rick and Hipshot. The book reprints ten stories from the strip and as well as Lynde's autobiography.

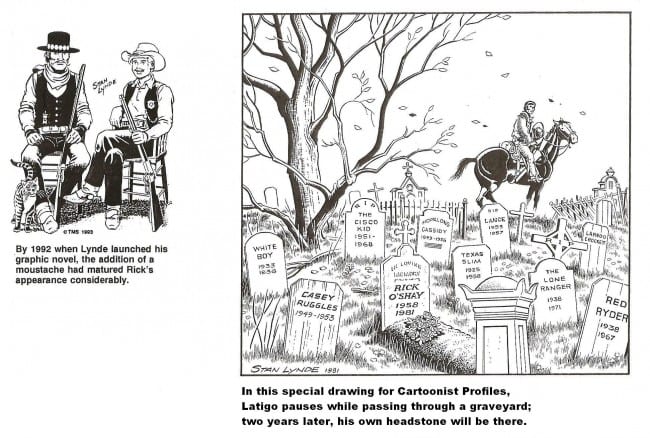

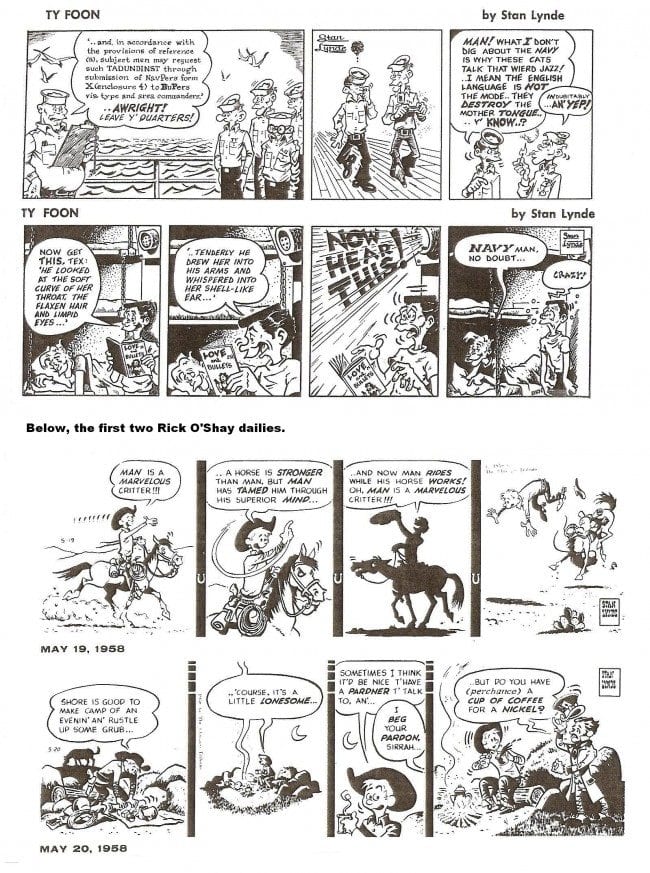

BORN IN BILLINGS, MONTANA in 1931, Lynde grew up on a ranch near Lodge Grass on the Crow Indian reservation where his father raised sheep. After graduating from high school, Lynde went to the University of Montana in Missoula for a year and then found himself in the Navy during the Korean War. Although he repeatedly requested sea duty, he served instead in the personnel office on Guam. There he created his first regularly published comic strip. Running daily in the base newspaper, Ty Foon featured the misadventures of the title character, a hilariously lucky sailor, and an assorted supporting cast.

"I couldn't have been happier," Lynde wrote. "At last, I was producing my own strip, seeing it in print every day, practicing my timing and developing my drawing for a real—if captive—audience."

He was having such a good time that when his eighteen-month tour was up, he requested (and received) a six-month extension. When discharged in 1955, he landed a job as reporter and artist on a weekly newspaper in Colorado Springs, Colorado, but left after a short time to try his luck in New York.

Unsuccessful at selling a strip about Navy life (to parallel Beetle Bailey, which, by this time, was well on its way), Lynde found work as a typist at the Wall Street Journal. In his spare time, he sold cartoons to various Navy periodicals and miscellaneous drawings to other publications. And he enrolled in the School of Visual Arts, studying with Jerry Robinson and Burne Hogarth. And then in early 1957, the idea for a Western comic strip began to take shape.

On television, the Western commanded prime time. For at least an hour (sometimes two) every evening, cowboys and Indians and gunfighters and rustlers galloped across the tiny screen. This was the year of Maverick, Restless Gun, Cheyenne, Tombstone Territory, Wagon Train, Zorro, Colt .45, Gunsmoke, Have Gun Will Travel, and even Sgt. Preston of the Yukon.

"Sometimes cartoonists do what we do because it's going to be saleable or it's what a syndicate or an editor is going to be interested in even if we have to sublimate our own point of view," Lynde told me. "I was caught early, as I've indicated, by the romance and the glamour of the West—and not only from Russell's works but from first-hand experience and knowledge of some of the real old time cowboys—so my interest, I suppose, was in glamorizing the West because it seemed very glamorous to me. At one point, I wanted to do a feature something like Hal Foster's Prince Valiant or Warren Tufts' Casey Ruggles or his later Lance. Historical. Pretty much a serious adventure.

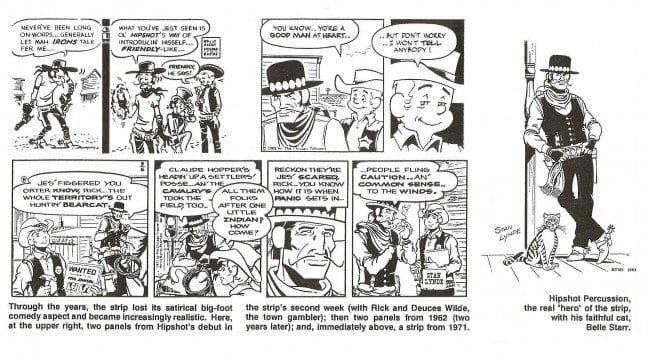

"But by 1957, instead of wanting to do a serious adventure strip, I had decided to produce a feature which would satirize the fictional Western, the TV Western, from the standpoint of the authentic West in which I'd grown up, taking the Western conventions and stereotypes of fiction and standing them on their heads. So Rick O'Shay began as a spoof on the synthetic West, or what Gary Cooper used to call `easterns in big hats.'

"Fiction's honest, brave, fighting marshal became the amiable naive Rick O'Shay," Lynde continued; "the steely-eyed, remorseless gunfighter became the hard-boiled but soft-centered Hipshot Percussion; the Indian, noble redman and victim of the white oppressor, became the sly, avaricious capitalist Chief Horse's Neck, who emerged triumphant and wealthier after every encounter with his would-be exploiters."

"Oddly enough," I said, "despite all the Westerns on television, there weren't that many comic strips that were Westerns. In fact, I can think of only a couple. Dan Spiegle's Hopalong Cassidy had stopped in about 1955."

"Yes, and I admired his work very much," Lynde said. "He was very good with Craftint doubletone in those days. Having tried it myself and found what a difficult medium it is, I think probably Dan was the best since Roy Crane at that."

"Fred Harman's Red Ryder was still going then," I said. (See Harv’s Hindsight for August 2004 for the Red Ryder story.)

"Yes," Lynde said. "The ones that appealed to me the most— the Westerns that I saw and was exposed to as a kid—were Red Ryder and J.R. Williams' Out Our Way. I admired them for the same reasons. Both Harman and Williams had been here and were coming from a place of authenticity, so I admired them especially."

"I thought Harman had such a feel for things like fence posts and board walks," I said. "Everything looked like it was made out of wood, and his horses were so great, too."

"They were," Lynde said. "The style was rough—in some cases, almost a dry brush style—but I thought it especially befitting the Western. But Red Ryder was on its way out in 1957. In fact, the Western wasn't all that hot with syndicate editors then in spite of all those television shows. I ran into that opposition, very definite prejudice against Westerns on the part of a number of syndicate editors to whom I submitted my stuff before Tribune Media Services [then the Chicago Tribune-New York Daily News Syndicate] accepted it."

It was Maurice "Moe" Reilly who made the decision for TMS, hoping Rick O'Shay would replace Ferd Johnson's Texas Slim in many newspapers' line-ups. Johnson was dropping Texas Slim in order to take over Moon Mullins for Frank Willard, who died early in 1958. Lynde’s strip started May 19, 1958. Reilly nurtured both Rick O'Shay and its creator, as Lynde recounts in his memoir.

THE SEQUENCES OF THE STRIP reprinted in the book show how dramatically Rick O'Shay changed over its twenty-year run. Beginning as a mock Western, it evolved into a much more realistic saga, and I asked Lynde how that happened.

"I think probably it goes back to what I'd originally planned," he said. "I'd originally wanted to do an illustrative fairly authentic not a big-foot type art style, and eventually it sort of eased that way. I did a lot of learning. And some of the characters matured and developed faster than others. Hipshot chief among them. And I found I had to bring the rest of the characters up to his standards. Rick had sort of lagged behind.

"And the readers themselves urged me on. At first the strip was something of an anachronism. It dealt with the twentieth century intruding upon this sleepy little Montana town. But the readers tended to want their West to be the Old West. And I kept hearing that, and finally, I thought to myself, That's what I want too. So in the late sixties I adopted a centennial theme: if it was 1969, it was 1869 in the strip. And I kept that going.

"Once we were in the Old West," he continued, "I felt I had to be authentic about it. Again back to Russell: Russell sort of set the standard. Painters of the West today are locked into doing it very authentically; you don't find much successful impressionism of Western subjects.

"It's almost as if the viewer wants authenticity in the detail," he said. "This goes even deeper. I had a friend from Ireland, who said he believed the West was our folk legend, similar to their knights of the round table or Robin Hood. And it certainly is the thing that is recognizable in Europe and elsewhere about the U.S. There's something about the space and the freedom that we had as a people that I think finds its expression in the Western, that frontier spirit and feeling."

I agreed: "I have said on many occasions that the Western—whether it's about a cowboy or a gunfighter or Marshal Earp—whatever it is, it's the American mythology, and those characters are the archetypal Americans. And in fact, I've even tried to make a case for superhero comic books simply being another manifestation of the same thing. And if you think about it, they really are: the classic Western story has to do with an individual who's posing his sense of right and wrong against what's around him, and he really is a vigilante--just like the superheroes always are."

"That's exactly right," Lynde said. "It has been pointed out that Star Wars, for instance, was definitely a Western, a very very good adaptation."

He continued: "I think one of the great evidences of the vitality of the Western is what people have done to it. How it has been corrupted and abused, how it survives the debunkers who periodically rise up and revise history. They've done it with the gunfighter myth and with the Indian myth. This year it's popular to do it with Christopher Columbus and the early explorers. But it survives all that. It survives bad Western movies by Hollywood.

"One of my frustrations has always been that the prevailing wisdom on the part of newspaper editors or TV or movie people—or whoever, or syndicates—is that Westerns don't work. Then we get a good one like Lonesome Dove, and everyone says, Well, yeah—Hey, that works. And then they do some more Westerns and they do a bad one or two, and they don't work, and they go back and say, Westerns don't work. That stuff doesn't work. Well, Westerns do work if you do them right and authentically."

Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven was one of those successful Westerns. And it was influenced by Rick O'Shay. Michael Price, movie critic of the Fort Worth Star Telegram, made the observation in his review of the film: "The very mentors to whose memories Eastwood has dedicated Unforgiven, Don Siegel [The Shootist among others] and Sergio Leone [Fistful of Dollars, etc.], had long ago acknowledge the funny papers' Rick O'Shay as an influence."

Lynde noted one striking similarity: "There was one scene in The Unforgiven where the Eastwood character was shooting at a tin can and missing and finally goes back for his shotgun, which came from a Sunday page I'd done in Rick. In fact, I'd done it a couple times, with different punchlines. A friend suggested that I send one to Eastwood with a note saying, Saw Unforgiven--and I forgive you," he finished with a laugh.

Lynde has done a great deal of research in producing his strips, including reading historical accounts and logbooks and personal diaries written during the period of his stories.

Said he: "I've had cartoonists ask me why I go to all the work of making sure that all the detail is totally authentic and accurate. And my answer has always been that I feel there's something about doing it as authentically as I can that will communicate to people, even those who don't know. For example, when I read the sea stories of Melville or Dana, I don't know anything about the sea, but I'm always given the impression that, This is right. And I think that comes through."

I observed that his passion for authenticity goes beyond the visuals: "Even the language, the way the characters talk, sounds authentic," I said. "I have no way of knowing whether it is authentic. But it certainly doesn't sound like Hollywood cowboys: it sounds like real cowboys."

"Well, I appreciate that," Lynde said. "I hope that's true. Cowboys were colorful talkers. They certainly were. They may not have been altogether literate, as far as reading was concerned, but they had mastered their language. You'll find a lot of exactly what we're talking about in a book called Trails Plowed Under. It's a book of stories by Charlie Russell, told in dialect or by a ‘character.' They're wonderful. Russell's stories are perhaps almost as good as his art."

I said, "I ran across an expression in one of your novels—someone who didn't have `enough clothes to pad a crutch.'"

"Yes," Lynde laughed. "That's from Charlie Russell. Really descriptive. It's the kind of thing the old timers did a lot of."

We talked about his characters. I asked: "To what extent do you feel that the characters are whispering in your ear about what they're going to do next?"

"That's a pretty strong feeling," he said. "I often think of them as actors, and they have to negotiate for billing and what have you. Once a fan who had stayed with me for a long time wrote to me upset and said Hipshot wouldn't have done that—whatever particular thing it was. He knew Hipshot and he knew Hipshot wouldn't have done that. And I thought, All right, it's that real to them."

"But the characters are real to you, too," I said.

"Yes, they are. They become your children after a time, and that's also what made it a bit painful when I lost custody of them after awhile."

"Lost custody, that's a good expression," I said. "But Hipshot, he's one of those characters like Snuffy Smith, who comes along and edges the principals off the stage."

"Yes, that character is so strong that I think anything else that I do would be just an approximation of trying to come close to this one," Lynde said. "It's remarkable. During the run of the strip, Hipshot would actually get romantic mail from women, all ages, from little girls aged ten to ladies in the eighties. The men liked him, too, and that doesn't always happen.

"And I knew he'd taken over," Lynde continued. "I knew early that that's what was happening. Rick was still needed as the balance wheel, and the friendship had some historic roots, much like the Doc Holiday-Wyatt Earp friendship, the outlaw and the titular good guy. And I felt that there was a mutual attraction. Rick is Hipshot's only friend, probably. He is the only one that's been allowed to see beneath the tough exterior. And there's a little envy there. I've always felt that Hipshot would like to be as well-liked as Rick, or perhaps have a family and so on; and Rick perhaps would like to be as tough as Hipshot," he said, chuckling.

One of the most moving of Lynde's stories about the relationship between Rick and Hipshot is called "Trackdown." Reprinted in the memoir, it recounts Rick's adventures in tracking down men who had bushwhacked Hipshot. Rick resigns as marshal and goes off on his own. But one of his prey is killed in a gunfight before Rick gets to him; and the other one is killed by a bolt of lightning just as he gets the drop on Rick. When Rick returns to report the results of his search to Hipshot, the scene is played with great restraint.

As Lynde said: "Their reunion is very understated, and that's the Western tradition: Rick just says he met a couple ‘old friends' of Hipshot's, and they passed away. That was one of those cases where I had a chance to show the depth of the friendship. Rick was willing to lay his life down for a friend, and he went against his wife and all that he stood for as a lawman, quitting his job in order to pursue these guys. And then, finding out again, in the end, that ‘vengeance is mine,' says the Lord—‘and I'll take care of that.'"

I asked Lynde if his treatment of the Indian characters in the strip had resulted in any negative comment from his readers or the public in general.

"Yes," he said. "It happened during the sixties, which was an era of the strong civil rights awareness. Remember, though, that I grew up with the Crow Indians on the Crow Reservation, and I am an honorary member of the Crow Tribe. My father and grandfather were ranchers on the Crow Reservation and were well-known by the Indians who lived there.

"The Indians themselves were great fans of even the goofy Indians in the strip," he went on. "I had some very encouraging reactions. One of them told me: At least this time, we're human beings; we're not murdering savages or the stooge for some damn paleface. The Indians loved the characters—Horse's Neck, Crazy Quilt, and Moonglow—and the chief, at least, always came off from encounters with would-be exploiters very victorious.

"But then, during the late sixties," he said, "a lawyer from Beverly Hills, who claimed to be a Piute Indian, made a large fuss, including stirring people up to picket the Los Angeles Times and to call in and protest the strip, and my explanations and letters to the Times were not enough at that particular time. I think newspapers generally were concerned about questions of race at the time, but Rick had been popular with Indian readers. The Navajo Tribe voted to include it as their only syndicated feature in their own newspaper, the Navajo Times at Windowrock, Arizona. The Indians themselves were fans, as I say; and I never did have a complaint from a Native American, except this particular one, this attorney, and he managed to get the Los Angeles Times so concerned that it threatened to cancel, and I had to back off on portraying the Indians as comic figures. I don't think I ever did again after that. Although I did bring an Indian character, the deputy, Lone Star, into the strip, done in a more serious vein."

LYNDE LEFT RICK O’SHAY in 1977. The reason: not enough money. “The strip had held its initial client list very well and had made modest gains over the years,” Lynde wrote in Cartoonist Profiles, No. 42 (June1979), “but by the early 1970s, I found myself not only operating at a loss but incurring increasing debt as well.”

He negotiated with the Tribune-News Syndicate, but that failed to alleviate his difficulties. And so he left, abandoning his child after 20 years..

“That I did so with considerable reluctance is an understatement,” he wrote. “It was an extremely difficult decision and was reached only after thoroughly considering every alternative. ... Reaction to the strip in those areas in which it appeared had convinced me that there was a much larger market for it than had been tapped. I believed then, and still believe, that Rick failed to reach its potential primarily because it was not promoted and sold as well as it might have been.”

After Lynde left , the strip was continued by other hands for a brief time (Russ Heath was one of them), and Lynde, meanwhile, pursued other enterprises: he wrote a screenplay and magazine articles, painted and did illustrations, and made the rounds of speaking engagements.

“Through it all,” he wrote, “I continued to believe that a comic strip based on the American West could be successful and that I had the ability to do such a strip.”

He was also “born again.”

Lynde wrote about his rebirth in Cartoonist Profiles, No. 40 (June 1981). Until this life-changing occurrence, he said, his ego had been his guide as he “pushed on to find the American Dream and the Good Life.”

He realized he had achieved most of those things, but he also found that as time went by, he had to work harder to maintain the image—“not only my public image, but my own image of myself. I found that I didn’t dare look back over my life too closely because I didn’t like what I saw there. The failures, the excesses, the broken marriages, the people I had hurt and disappointed—these were all swept under the rug, but that old rug was getting pretty lumpy, and I knew what was under there—and I didn’t like it.”

Although he didn’t actively consider doing another comic strip, he realized, deep down, he still wanted to do one, but didn’t quite know how to get there.

“My god had failed,” he wrote, “because my god was myself—and it was the only one I’d ever really known. This self-god, the Great Ego, the Almighty Me, had led me through divorce to booze, to attempted suicide, and to most of the known sins. I still couldn’t recite the Ten Commandments, but I had broken most of them at one time or another. And I had done a pretty thorough job of breaking myself, as well.

“I realize that all this doesn’t sound like anybody’s finest hour, but it was for me. I had encountered, at age 46, a brick wall, both personally and professionally; I stopped running, surrendered, and turned to Jesus. Like all those people I used to deride, I became Born Again. And Jesus did more than change my life: he restored it. He enhanced it. And He began the process of repairing the lifetime of damage I had done to it.”

Then in the late spring of 1978, Lynde’s agent phoned him and told him that Dick Sherry, president of Field Newspaper Syndicate, had expressed an interest in Lynde’s creating a new strip.

“I called Dick,” Lynde wrote in Cartoonist Profiles, No. 42, “and he said that it was his belief that it was time for a new western strip and asked if I’d be interested in working something up. Any doubts I may have had regarding my feelings on the subject vanished with that call, and I began work almost immediately on what was to become Latigo.”

Latigo debuted June 25, 1979; it would run for four years, until May 7, 1983. During that time, Lynde remarried and found a business partner in Lynda. He liked to draw attention to the “y” that distinguished both names.

"LATIGO WAS A DIFFERENT STRIP than Rick O'Shay," Lynde once wrote. "It was designed to be an authentic, historically accurate Western that would feature a strong, capable hero in conflict with cunning and ruthless villains, but the wrong-doers would go beyond the traditional rustlers, outlaws, and badmen to the corporate greed of the nineteenth century robber barons who used such men and who answered to no law but profit."

Despite the seeming grimness of Lynde's mission for Latigo, the strip sometimes indulges a sense of humor reminiscent of his first strip. All of Latigo, which Lynde owns, has been reprinted in three volumes by Cottonwood Publishing, Inc. And two volumes of Rick O'Shay reprints have been published; Lynde hopes to reprint the entire twenty-year run of the strip.

This effort has been hampered a bit by a scarcity of material: in December 1990, just after the publication of the memoir volume, the Lynde home was burned to the ground. All Lynde's original art, proofs of his strips, not to mention the memorabilia of a lifetime— everything went up in smoke. TMS didn't have a complete set of Rick proofs either, so Lynde turned to former assistants, friends, and fans to round up complete runs of the strip for the first two books.

Working often with strips clipped from newspapers, he (and Lynda) painstakingly retouched much of the artwork. In his introductions to the volumes, Lynde is apologetic about the quality of the reprints, but he is perhaps not seeing the trees for the forest: while the art in some strips clearly suffers, the books are nonetheless the only readable archives of the feature— and many weeks of strips are in pretty good condition.

At the time we talked in 1992, Lynde was in the midst of producing the first new Rick O'Shay material in over a decade, a full-color graphic novel in two volumes called The Price of Fame. In it, Hipshot is challenged by young gunfighters who have heard of his skill and seek to gain fame for themselves by besting him in a shootout.

"Like most of my stories," Lynde said, "—from the humorous or satirical to the serious— this story came about as a result of a ‘what if' question: What would happen if—? In this case, what would happen if Hipshot became famous through the efforts of a dime novel writer and thereby attracted all these characters. In the Michael Price review of Unforgiven and his comparison to The Price of Fame, he touched on this as well. In both cases, the characters are men who are basically trying to avoid violence but are into it for different reasons. The Eastwood character goes into it for money, for the kids, first of all. Hipshot would just as soon avoid it, but he's a proud man and is stuck with it. In some ways, we're all prisoners—if not of our fame then of what we do. We create a persona, and then it's very difficult to leave. We can perhaps turn our backs on it. And Hipshot could do that, too—he could probably hide. But not very well."

I said: "And you're dealing with a larger issue, too—Hipshot's relationship to God, which is a sort of new wrinkle, at least in my experience of Westerns. And here's a man of violence who kills, admittedly only when he has to—and is a kind of stock character in many respects—but then he's got this other relationship, which brings it onto another philosophical plane maybe than the standard Western. You're doing this deliberately, I know."

"Louis L'Amour touched on this same sort of thing," Lynde said. "There are particular kinds of men in this time of history—and in other times, too—to whom killing when necessary was done without a whole lot of soul searching. One of the old timers I knew as a kid, who is somewhat of a pattern for Hipshot--the man I mention in the memoir, Bill Mills— was that kind of man. He could easily have killed another man: all he had to do was to decide that he had it coming, and he would have felt no compunction about it. For him, it would have been like killing a coyote or any other predator, with never a glance backward. And the Eastwood character in Unforgiven is something like that, too.

"Killing didn't preclude a spiritual life," Lynde went on, "and I think that this can even be seen in some of the Old Testament—and Civil War—heroes. The warrior, the military man, a man like George Patton, for example, had strong spiritual beliefs—even including reincarnation," he said with a chuckle. "So killing becomes different for such men than it is for the rest of us."

"I suppose that is true," I said. "It's the classic tension in western mythology between the individual asserting his sense of right and wrong over everyone else's sense of right and wrong. As Bill Mills might say, If the guy deserves to die, I don't mind killing him. And that's one level of the mythology, but The Price of Fame brings another dimension into it because it's not just the individual and it's not just society, there's a supreme being involved here, too."

"Exactly right," Lynde said. "But there are rules even for those to whom killing is more-or-less routine. There's a wonderful character in a book called Warlock, a Western written by Oakley Hall—a sort of Wyatt Earp prototype, and his career is town-taming. He goes to these towns and takes the job, tames the town and moves on, and it usually involves killing. He justifies this, or manages to live with the situation, by paying scrupulous attention to the Rules. The Rules are never fully defined, but he talks about them: if you did not do it right, you will have destroyed something, and you couldn't do it again. It's like the Hollywood ethic of giving the bad guy the first draw, that sort of thing. As long as you obeyed the Rules, or lived within them, you'll be all right. It's a way of making sure in your own mind that what you're doing is all right."

LYNDE MENTIONED that doing a story in comic book format is different than doing a story for strips, and I asked him to elaborate.

"Even when I was doing the strip," he said, "I loved the Sunday page. It was a place where I could really let all the stops out and do some landscape and panoramic views and good horse action and so forth. I'm a movie buff and have always been a great fan of film, and I think that sequential art is very similar to film in many ways, so I find the freedom of doing a comic book, or graphic novel—especially in color—a lot like film. You can use a whole page or a two-page spread. You can pull close-ups. It offers a lot of freedoms—especially for a Western because I can use a two-page spread just for a scenic shot if I want to."

I observed that the rhythm of the story seemed set by the page as the narrative unit just as the daily installment sets the rhythm for a continuity strip.

Lynde said: "Yes, and some people have criticized that, and I don't know if that's valid or not. The way I did the daily strip was to have some kind of conclusion, even in a continued story, so if you picked up any single daily of mine, it would have some kind of a conclusion. It was not totally dependent on having read the story from the start. So perhaps that has carried over, and maybe the end of the page has a sort of a stopping place, too."

"A punctuation mark, sort of," I said. "There are people who feel that the page unit is something that the reader should be conscious of in a graphic novel. And there are others who say that you shouldn't. So that's one of those questions on which there are two distinct and entirely contradictory views."

"I guess what happens is that we go ahead and do whatever feels right to us," Lynde said. "Hank Ketcham once pointed out that analysis was difficult for those of us who were doing the work being analyzed. And I think that's right. You can't analyze humor, for instance. We have to do this sort of thing by feel. And that's part of the excitement to me because the graphic novel is a whole new learning area. It's my old characters and stories transferred to this area that I haven't done much in, and that makes it more exciting for me."

Looking at his finished art, I observed that it seemed to me that his pencils were very tight—carefully and completely rendered.

"Yes," he said, "that's because I had a number of assistants over the years, and I found that the way to keep it looking fairly consistent was to go to very tight pencils. I was confident that I would get back about what I put down. So I began to work that way, and then, even working alone, I find that when I get to the inking, I can really go with the penciled version. Occasionally, I'll make a change—maybe even change an entire panel; but usually, I don't. Usually, what's down is there to stay."

He uses a brush only to fill in solid blacks, doing the rest of the inking with a flexible pen point. "A 291 Gillott," he said, "—it's a great one. You can get everything from a hairline to almost a quarter of an inch so it's much like a brush in application. I never felt steady enough to use a brush for this kind of work. Someone once pointed out that you can't do a lot of physical stuff like chopping wood and fighting broncs and so on and still keep your wrist in shape to use a brush for drawing."

As a young man, Lynde worked at night, he told me, but now, he tries to take evenings off, and so he gets up early in the morning and goes right to work.

The Price of Fame is colored—fully painted with airbrush—by Julia Lacquemont, a circumstance I found peculiar, particularly considering Lynde's affection for his locales and the number of stunning scenic pictures in the books. Why didn't he color his own work?

"Part of it was just the time problem," Lynde said. "It's a bit difficult to do the writing and the penciling and the inking and the color, too. With the Pardners books, I didn't have that problem because I didn't do those in color."

"I think she did just a smashing job," I said. "I love the fact that the colors are muted. I think so many graphic novel people make the mistake of thinking that the colors have to be screaming and garish or else it's not a comic book."

"Right," Lynde said. "And some of that is the influence of the superhero stuff, I suppose. But Julia is against that herself. She also has a good ranch background. Her grandparents were ranch people in Canada. She knows horses and some of the Western detail and seems to like that a lot.

"She knows western sky, too," I said, "—she does that very well."

"We work closely together on these things," Lynde said. "I send her suggestions and tell her what I'd like to see in these particular places, and she tries to give those to me."

She colored the first of the two books using artwork photocopied from the originals, Lynde explained. But the black lines didn't stand up well with her airbrush, so the second book was colored using the blueline process in which the black lines of the artwork are reproduced as non-photo blue on paper suitable for applying color. After the resulting artwork is colored and photographed for the color plates, the black lines are photographed separately for the black plate. I asked Lynde what difficulties he faced as publisher of his own material. Apart from the usual problems in preparing the work for printing and getting it well printed, there are a host of problems associated with marketing the products. Determining how many copies of a given product to print, for instance, is an elaborate guessing game in which the publisher balances the cost breaks he gets with volume printing against his estimates of future sales.

"And then finding ways to distribute is difficult as well," Lynde said. "We have a little advantage in that I'm not an unknown commodity. I have an existing following. So we have a mailing list of our own that we deal with. And we deal through the major comic book distributors—Diamond and Capital and the others—and the comic shops. We deal with bookstores where we can here in Montana and elsewhere. And we do a lot directly with the fans. We maintain a newsletter and let them know what we're up to. That's the quest. The syndicate told me I had fifteen million readers a day when I was doing the strip, so if we could just get through to a few of those readers, we'd have a successful market for the new products," he said, laughing.

Many of the Cottonwood Publishing products and the fan newsletter can be found on the Web at stanlynde.net, what’s left of a more ambitious enterprise, now somewhat shut down as Lynde concentrated on writing novels instead of drawing comic strips and graphic novels. When Lynde and I talked in 1992, he said he and Lynda intended to make a living at Cottonwood—"and we're not terribly concerned if it's not the best living in the world as long as we can do what we want to do. We have the independence and the freedom to do that—just see where it goes."

At the first of next year, 2013, it will be going to Ecuador, a country where Stan and the Lady Publisher can winter comfortably on Social Security income. They’ll return to Montana in the autumns.

Whatever happens, Lynde in 1992 was passionate about cartooning. "I just love this business," he said. "I love and believe in sequential art as a form. I think even in this day of electronics, there are still new things to be learned, and it's going to be exciting in the next few years because I think young artists are going to discover new things. Cartooning is going to be viable, I think, as long as people read."

I asked if he had any advice for young cartoonists.

"I guess if I said anything it would be to believe in yourself and continue to go for it," he said. "But you have to feel compelled to do it. Years ago, Chet Gould told me, We have been born to do this for a living--otherwise, no one could pay us enough to make it worthwhile. If you're born to do it, then you'll do it. You'll just keep going and find the ways. I guess that's what I would say: If you want to do it, believe in yourself and go for it."

And when I asked if there were any downsides in this, he laughed and said:

"I always think of Chic Young's remark that the real danger in this business is falling asleep at the drawingboard and putting your eye out with the pen."

While we still have both eyes in their sockets, here’s something to look at—a short gallery of Lynde Works.