The clouds in Paris were so low it seemed possible to reach up and wipe your palm across them. It’s a good sign, everyone was saying. If the skies are grey now, it means we’ll have a good summer. Instead, a band of bad weather stuck over northern Europe like a needle on a scratched LP, and the whole summer stayed the color of the Seine.

Perhaps the greyest part of the city that April had been a side street in the 11th arrondissement. It was as long as a tennis court, and along one side ran a simple block of a building with blank walls and municipal edges. On the other, cramped and asymmetrical shopfronts leaned on one another like people on the back seat of a bus. A sign above one of them read Art KERBLOOEY, punctuated with a cartoon explosion. The door below it was covered in decals and advertisements, clipped from newspapers. And behind that, a slightly stooped man in a blue shirt and braces wrestled with bolts and deadlocks before inviting me in. Can I get you a drink?, he asked in a creaking Texan accent. Are you sure? How about a beer?

This was Gilbert Shelton, one of the true greats of American underground comics. Back in the sixties he spliced the Three Stooges with the emerging counterculture and created The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, a perfectly funny strip that has never been out of print. Its stars are Freewheelin’ Franklin, Phineas, and Fat Freddy, three flat-sharing, patchouli-oiled poltroons whose exploits became increasingly Munchausen-esque as the series developed. In the early strips, they’d try to conceal their marijuana plants from the police. Yet by the end, they’d founded a corrupt, pseudo-mystical religion and become the richest men on the planet. At their heels for each step of this labyrinthine journey was Fat Freddy’s Cat – a sarcastic, sexually voracious feline with a Jimmy Durante nose and a habit of clawing waterbeds. In their wake came a slew of modern cartoons that aped the trio's blend of pratfalling and satire, The Simpsons included.

Gilbert’s studio was long and narrow and piled with all sorts. Across the table-tops were maps, receipts, an Oxford English Dictionary and rock and roll CD's. In one corner there was a small display cabinet full of comic books and key rings and patches for a denim jacket. By the window was a foot-long model of a Cadillac with bubble-gum pink fins. On the walls, in irregular frames, were Gilbert’s drawings. His porcine superhero, Wonder Warthog, swooshed down from the sky and stamped a car in two, a tiny cape flapping above him. The Freak Brothers relaxed by a pool on top of a skyscraper, surrounded by palm trees and tropical plants. And a Cadillac - the same as the model in the window - sailed across a foaming wave with its roof pulled back and a mast lashed to its seats.

Gilbert pointed up at it.

Gilbert Shelton: That drawing’s from one of my newer strips – Not Quite Dead – which I’ve been working on with Pic, the French cartoonist. It’s about an aging rock band.

Elliot Elam: I read the latest issue! But I struggled with the title. How do you say it? "Last gig in Shan-ga-rig"? "Shag-nar-lig"?

Heh. Most people struggle with that. It’s "Shnagrlig".

You know, when I last met you, years ago, we had the briefest of discussions …

I don’t recall the meeting. Sorry.

It was at the Institute for the Contemporary Arts. We were looking out along the Mall in London and you were impressed with the architecture. It’s something I’d always found in your comics. That, you know, the buildings and the setting are almost characters themselves, and I thought, "Oh, maybe he knows a lot about architecture." So I tracked you down and emailed you, thinking it could make an interesting piece: "An Underground Cartoonist’s take on Parisian Architecture" or something like that. And it turned out that you …

… Didn’t know too much about it at all. But I like the eccentricity you find in English architecture, and New York is good too. It has weird parts. There’s a nice book about architecture and traces of old Paris you should look at. It’s called Metronome, by a guy named Deutsch, I think. And it has pictures and also tells you where to find these traces. Old Paris isn’t very old. There are a few Roman ruins, but there’s hardly anything older than about eight hundred years.

Did you expect to find more when you moved here?

Yeah. I didn’t realize that it was a relatively new city. I’d lived in Barcelona before and Barcelona is very old.

And there’s all of that Gaudi architecture to look at.

It was interesting how he worked. He used a team of craftsmen to add the decoration to his things. He had the basic ideas and he had other people add the trim and so on. He designed the major shapes, but he just left it to the sculptors to do a lot of the detail.

Where in Barcelona did you live?

I was in La Floresta, just over the hill from Tibidabo.

And when did you move to Paris?

At the end of ‘84. Moving here was sort of an accident: We had come to France for a comic book signing tour, and while we were here our charter airline went bankrupt, stranding us.

That’s quite a reason.

Yeah. To get back, my wife and I had to buy a ticket and in those days, a round-trip was the same price as one way. So we had tickets back to Paris. We went back for a while …

Back to Barcelona?

To San Francisco. We lived in Barcelona from 80 to 81. But yeah. We went to San Francisco for a couple of months and then we came back to Paris.

So, what is it that’s kept you in Paris for so long? It seems to have been somewhere that you’ve been quite happy to settle.

Well, my wife is a literary agent, and she’s very busy here. She speaks good French and there’s a need for communication between the Anglophones and the Francophones. Communication between the two is usually very bad.

And when did you start working with Pic? When was that?

’92, I think.

And that just came out of a friendship, or a need to work?

Both. I find it difficult to do things by myself. I’m too slow. And I’m better if I have a collaborator. It makes me feel like I should show up for work. Pic has his own career of course, We’re getting ready to start a new Not Quite Dead book, but the sales on the last issue had been pretty disappointing.

It’s pronounced "peak"?

Yeah, but all the Anglophones instinctively say "pick". The short i sound is incomprehensible to the French. They think "pick" and "peak" are the same word, just like we can’t really pronounce the French r. And they can’t usually pronounce th.

How good is your French?

Oh, I can get by. I can read better than I can understand conversation. I can read all right.

I find that I can understand what the conversation might be about, but I can’t respond too well.

Sometimes I can’t even understand what it might be about. But if it’s one-on-one then I can get them to repeat and I can get by.

You mentioned in an email to me that French people wear too much black.

I know. You can’t see them at night.

You’ve not hit anyone, have you?

No. But it’s a nuisance, driving a car here. The people pay no attention to traffic lights.

What do you drive? That’s another thing that was always clear from your books – your love for cars. There’s an almost obsessive attention to detail with them. All these wonderfully rendered Citroens and, of course, Cadillacs …

I used to be an enormous fan of cars. I’m not any more because it’s so unpleasant driving in France, but they’re still in my work. We’ve got that 1959 Cadillac in the Not Quite Dead story. We had the model in the window made up for us in Japan. It makes it a lot easier to draw.

All of this stuff on the walls, it looks as though you prepared it for a show.

We had a publication party for Not Quite Dead, and a lot of this is just left over from that. But one of these days I’m going to maybe make a little art gallery out of this. That’s why I redesigned it and put in the lights and stuff like that. But I’ve never actually done anything.

Was I right in thinking that you’d written another Freak Brothers strip which never got drawn?

I’m working on one right now.

Really?

There are a couple of pages here and there, but not very much.

Gilbert told me how the new strip was set ‘in whatever city it is; the big city. Presumably San Francisco or New York or something like that’ and said that he had lived in both. As I understood it, The Freak Brothers had first appeared in The East Village Other, an underground New York newspaper that played a huge part in launching the careers of cartoonists like Robert Crumb. But Gilbert corrected me:

Not quite. There was an Austin Texas underground weekly newspaper called The Rag and they started in that. And then I moved to New York and worked for The East Village Other. Then I lived in Los Angeles and worked for the Los Angeles Free Press. And then I was in San Francisco and so on.

Do you still find that you have a real passion for it?

For comics?

Yeah. Or just for drawing.

Ah. It’s always been a hassle for me. I’m the opposite of someone like Robert Crumb. He’s a compulsive worker. I’m a compulsive shirker. I like to finish. It makes me happy to finish something.

I think I first saw your work when I was about eleven. My dad had a copy of the first Freak Brothers collection, which I’ve actually brought along with me.

In the UK, Knockabout Comics republished the Rip Off Press editions with a couple of minor changes because they couldn’t import American books. Those were banned. But if you published in England it was okay, you just couldn’t import the things.

I met Crumb once and he said the same thing had happened with his work.

One time, my British publisher brought some books over to France for the comics festival here and when he tried to take them back home he had them confiscated.

Well, here’s the copy my father had.

This is one of the early printings, but it’s not the very first one. This is the second or third, I think. Oh no, this isn’t. This is a Knockabout printing. It could be the first Knockabout edition.

I think there was a certain age where he must have felt that maybe I could look at it, and not be corrupted.

Yeah. Even little kids like Fat Freddy’s Cat. All the scatological humor. They love it when he shits on the pillow.

Is Fat Freddy’s Cat in the new strip you’re doing?

No. In this strip, Phineas becomes a suicide bomber.

Gilbert opened out a large, flat folder onto the floor in front of us. Inside were two or three comic pages, mostly drawn in light, unfinished pencil but with a few panels that had been detailed in scratchy black ink. The Freak Brothers and their apartment looked the same as they had in the mid sixties. In one panel, Franklin sat in an armchair reading a graphic novel adaptation of Lolita, credited to Alan Moore.

He’s reading an Alan Moore book.

One that doesn’t exist as far as I know. He’s good, is Moore. But when I read From Hell I was disappointed when I got to the end and found that he hadn’t done all of that research himself, he’d just taken it from pre-existing books.

It’s great reading that book and living in London, though. Because you’re full of information about the city that you can bore people to tears with.

Heh. I guess that’s true.

It’s funny how your characters age, or rather …

… They don’t. There was one little strip where they were old men, in the future, but it’s one of those comics where they stay the same.

How long does it take you to do a page?

Oh, I don’t know. Forever.

One of the things I’d heard you say is that when you moved to France, you were able to finally tell people what you did. That there was a prestige afforded to comics that you didn’t find in America.

Yes. I used to tell people that I’m in the publishing business. But here I can probably say that I’m a cartoonist, or a "dessinateur de bande dessinée."

Did they know your stuff well here?

Yeah. It’s well known. It’s been around for a while. The problem is that the French comic book industry publishes around four thousand new comic books every year. That’s more than a hundred a week. And the bookstore owners can’t cope with that. They know the Freak Brothers and they know they can sell some, so they can order that.

Who translates it?

Different people. Jean-Pierre Mercier and Liz Saum did a lot of the early ones. Nowadays the wife of the publisher does it, Christine Kaddour. She did this one. It’s a new collection.

Why did you redraw that cover?

I redrew all of them for the French editions.

Did doing that kick open any old memories?

Not really. I just wanted to improve on the early stuff. These newer ones are watercolor. We used every conceivable technique in the early editions, to get the Freak Brothers in color. The redone ones are generally better than the originals.

Gilbert handed me a thick, paperback collection of his strips. On the cover, the Freak Brothers were loping along a litter-strewn city street, holding a middle finger, a fist and a peace above their heads as the traffic buzzed behind them. The cover, Gilbert told me, had originally been drawn for High Times – a monthly magazine dedicated to the pleasures of marijuana. His work had become a regular feature in High Times by the late seventies, providing comic relief between articles by the likes of William Burroughs and Hunter S. Thompson. It was also in the late seventies that Shelton had begun collaborating with the cartoonist and fine artist Paul Mavrides. With the writer Dave Sheridan (who died of cancer in 1982), they created some of the most epic and detailed of the Freak Brothers’ adventures and worked together on the sublime Idiots Abroad, where the trio globe-trot with Scottish terrorists, a South American cult, and a mechanized chicken.

There was a wonderful strip in High Times, set in Holland, which even had you in it, along with Paul Mavrides, and you found the Freak Brothers on a houseboat in Amsterdam.

That was the last one we did. Mavrides and I were invited to be the judges for a marijuana seed grower’s contest. When we arrived in Amsterdam they gave us each thirty samples to smoke in five days. Six per day.

Wow.

By the time I’d smoked three puffs of the first one I was so stoned that I couldn’t tell the difference and I gave them all the same score. But Mavrides smoked all of the samples and wrote a lengthy critique of each one.

What’s he doing now?

Well, I hope he’s going to work on this new strip with me. He still lives in San Francisco, in a rent-controlled, cheap apartment. So he’s not that motivated to do any work.

Who knows if we can, but to get back to the architecture thing, you were saying as well that there was a building in Paris you’d like to see torn down.

The Montparnasse Tower, which is full of asbestos. They’re talking about tearing it down. That would make Paris even nicer. I like the Métro stations, too, of course.

The Hector Guimard stuff. Am I pronouncing that right?

Yeah. There are about a half dozen Hector Guimard buildings but not many.

I was reading about him. He moved to New York in the end. And I read how the press tired of him. Not of his work, exactly, but of his "personality." It seemed a very ambiguous thing to say.

I’m afraid I don’t know too much about about Guimard. I do like his work, though. My favorite building in the world, however, at least for the interior decoration, is the Municipal Building in Prague, decorated by a dozen prominent Art Deco artists. I like the Art Nouveau stuff in Brussels, too, including the building that houses the Belgian comic book museum, which is a very nice building – and a very nice museum – specializing in great Belgian cartoonists, of which there are quite a few. Europe knows how to celebrate that kind of thing.

A friend went to Hanover to see a huge retrospective on Ronald Searle. I think Searle left all of his work to the museum after his death, too. That must be quite something.

Why Germany?

I think he saw himself as a European, and felt like he could do better work there. He moved to France like you. It seems to be a theme with cartoonists. My friend got to know Searle a little bit, and now runs a blog of his work, I’ll send you the link.

I’m a big fan of Searle’s but I don’t know that much about him.

He died earlier this year. In England, I think a lot of people thought he was already dead.

Oh yeah?

Yeah, For his 90th birthday, there was some interest. There was a wonderful exhibition of his work at the Cartoon Museum in London, for example. But until then, we’d pretty much ignored him. That’s the way we do it in England. We celebrate you once you’re gone.

That could be true.

While I’m here in Paris, whose work should I look out for?

In the world of comics?

Yeah.

Here are a couple of my favorites. Fluide is maybe the best comics magazine. Fluide Glacial. The name comes from a practical joke novelty that you put on cushions and it freezes your ass. Something like that. There’s some funny stuff in it. This guy’s great – Lindingre. Frank Margerin is funny, too. Here’s a cartoon about marijuana-smoking rats. It’s well drawn, but I couldn’t tell you how funny it is. It’s a good magazine.

So you’re still very much on top of it, the comic scene.

Yes. These are my French lessons.

There seem to be a lot of Americans here, and Paris seems to be a draw for people from the States. It’s as if it’s the place where they can be artistic, and create their masterpieces.

Well, that’s the legend from the Lost Generation. Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound. Gertrude Stein. All of that.

Woody Allen seems to buy into it, too.

It’s a myth of course. There might have been some truth to it in the twenties and thirties. But I don’t know. There’s not much of an ex-pat community. The people I know here are well integrated. The American Center went bankrupt. In fact, that’s one of the architectural masterpieces that Pic wanted you to see. Do you know about it? It’s in the 12th. A couple of blocks south of here.

I’ll go see it. So, you don’t see people walking around in berets and a black turtlenecks?

If you do, you know it’s an American. Old French men still wear berets, but the French didn’t wear any sort of hats at all for a long while. Hats weren’t really in style here for a long time. They started to come back into fashion a bit. With baseball caps and that kind of thing.

Gilbert reached down under his desk, taking out a huge map of the city and rolling it out across the floor.

One thing you should see, perhaps, is the Bibliothèque Nationale. Apparently, when they built it, they didn’t know you shouldn’t have sunlight directly on the books.

So everything went brown, or bleached?

That’s right. So they had to hang shutters on all the windows.

There’s a library in South London, this huge glass structure. But people kept smashing the windows, and so they had to cover the whole thing in wire mesh.

What happened to that old generating plant?

Battersea Power Station?

Are they still going to make something out of that?

I think so, but nothing yet. You know the Pink Floyd cover?

Of course.

Well, it was the anniversary of that record being released, and so they floated this great pig over the top of the power station. I got the train into the city one morning and there was this huge pig floating about.

Ha ha.

But no, they’ve done nothing yet as far as I know. I hope they don’t just turn it into flats or stick a McDonald’s in it. I quite like the fact that it’s empty. It’s like an old ghost in the middle of the city.

There’s a place in Barcelona. This old brick amphitheater they used to use for bullfighting. And what they did with that was, they raised the whole thing up fifteen feet and put a shopping center in at ground level.

Wow.

And here’s something. You see this building across the street? This was designed by Hausmann, the redesigner of Paris. He did the Grand Boulevard, and all of that. This building isn’t anywhere near as substantial of course. In the Second World War, it’s where they shipped off the Jewish children. It’s a historical monument, but I don’t know if it’s that great a piece of architecture. I mean, it’s not a tourist area around here.

Is that why you chose to live here?

No. It was just by accident. We inherited someone’s apartment and we liked the neighborhood. It was convenient. It has the cemetery of Père Lachaise and that’s about all. That’s the only tourist thing. Place de la Bastille, maybe.

Shall we go and eat? And would you mind awfully if I took your photo, Gilbert?

Sure.

Gilbert sat back in his chair and smiled as I took a few snaps. Afterwards, we walked to Brasserie Le Rey at the end of Rue de Voltaire. "They do great salads," Gilbert said as I looked through the menu. The waiter brought a carafe of wine.

It’s strange how the French can drink wine in the afternoon and then go back to work.

Oh God, I know. I’ll be asleep later. Hey. I wondered something. Does it feel like home around here?

In Paris? Yes. In fact it’s boring.

It really is home, then.

I like to have an excuse to go tourist-ing when people come to town. When I first moved here I used to walk everywhere. But now I know the neighborhood so well, that I have to walk for an hour before I find anything interesting.

Is there much about America that you miss?

I prefer American food. This whole deal with having to eat out at restaurants the whole time - I find it tedious. And they feel sorry for you here if you eat by yourself.

I see there’s a McDonald’s next door.

It used to be a Burger King and then McDonald’s bought out Burger King in Paris. I prefer Burger King, I go there whenever I go to Amsterdam.

Apparently J.D. Salinger was a fan of Burger King too. They found a letter he wrote to a friend, and in it he recommended the Whopper.

One of the food critics for Esquire magazine said, years ago, that he liked McDonald’s. It was a scandalous moment.

So what do you have planned for later?

A friend of mine is a cartoonist, and he’s up at this cartoon art gallery up on Rue Saint-Honoré. I’m going to go to that. There’s another great gallery you should see – Galerie Martel.

I forgot to ask. Did you ever get chance to get into the catacombs?

Yes. I’ve been in the secret catacombs. There’s three hundred kilometers of them, but only maybe three or four which are open to the public. The rest of it you have to get a teenage guy to take you down there.

Didn’t the police go down there and find a fully working cinema?

That’s right. There was also a place that had been the wine cellar of a big restaurant. The catacombs were about sixty feet underground at this point and there was this long, winding staircase down to the cellar. These kids got in through the wall from the catacombs and drank up all the wine. And now the stairway back to the surface has been taken out.

I bet.

That’s one of the funnier stories.

What’s it like down there?

There’s a few puddles and stuff but it’s fairly clean. It’s sandy, but not muddy.

How long did you stay down there?

Oh, all night. Especially since while we were down there somebody blocked up the exit.

How did you get out again?

Oh, one of the guys eventually got the concrete blocks out of the exit, but it took him about two hours.

Terrifying.

Our interest was more in the old peripheral railroad tracks. There was a line that circled Paris and I think the tracks had been taken up but much of it is still there, I think.

In London there was this old, automatic and driver-less postal train that used to run between Paddington and East London somewhere. It started up in the twenties and shut down about ten years ago, but apparently all of that stuff is still there underground. All of the old boxes and signs and stuff. And all the lights still work.

Oh yeah? Can you see any of it?

Yeah. Well, if you can get down there. Some guys did just that and put their photos online. I’ll find a link about it and email it to you.

The waiter brought our food. Gilbert had chosen a piece of roasted lamb that made my dish – a salad overpopulated with boiled eggs – look bland and pathetic.

Look at that. You know, I’m getting obsessed with eggs. I seem to eat them in everything. I’ll soon be eating nothing else.

But you know if you eat nothing but boiled eggs you can starve to death. They lack essential vitamins. The same with rabbit.

All those hunters who ate nothing but rabbit and died of malnutrition.

That’s right.

Another thing I read was about food in the Franco Prussian war. A whole cat would sell for about 10 or 12 francs because Paris was surrounded and people were starving.

People would trade their pet cats with other people so they didn’t have to eat their own pet. And they ate all the animals in the zoo.

Including two of the prize elephants, right?

Yes. That’s a true story. They ate two elephants.

Afterwards, the waiter cleared away our plates and asked if we wanted coffee. I nodded, a little drunk, and turned off my tape recorder. Gilbert seemed relieved at that, and that we could be quiet for a while. Behind him, a rusty mirror reflected the all but empty restaurant while, on the street outside, people zipped back and forth and the traffic beeped. "This is a nice place," he said.

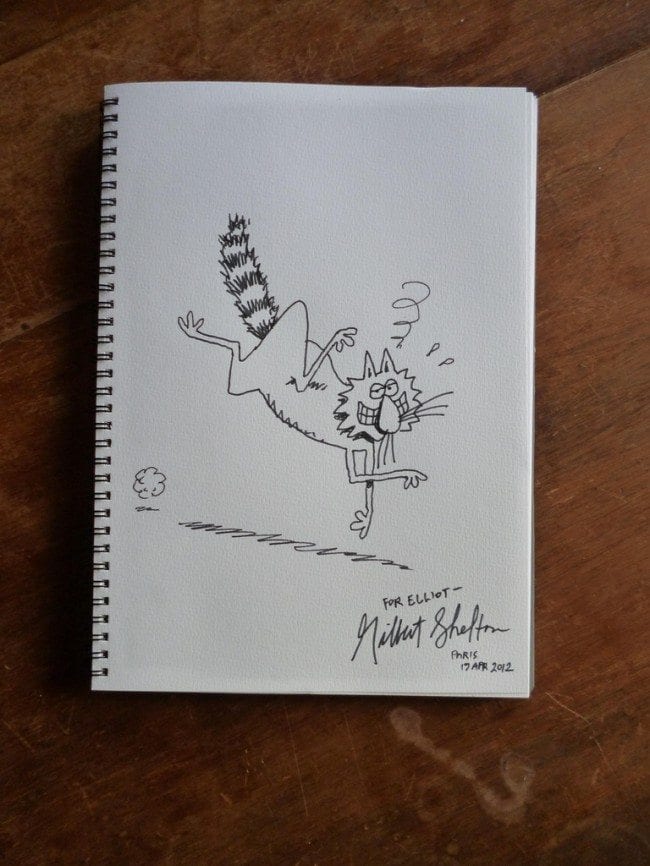

Later, back at his studio, I asked Gilbert if he would draw something in my notebook. "Sure," he said and, within a few moments, Fat Freddy’s Cat was scampering across the pages. "I’ve drawn him so many times now." Gilbert said, putting the cap back on his pen. "I could probably draw him in my sleep." The cat looked like I did after all that wine, and all that talk about secret catacombs and marijuana competitions and elephant steaks. Its eyes were lidded and dizzy, and a huge bleary grin had spread across its face.